This

section

describes

the

status

of

this

document

at

the

time

of

its

publication.

Other

documents

may

supersede

this

document.

A

list

of

current

W3C

publications

and

the

latest

revision

of

this

technical

report

can

be

found

in

the

W3C

technical

reports

index

at

http://www.w3.org/TR/.

This

is

the

9

December

2003

Last

Call

Working

10

May

2004

Editor's

Draft

of

"Architecture

of

the

World

Wide

Web,

First

Edition."

The

Last

Call

review

period

ends

5

March

2004,

at

23:59

ET.

Please

send

Last

Call

review

comments

on

this

document

before

This

draft

takes

into

account

a

few

additional

TAG

resolutions

that

date

to

were

omitted

from

the

7

May

draft;

see

the

deleted text:

public

W3C

TAG

mailing

list

public-webarch-comments@w3.org

(

archive

).

Last

Call

Working

Draft

status

is

described

in

<a href="http://www.w3.org/2003/06/Process-20030618/tr.html#last-call" shape="rect">

section

7.4.2

</a>

of

the

W3C

Process

Document.

)

.

This

document

has

been

developed

by

W3C's

Technical

Architecture

Group

(TAG)

(

charter

).

deleted text:

The

TAG

decided

unanimously

to

advance

to

Last

Call

at

their

4

Dec

2003

teleconference

(

<a href="http://www.w3.org/2003/12/04-tag-summary#lcdecision" shape="rect">

minutes

</a>

).

A

complete

list

of

changes

to

this

document

since

the

first

public

Working

Draft

is

available

on

the

Web.

The

TAG

charter

describes

a

process

for

issue

resolution

by

the

TAG.

In

accordance

with

those

provisions,

the

TAG

maintains

a

running

issues

list

.

The

First

Edition

of

"Architecture

of

the

World

Wide

Web"

does

not

address

every

issue

that

the

TAG

has

accepted

since

it

began

work

in

January

2002.

The

TAG

has

selected

a

subset

of

issues

that

the

First

Edition

does

address

to

the

satisfaction

of

the

TAG;

those

issues

are

identified

in

the

TAG's

issues

list.

The

TAG

intends

to

address

the

remaining

(and

future)

issues

after

publication

of

the

First

Edition

as

a

Recommendation.

This

document

uses

the

concepts

and

terms

regarding

URIs

as

defined

in

draft-fielding-uri-rfc2396bis-03,

preferring

them

to

those

defined

in

RFC

2396.

The

IETF

Internet

Draft

draft-fielding-uri-rfc2396bis-03

draft-fieldi

ng-uri-rfc2396bis-03

is

expected

to

obsolete

RFC

2396

,

which

is

the

current

URI

standard.

The

TAG

is

tracking

the

evolution

of

draft-fielding-uri-rfc2396bis-03.

Publication

as

a

Working

Draft

does

not

imply

endorsement

by

the

W3C

Membership.

This

is

a

draft

document

and

may

be

updated,

replaced

or

obsoleted

by

other

documents

at

any

time.

It

is

inappropriate

to

cite

this

document

as

other

than

"work

in

progress."

The

latest

information

regarding

patent

disclosures

related

to

this

document

is

available

on

the

Web.

The

World

Wide

Web

(

WWW

</acronym>,

,

or

simply

Web)

Web

)

is

an

information

space

in

which

the

items

of

interest,

referred

to

as

resources

,

are

identified

by

global

identifiers

called

Uniform

Resource

Identifiers

(

URIs

URI

).

A

travel

scenario

is

used

throughout

this

document

to

illustrate

typical

behavior

of

Web

agents

—

people

or

software

(on

behalf

of

a

person,

entity,

or

process)

acting

on

this

information

space.

Software

agents

include

servers,

proxies,

spiders,

browsers,

and

multimedia

players.

Story

While

planning

a

trip

to

Mexico,

Nadia

reads

"Oaxaca

weather

information:

'http://weather.example.com/oaxaca'"

in

a

glossy

travel

magazine.

Nadia

has

enough

experience

with

the

Web

to

recognize

that

"http://weather.example.com/oaxaca"

is

a

URI.

Given

the

context

in

which

the

URI

appears,

she

expects

that

it

allows

her

to

access

weather

information.

When

Nadia

enters

the

URI

into

her

browser:

-

The

browser

performs

an

information

retrieval

action

in

accordance

with

its

configured

behavior

for

resources

identified

via

the

"http"

URI

scheme.

-

The

authority

responsible

for

"weather.example.com"

provides

information

in

a

response

to

the

retrieval

request.

-

The

browser

displays

the

retrieved

information,

which

includes

hypertext

links

to

other

information.

Nadia

can

follow

these

hypertext

links

to

retrieve

additional

information.

This

scenario

illustrates

the

three

architectural

bases

of

the

Web

that

are

discussed

in

this

document:

-

Identification

.

Each

resource

is

identified

by

a

URI.

In

this

travel

scenario,

the

resource

is

about

a

periodically-updated

report

on

the

weather

in

Oaxaca

Oaxaca,

and

the

URI

is

"http://weather.example.com/oaxaca".

-

Interaction

.

Protocols

define

the

syntax

and

semantics

of

messages

exchanged

by

agents

over

a

network.

Web

agents

communicate

information

about

the

state

of

a

resource

through

the

exchange

of

representations

.

In

the

travel

scenario,

Nadia

(by

clicking

on

a

hypertext

link

)

tells

her

browser

to

request

a

representation

of

the

resource

identified

by

the

URI

in

the

hypertext

link.

The

browser

sends

an

HTTP

GET

request

to

the

server

at

"weather.example.com".

The

server

responds

with

a

representation

that

includes

XHTML

data

and

the

Internet

Media

Type

"application/xml+xhtml".

media

type

"application/xhtml+xml".

