Report on the Joint W3C-OGC Workshop on Maps for the Web

Translations available: Une traduction français du rapport est ici; 中文翻译在这里

Executive Summary

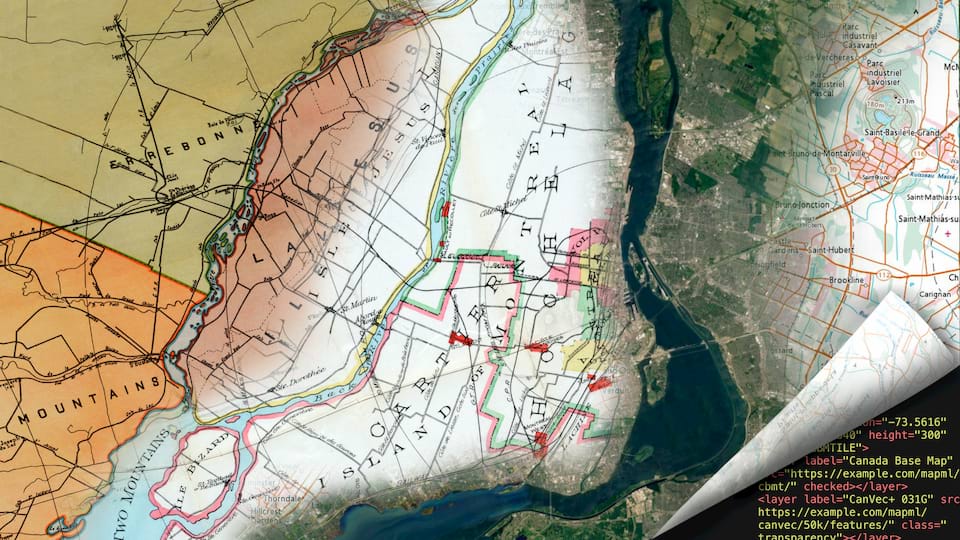

Geospatial information on the Web is fragmented, inadequately covered by Web standards, and lacking interoperability. This raises significant barriers to its effective use. Efforts to standardize geoinformation have focused on established geospatial developers, leaving out the full range of people who communicate with map data on the web. An opportunity exists today to standardize maps and spatial information in HTML, lowering barriers for diverse stakeholders: web developers, GIS (Geographic Information Systems) developers, data providers, map solution providers, commercial geo-app services, and individual web users, in particular the disabled community.

Browser makers are more open than ever to incorporating ideas and code when the web community establishes clear demand for a particular solution. It falls to communities to organize themselves to assert the need for and definition of such standards. The global geospatial information community can and should mobilize to simplify and standardize geoinformation for the Web — maps in HTML — supporting both geographic and non-georeferenced map rendering, along with common interaction patterns.

The workshop gathered a wide range of information, and opinion, on the topic of standardizing maps for the Web. Some participants were hesitant, worried that a standardized solution would be less effective compared to current proprietary offerings. Others cautiously endorsed the idea, with strong encouragement to keep it simple. But there was also outright enthusiasm, with calls to action to standardize web maps in the hopes that that would reduce the barriers to their use by people of all abilities technical, physical, and cognitive.

[A native map HTML element would] definitely let us focus more on what we can do with maps; how we can make nice maps, how we can support users in creating nice maps… the more I think about it, the more I like… the basic concept of … a slippy map…. with that in place, mapping libraries could probably develop in directions that we cannot even think about yet. But this strong focus on the rendering that we have now is definitely in the way of… other kinds of developments.

Andreas Hocevar, OpenLayers developer / OSGeo

The workshop demonstrated the receptiveness on the part of the Web standards community, to the idea of standardizing maps in browsers (the Web Platform), but with the caveat that the work will be costly and time consuming. Web Platform advocates suggest that efforts to standardize maps should be incremental in nature, starting with use cases and requirements, and proceeding to specification and development.

For the geospatial standards community, the Web Platform provides an essential open and even playing field for development and innovation, and for providing access to maps and spatial information to the widest audiences. Given the cautious willingness to cooperate from the Web standards community, the geospatial standards community will need to continue to promote the standardization of maps on the Web, and to increase participation in relevant Web standards development.

This report concludes that the next step forward for this initiative should be negotiation of the terms of reference for a W3C working group that draws its inputs and requirements from relevant W3C, WHATWG and OGC (standards) working groups.

Session videos, transcripts, and supporting material are available from the agenda page of the workshop website.

Introduction

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) sponsored the first joint workshop on standardizing Maps for the Web, which took place online from September 21st to October 2nd, 2020. The workshop was co-led by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC), and convened an organizing committee of individuals from NRCan, W3C, OGC, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), the U.S. National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA), the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), as well as volunteers from the Maps for HTML community. The workshop was initially scheduled to be an in-person workshop co-located with the OGC Technical Committee meeting in June of 2020, but was re-scheduled under an online virtual format, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The workshop was open to the public free of charge.

A call for positions, papers and talks was issued via the workshop website, and was promoted jointly through the W3C and OGC membership communications channels. The workshop was organized by theme, with all themes notionally centered on the idea of standardization of maps in the Web platform. Themes included: accessibility, internationalization, privacy and security, performance, augmented reality, Web map standards and technology, and stakeholder perspectives.

