Abstract

A lot of effort goes into writing a good specification. It takes more than knowledge of the technology to make a specification precise, implementable and testable. It takes planning, organization, and foresight about the technology and how it will be implemented and used. The goal of this document is to help W3C editors write better specifications, by making a specification easier to interpret without ambiguity and clearer as to what is required in order to conform. It focuses on how to define and specify conformance for a specification. Additionally, it addresses how a specification might allow variation among conforming implementations. The document is presented as a set of guidelines or principles, supplemented with good practices, examples, and techniques.

Status of This Document

This section describes the status of this document at the time of its publication. Other documents may supersede this document. A list of current W3C publications and the latest revision of this technical report can be found in the W3C technical reports index at http://www.w3.org/TR/.

This document is a W3C Working Draft (WD), made available by the the QA Working Group of the W3C Quality Assurance (QA) Activity for discussion by W3C members and other interested parties. For more information about the QA Activity, please see the QA Activity statement.

This is the second published version of this document after the decision to completely redesign the QA Framework (QAF), resolved by the QA Working Group (QAWG) at its 2004 Technical Plenary face-to-face. It is a lighter-weight, less authoritarian, more user-friendly and useful version of the previously published Candidate Recommendation version of the QA Specification Guidelines. Because of the extensive nature of the changes, it has been returned to Working Draft.

This draft accurately reflects the intended overall structure and content of the new, lightweight QA Specification Guidelines. However it is incomplete in some details (generally indicated by "@@" or "TBD" or "ISSUE"), especially in the examples -- lots more examples are intended. Also, some sections more resemble outlines than completed prose. Because this is a significant departure from the last-published QA Specification Guidelines, QAWG wants review and comment on the overall direction as soon as possible. Incomplete details will be fleshed out in the next publication.

This QA Specification Guidelines document will be coordinated with the other parts of the QA Framework, The QA Handbook [QA-HANDBOOK] and QA Framework: Test Guidelines [QA-TEST] (Progression and publication of this document is temporarily on hold, though you can still participate to its development). Synchronization at uniform level of maturity will occur no later than Last Call.

The QAWG expects this specification to become a Recommendation. The plan is to publish a Last Call Working Draft at the end of October 2004.

Publication as a Working Draft does not imply endorsement by the W3C Membership. This is a draft document and may be updated, replaced or obsoleted by other documents at any time. It is inappropriate to cite this document as other than work in progress.

Patent disclosures relevant to this specification may be found on the Working Group's Patent disclosure page in conformance with the W3C Patent

Policy of 5 February 2004. An individual who has actual knowledge of a patent which the individual believes contains Essential Claim(s) with respect to this specification should disclose the information in accordance with section 6 of the W3C Patent Policy.

Comments on this document may be emailed to www-qa@w3.org, the publicly archived list of the QA Interest Group. Reviewers please note that your comments will be publicly archived and available, do not send information that should not be distributed, such as private data. If you are able to give your feedback by 1st October 2004, the QAWG can consider it at its next face-to-face meeting. The comments will still be collected after the face-to-face meeting in October 2004.

Table of contents

Appendix

Introduction

Scope and Goals

This document is a guide for W3C editors and authors. It provides guidelines for writing better specifications. This document differs from other W3C process and publication related documents in that it looks at specifications from a conformance viewpoint. It address the most basic and critical topics with respect to conformance, including how to convey what is required in order to conform and how to allow variation among conforming implementations. The goal is to make specifications precise, easier to interpret without ambiguity or confusion, and clearer as to what is required in order to conform. Good specifications lead to better implementations and foster the development of test suites and tools. Conforming implementations lead to interoperability.

Motivation

Everyone benefits from having well-written specifications. Editors may have less rework and thus, fewer errata. Implementers can implement sooner and have a better chance to conform to the specification. Test developers are able to derive unambiguous requirements. Users benefit by having interoperable solutions. W3C gains by having recommendations produced with higher quality and reduced maintenance.

Why Specification Guidelines?

It is not an easy task to write accurate, clear, complete, unbiased specifications. It requires planning, organization, and foresight about the technology, how it will be implemented and used, and how technology decisions affect conformance. This document provides a collection of principles, good practices, examples, and techniques that leads the reader though the decisions that need to be made in order to write precise requirements and establish, define, and specify conformance for specifications. Realizing that editors and authors are busy, under pressure to get the specification published, and already have a reading list of W3C documents (a good place to start, W3C Editor's Home Page [EDITOR] this document can be used as a checklist or reminder of things to consider, a how-to guide with examples and techniques which can be adapted, a reference for understanding conformance concepts and terminology, or all of these.