-

Formats

.

Representations

are

built

from

a

non-exclusive

set

of

data

formats,

used

separately

or

in

combination

(including

XHTML,

CSS,

PNG,

XLink,

RDF/XML,

SVG,

and

SMIL

animation).

In

this

scenario,

the

representation

data

format

is

XHTML.

While

interpreting

the

XHTML

representation

data,

the

browser

retrieves

and

displays

weather

maps

identified

by

URIs

within

the

XHTML.

The

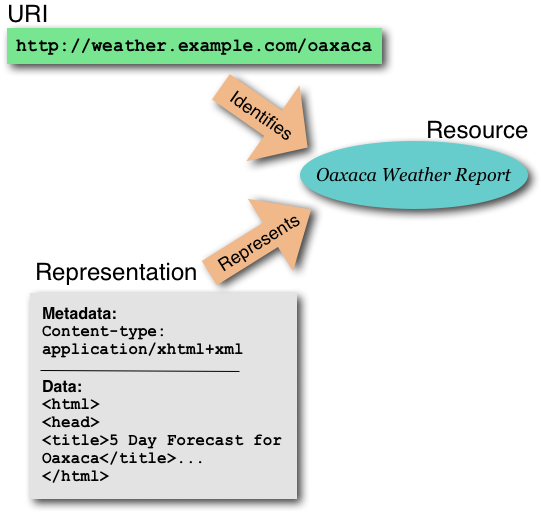

following

illustration

shows

the

relationship

between

identifier,

resource,

and

representation.

This

document

describes

the

properties

we

desire

of

the

Web

and

the

design

choices

that

have

been

made

to

achieve

them.

This

document

promotes

re-use

of

existing

standards

when

suitable,

and

gives

guidance

on

how

to

innovate

in

a

manner

consistent

with

the

Web

architecture.

The

terms

MUST,

MUST

NOT,

SHOULD,

SHOULD

NOT,

and

MAY

are

used

in

the

principles,

constraints,

and

good

practice

notes,

principles,

etc.

notes

in

accordance

with

RFC

2119

[

RFC2119

].

However,

this

document

does

not

include

conformance

provisions

for

deleted text:

at

least

these

reasons:

-

Conforming

software

is

expected

to

be

so

diverse

that

it

would

not

be

useful

to

be

able

to

refer

to

the

class

of

conforming

software

agents.

-

Some

of

the

good

practice

notes

concern

people;

specifications

generally

define

conformance

for

software,

not

people.

-

The

addition

of

a

conformance

section

is

not

likely

to

increase

the

utility

of

the

document.

This

document

is

intended

to

inform

discussions

about

issues

of

Web

architecture.

The

intended

audience

for

this

document

includes:

-

Participants

in

W3C

Activities;

i.e.,

developers

designers

of

Web

technologies

and

specifications

in

W3C

-

Other

groups

and

individuals

developing

designing

technologies

to

be

integrated

into

the

Web

-

Implementers

of

W3C

specifications

-

Web

content

authors

and

publishers

Readers

will

benefit

from

familiarity

with

the

Requests

for

Comments

(

RFC

)

series

from

the

IETF

,

some

of

which

define

pieces

of

the

architecture

discussed

in

this

document.

Note:

This

document

does

not

distinguish

in

any

formal

way

the

terms

"language"

and

"format."

Context

determines

which

term

is

used.

The

phrase

"specification

designer"

encompasses

language,

format,

and

protocol

designers.

This

document

presents

the

general

architecture

of

the

Web.

Other

groups

inside

and

outside

W3C

also

address

specialized

aspects

of

Web

architecture,

including

accessibility,

internationalization,

device

independence,

and

Web

Services.

The

section

on

Architectural

Specifications

includes

references.

This

document

strikes

a

balance

between

brevity

and

precision

while

including

illustrative

examples.

TAG

findings

are

informational

documents

that

complement

the

current

document

by

providing

more

detail

about

selected

topics.

This

document

includes

some

important

material

excerpts

from

the

findings.

Since

the

findings

evolve

independently,

this

document

also

includes

references

to

approved

TAG

findings.

For

other

TAG

issues

covered

by

this

document

but

without

an

approved

finding,

references

are

to

entries

in

the

TAG

issues

list

.

Many

of

the

examples

in

this

document

involve

human

activity

suppose

the

familiar

Web

interaction

model

where

a

person

follows

a

link

via

a

user

agent,

the

user

agent

retrieves

and

presents

data,

the

user

follows

another

link,

etc.

This

document

does

not

discuss

in

any

detail

other

interaction

models

such

as

voice

browsing.

For

instance,

when

a

graphical

user

agent

running

on

a

laptop

computer

or

hand-held

device

encounters

an

error,

the

user

agent

can

report

errors

directly

to

the

user

through

visual

and

audio

cues,

and

present

the

user

with

options

for

resolving

the

errors.

On

the

other

hand,

when

someone

is

browsing

the

Web

through

voice

input

and

audio-only

output,

stopping

the

dialog

to

wait

for

user

input

may

reduce

usability

since

it

is

so

easy

to

"lose

one's

place"

when

browsing

with

only

audio-output.

This

document

does

not

discuss

how

the

principles,

constraints,

and

good

practices

identified

here

apply

in

all

interaction

contexts.

The

important

points

of

this

document

are

categorized

as

follows:

-

<a name="cat-constraint" id="cat-constraint" shape="rect">

Constraint

Principle

-

An

architectural

constraint

principle

is

a

restriction

in

behavior

or

interaction

within

the

system.

Constraints

may

be

imposed

for

technical,

policy,

or

other

reasons.

</dd>

<dt>

<a name="cat-design" id="cat-design" shape="rect">

Design

Choice

</a>

</dt>

<dd>

In

the

design

of

the

Web,

some

design

choices,

like

the

names

fundamental

rule

that

applies

to

a

large

number

of

the

<p>

situations

and

<li>

variables.