Over 150 registrations were received, with submission of 13 position papers, 33 talks, 7 panels and 3 breakout sessions. All workshop sessions were recorded and each day’s session recording is linked to from the agenda item for that day. Discussion of talks and panels was (and is still) encouraged, and occurred both during the presentations through the live chat, as well as afterwards, with each talk, panel or breakout being the subject of an individual Web standards discussion forum topic. For ease of review, each individual discussion topic links to the specific recording of the presentation or panel.

Workshop Themes

Accessibility (a11y)

The accessibility of existing Web map embedding solutions, as measured against the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), was the subject of an analysis done by Nic Chan and Robert Linder. In short, none of the evaluated Web mapping frameworks meet all the WCAG 2.1 success criteria. For some criteria, none of the evaluated frameworks passed. In response to the evaluation, some of the framework maintainers took steps to improve the accessibility of the framework, which is a promising initial outcome from the workshop.

A summary of requirements for accessible Web maps was presented by Nicolò Carpignoli and Joshue O’Connor. One of the important needs outlined by them is for accessible text-based geolocated “annotations”. In view of standard geographic models, these text annotations correspond to descriptions for OGC Simple Features. This OGC standard describes the common architecture for simple feature geometry, and has already been adopted across several popular standards such as KML, GeoPackage and GeoJSON. Standardizing geo-annotations would require a way to represent these features in HTML. An implicit prequisite for browser support of annotated geographic features is browser control of map rendering (the user agent needs to know where to render the feature). Consequently, the requirements seem to implicitly endorse the basic notion of integrating maps into the HTML and related accessibility standards (CSS, ARIA, WCAG). The presentation also emphasized the need to separate primary information from the background context or surrounding “noise”; in other words, a layer-based model of maps, with a way for assitive technology users to focus on the relevant layer.

The use of maps for improving accessibility of indoor locations was described by Claudia Loitsch and Julian Striegl, whose research has shown that the coverage of indoor maps is today very low. What is more, there exists no single standard today for how maps and geographical data should be made accessible for different contexts and diverse user needs. They conclude that because the market for indoor map data is forecast to grow significantly in the coming years, the aforementioned problems represent the perfect opportunity to develop such standards, before mapping efforts are expended, and potentially wasted, on incompatible solutions.

Physical accessibility relates to facilities that provide access to people with physical disabilities, such as wheelchair ramps and so on. Sebastian Felix Zappe of WheelMap.org suggests that maps in HTML could be used for “disability mainstreaming”, that is, ensuring that accessibility information becomes part of all map services on the Web through standards.

Brandon Biggs from the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute reinforced the importance of presenting the content of maps to blind and visually impaired users. WCAG standards and techniques do not currently encompass the complexity of graphical information in Web maps, or ways to communicate this spatial information to non-visual web users. With new capabilities built into browsers, such as the Web Vibration, Audio and Speech APIs, it is possible to create more advanced nonvisual maps for the Web. To generate the digital auditory or vibro-auditory maps, every feature in a geospatial data set needs both a name and full geometry. The nonvisual maps that Biggs has developed work through spatial collision detection; the user manipulates their virtual position in space, and as that position collides with the feature, the feature name attribute is read out. Existing raster maps and unlabelled vector feature sets do not provide the text descriptions required; even maps that label features as point markers do not suffice, since the scale of the feature in space is unknown. Biggs concludes that without taking into account the data modeling requirements imposed on Web map feature information by nonvisual maps, there would be no point in building a standard HTML component. This points to at least a pair of key requirements to be addressed by a standard for Web maps.

Web Maps for Cognitive Accessibility

The map-related needs of those with cognitive disabilities was the discussion topic of a panel of experts including David Fazio, John Kirkwood and John Rochford, all members of the W3C COGA Task Force. Lisa Seeman, chair of the COGA TF, also contributed to planning the panel, but was unfortunately unable to participate due to a scheduling miscommunication. In sum, the panel members indicated that while a lot of user research remains to be done in this area, broadly speaking, accessible Web mapping technology that responds to COGA users is a huge market, and one to which everyone eventually belongs. Specifically, as the brain ages (more precisely the parietal lobe), function associated to wayfinding (aka navigation, indoors or out) decreases. The key challenge of wayfinding is to find ways to describe spatial information and directions using cues specific to the user’s cognitive abilities. Such cues can be visual or textual, but take different forms for different people. The panel also affirmed that such technology need not be confined to proprietary software, and indeed their task force is working on standards for COGA users. It is to be hoped that collaboration will happen between the relevant standards working groups to bring these needs forwards for map users.

Creating accessible Web map widgets

The workshop brought together a panel of global experts and researchers in the emerging field of Web map accessibility. They discussed issues relevant to the use of Web maps by people with disabilities and in particular those with visual impairments, and what actions the Web mapping community can collectively take to facilitate access to map content and functionality. Panelists included Doug Schepers of Fizz Studio, Brandon Biggs an engineer with the Smith Kettlewell Eye Research Institute, Dr. Tony Stockman from Queen Mary University and Dr. Nicholas Giudice from the University of Maine.