About this document

This document is a practical guide to writing a specification, presenting editors with topics to consider. Consequently, much of the document is non-normative recommendations labeled Good Practices. There are however, a limited number of normative requirements, labeled Principles, that must be implemented in order to conform to this document. The overall objective of these principles and good practices is to facilitate the creation of a conformance clause in every specification. A conformance clause template [CONF-TEMPLATE] is provided to assist editors satisfy the requirements of this document and end up with a conformance clause. Note that for some specifications (e.g., The QA Handbook [QA-HANDBOOK], Architecture of the World Wide Web, First Edition [WEB-ARCH]) where conformance is not an issue (e.g., no normative content), the conformance clause may be an explanation of why there is no "conformance to this document" which may not be a separate section but incorporated into another section.

The topics presented are inclusive (self-contained) providing information needed to understand and successfully apply the principle, although related information and advanced topics may be referenced.

If in a hurry - start at the first section, Specifying conformance -- this is the expected outcome of adhering to this document. It serves as a roadmap to other parts of this document, which help you achieve specifying conformance.

Audience of this document

The primary audience of this document is editors and authors, however, it is applicable to a broader audience including:

- those who review specifications during their development

- implementers of specifications

- builders of test materials, including conformance test suites and tools.

This document makes no distinction between the terms editors and authors and will refer to them collectively as editors.

Structure of this document

This document is organized in a series of main topics like Conformance or Extensibility. In each of this main topics, a few principles are developed and explained. Theses principles are accompanied by techniques and examples. The techniques illustrate basic (and non exhaustive) questions or methods that might help you create a specification. The examples are explanations or extract of specifications which specifically address the point which has been made in the principle.

The conformance requirements of this document are described in the conformance section of this document.

The keywords "MUST", "MUST NOT", "REQUIRED", "SHALL", "SHALL NOT", "SHOULD", "SHOULD NOT", "RECOMMENDED", "MAY ", and "OPTIONAL" will be used as defined in RFC 2119 [RFC2119]. When used with the normative RFC2119 meanings, they will be all uppercase. Occurrences of these words in lowercase comprise normal prose usage, with no normative implications.

This document can be used as a stand alone document or as part of a family of QA Framework documents designed to help the WGs improve all aspects of their quality practices.

- The QA Handbook [QA-HANDBOOK] is a non-normative handbook about the process and operational aspects of the quality practices of W3C Working Groups (WG).

- The QA Framework: Test Guidelines [QA-TEST] is a document to help W3C Working Groups to develop more useful and usable test materials. The material is to be presented as a set of principles and good practices.

Guidelines

Clear presentation of what is meant by conformance to the specification is ultimately crucial to successful interoperability of implementations. The conformance policy and language in the specification not only determine its testability, but also shape the overall look of its implementations landscape -- are there numerous fragmented flavors or a few strong, interoperating variations?

Conformance is the fulfillment of a product, process, or service of specified requirements. These requirements are specified in a standard or specification as either part of a conformance clause or in the body of the specification. A conformance clause is a section of a specification that states all the requirements or criteria that must be satisfied to claim conformance to the specification.

With a good conformance clause, a specification comes close to full conformance to this QA Specification Guidelines.

The conformance section of a specification — commonly called the Conformance Clause — is a high-level description of what is required of implementers and application developers. It, in turn, may refer to other parts of the specification for some details. Ideally, it is the root source from which readers can find any conformance-related information.

For some specifications, the conformance landscape may be plain and simple, and the conformance clause template may be almost all that is needed [Example?]. For others, the conformance landscape will be complex or convoluted, and the advanced details and topics of these QA Specification Guidelines — topics like managing variability (section D) — may be invaluable.

ISSUE: There's still an issue from Lofton if we should define here the way the normative language is defined.

The central message of this section -- “have a good conformance clause” --has many ancillary details. Because the conformance clause is the foundation for defining and measuring conformance, it is also the basis for assessing conformance claims. One detail worthy of attention is “valid conformance claims”.

Rather than live with the infinite varieties of creative conformance claims that will arise in a vacuum, the specification can be proactive:

Good Practice:

Provide an Implementation Conformance Statement (ICS) proforma.

What does it mean? An Implementation Conformance Statement (ICS) provides standardized information about the conformance of an implementation to the specification. It is used to indicate which capabillities and options have been implemented, as well as the limitations of the implementation. An ICS typically takes the form of a questionnaire for implementor to complete.

This Good Practice suggests that the specification itself include an ICS proforma. (Caveat. The ICS concept may be inapplicable to some types of specifications.)

Why care? An ICS provides detail about conformance. View the ICS as a template, where

its organization, format and content can provide implementers and users a

quick overview of the specification's features, options, subdivisions of

the technology, conformance requirements, etc. It can be especially

valuable as a statement of conformance, where implementers indicate which

mandatory features and options they implement and document the presence of

extensions. Once completed by an implementer it can be used as part of the

conformance claim. Additionally, an ICS can be used to identify the subset

of a conformance test suite that would be applicable to the implementation

to be tested.

Technique

- Create a list, table or form listing all features (capabilities) and indicating if it is mandatory or not.