Architectural

principles

include

"separation

of

concerns",

"generic

interface",

"self-descriptive

syntax,"

"visible

semantics,"

"network

effect"

(Metcalfe's

Law),

and

Amdahl's

Law:

"The

speed

of

a

system

is

limited

by

its

slowest

component."

-

Constraint

-

In

the

design

of

the

Web,

some

design

choices,

like

the

names

of

the

p

and

li

elements

in

HTML,

or

the

choice

of

the

colon

(:)

character

in

URIs,

are

somewhat

arbitrary;

if

deleted text:

<par>,

<elt>,

or

*

paragraph

had

been

chosen

instead,

instead

of

p

or

asterisk

(*)

instead

of

colon,

the

large-scale

result

would,

most

likely,

have

been

the

same.

Other

design

choices

are

more

fundamental;

these

are

the

focus

of

this

document.

Design

choices

can

lead

to

constraints,

i.e.,

restrictions

in

behavior

or

interaction

within

the

system.

Constraints

may

be

imposed

for

technical,

policy,

or

other

reasons

to

achieve

certain

properties

of

the

system,

such

as

accessibility

and

global

scope,

and

non-functional

properties,

such

as

relative

ease

of

evolution,

re-usability

of

components,

efficiency,

and

dynamic

extensibility.

-

Good

practice

-

Good

practice

—

by

software

developers,

content

authors,

site

managers,

users,

and

specification

writers

designers

—

increases

the

value

of

the

Web.

deleted text:

<dt>

<a name="cat-principle" id="cat-principle" shape="rect">

Principle

</a>

</dt>

<dd>

An

architectural

principle

is

a

fundamental

rule

that

applies

to

a

large

number

of

situations

and

variables.

Architectural

principles

include

"separation

of

concerns",

"generic

interface",

"self-descriptive

syntax,"

"visible

semantics,"

"network

effect"

(Metcalfe's

Law),

and

Amdahl's

Law:

"The

speed

of

a

system

is

determined

by

its

slowest

component."

</dd>

<dt>

<a name="cat-property" id="cat-property" shape="rect">

Property

</a>

</dt>

<dd>

Architectural

properties

include

both

the

functional

properties

achieved

by

the

system,

such

as

accessibility

and

global

scope,

and

non-functional

properties,

such

as

relative

ease

of

evolution,

re-usability

of

components,

efficiency,

and

dynamic

extensibility.

</dd>

This

categorization

is

derived

from

Roy

Fielding's

work

on

"Representational

State

Transfer"

[

REST

].

deleted text:

Authors

of

protocol

specifications

in

particular

should

invest

time

in

understanding

the

REST

model

and

consider

the

role

to

which

of

its

principles

could

guide

their

design:

statelessness,

clear

assignment

of

roles

to

parties,

uniform

address

space,

and

a

limited,

uniform

set

of

verbs.

A

number

of

general

architecture

principles

apply

to

deleted text:

across

all

three

bases

of

Web

architecture.

1.2.1.

<a id="orthogonal-specs" name="orthogonal-specs" shape="rect">

Orthogonal

Independent

Specifications

Identification,

interaction,

and

representation

are

orthogonal

independent

(or,

"independent",

"orthogonal",

or

"loosely

coupled")

concepts:

an

identifier

can

be

assigned

-

one

identifies

a

resource

with

a

URI.

One

may

publish

and

use

a

URI

without

knowing

what

building

any

representations

are

available,

agents

can

interact

with

of

the

resource

or

determining

whether

any

deleted text:

identifier,

and

representations

can

are

available.

-

a

generic

URI

syntax

allows

agents

to

function

in

many

cases

without

knowing

specifics

of

URI

schemes.

-

in

many

cases

one

may

change

the

representation

of

a

resource

without

regard

disrupting

references

to

the

identifiers

or

interactions

that

may

dereference

them.

</p>

resource.

Orthogonality

in

Independence

of

specifications

facilitates

a

flexible

design

that

can

evolve

over

time.

The

fact,

for

For

example,

that

the

one

may

refer

to

an

image

can

be

identified

using

with

a

URI

without

needing

any

information

worrying

about

the

representation

format

chosen

to

represent

the

image.

This

independence

has

allowed

the

introduction

of

deleted text:

that

image

allowed

formats

such

as

PNG

and

SVG

without

disrupting

references

to

deleted text:

evolve

independent

of

the

specifications

that

define

image

elements.

resources.

Orthogonal

Independent

abstractions

deserve

orthogonal

benefit

from

independent

specifications.

Specifications

should

clearly

indicate

those

features

that

simultaneously

access

information

from

otherwise

orthogonal

independent

abstractions.

For

example

a

specification

should

draw

attention

to

a

feature

that

requires

information

from

both

the

header

and

the

body

of

a

message.

Although

the

HTTP,

HTML,

and

URI

specifications

are

orthogonal

independent

for

the

most

part,

they

are

not

completely

orthogonal.

independent.

Experience

demonstrates

that

where

they

are

not

orthogonal,

not,

problems

have

arisen:

-

The

HTML

specification

includes

a

protocol

extension

of

sorts:

it

specifies

how

a

user

agent

sends

HTML

form

data

to

a

server

(as

a

URI

query

string).

The

design

works

reasonably

well,

although

there

are

limitations

related

to

internationalization

(see

the

TAG

finding

"

URIs,

Addressability,

and

the

use

of

HTTP

GET

and

POST

"

)

and

the

query

string

design

impinges

on

the

server

design.

Developers

Software

developers

(for

example,

of

[

CGI

]

applications)

might

have

an

easier

time

finding

the

specification

if

it

were

published

separately

and

then

cited

from

the

HTTP,

URI,

and

HTML

specifications.