The panel first described the nature of audio maps, and the different types of audio and vibro tactile maps that exist, as well as describing features of these maps and their distinctions, including audio icons (earcons), the relation and similarities between the vision and touch senses, and how such maps may lend themselves to implementations and APIs. The panel also emphasized important considerations or requirements for standardized audio maps, such as the need for name or label attributes for map features, and the need to be able to automatically transform raster data for presentation to auditory or tactile users. The panel also discussed how cartography has well established rules for visual maps, and that there is a need to have cartography develop similar psycho-physical standards for non-visual maps, through research directly involving users.

Tony Stockman, on challenges facing the auditory map domain:

One of the real problems, actually, is the lack of standards for auditory displays in general.

Nicholas Giudice, on challenges facing the auditory and vibrotactile map domain:

…for non visual variants of maps, cartographers…haven’t thought about auditory and vibro tactile map [cartography], and so we need to somehow bake into any type of standard, more empirically derived guidelines for design that… ensure that these elements are both perceptually salient and cognitively meaningful.

Brandon Biggs, about challenges for standards organizations:

There are three [challenges]. One is the data; there needs to be a lot more work with data. The second is the APIs. There’s some future APIs like with XR that are coming out and we need to be thinking about those and how we can represent maps in that way. And the third is getting the users involved in whatever we make.

Brandon Biggs, on how standards organizations can facilitate auditory map innovation:

The thing that needs to happen is we need to make more maps in all different types of modalities…. The biggest problem is that… we haven’t really tried doing BART maps or topological maps of the Grand Canyon, or, you know, different types of maps that are required for being a professional, a geographer.

Augmented Reality (AR)

Jan-Erik Vinje, of Norkart.no, who is Managing Director of the Open AR Cloud Association, gave a presentation on the emerging OGC GeoPose standard. Jan-Erik described what a “GeoPose” is, by comparing it with 2D points of interest (POIs). In contrast to POIs, which can be rendered on a 2D Web map, a GeoPose lends itself to rendering in a 3D globe projection environment, and supports “six degrees of freedom”, meaning a GeoPose can describe the position and rotational orientation of an object in 3D space. Jan-Erik emphasized that GeoPose is attempting to create a standard for describing the behavior of things in the real and virtual world, which tend to move around; their geometry is not fixed in orientation relative to the Earth. It is part of a drive to an open spatial web, which also requires that the representation of things (geometry, semantics, and relationships) needs to be machine-readable and updateable, although this doesn’t exclude the possibility of manual interventions. He indicated that all of these concepts are fundamentally compatible with a map of thematic layers, but in 3D. The “augmented reality” aspect is that map would often represent the real world surrounding the viewer, but could contain virtual objects, such as representations of historical objects, which are overlaid on the physical reality. Jan-Erik argues that a native browser Maps API should support a “globe mode”, which could be the basis for a standardized augmented reality:

…[with GeoPose] support [in] the native map elements… objects in [the] map become especially useful… if we could make sure that the map elements supported the globe mode… like… Cesium or Google Earth.

Christine Perey and Josh Lieberman gave a presentation, about how GeoPose might be integrated with, or supply use cases supporting the Use Cases and Requirements for Web Maps being developed by the Maps for HTML Community Group. They itemized how GeoPose aligns with and extends the use cases for different stakeholders — content author, Web site visitor or application developer — with 3D GeoPosed considerations. Some of the GeoPose-focused additional use cases, such as views along a route from any / different directions, align with the spatial cues considerations for cognitive needs users that were brought forward by the members of the COGA panel.

Josh Lieberman — Open Geospatial Consortium:

There really is a continuum… between a flat map oriented north with a fixed extent and scale and… augmented reality where you really are looking at what’s around you and in front of you and having map objects placed into that view. … [A] Web Map that… is able to transition from… augmented reality to [a] mapped formalism of reality… can really be put into this spectrum…. GeoPose is an important part of establishing that continuum.

A distinguished and enthusiastic panel on AR and 3D mapping brought together AR researchers, entrepreneurs and standards practitioners: Patrick Cozzi, CEO of Cesium, Thomas Logan of Equal Entry, Christine Perey and Jan-Erik Vinje of the Open AR Cloud Association, and Ada Rose Cannon from the Samsung Internet team.

The panel started out with Thomas Logan pointing out that a lot of times when people think of Augmented Reality, they think about the purely visual application, but he noted that sounds can be an important augmentation for people with vision impairments, or for the blind. The panel addressed questions about precision requirements of geospatial information in AR, and how to anchor or relate AR coordinate frames to the real world. The panel touched on game accessibility, and on the important intersection between gaming, graphics, and 3D geospatial technology; they expect that collaboration between these areas will be key for the advancement of AR. The panel also addressed audience questions about the idea of incrementally advancing the Web platform to introduce AR by starting with 2D maps as proposed by the Maps for HTML community.

Jan-Erik Vinje — Open AR Cloud Association:

Thumbs up from me! It’s better to start with [2D native Web maps] and… build on that. If we have native map elements that start out as 2D then the next thing is to extend it. So you could have the globe maps and the immersive modes later on. So, get on with it; that would be wonderful.