- Provide space for the implementer to check: Yes, No, Not Applicable

- Organize the features according to the subdivisions of the specification or in the order they occur in the specification or in some other logical grouping

- If there are dependencies, express them. (For instance, if No to this question, jump to the next section.)

- You may want give a tool that will help the implementors to fill the ICS and have a formatted report (for example, with EARL).

Examples

QA Specification Guidelines provides an ICS [QA-SPEC-ICS] to help developers to verify the conformance to this document. Good practices (informative) and Principles (normative), organized following the sections of the document, are given in a table where developers can check yes, no or not applicable.

Good Practice:

Require an Implementation Conformance Statement (ICS) as part of valid conformance claims.

What does it mean? This simply puts together the previous two good practices. Not only could the specification provide an ICS proforma for implementors, but it could require it to be linked from its standardized conformance claim template.

Why care? Providing a filled ICS with the conformance claim might help customers and users to verify easily the level of support of individual requirements of the specifications. It also strengthens the value of the claim.

Technique

- Explain in the conformance claim section how the developer must fill the ICS

- Give precise instruction how the ICS must be part of the conformance claim. It might be an external document, it might a link to precise dated document, etc.

B. The Nature of the Specification

B.1. Scope

The path to a quality specification begins with its scope. It is critical to convey what the specification is about by describing its intent and applicability. As the specification develops, it is a good idea to revisit the scope to make sure it still reflects the intent of the specification or if it needs to be modified.

Principle:

Define the scope

What does it mean?

Describe what the specification is about. Let the reader know what is covered in the specification.

Why care?

It helps to keep the specification content focused. It also will help readers know the limits or boundaries of the specification and whether it is of interest to them.

Technique

- Include a scope section in the beginning of the document.

- Make it a table of content items

- In addition to describing the subject of the specification, address the following to achieve a more complete scope:

- Applicability of the specification,

- Purpose, objectives, and goals,

- Types of products or services (i.e., classes of products) to which the specification applies,

- Relationship to other specifications or technologies,

- What is not in scope, i.e., what the specification is not about,

- Limitations on the application of the specification.

Note that it is not necessary to write a separate statement for each of these items, rather, they can be combined.

Examples

Many W3C specifications have included a scope prose in the abstract section. As it is important that the scope is somehow defined it is a lot better to put that in a separate section as explained previously.

Good Practice:

Write simple, direct statements in the scope.

What does it mean?

When writing the scope, be direct and write simple, understandable statements of facts. Don’t include any requirements in the scope section.

Why care?

This one of the first sections a reader reads, so it is important to capture their attention and make sure they understand what the specification is about.

Technique

Use statements such as: This document

- specifies a method of …

- specifies the characteristics of …

- defines …

- establishes s system for …

- establishes general principles for …

- is a guide for …

Good Practice:

Use examples or use cases to illustrate

ISSUE: Ongoing work from the QA WG.

Principle:

Identify who or what will implement the specification

What does it mean? Clearly identify the class of products (i.e., type of products or services) to which the specification applies. If multiple classes of products are targeted by the specification, make sure each are described. Examples of classes of products include: content, producer of content, player, protocol, API, agent, guidelines.

Why care? It helps define the scope of the specification and is needed when defining conformance. It also helps the reader know what is being targeted by the specification – that is, to discover and focus on what they have turned to the document for and avoid what they may find immaterial.

Technique

- Think about all the types of products or services that will implement this technology, group those that are similar and/or basically achieve the same purpose, and determine the generic name for the group. This would be the class of product.

- List the classes of products that will implement the specification.

- Describe them somewhere at the beginning of the specification.

Examples

QA Framework: Specification Guidelines defines one class of product – specifications

The conformance section of Ruby [RUBY] is very explicit and detailed about classes of product. For each of these classes, Ruby conformance

section defines a set of rules, the implementers or the users must

respect. It defines rules for markup, dtd, document, module, generator,

interpreter.

Schema Part 1 [XML-SCHEMA-1] could be said to define an abstract notion of “schema validity” but this checkpoint can only be satisfied if the Recommendation says explicitly whether it is setting expectations of an XML parser or of a “schema validator” that could be stand-alone.

Schema Part

2 [XML-SCHEMA-2] defines data types, so it is a specification of type 2 above — content/data — and it is used as a foundation by other specifications (e.g., XPath 2.0) as well as being part of the schema validator and hence parser requirements. The specification could define the behavior of a data-input tool that rejects data not fitting the schema, but it probably would not because the tool would be expected to use a parser module to validate the data. To satisfy this checkpoint, the Schema Part 2 specification has to make clear whether it is to be taken as an independent specification of a parser (that produces data from arbitrary strings) or a foundation to be used by other specifications.