-

The

HTML

specification

allows

content

providers

to

instruct

HTTP

servers

to

build

response

headers

from

META

element

instances.

This

is

an

abstraction

violation;

the

software

developer

community

deserves

to

be

would

benefit

from

being

able

to

find

all

HTTP

headers

from

the

HTTP

specification

(including

any

associated

extension

registries

and

specification

updates

per

IETF

process).

Perhaps

as

a

result,

this

feature

of

the

HTML

specification

is

not

widely

deployed.

Furthermore,

this

design

has

led

to

confusion

in

user

agent

development.

The

HTML

specification

states

that

META

in

conjunction

with

http-equiv

is

intended

for

HTTP

servers,

but

many

HTML

user

agents

interpret

http-equiv='refresh'

as

a

client-side

instruction.

-

Some

content

authors

use

the

META

/

http-equiv

approach

to

declare

the

character

encoding

scheme

of

an

HTML

document.

By

design,

this

is

a

hint

that

an

HTTP

server

should

emit

a

corresponding

"Content-Type"

header

field.

In

practice,

the

use

of

the

hint

in

servers

is

not

widely

deployed.

Furthermore,

many

user

agents

use

this

information

to

override

the

"Content-Type"

header

sent

by

the

server.

This

works

against

the

principle

of

authoritative

representation

metadata

.

The

information

in

the

Web

and

the

technologies

used

to

represent

that

information

change

over

time.

Some

examples

of

successful

technologies

designed

to

allow

change

while

minimizing

disruption

include:

-

the

fact

that

URI

schemes

are

independently

specified,

specified;

-

the

use

of

an

open

set

of

Internet

media

types

in

mail

and

HTTP

to

specify

document

interpretation,

interpretation;

-

the

separation

of

the

generic

XML

grammar

and

the

open

set

of

XML

namespaces

for

element

and

attribute

names,

names;

-

Extensibility

extensibility

models

in

Cascading

Style

Sheets

(CSS),

XSLT

1.0,

and

SOAP

SOAP;

-

user

agent

plug-ins

plug-ins.

The

following

applies

to

languages,

in

particular

Below

we

discuss

the

specifications

property

of

"extensibility,"

exhibited

by

URIs

and

some

data

formats,

of

and

message

formats,

deleted text:

and

URIs.

<strong>

Note:

</strong>

This

document

does

not

distinguish

in

any

formal

way

the

terms

"format"

and

"language."

Context

has

determined

which

term

is

used.

promotes

technology

evolution

and

interoperability.

Language

subset

:

one

language

is

a

subset

(or,

"profile")

of

a

second

language

if

any

document

in

the

first

language

is

also

a

valid

document

in

the

second

language

and

has

the

same

interpretation

in

the

second

language.

Language

extension

:

one

language

is

an

extension

of

a

second

language

if

the

second

is

a

language

subset

of

the

first

(thus,

the

extension

is

a

superset).

Clearly,

creating

an

deleted text:

extension

language

extension

is

better

for

interoperability

than

creating

an

incompatible

language.

Ideally,

many

instances

of

a

superset

language

can

be

safely

and

usefully

processed

as

though

they

were

in

the

subset

language.

language

subset.

Languages

that

exhibit

this

property

are

said

to

be

"extensible."

Language

designers

can

facilitate

extensibility

by

defining

how

implementations

must

handle

unknown

extensions

--

for

example,

that

they

be

ignored

(in

some

way)

or

should

be

considered

errors.

For

example,

from

early

on

in

the

Web,

HTML

agents

followed

the

convention

of

ignoring

unknown

elements.

This

choice

left

room

for

innovation

(i.e.,

non-standard

elements)

and

encouraged

the

deployment

of

HTML.

However,

interoperability

problems

arose

as

well.

In

this

type

of

environment,

there

is

an

inevitable

tension

between

interoperability

in

the

short

term

and

the

desire

for

extensibility.

Experience

shows

that

designs

that

strike

the

right

balance

between

allowing

change

and

preserving

interoperability

are

more

likely

to

thrive

and

are

less

likely

to

disrupt

the

Web

community.

<a href="#orthogonal-specs" shape="rect">

Orthogonal

Independent

specifications

help

reduce

the

risk

of

disruption.

For

further

discussion,

see

the

section

on

versioning

and

extensibility

.

See

also

TAG

issue

xmlProfiles-29

.

Errors

occur

in

networked

information

systems.

The

manner

in

which

they

are

dealt

with

depends

on

application

context.

A

user

agent

acts

on

behalf

of

the

user

and

therefore

is

expected

to

help

the

user

understand

the

nature

of

errors,

and

possibly

overcome

them.

User

agents

that

correct

errors

without

the

consent

of

the

user

are

not

acting

on

the

user's

behalf.

Principle:

Error

recovery

Silent

Agent

recovery

from

error

without

user

consent

is

harmful.

Consent

does

not

necessarily

imply

that

the

receiving

agent

must

interrupt

the

user

and

require

selection

of

one

option

or

another.

The

user

may

indicate

through

pre-selected

configuration

options,

modes,

or

selectable

user

interface

toggles,

with

appropriate

reporting

to

the

user

when

the

agent

detects

an

error.

To

promote

interoperability,

specifications

specification

designers

should

set

expectations

about

behavior

in

the

face

of

known

error

conditions.

Experience

has

led

to

the

following

observations

about

error-handling

approaches.

-

Protocol

designers

should

provide

enough

information

about

the

error

condition

so

that

deleted text:

a

an

agent

can

address

the

error

condition.

For

instance,

an

HTTP

404

message

("resource

not

found")

is

useful

because

it

allows

user

agents

to

present

relevant

information

to

users,

enabling

them

to

contact

the

author

representation

provider

in

case

of

the

representation

that

included

the

(broken)

link.