Ada Rose Cannon — Samsung Internet:

It would be interesting if there was a native element. Currently Web XR is the only way to do AR in the Web… the best way for it to be able to get into Web XR would be if it was able to expose some kind of buffer, so that the particular web engine you’re using could then take that content and do smart stuff with it to layer it appropriately in your environment.

Thomas Logan — Equal Entry:

2D maps for my kind of world have been a constant challenge from when I got into this world of accessibility. So, I just put it out there to really make sure people do care and consider the [accessibility] use case in 3D.

Patrick Cozzi — Cesium:

I really believe in order to advance AR for maps and to advance 3D geospatial in general, we really need this collaboration, at the intersection of games and graphics and geospatial…. I think we’re really just at the beginning of this kind of fusion of gaming and geospatial.

Internationalization

Brandon Liu’s presentation on “Multilingual Text Rendering” delved into the relationship between text rendering and maps, suggesting that what defines a map is the combination of spatially referenced geometries with textual descriptions, often rendered as labels on the map. Liu suggests that the requirements of correct text rendering need to be considered from a map-specific perspective, and a multilingual perspective, when assessing different Web mapping approaches. Brandon evaluated support for language-sensitive text rendering across browsers and mapping frameworks. He concluded that the deep complexity of text rendering via custom JavaScript or Web Assembly (WASM) processes, combined with the lack of cross-browser support for high-performance, accessible text rendering facilities in graphics standards such as canvas (especially WebGL), favors the use of mapping methods that share and rely on the declarative multilingual text support built into (and improved in tandem with) browser CSS and HTML text rendering. Brandon also specifically advised that there needs to be a lot of care in pushing something as a standard, such as MapML, versus having a low-level set of JavaScript tools that can be used to accomplish something, because, for one thing, a Web standard has to be truly international. For example, he notes that CJK (Chinese-Japanese-Korean) printed maps often have vertical text rendering, but maps on the Web rarely have this. Web browsers do support vertical text, so it would be ideal for Web maps to be able to leverage this feature of browsers. Brandon noted, in response to a question, that ensuring that map text is part of the HTML DOM, whether it is in the user interface to the map or not, is part of the path towards supporting internationalization of maps.

Worldwide Web Maps: Challenges in the global context

The workshop convened a panel of experts on international Web mapping technology challenges which had the idea of standards for Web maps as a backdrop to the conversation. These experts included Brandon Liu, of Protomaps, Thijs Brentjens, of Geonovum, and Siva Pidaparthi, of ESRI. Topics of discussion included: how to improve the state of Web mapping, localizing map content leveraging the work that has gone into browsers’ text support, challenges for security and privacy for geospatial data, map projections and standards, and the importance of accessibility for Web maps users.

Brandon Liu, Protomaps:

For something to become a Web standard, it’s not good to have a half-baked internationalization solution; it’s not good if the solution is just a minimum viable product that only works for left to right, languages, for example…. I’m curious if [the internationalization built into] Web browsers already can influence broader cartographic possibilities for web maps.

Thijs Brentjens, Geonovum:

[Web map accessibility] is a very important topic… [however] it isn’t [very important] in geospatial work… [we have] this idea that maps are visual-only… you can’t make that accessible. So, we just don’t do it. […] It requires us to… start… breaking down the idea… we have that maps are not easy to make accessible because I think there are options.

Siva Pidaparthi, ESRI:

When we are looking at new standards, we should also be thinking about other, different, coordinate systems, not just Web Mercator, or like WGS84, which are good for global data, but for local data they are not very good. We should take additional coordinate reference systems into account.

Privacy

Thijs Brentjens, of Geonovum in Netherlands, gave a presentation on fuzzy geolocation. This arose as a topic of interest at Geonovum because of the debate in Netherlands about COVID-19 tracking apps, specifically privacy concerns about the app capturing and storing user geolocation information of individuals on a server. Consequently, staff at Geonovum discussed how API services might be useful to obscure or provide some randomness in a user’s true interest or location before such locations were transmitted to backend services. Thijs offered to collaborate with interested parties in implementing such a “Fuzzy Geolocation” service or API.

Performance

Andreas Hocevar, core contributor to the OpenLayers Web mapping library, gave a presentation on some research he did, in the Maps for HTML Community Group, into using the Offscreen Canvas API within Web Workers (parallel computing threads within the browser) to enable smoother and faster loading and rendering of tiles in OpenLayers maps, without causing the user interface to hang. Andreas showed a video which emphatically shows the difference in rendering speed of this technology compared with asynchronous fetch (the current standard). Andreas concluded with an appeal to Webkit (Apple) and Gecko (Mozilla) to complete their implementations of the OffscreenCanvas specification, so that mapping and other graphics libraries can deploy these performance improvements across all browsers, interoperability being a core benefit of the Web Platform.