B.3 Make a list of normative (and non-normative) references

ISSUE: Björn Höhrmann has raised an important issue about the way normative references are given and their implications on the normativity of the specification itself. An short abstract of the issue can be foreseen as:

- When making a normative reference, you need to see how future versions of the said specification may affect your own document

- Address the way you "use" the conformance model of the referred specification

The QA WG is still discussing the issue. You are welcome to participate on the QA IG Mailing list (www-qa@w3.org publicly archived), but read first this two mail threads:

D. Managing Variability

Specifications allow some sort of variation between conforming

implementations for different goals, e.g. adaptation to a particular

hardware capacity, possibility to use extensions ; this

variability, while often wanted to allow a broader usage of

the technology, may have bad consequences on interoperability and needs

to be carefully designed to find the right trade-off.

This section gives advices to help finding this balance; the reader

would also gain to read Variability in Specifications

[VIS] which goes into more details on the analysis of

this variability.

D.1 Subdivide

Subdividing the technology should be done carefully. Too many divisions complicates conformance and can hinder interoperability by increasing the chances of conflict with other aspects of the specification (e.g., other subdivisions). Be smart when dividing the technology so that it is not excessive and provides a positive impact on implementation and interoperability. The benefits of subdividing should outweigh the drawbacks.

Benefits: Subdividing can

- make the technology easier to implement

- facilitate incremental implementation

- increase interoperability by focusing the technology on specific needs

- help organize the structure of the technology

- provide better normative guidance than SHOULD provisions of the "core" spec

- provide names for feature bundles, facilitating automated negotiation between sending and receiving products

Drawbacks: Too many divisions can

- complicate conformance – need to account for interrelationships with other subdivisions and variability (e.g., extensions)

- hurt interoperability – increases likelihood of incompatible implementations

- increase misinterpretation or cause conflict of requirements due to multiple or duplicative requirements.

Good Practice:

Subdivide the technology to foster implementation

What does it mean?

It may make sense to subdivide the technology into related groups of functionality to target specific constituencies, address specific capabilities or hardware considerations, provide for incremental implementation, facilitate usability, etc.

Why care? :

For some specifications (e.g., huge, multi-disciplined), bundling functionality into named or anonymous packages can

- provide an additional level of scoping control,

- improve readability and the ability to find areas of interest, and

- facilitate implementation and interoperability, since implementing the entire, monolithic specification may be impractical and undesirable

Technique

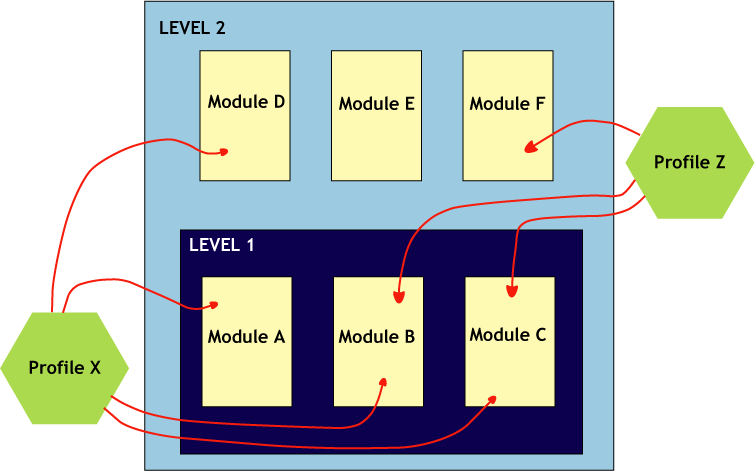

- Use profiles. Profiles are subsets of a technology tailored to meet specific functional requirements of application communities. The specification may define individual profiles, or may define rules for profiles, or both. An individual profile defines the requirements for classes of products that conform to that profile. Rules for profiles define validity criteria for profiles themselves.

- Use functional levels (aka levels). Functional levels are a hierarchy of nested subsets, ranging from minimal or core functionality to full or complete functionality. Levels are a good way to facilitate incremental development and implementation.

- Use modules. Modules are discrete collections of semantically-related units of functionality that do not necessarily fit in a simple hierarchical structure. Use modules when functionality can be implemented independently of one another e.g., audio vs video module. It is common to have implementers pick and choose multiple modules to implement.

Examples

Levels: There are no examples in W3C where levels are defined explicitly in a single edition of a specification. CSS and DOM technologies are examples where levels are the result of progressive historical development and technology enrichment and are realized in a series of specifications.

STOP: Only proceed if you did the above Good Practice. Else, skip the rest of this section.

Principle:

If the technology is subdivided, then indicate which subdivisions are mandatory for conformance

What does it mean?

Regardless of the subdivision technique (i.e., profile, level or module), state whether one or more of the subdivisions is required for conformance.

Why care?

Subdividing the technology affects and can complicate conformance with all the various combination of choices it provides – (a Chinese menu syndrome – 1 from column A, 2 from column B and desert is included). Thinking about the various possibilities helps to structure the conformance model, taking into account how the subdivision will affect various classes of products. Implementers as well as users need to know what is mandatory, optional, prohibited or conditional with respect to choosing what to implement and be conformant.