</li>

<li>

Experience

with

problems.

-

Experience

with

the

cost

of

building

a

user

agent

to

handle

the

diverse

forms

of

ill-formed

HTML

content

convinced

the

authors

designers

of

the

XML

specification

to

require

that

agents

fail

deleted text:

deterministically

upon

encountering

ill-formed

content.

Because

users

are

unlikely

to

tolerate

such

failures,

this

design

choice

has

pressured

all

parties

into

respecting

XML's

constraints,

to

the

benefit

of

all.

-

An

agent

that

encounters

unrecognized

content

may

handle

it

in

a

number

of

ways,

including

as

an

error;

see

also

the

section

on

extensibility

and

versioning

.

-

Error

behavior

that

is

appropriate

for

a

person

may

not

be

appropriate

for

software.

People

are

capable

of

exercising

judgement

in

ways

that

software

applications

generally

cannot.

An

informal

error

response

may

suffice

for

a

person

but

not

for

a

processor.

See

the

TAG

issues

contentTypeOverride-24

and

errorHandling-20

.

The

Web

follows

Internet

tradition

in

that

its

important

interfaces

are

defined

in

terms

of

protocols,

by

specifying

the

syntax,

semantics,

and

sequence

of

the

messages

interchanged.

The

technology

shared

among

Web

agents

lasts

longer

than

the

agents

themselves.

It

is

common

for

programmers

working

with

the

Web

to

write

code

that

generates

and

parses

these

messages

directly.

It

is

less

common,

but

not

unusual,

for

end

users

to

have

direct

exposure

to

these

messages.

This

leads

It

is

often

desirable

to

the

well-known

"view

source"

effect,

whereby

provide

users

with

access

to

format

and

protocol

details:

allowing

them

to

"

view

source

,"

whereby

they

may

gain

expertise

in

the

workings

of

the

deleted text:

systems

by

direct

exposure

to

the

underlying

protocols.

system.

Parties

who

wish

to

communicate

effectively

must

agree

(to

a

reasonable

extent)

upon

a

shared

set

of

identifiers

and

on

their

meanings.

The

ability

to

use

common

identifiers

across

communities

motivates

global

identifiers

in

Web

architecture.

Thus,

Uniform

Resource

Identifiers

([

URI

],

currently

being

revised)

which

are

global

identifiers

in

the

context

of

the

Web,

are

central

to

Web

architecture.

Constraint:

Identify

with

URIs

The

identification

mechanism

for

the

Web

is

the

URI.

A

URI

must

be

assigned

to

a

resource

in

order

for

agents

to

be

able

to

refer

to

the

resource.

It

follows

that

a

resource

should

be

assigned

a

URI

if

a

third

party

might

reasonably

want

to

link

to

it,

make

or

refute

assertions

about

it,

retrieve

or

cache

a

representation

of

it,

include

all

or

part

of

it

by

reference

into

another

representation,

annotate

it,

or

perform

other

operations

on

it.

</p>

<p>

When

a

<a href="#def-representation" shape="rect">

representation

</a>

uses

a

URI

(instead

Formats

that

allow

content

authors

to

use

URIs

instead

of

deleted text:

a

local

identifier)

as

an

identifier,

then

it

gains

great

power

from

the

vastness

of

the

choice

of

resources

to

which

it

can

refer.

The

phrase

identifiers

foster

the

"network

effect"

describes

the

fact

that

effect":

the

usefulness

value

of

the

technology

is

dependent

on

these

formats

grows

with

the

size

of

the

deployed

Web.

Resources

exist

before

URIs;

a

resource

may

be

identified

by

zero

URIs.

However,

there

are

many

benefits

to

assigning

a

URI

to

a

resource,

including

linking,

bookmarking,

caching,

and

indexing

by

search

engines.

Designers

Software

developers

should

expect

that

it

will

prove

useful

to

be

able

to

share

a

URI

across

applications,

even

if

that

utility

is

not

initially

evident.

The

scope

of

a

URI

is

global;

the

resource

identified

by

a

URI

does

not

depend

on

the

context

in

which

the

URI

appears

(see

also

the

section

about

URIs

in

other

roles

).

Of

course,

what

an

agent

does

with

a

URI

may

vary.

The

TAG

finding

"

URIs,

Addressability,

and

the

use

of

HTTP

GET

and

POST

"

discusses

additional

benefits

and

considerations

of

URI

addressability.

Principle:

URI

assignment

A

resource

owner

SHOULD

One

should

assign

a

URI

to

each

resource

anything

that

others

will

expect

to

refer

to.

This

principle

dates

back

at

least

as

far

as

Douglas

Engelbart's

seminal

work

on

open

hypertext

systems;

see

section

Every

Object

Addressable

in

[

Eng90

].

The

most

straightforward

way

of

establishing

that

two

parties

are

referring

to

the

same

resource

is

to

compare,

character-by-character,

the

URIs

they

are

using.

Two

URIs

that

are

identical

(character

for

character)

refer

to

the

same

resource.

However,

Web

architecture

allows

resource

owners

people

to

assign

more

than

one

URI

to

a

resource.

Constraint:

<a name="design-mult-URI" id="design-mult-URI" shape="rect">

URI

uniqueness

multiplicity

Web

architecture

does

not

constrain

a

deleted text:

Web

resource

to

be

identified

by

a

single

URI.

Thus,

Consequently,

two

URIs

that

are

not

identical

(character

for

character)

can

still

refer

to

the

same

resource

(i.e.,

they

do

not

necessarily

refer

to

different

resources.

The

most

straightforward

way

resources).