Web map standards and technology

Amelia Bellamy-Royds discussed the common behavior and patterns of Web maps, and the state of development of the Use Cases and Requirements for Web Maps report. She mentioned that if the requirements were to be satisfied by existing frameworks, then no action would be needed, but that does not appear to be the case, particularly when it comes to the accessibility of the user interfaces. Amelia presented examples of various existing Web map technologies and use cases, starting with the existing HTML <map> element for primitive hyperlinked image maps (as used in Environment Canada’s daily weather forecast map). Amelia also showed a Leaflet map viewer used to display a high-resolution zoom and pan painting, as an example of the use case to support non-geographic maps.

Dan “The Ducky” Little presented GeoMoose, which is a mature OSGeo project that began in 2003, and has undergone two major revisions since its inception. It still uses the concept of an XML-based catalog to declare the structure of the application, and its users love this declarative aspect. GeoMoose has evolved through generations of JavaScript frameworks and supports modern formats, such as GeoJSON for features, MapBox Vector Tiles, Cloud-Optimized GeoTiff, and others. Cartographic styling of features continues to be a challenge without direct Web platform support, even though several generations of feature styling, such as MapCSS, SLD, MapBox GL stylesheets, and OpenLayers styles. Performance is not a given even when using hardware-accelerated rendering tools such as WebGL, because map content is often served in data-intensive formats that aren’t optimized for dynamic rendering. GeoMoose has supported OGC protocols, such as WMS and WFS since very early on, and benefited from support via Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) grants to enable sharing of geo information between counties. This meant that GeoMoose installations became widespread across Minnesota and other northern states.

Dan Little offered several points of advice relative to standardizing maps for the Web. First, layer definitions should be decoupled from the source data, as this was a major hurdle encountered by the GeoMoose project. Next, dynamic styling of map features needs to be built in, in a way that is consistent with cartographic practice.

Dr. Gobe Hobona, Director of the OGC API standards development program, gave a presentation on the principles, scope, method, history and plans for the development and roll out of OGC API standards — the next generation of OGC geospatial developer standards, which make use of the OpenAPI specification. The standards specify modular building blocks for access to spatial data provided by Web APIs. As such, the OGC API standards also apply the Spatial Data on the Web Best Practices. To facilitate the development of the OGC API standards, code sprints are held regularly to enable the general public to participate.

Tom Kralidis presented the work of the pygeoapi open source project which is led by himself, Angelos Tzotsos, and Francesco Bartoli. The project is built using the many available geospatial python libraries, and supports many different back end data sources, because of integrating the GDAL spatial engine. It also implements the emerging STAC API and OGC APIs (Features, Tiles, Records) and other API standards. Francesco Bartoli gave a short demonstration of the framework. Tom invited the audience to come over and chat about the project with the developers on the pygeoapi Gitter channel.

Joan Masó from CREAF, and editor of the OGC API — Tiles specification, gave a presentation about the development of Map Markup Language (MapML) through the OGC Testbed program, and about the great potential for integration of MapML with OGC Web services and APIs. Joan mentioned the relation between the Two Dimensional Tile Matrix Set, the Web Map Tile Service and MapML, highlighting the formalization of the URL template in all three standards, and emphasizing that it’s through the application of URL templates that one is able to decouple client and server. He indicated that there is a great similarity between an Tileset Metadata Document (from the OGC API) and a simple MapML document. He concluded that MapML may be the easiest and simplest way to make an OGC Tiles API useful to a browser, especially if the API produces MapML documents.

Jonathan Moules of GeoSeer.net, a geospatial Web services search engine, gave a presentation on the limitations and barriers to discovering map services via his GeoSeer service. The main problem Jonathan highlighted was the existence of hundreds of geoportals. Although there are millions of data sets in his search engine, without the careful manual curation done by GeoSeer, the user would not be able to search for data across portals. He argued that organizations that publish data via these portals don’t produce good metadata, which exacerbates the problem of discovering their services. With about 2M services indexed by his services, there are only about 1500 searches per month. While federation of portals (e.g. cascaded catalog services) is potentially a great solution to one problem, the actual problem is that there isn’t a great demand for service discovery, period. The question Jonathan concludes by asking us is: of these 2M services, spread across so many geoportals, how many of those services exist for sharing vs how many exist to serve the maps for their own use? And, he asks, is it a good use of resources to put data sets onto a geoportal to comply with a regulation (e.g., INSPIRE) when nobody (except the producer, perhaps) seems to be using or searching for the data to use it?

Satoru Takagi, member of W3C SVG Working Group and long time contributor to W3C Web standards on behalf of KDDI Corporation, has developed a Web GIS based exclusively on Web standards, including HTML, SVG, CSS and JavaScript. While Takagi-san shares the goal of decentralized Web mapping that is also an objective of the Maps for HTML community group, he does not believe that changing browsers to natively include mapping code is a practical objective, because maps can already be created by combining existing Web standards, as his work demonstrates. Takagi-san suggests that the Open Geospatial Consortium definition of ‘tile’ concept be expanded to include uniquely performant and adaptive tiling schemes such as his Quadtree vector tiling. He also suggests that the geospatial industry participate in the W3C process directly.