Technique

In the conformance clause, list the subdivisions that are mandatory for conformance. To help build this list, consider the following questions.

- Can an implementation conform without implementing one of the subdivisions?

- Does the subdivision apply to specific classes of products and not others?

- Are there combinations of the subdivided technology that always go together and can not be implemented alone?

Examples

Content can be required to conform to one of the subdivisions (e.g., profiles) or it may be conformant to the specification independently of a subdivision. The question arises for a producer (of content): is it conforming if it generates content that is otherwise valid but does not conform to the subdivision.

WCAG 1.0 [WCAG10]

defines three levels of Conformance depending on the levels.

XHTML Modularization [XHTML-MOD]

defines minimal requirements for including certain basic modules if you designed a conformant XHTML Mod document.

Principle:

If the technology is subdivided, then address subdivision conditions or constraints

What does it mean?

This is a corollary to the Principle above. Beyond being mandatory or not, subdivisions usually have conformance consequences due to minimal or new requirements, restrictions, interrelationships, and variability, etc. As part of the conformance clause, describe the conditions or constraints associated with each subdivision

Why care?

Creating subdivisions can get complicated, not just for the specification editor but for implementers who must pick and choose from the set of subdivisions. Well designed subdivisions that convey the conditions, constraints, interrelationships, etc. will improve the clarity and understanding of the specification, conformance to the specification and facilitate implementation and interoperability.

Technique

In the conformance clause, describe the conditions or constraints on subdivision usage. To help accomplish this, model or graph the subdivisions indicating the following that applies:

- Atomicity of the subdivisions: Represent each subdivision showing its atomicity.

- Mandatory subdivisions: Label the subdivisions that are mandatory

- Minimal requirements: List minimal requirements for each subdivision.

- Dependencies among subdivisions: Show dependencies and interrelationships of the subdivisions. For example, modules that requires and builds on functionally related modules, i.e., modules that require modules from other functional areas.

- Conditions and constraints on subdivisions groups: Indicate conditions and constraints for combined occurrences of subdivision pairs or groups:

- Conditions or constraints associated with specific classes of products: Indicate which conditions and constraints are applicable to specific classes or products.

- Other conditions or constraints beyond these: Indicate any other conditions or constraints.

Examples

[@@ would be great to graph/model a technology]

Good Practice:

Define rules for creating profiles

What does it mean?

If profiles are used and profiles can be developed outside the specification itself, then provide the rules for creating these derived profiles. These profile rules provide instructions for building profiles (e.g., requirements on structure, functionality, encoding, etc.). Derived profiles should not contradict predefined profiles, if there are any in the base specification.

Why care? : Well-defined rules will facilitate the creation of derived profiles that are well-specified, implementable, and testable. If these rules are followed, then the derived profile will conform to the specification.

Technique

- Create two particular profiles

- Identify the common requirements in these two profiles

- Identify the rules that you have followed to create these profiles and write them done

- Try to create a third profile using the defined rules

D.2 Optionality and Options

Options in specifications provide implementations the freedom to make

choices about

- whether or not to support a well-defined feature,

- which value or behavior to choose from a well-defined enumerated set of possibilities,

- implementation dependent values or features.

These choices also called discretionary items, give implementers of the technology the opportunity to decide from alternatives when building their applications and tools.They describe or allow optionality of behavior, functionality, parameter values, error handling, etc. They may be considered necessary because of environmental conditions (e.g., hardware limitations or software configuration), locality differences (e.g., language or time zones), dependencies on other technologies, or the need for flexibility.

Although there are perceived benefits to providing options, there is also a downside: options increase the variations that can exist among

implementations. The greatest way to undo the utility of a specification is with too many options. Basically, different implementations may specify different combinations of options. This makes comparisons between

implementations difficult as well as complicates conformance testing and

increases the chance of non-interoperable implementations.

Story:

A concise XSLT 1.0 [XSLT10] example: implementers have been granted separate discretion about all of the following aspects of creating attributes in the output:

- Whether to raise an error when the supplied name is not a valid QName

- Whether to raise an error when an attempt is made to create an attribute after children of the element have been created

- Whether to raise an error when an attempt is made to create an attribute on a node that is not an element

- Whether to raise an error when the content of an attribute is not plain text

- Whether to raise an error when two attribute-sets of the same precedence contain an attribute of the same name

- Whether to raise an error when attempting to create an attribute directly under the root of a result tree fragment

In each case, there is one prescribed behavior for an implementation that chooses not to raise an error. Thus, the 6 separate binary choices give rise to 64 different possible behaviors for conformant processors. Typically, an implementer would be content to make a more global choice about raising errors when there is an attempt to create non-well-formed XML results.

Good Practice:

Determine the need for each option. Make sure there is a real need for the option.