To

reduce

the

risk

of

establishing

a

false

negative

comparison

(i.e.,

an

incorrect

conclusion

that

two

parties

are

referring

URIs

do

not

refer

to

the

same

Web

resource

resource)

or

a

false

positive

comparison

(i.e.,

an

incorrect

conclusion

that

two

URIs

do

refer

to

the

same

resource),

certain

specifications

license

applications

to

apply

tests

in

addition

to

character-by-character

comparison.

For

example,

for

"http"

URIs,

the

authority

component

(the

part

after

"//"

and

before

the

next

"/")

is

defined

to

compare,

as

character

strings,

be

case-insensitive.

Thus,

the

URIs

they

are

using.

"http"

URI

equivalence

is

discussed

specification

licenses

applications

to

conclude

that

authority

components

in

section

6

of

[

two

"http"

URIs

are

equivalent

when

those

strings

are

character-by-character

equivalent

or

differ

only

by

case.

By

following

the

"http"

URI

specification,

agents

are

licensed

to

conclude

that

"http://Weather.Example.Com/Oaxaca"

and

"http://weather.example.com/Oaxaca"

identify

the

same

resource.

Agents

that

reach

conclusions

based

on

comparisons

that

are

not

licensed

by

relevant

specifications

take

responsibility

for

any

problems

that

result.

Agents

should

not

assume,

for

example,

that

"http://weather.example.com/Oaxaca"

and

"http://weather.example.com/OAXACA"

identify

the

same

resource,

since

none

of

the

specifications

involved

states

that

the

path

component

of

an

"http"

URI

is

case-insensitive.

Section

6

[

URI

]

provides

more

information

about

comparing

URIs

and

reducing

the

risk

of

false

negatives

and

positives.

See

the

section

below

on

approaches

other

than

string

comparison

that

allow

different

parties

to

assert

that

two

URIs

identify

the

same

resource

.

<div class="boxedtext">

<p>

<span class="practicelab">

Good

practice:

2.1.1.

URI

aliases

Aliases

</span>

</p>

<p class="practice">

Resource

owners

should

not

create

arbitrarily

different

There

are

many

benefits

to

ensuring

that

software

can

determine,

by

following

specifications,

that

two

URIs

for

refer

to

the

same

resource.

deleted text:

</p>

</div>

<p>

URI

producers

should

be

conservative

about

the

number

of

different

URIs

they

produce

for

the

same

resource.

resource,

especially

when

software

cannot

determine

the

equivalence

of

those

URIs.

For

example,

the

parties

responsible

for

weather.example.com

should

not

use

both

"http://weather.example.com/Oaxaca"

and

"http://weather.example.com/oaxaca"

to

refer

to

the

same

resource;

agents

software

will

not

detect

the

equivalence

relationship

by

following

specifications.

On

Good

practice:

Avoiding

URI

aliases

A

URI

owner

should

not

create

arbitrarily

different

URIs

for

the

other

hand,

there

may

same

resource.

There

may,

of

course,

be

good

reasons

for

creating

similar-looking

URIs.

For

instance,

one

might

reasonably

create

URIs

that

begin

with

"http://www.example.com/tempo"

and

"http://www.example.com/tiempo"

to

provide

access

to

resources

by

users

who

speak

Italian

and

Spanish.

Likewise,

URI

consumers

should

ensure

URI

consistency.

For

instance,

when

transcribing

a

URI,

agents

should

not

gratuitously

escape

characters.

The

term

"character"

refers

to

URI

characters

as

defined

in

section

2

of

[

URI

].

Good

practice:

Consistent

URI

usage

If

a

URI

has

been

assigned

to

a

resource,

agents

SHOULD

refer

to

the

resource

using

the

same

URI,

character

for

character.

Applications

may

apply

rules

beyond

basic

string

comparison

that

are

licensed

by

specifications

When

a

URI

alias

does

become

common

currency,

the

URI

owner

should

use

protocol

techniques

such

as

server-side

redirects

to

reduce

connect

the

risk

of

false

negatives

and

positives.

For

example,

for

"http"

URIs,

the

authority

component

is

case-insensitive.

Agents

that

reach

conclusions

based

on

comparisons

that

are

not

licensed

by

relevant

specifications

take

responsibility

for

any

problems

that

result.

Agents

should

not

assume,

for

example,

that

"http://weather.example.com/Oaxaca"

and

"http://weather.example.com/oaxaca"

identify

the

same

resource,

since

none

of

the

specifications

involved

states

that

two

resources.

The

community

benefits

when

the

deleted text:

path

part

of

an

"http"

URI

is

case-insensitive.

</p>

<p>

See

section

6

[

<a href="#URI" shape="rect">

URI

</a>

]

for

more

information

about

comparing

URIs

and

reducing

owner

supports

both

the

risk

of

false

negatives

"unofficial"

URI

and

deleted text:

positives.

See

the

section

on

future

directions

for

approaches

other

than

string

comparison

that

may

allow

different

parties

to

<a href="#future-comparison" shape="rect">

assert

that

two

URIs

identify

the

same

resource

</a>.

alias.

2.2.

<a name="uri-ownership" id="uri-ownership" shape="rect">

URI

Ownership

Overloading

The

requirement

for

URIs

to

be

<a href="#URI-ambiguity" shape="rect">

unambiguous

</a>

demands

that

At

times,

different

agents

do

not

assign

intentionally

or

unintentionally

use

the

same

URI

to

identify

different

resources.

<a href="#URI-scheme" shape="rect">

URI

scheme

overloading

specifications

assure

this

using

a

variety

of

techniques,

including:

</p>

<ul>

<li>

Hierarchical

delegation

of

authority.

This

approach,

exemplified

by

refers

to

the

"http"

and

"mailto"

schemes,

allows

use,

in

the

assignment

context

of

a

part

Web

protocols

and

formats,

of

one

URI

deleted text:

space

to

refer

to

more

than

one

party,

reassignment

of

resource.

Just

as

promoting

a

piece

of

that

space

to

another,

and

so

forth.