Peter Rushforth of Natural Resources Canada gave a two-part presentation on the MapML Proposal (part one, part two), which is a proposal developed within the Maps for HTML community, to define HTML elements for both embedding map content in web pages and describing map data (vector features and image tile sets, along with corresponding annotations and metadata) within dedicated files. MapML responds to the use cases and requirements to serve both geo-referenced and non-georeferenced Web maps’ needs, via a progressively enhanced <map> and a new <layer> element in HTML, and is designed to support core functionality with an API for scripted enhancements.

Bocoup’s Simon Pieters, a contributor to WHATWG and W3C standards, various browsers, and Web Platform Tests, presented his review of the Maps for HTML Community Group’s documents. Simon indicated that the use cases and requirements for Web maps are very much on track, while his recommendation is that specification and development of browser support for maps be tackled in an incremental fashion. In particular, he suggests that standardization efforts prioritize on fundamental primitives: small pieces of functionality that can be individually exposed and shared by non-geospatial applications. As an example, he pointed to a feature request he raised with the CSS Working Group suggesting that a pan and zoom user interaction pattern (of geospatial and non-geospatial graphical content) should be integrated into browsers natively as an alternative to the text-focused scroll interaction.

Igalia’s Brian Kardell gave a presentation about the scale and scope of Web technology, and the consequent challenges around developing Web standards, highlighting the fact that creating them is costly, risky and long term. He suggests that the mapping community focus on defining shared, scoped objectives that incrementally build support of maps in the Web platform. He offered the services of Igalia to help, and suggested a list of technologies they would be interested in helping with, including: pan and zoom, OffscreenCanvas, hardware accelerated SVG, and others.

Terence Eden, a long time supporter of standardizing map viewers in HTML, gave a presentation that encouraged the Maps for HTML community to ask developers for their opinions on the proposed MapML syntax, to evaluate if it’s too complicated or not explicit enough for them. He emphasized that the Web is an international resource shared by developers of different languages, nationalities, and experiences and that standards are best developed with iterative feedback from them.

Iván Sánchez Ortega gave a presentation in which he outlined his concerns about the implementability of the MapML proposal, or of any purely declarative approach to maps in HTML. He gave examples of existing browser APIs, and speculated on how they could be integrated with maps. For example, the Gamepad API or device orientation APIs could be used to manipulate map views, but not if the map viewer is a black box controlled by the browser. He also described how WebGL textures have similarities to GIS raster coverage data: tiles of GeoTIFF multi-spectral imagery should be considered as 256x256x7 mini data cubes. He speculated that image processing for satellite information in the future will be done in the browser as “edge computing”, because of the incredibly powerful APIs that the Web Platform provides to all developers, and he questioned how such powerful APIs will work with MapML.

Iván went on to emphasize that standardization is a choice, and to suggest that MapML cannot solve the commercial and/or legal issues which underlie why maps on the Web are fragmented and non-standard. Iván gave the specific example of the GoogleMutant Leaflet plugin, which uses the Google API together with the Web standard Mutation Observers API to overlay and synchronize Google and Leaflet viewers, because the Google Maps Terms of Service forbid direct rendering of Google image tiles via non-Google viewers (such as Leaflet). Ivan asserts that hacks like his GoogleMutant plugin should not be necessary, and that map vendors should instead expose content via standard APIs that allow map data from multiple sources to be integrated together in the browser. Iván asserts that the proposed MapML standard interface will not change map vendors’ behavior, but instead will only duplicate the functionality (non-standard interfaces) already available in JavaScript mapping frameworks.

Daniel Morissette of MapGears gave a presentation about MapGears’ implementation of MapML in MapServer, GDAL and OGR. Daniel’s presentation showcased the willingness of some experts in the FOSS4G community to help push adoption of proposed Web standards, and provide opportunities for experimentation and feedback, through integration of new map data formats into widely used open source geospatial server software.

Karel Charvat gave a presentation on the “Map Whiteboard” technology, together with a breakout session on the whiteboard techology” his project has created. A map whiteboard is a map that acts much like a shared Web document (e.g., like a Google Doc, or a MS Teams document), allowing simultaneous editors and viewers at the same time, dynamically saving and updating each other’s view of the content as it changes. The Map Whiteboard is built using the open source OpenLayers JavaScript mapping framework, and relies on a Map Compositions JSON document, which extends what the old OGC Web Map Context XML document type did, with many modern features.

Kathi Schleidt, on behalf of herself, Hylke van der Schaaf and Thomas Usländer, gave a presentation about the challenges of Web mapping dynamic and observational data and metadata obtained from sensors. The OGC SensorThings API follows the OData RESTful API architecture; the challenges addressed by the project include properly scaled map layer display where multi-scale data is available. The SensorThings model is useful because it allows you to formulate your queries based on the graph defined by your data model, and the resulting queries work well using the RESTful OData API. The challenges of displaying SensorThings data on maps at multiple scales is handled by their JavaScript library that works with both Leaflet and OpenLayers, which accepts a JSON configuration object that allows you to calibrate it for use in your application, and it is available on GitHub.