What does it mean?Examine the reason for the option - is it to address a real, existing need? Should it really be an option or made a mandatory part of the specification? Be careful not to provide options in anticipation for something that sounds like a good idea but will probably never be realized - ask the implementers if they ever plan to need this. As the specification progresses, if the option is not implemented, consider removing it.

Why care? A concise list of options helps to keep the specification focused and will greatly increase the likelihood of obtaining interoperable solutions. Ensuring that only necessary opotions are contained in the specification also makes the job of the implementer easier and reduces costs.

Technique

Develop a set of tests and analyze the results

to see what is implemented and how it is implemented.

Examples

Tests were used to determine if options were needed. As part of its exit criteria for Candidate Recommendation, a Working Group created a set of tests to 'test the specification'. The tests were able to show where there was need for optionality (e.g., diversity among implementations and flexibility justified) and where it was possible to narrow the choices (e.g., implementations used a much narrower set of values than what was permitted).

Good Practice:

Indicate any limitations or constraints

What does it mean? Provide as much information as possible to narrow the allowable choices and to increase predictability.

For implementation dependent values or

features, if possible, provide a range or set of permitted values rather than

leaving it completely open.

Why care? Narrowing choices and increasing predictability enhance the likelihood of interoperability since the sample space for the implementer to choose from is diminished. Narrow choices and providing more information also increases the chances of correct implementations since incorrect choices are eliminated. An enumerated list of values is one way to constrain the choice of optionality.

Technique

For options, especially enumerated lists, make sure that the number of choices/options that can be implemented is known. Specifically, can zero, exactly one, or several of the allowable choices be implemented? Does this number depend on other parts of the specification or other chosen options?

Examples

CSS 2.0 [CSS20] defines often properties the constraints on the values that can take these properties. For instance, the property font-weight can have the following value and only these ones: “normal | bold | bolder | lighter | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | inherit” and a default value being “normal”

In XPath 2.0 [XPATH20] and its associated functions, the WG intends to require support for collation by Unicode code-point, and allow implementations to implement as many other collations as they wish.

Good Practice:

Address the impact of the option

What does it mean?Think about the implications of both implementing the option and of not implementing the option

Discuss the implications of either using the option or not. It may be helpful to provide rationale for choosing one option over another or for not using the option at all. Consider the unintended consequence of the option - on other options, other parts of the specification, on other specifications.

Why care? Thinking about implications of options forces the specification developers to seriously consider the utility of each option, which may eventually lead to the elimination of unnecessary options. Discussiong the implications of using the option or not and providing rationale as to why to choose one option over another allows implementers to make informed choices, and to understand the consequences, both intended and unintended, of their decisions.

Technique

Questions to consider include:

- What affect will implementing the option have on a conforming

implementation, on interoperability?

- Is there any affect or negative consequence if the option is not

implemented?

- Must the option be implemented?

- Is there a default value for the option?

- Are there any dependencies, that is, the option can only be implemented

if certain conditions are true?

- Are the options mutually exclusive, that is, can one option override

and void another?

Good Practice:

Make options easy to find. Use tags to label options.

What does it mean? Options can be useful, but non-judicious use of options increases the variability among conforming implementations. In order to minimize the unnecessary optionality, it is necessary to be able to easily identify them.

Why care? To make it easier for implementers, test creators and users to discover the choices and variability allowed. For test creators, having a name for each item and a link target for each one, allows systematic reference to individual items from test cases as well as elsewhere in the specification. In addition to its benefits for writing test cases, the use of labels for options helps in constructing pro formas, conformance claims, comparisons between two implementations, reports to the W3C Director about implementations, etc.

Technique

Options can be tagged in many ways. Any technique that distinguishes the optional feature from the required feature is acceptable. Some psssibilities include:

- putting options in a separate section;

- specifying options in a different font (be careful of accessibility and printing problems);

- including a unique designation to identify an option.

D.3 Extensibility and Extensions

To accommodate changes in technology and information on the Web, a

specification can be designed for extensibility. A specification is

extensible when it provides a mechanism to allow any party to create

extensions. Extensions incorporate additional features beyond what

is defined in the specification. However, extensions can compromise

interoperability if there are too many differences between implementations.

The impact of extensions can be mitigated through features specifically

designed to allow new functionality. These features provide a 'standard way

to be non-standard' by including hooks, conformance rules, or other

mechanisms by which new functionality may be added in a conforming way.

Principle:

Address the extensibility topic inside specification.

What does it mean? Extensions might be encouraged or discouraged by the Working Group. There is a benefit to addressing the value or danger of extensibility for the technology which is currently being developed. Formalizing the position of the Working Group by a clear defined section and prose will remove ambiguities for the specification users about the possibility of developing extension or not.

Why care? There is a strong likelihood that developers will create extensions to a specification, because they have specific needs which are not covered by the specification. Writing clearly how the extensions need to be developed will help ensure that extensions are defined in a consistent manner leading to predictable handling of extensions and minimize issues such as: interoperability problems, minimal support, and harmonious future development.