</li>

<li>

Random

numbers.

The

generation

of

shared

vocabulary

has

tangible

value,

overloading

often

imposes

a

fairly

large

random

number,

used

cost

in

the

"uuid"

scheme,

reduces

the

risk

of

ambiguity

to

a

calculated

small

risk.

</li>

<li>

Checksums.

The

generation

of

communication.

Suppose

that

one

organization

uses

a

URI

deleted text:

as

a

checksum

based

on

a

data

object

has

similar

properties

their

site

to

refer

to

the

random

number

approach.

This

is

the

approach

taken

by

the

"md5"

scheme.

</li>

<li>

Combination

of

approaches.

The

"mid"

movie

"The

Sting",

and

"cid"

schemes

combine

some

of

the

above

approaches.

</li>

</ul>

<p>

The

approach

taken

for

another

organization

uses

the

"http"

same

URI

scheme

follows

the

pattern

whereby

to

refer

to

a

resource

that

talks

about

"The

Sting."

Inconsistent

use

of

the

Internet

community

delegates

authority,

via

URI

creates

confusion

about

what

the

deleted text:

IANA

URI

scheme

registry

[

<a href="#IANASchemes" shape="rect">

IANASchemes

</a>

]

and

identifies.

In

many

contexts,

inconsistent

use

may

not

lead

to

error

or

cause

harm.

However,

in

some

contexts

such

as

the

DNS,

over

a

set

Semantic

Web,

software

relies

on

consistent

use

of

URIs

with

a

common

prefix

to

URIs.

If

one

particular

owner.

One

consequence

of

this

approach

is

wanted

to

talk

about

the

Web's

heavy

reliance

on

creation

date

of

the

central

DNS

registry.

</p>

<p>

Whatever

resource

identified

by

the

techniques

used,

except

URI,

for

instance,

it

would

not

be

clear

whether

this

meant

"when

the

checksum

case,

movie

created"

or

"when

the

agent

has

a

unique

relationship

with

resource

about

the

URI,

called

<a name="def-uri-ownership" id="def-uri-ownership">

movie

was

created."

<dfn>

Good

practice:

Avoiding

URI

ownership

</dfn>

Overloading

</a>.

The

phrase

"authority

responsible

for

a

URI"

is

synonymous

with

"URI

owner"

in

this

document.

Avoid

URI

overloading.

The

social

implications

of

URI

ownership

are

not

discussed

here.

However,

the

success

or

failure

of

these

different

approaches

depends

on

the

extent

to

which

there

is

consensus

in

the

Internet

community

section

below

on

abiding

by

the

defining

specifications.

The

concept

of

URI

ownership

is

especially

visible

in

the

case

of

the

HTTP

protocol,

which

enables

examines

approaches

for

establishing

the

deleted text:

URI

owner

to

serve

<a href="#authoritative-metadata" shape="rect">

authoritative

representations

</a>

source

of

information

about

what

resource

a

deleted text:

resource.

In

this

case,

the

HTTP

origin

server

(defined

in

[

<a href="#RFC2616" shape="rect">

RFC2616

</a>

])

is

the

agent

acting

on

behalf

of

the

URI

owner.

</p>

</div>

<div class="section">

<h3>

2.3.

<a name="URI-ambiguity" id="URI-ambiguity" shape="rect">

URI

Ambiguity

</a>

</h3>

<p>

Just

as

a

shared

vocabulary

has

tangible

value,

the

ambiguous

use

of

terms

imposes

a

cost

in

communication.

<a name="def-uri-ambiguity" id="def-uri-ambiguity">

<dfn>

URI

ambiguity

</dfn>

</a>

refers

to

the

use

of

the

same

URI

to

refer

to

more

than

one

distinct

resource.

</p>

<div class="boxedtext">

<p>

<span class="practicelab">

Good

practice:

<a name="pr-uri-ambiguity" id="pr-uri-ambiguity" shape="rect">

URI

ambiguity

</a>

</span>

</p>

<p class="practice">

Avoid

URI

ambiguity.

</p>

</div>

<p>

URI

ambiguity

should

not

be

confused

with

ambiguity

in

natural

language.

The

English

statement

"'http://www.example.com/moby'

identifies

'Moby

Dick'"

is

ambiguous

because

one

could

understand

the

phrase

"Moby

Dick"

to

refer

to

distinct

resources:

a

particular

printing

of

this

work,

or

the

work

itself

in

an

abstract

sense,

or

the

fictional

white

whale,

or

a

particular

copy

of

the

book

on

the

shelves

of

a

library

(via

the

Web

interface

of

the

library's

online

catalog),

or

the

record

in

the

library's

electronic

catalog

which

contains

the

metadata

about

the

work,

or

the

<a href="http://ibiblio.org/gutenberg/etext01/moby10b.txt" shape="rect">

Gutenberg

project's

online

version

</a>.

identifies.

In

Web

architecture,

URIs

identify

resources.

Outside

the

bounds

context

of

Web

architecture

specifications,

URIs

can

be

useful

for

other

purposes,

for

example,

as

database

keys.

For

instance,

the

organizers

of

a

conference

might

use

"mailto:nadia@example.com"

to

refer

to

Nadia.

While

this

usage

is

not

licensed

by

Web

architecture

specifications,

in

the

context

of

the

conference,

all

parties

may

agree

to

that

local

policy

and

understand

one

another.

Certain

properties

of

URIs,

such

as

their

potential

for

global

uniqueness,

make

them

appealing

as

general-purpose

identifiers.

In

the

Web

architecture,

"mailto:nadia@example.com"

identifies

an

Internet

mailbox;

that

is

what

is

licensed

by

the

"mailto"

URI

scheme

specification.

The

fact

that

the

URI

serves

other

purposes

in

non-Web

contexts

does

not

lead

to

URI

ambiguity.

overloading.