Karl Grossner, technical director of the world historical gazetteer, who works at the University of Pittsburgh, gave a presentation on a proposed time extension to GeoJSON, called “GeoJSON-T”. GeoJSON is a Web geodata encoding standard for transmitting and consuming features, their properties and geometry, based on the widespread OGC Simple Features model. The GeoJSON-Time proposal extends the standard model with a “when” member, which allows the encoding to describe, in a standardized way, the time in which the feature is relevant. The structure of the “when” member is not finalized, but is designed to encompass both precise and fuzzy times, and time ranges. The GeoJSON-T proposal is used by the digital humanities community, but could ideally be shaped and adopted outside that community as well.

Bryan Haberberger, IIIF Maps Technical Specification Group Chair, gave a presentation on his work which creates semantic annotations for cultural resources not owned by his organization, using GeoJSON-LD, an integration of the GeoJSON standard (for encoding geographic vector features in JSON data files) with JSON-LD (Linked Data), a method of annotating data objects with references to standardized schema defining their structure. GeoJSON-LD is based on JSON-LD 1.1, because the original version of JSON-LD does not support lists of lists, which are required for the GeoJSON polygon geometry type. Additionally, Bryan discussed the Web Annotation standard model, which enables creating GeoJSON-LD annotations for any Linked Data resource and geolocating it.

Nicolas Rafael Palomino gave a presentation in which he explained his views on how and why geospatial information standardization is essential in preparing for a digital-friendly future. Overall, he recommends advancing the objective of standardizing maps in HTML.

Government Stakeholders

Danielle Dupuy of the US Geological Survey (USGS) presented on the automation benefits of declarative data-driven map styling. The USGS has developed a system that stores map type and style information in a database, and which presents a central location to edit the declared values of certain map properties, including maps’ symbols, color, size, and “pane” (an internal Leaflet abstraction which could be described as z-index ‘categories’). These map ‘properties’ can be manipulated easily by non-developers, and they reduce or eliminate the need for developer intervention in the map-making process. The USGS has found the system a boost to productivity, and they plan to apply the technique to other projects.

Chris Little, an Information Technology Fellow of the UK Met Office, gave a whirlwind overview of the history and future of cartography and meteorology. It was a fascinating tour through thousands of years of the evolution of maps and spatial information management technology, concluding with some offered insights as to the current needs and potential future trends. First, Chris observes that the current Web map “layer” metaphor is “broken” for meteorological charts and maps. The combination in charts of 100s of “levels”, at 100s of time points or intervals, with 100s of data ensembles yields millions of possible layers. He predicts the integration of spatial information and browsers over a 10-year time scale, without being specific about how that integration will or should occur; however, he emphasizes that the current technological environment is particularly fertile for such growth to occur. Chris indicates that his preference would be to start the integration of map technology into the browser with 3D content, and derive 2D content as a product of that integration, which would make certain classes of problem easy / easier to solve.

Sajeevan G. gave a presentation about the Web GIS application supporting the Indian Prime Minister’s Rural Road Programme (PMGSY). The PMGSY application has a 15+ year history, including migrating from a commercial GIS-based application to a Web interface, based on Web service standards, open source and commercial software. Dr. Sajeevan notes that while the application is capable of producing and consuming OGC standard services, many businesses still require to accept feature content as shapefiles only. It is expected that future OGC Web APIs will be an integral part of feature transactions in the future. Regarding standardizing maps in HTML, Dr. Sajeevan emphasizes the importance of local coordinate systems and recommends that a Google Earth-like globe view be considered essential in a future standard for Web maps. A spherical viewer avoids having to specifying map projections in the standard, by allowing the viewer to do on-the-fly deprojection to the globe view at runtime. The viewer should be able to consume external map data services, supporting both raster and vector (feature) data types. Dr. Sajeevan foresees enormous contributions from the developer community into a browser based HTML map viewer, and sees geospatial data services as an emerging business opportunity as a result.

Stakeholders: Government geospatial data providers & the web

A government stakeholder panel was convened to discuss the importance of geospatial information to governments and what impact a standard for Web maps might have on their organizations’ goals. The panel included Sébastien Durand, manager of the Canadian Geospatial Platform (CGP), Cameron Wilson, manager of the GeoConnections Program at Natural Resources Canada, Emilio López Romero, director of the National Centre of Geographic Information of Spain, and Don Sullivan, a geospatial scientist and standards expert with NASA AMES Research Center, and one of the original authors of the Web Mapping Service OGC standard. A key point made by Sébastien was that Web maps provide a view of data in context that is unique and almost magical in its ability to turn data into knowledge. Generally, the panelists were receptive to or enthusiastic about the proposal to standardize and integrate maps in browser technology, specifically via OGC APIs and HTML, because they believe that such an integration would lower the barriers to better use of public spatial data infrastructures, as well as providing an interoperable standard for a “common operational picture” that cuts across JavaScript frameworks.

Don Sullivan, NASA Ames Research Center:

When I heard about… maps on the web and maps as first class citizens. I went, oh my God, yeah. So I’m here… as a champion. I think this is just an amazing idea that has been way too long in coming out. I’ve been waiting for this for over 20 years now.