The WG may consider that the technology is complete, self-sufficient and and doesn't need any extensions. In this case, it is necessary to write this clearly in the specification and to explain why the technology is not considered extensible. It might be just for the social benefit of the community to ensure a maximum interoperability.

Technique

- Create a section of your specification dedicated to the extensions topic

- Call it Extensions

- Make a table of contents entry for it

- Address the following principles and good practices of this section

Good Practice:

Define the extension mechanism

What does it mean? Extensions increase variability between implementations. Defining a mechanism will help to ensure extensions are defined in a consistent manner leading to predictable handling of extensions, including the ability to take appropriate actions (e.g., do the extension, ignore, or take a fall-back behavior).

Why care? By planning for extensions and designing a specification for extensibility, there is less chance that extensions will interfere with conformance to the base specification and a better chance at achieving interoperability. On the other hand, there may be areas in a specification that would not benefit from extensibility and extensions are strictly forbidden (e.g., permissible characters in XML 1.0 names for elements and attributes, most of the built-in datatypes in Schema Part 2). This is called strict conformance. Strict conformance is defined as conformance of an implementation that employs only the requirements and/or functionality defined in the specification and no more.

Reasons for designing extensibility into a specification include:

- providing a stable, useful framework to manage the rapid pace of

technology change,

- reducing the chances that extensions will interfere with conformance and

increasing the chances for achieving interoperability,

- providing the ability to 'test-drive' new functionality that may

migrate into future specifications,

- enabling implementers to include functionality that they consider to be

required by their customers.

Technique

Technology and

application needs will dictate the best strategy for enabling

extensibility.

When designing for extensibility, it can get complicated. Questions to

consider that can impact design decisions include, but definitely not limited

to:

- Does the conformance section address the use of extension?

- Is there a well defined template to create exension?

- Does this mechanism prevent the creation of extension conflicting with the semantics of the specification?

- When needed, is the scope of extensions is defined? (e.g., Are extensions authorized only for certain parts of the technology?)

- As an exercise, create a fake extension to illustrate problems that could arise interacting with the specification?

- As an example, create a fake extension as an example for developers what would be the right way to do it?

- Can extensions interact with other extensions?

- Can extensions be combined?

- Can the extension mechanism be propagated? (e.g., Using the extension mechanism of Specification UNO, Specification TOO is created. Can this same mechanism be used create Specification TOOTOO, an extension of Specification TOO?)

- Can extensions apply to a specification's profiles or modules and not the core part of the specification?

Examples

Mechanism defined within the specification, extension indicator, error handling instructions

XSLT 1.0 [XSLT10] provides extension mechanisms that allow an XSLT style sheet to determine

whether the XSLT processor by which it is being processed:

- has implementations of particular extensions available,

- and to specify what should happen if those extensions are not available.

It defines two boolean functions: function-available (QName) and element-available (QName) that must be present in every implementation. These functions inform the XSLT processor that there is an extension, therefore the XSLT processor can return a value of false and provides handling instructions (e.g., signal an error, perform fallback and not signal error), if the extension is not available.

WSDL 2.0 [WSDL20] defines binding extension elements which are used to provide information specific to a particular binding. It is a two-part extensibility model based on namespace-qualified elements and attributes. It provides the syntax and semantics for signaling extensions. Extension elements can be marked as mandatory, meaning that they MUST be processed correctly by the WSDL processor - i.e., either agree to fully abide by all the rules and semantics signaled by the extension or immediate cease processing (fault).

Mechanism based on another specification's extension mechanism

CC/PP exchange protocol based on HTTP Extension Framework [CCPP-EXCHANGE] defines a HTTP extension to exchange

CC/PP descriptions effectively. The CC/PP exchange protocol conforms to

HTTP/1.1 and is a generic extension mechanism for HTTP 1.1 [HTTP11] designed to inter-operate with existing HTTP applications. The CC/PP exchange protocol uses an extension declaration to indicate that an extension has been applied to a message and possibly to reserve a part of the header namespace. It provides rules for which of the HTTP Extension Framework [HTTP-EXTENSION] extension declaration strengths and extension declaration scopes to use and defines the syntax and semantics of the header fields.

OWL Reference [OWL-REF] is a vocabulary extension of RDF Semantics (See section 6 in [RDF-MT]). OWL imposes additional semantic conditions on RDF called semantic extensions of RDF. These semantic extensions conform to the semantic conditions for simple interpretations described in the RDF Semantics Recommendation. The OWL semantics is consistent with RDF semantics, but OWL when understood as RDF is 'incomplete' versus the same OWL when understood as OWL. Thus, by understanding OWL more is learned and nothing that is learned contradicts what is learnt by RDF alone.