URI

ambiguity

overloading

arises

when

a

URI

is

used

to

identify

two

different

<em>

resources

within

the

context

of

Web

</em>

resources.

protocols

and

formats.

2.4.

<a name="URI-scheme" id="URI-scheme" shape="rect">

2.3.

URI

Schemes

Ownership

In

The

requirement

that

URIs

not

be

overloaded

(explained

below)

demands

that

different

agents

do

not

assign

the

same

URI

"http://weather.example.com/",

to

different

resources.

URI

scheme

specifications

assure

this

using

a

variety

of

techniques,

including:

-

Hierarchical

delegation

of

authority.

This

approach,

exemplified

by

the

"http"

that

appears

before

and

"mailto"

schemes,

allows

the

colon

(":")

names

assignment

of

a

part

of

URI

scheme.

Each

URI

scheme

has

space

to

one

party,

reassignment

of

a

normative

specification

that

explains

how

identifiers

are

assigned

within

that

scheme.

The

URI

syntax

is

thus

a

federated

and

extensible

naming

mechanism

wherein

each

scheme's

specification

may

further

restrict

the

syntax

and

semantics

piece

of

deleted text:

identifiers

within

that

scheme.

</p>

<p>

Examples

of

URIs

from

various

schemes

include:

</p>

<ul>

<li>

mailto:joe@example.org

</li>

<li>

ftp://example.org/aDirectory/aFile

</li>

<li>

news:comp.infosystems.www

</li>

<li>

tel:+1-816-555-1212

</li>

<li>

ldap://ldap.example.org/c=GB?objectClass?one

space

to

another,

and

so

forth.

-

urn:oasis:names:tc:entity:xmlns:xml:catalog

</li>

</ul>

<p>

While

the

Web

architecture

allows

the

definition

Large

numbers.

The

generation

of

deleted text:

new

schemes,

introducing

a

new

scheme

is

costly.

Many

aspects

fairly

large

random

number

or

a

checksum

reduces

the

risk

of

URI

processing

are

scheme-dependent,

and

overloading

to

a

significant

amount

calculated

small

risk.

A

draft

"uuid"

scheme

adopted

this

approach;

one

could

also

imagine

a

scheme

based

on

md5

checksums.

-

Combination

of

deployed

software

already

processes

URIs

approaches.

The

"mid"

and

"cid"

schemes

combine

some

of

well-known

schemes.

Introducing

a

new

the

above

approaches.

The

approach

taken

for

the

"http"

URI

scheme

requires

follows

the

development

and

deployment

not

only

of

client

software

to

handle

pattern

whereby

the

scheme,

but

also

of

ancillary

agents

such

as

gateways,

proxies,

and

caches.

See

Internet

community

delegates

authority,

via

the

IANA

URI

scheme

registry

[

<a href="#RFC2718" shape="rect">

RFC2718

IANASchemes

]

deleted text:

for

other

considerations

and

costs

related

the

DNS,

over

a

set

of

URIs

with

a

common

prefix

to

URI

scheme

design.

one

particular

owner.

One

consequence

of

this

approach

is

the

Web's

heavy

reliance

on

the

central

DNS

registry.

Because

of

these

costs,

if

Except

when

a

URI

scheme

exists

that

meets

the

needs

is

constructed

from

a

checksum,

all

of

an

application,

designers

should

use

it

rather

than

invent

one.

</p>

<div class="boxedtext">

<p>

the

techniques

seek

to

establish

a

unique

relationship

between

a

social

entity

and

a

URI.

This

relationship

is

called

<span class="practicelab">

Good

practice:

<a name="pr-new-scheme-expensive" id="pr-new-scheme-expensive" shape="rect">

New

URI

schemes

</a>

</span>

ownership

</p>

<p class="practice">

Authors

of

specifications

SHOULD

NOT

introduce

a

new

URI

scheme

when

an

existing

scheme

provides

.

In

this

document,

the

desired

properties

of

identifiers

phrase

"authority

responsible

for

domain

X"

indicates

that

the

same

entity

owns

those

URIs

where

the

authority

component

is

domain

X.

This

document

does

not

address

how

the

benefits

and

their

relation

responsibilities

of

URI

ownership

may

be

delegated

to

resources.

other

parties

(e.g.,

to

individuals

managing

an

HTTP

server).

deleted text:

</div>

Consider

our

<a href="#scenario" shape="rect">

travel

scenario

</a>:

should

the

authority

providing

information

about

the

weather

in

Oaxaca

register

a

new

A

URI

scheme

"weather"

for

the

identification

owner

may

provide

representations

of

deleted text:

resources

related

to

the

weather?

They

might

then

publish

URIs

such

as

"weather://travel.example.com/oaxaca".

resource

identified

by

the

URI

upon

request.

When

a

software

agent

dereferences

such

a

URI,

if

what

really

happens

is

that

the

HTTP

GET

protocol

is

invoked

used

to

retrieve

a

representation

of

the

resource,

then

an

"http"

URI

would

have

sufficed.

</p>

<p>

If

provide

representations,

the

motivation

behind

registering

a

new

scheme

HTTP

origin

server

(defined

in

[

RFC2616

])

is

to

allow

a

the

software

agent

to

launch

a

particular

application

when

retrieving

a

representation,

such

dispatching

can

be

accomplished

at

lower

expense

via

Internet

Media

Types.

When

designing

a

new

data

format,

the

appropriate

mechanism

to

promote

its

deployment

acting

on

behalf

of

the

URI

owner.

The

URI

owner

has

a

privileged

position

in

the

Web

is

architecture

as

the

Internet

Media

Type.

</p>

<p>

Note

entity

that

even

if

an

agent

cannot

process

representation

data

in

an

unknown

format,

it

can

at

least

retrieve

it.