Stakeholders: Open Source for Web Mapping

A panel of open source geospatial and browser developers discussed what needs to happen in order to bring map support into Web browsers. Tom Kralidis of OSGeo and numerous Geopython projects moderated a panel of experts which included Simon Pieters of Bocoup, Daniel Morissette of OSGeo/MapGears, Will Mortenson from NGA’s Gnome program, and Andreas Hocevar of OpenLayers/OSGeo. The panel discussed collaboration between the Web and geospatial communities, and what it takes to contribute ideas and requirements to HTML standards and browser code bases. As well, the panel discussed the issues that Web mapping libraries face that could be made more tractable with better browser support for slippy map intefaces, in areas such as performance and styling of vector features, without which Web map framework developers and content authors must master complex, low-level APIs such as WebGL.

Daniel Morissette, MapGears / OSGeo:

A good example of a standard that did work and nobody could kill, even though it’s simple, and could be called flawed, is the Web Map Service (WMS). If it’s good enough, people are going to use it, and if the map integration in HTML is good enough, it’s gonna win over time.

Will Mortenson, NGA Gnome Program:

I gather requirements from customers and users; …as a government guy, I don’t necessarily know everything… [about how Web browsers work.] So, if we had people… from the public side [who] could stress why [investing in maps in browsers is] important, [the government could invest] money towards these efforts.

Andreas Hocevar — OpenLayers / OSGeo:

[A native map HTML element would] definitely let us focus more on what we can do with maps; how we can make nice maps, how we can support users in creating nice maps…. The more I think about it, the more I like… the basic concept of… a slippy map…; with that in place, mapping libraries could probably develop in directions that we cannot even think about yet. But this strong focus on the rendering that we have now is definitely in the way of… other kinds of developments.

Simon Pieters — Bocoup:

Browser developers and map framework developers need to talk to each other and get an agreement on use cases and requirements and how we can change the browser to better address those needs in a well designed way. …when designing solutions in [this] space…. …Maps should be accessible to people who use screen readers… by default, insofar as [they] can be. But for more custom rendering, when you use canvas or WebGL, then accessibility is hard to get by default, but you will need to make it possible to layer in, somehow.

Commercial Mapping Stakeholders

Ted Guild of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) chaired a panel of stakeholders from the commercial mapping platforms, including Ed Parsons (Google), Johannes Lauer (HERE, formerly Nokia, maps), Daniel Lewis (Geotab), and Thomas Lee (Mapbox). This group of stakeholders found common ground on issues related to Web mapping, and they thoughtfully approached the workshop theme of standards for Web maps while addressing a diversity of topics, including: the potential benefit of client-side map standards for improving the agility of product iteration, the benefits and limits of open (government, and other) data for map content creation, the importance of rendering performance for client-side map content, how simple use cases such as rendering GeoJSON on top of base maps unlock enormous value; the value of vector tile information for creating accessible interfaces and styling, and improving performance; the need of further work to develop data licensing approaches that mirror the advanced state of open source software licensing, the prospect of 5G technology improving maps for everyone, how semantic textual annotation/markup embedded in Web pages can relate importantly to locations and maps, and the coming indoor mapping revolution.

Daniel Lewis — Geotab:

…[During] disaster[s]… the ability for decision makers to quickly go in and get access to that kind of data..ultimately the point of this stuff is… [to] make decisions based on it… having the ability to quickly iterate on that… is really important. […] Interoperability is… a key thing going through all of this…; baking that standard into the tool that everybody uses… immediately starts to break down the silos….

Tom Lee — Mapbox:

For us, unlocking performance is really important. Moving to a native implementation could really unlock some additional performance. …anything that can be done to unlock more performance will push the frontier forward and if standardization can be part of that, then that’s really great.

Ed Parsons — Google:

My message is, we need to be more mainstream. We need to be much more standard citizens of the web as opposed to creating our own separate Geospatial web where we did things differently.

Conclusion

Wendy Seltzer — W3C Strategy Lead and Counsel:

…As strategy lead at W3C I’m excited to hear the discussion here and we’ll welcome any follow up that you have for places that we can fill gaps in existing standards work or new work that you might like to see started at the W3C, that the team is here to help.

Web mapping standards have previously focused on server-side technologies and infrastructure, and there is a robust set of standards for map servers which closely interact with universal modern client-side techniques such as tiled “slippy maps” that can be panned and zoomed. Because these techniques are de facto standards between all web map providers, and have been stable for some years, there are common factors that would clearly benefit from formal client-side standardization: tiling, panning, zooming, coordinate reference systems, layers, accessible map features (e.g. geometric areas of interest), and more.

Another impetus for standardizing maps is improved accessibility in web maps, which was a major theme of the workshop. Several surveys of existing mapping frameworks demonstrated a fundamental lack of accessibility, which needs to be addressed in web standards.

Next steps

The next logical step is to begin the discussion for how a working group should scope these features in its charter. The two main points for discussion are what is and is not in scope for the first charter, and whether to define higher-level map-specific features or to break the functionality down into more generic primitives that can solve a wider set of use cases beyond maps.

The charter should also define the relationship and coordination between server-side and client-side map standards, and specifically, the W3C working groups that should be consulted and collaborated with in order to achieve the best possible result. There is a mutual relationship between W3C and OGC which includes a joint working agreement that would facilitate bringing together the right stakeholders and relevant working groups from both organizations.