Mechanism defined as conformance rules

In XHTML Modularization [XHTML-MOD], the conformance section defines a set of conformance rules to allow for the extension of XHTML's layout and presentation capabiltiies. This method uses the extensibility of XML without breaking the XHTML standard. It defines the

extension by using XML DTD or Schema which is uniquely identifiable, does not

redefine behavior of the technology it extends, and the syntactic and

semantic requirements are described and documented. Additionally, it cn have

some organization and naming constraints defined by the technology it

extends.

CSS3 module: Syntax [CSS3-SYNTAX] has an vendor specific extension mechanism perfectly described. The CSS WG has established a strict set of rules to define extensions which are:

A proprietary name should have a prefix consisting of:

- an underscore ("_") or a dash ("-"),

- the (possibly abbreviated) name of the company, organization, etc. that created it,

- an underscore or a dash.

Good Practice:

Define error handling for unknown extensions.

What does it mean? Include error handling instructions for when an extension is not available or understood.

Why care? When using a strict conforming application, users might have to deal with documents, data which are considered invalid because they are containing errors, or they are extended. Developpers will need to know what must be the behavior of the application in such context.

A consistent error handling helps interoperability with regards to usability. There is the well known Postel law which says "Be Strict in what you produce, Be tolerant in what you accept". Though it has been shown that often this has been the start of a nightmare for implementers who have to deal with all the possible cases to recover from exotic documents (non conformant or extended). Giving a consistent error handling mechanism eases the work of developers.

Technique

There are typically two approaches: (see section 4.2.3 Extensibility from Architecture of the World Wide Web, First Edition [WEB-ARCH])

- Must ignore: ignore any content it does not recognize. Must ignore can be further refined, requiring that the unknown item be passed through unchanged to the next downstream process, while other technologies simply discard it.

- Must understand: treat unrecognized markup as an error condition.

A good way to handle these two approaches is to have a way in the syntax to distinguish which behavior is expected, e.g., mustUnderstand attribute in Soap 1.2

Don't forget to address all your classes of products. For example, an authoring tool and a rendering tool might have to behave in a different way or not.

D.4 Deprecation

The need for deprecation comes about when there are features (e.g., function argument, element, attribute) defines in the specification that have become outdated and is being phased out, usually in favor of a specified replacement. It means that the feature is still there and functional, but

- there is a better way of achieving the same thing and the WG prefers you use this better way

- or the feature is not being used and the WG wants to clean up the specification and eventually remove the feature.

From a user point of view, a deprecated feature is one that should not be used anymore, since it may be removed from future versions of the specification. Deprecated features are no longer recommended for use and may become obsolete and no longer defined in future versions of the specification.

Principle:

Identify each deprecated feature.

What does it mean? When a new version of a technology evolves, it is important to provide a list of the features being deprecated from the previous version of the specification. This list serves to notify developers and users of the technology.

Why care? It helps developers know which features will be superseded in the next version of the technology. Moreover, it provides them time to remove it from their code and if appropriate implement an alternative method.

It helps users of the technology know which features to avoid using when they create documents.

Technique

- Create a list of all features that are not encouraged anymore.

- Create a dedicated section for it

- Create a entry in the table of content going to this list

- For each deprecated feature, create a link to the appropriate definition in the specification

Examples

HTML 4.01 [HTML401]: The specification has a full list of elements and attributes. The deprecation status is given in the two lists. There is an entry in the table of content to these two lists. Each element/attribute is linked to its definition in the specification

Principle:

Define how to handle each deprecated feature

What does it mean? By deprecating a feature, the WG indicates its desire that the feature disappear from the specification. The motivation may be to convert an old feature to a newer one or to remove an old, dangerous, redundant or undesirable feature. Regardless of the reason, it is important to define the affect this will have on implementations that may encounter this feature (e.g., consumer products such as user agents or producer products such as authoring tools). Will use of the deprecated feature be tolerated? Will it signal an error or a warning?

Why care? Defining how deprecated features are handled provides a smoother transition for the users of the specified technology, and ensure more consistency of the behavior across implementations. It is also particularly important for implementations that needs to support different versions of the specification.

For instance, the specification may require that an implementation

supports both the features of the new and the old specifications, or

suggest a converting mechanism.

Technique

- Consider the effect of deprecation on all classes of products that implement the specification (e.g., authoring tools, converter, user agents).

- Specify the degree of support required for each deprecated feature.

- Define its conformance consequence.

Examples

HTML 4.01 [HTML401]:

In the conformance section of HTML 4.01, there is the definition of deprecation and what user agents should do. Though the behavior for other kind of products is not defined.

User agents should continue to support deprecated elements for reasons of backward compatibility.

Good Practice:

Explain how to avoid using a deprecated feature

What does it mean? The use of a deprecated feature is discouraged because there is a better technique already available to achieve the same result. For each deprecated feature, it is necessary to explain how implementers and users can avoid using it. It might be helpful to give additional information providing insight into the deprecation motivation.

Why care? Examples and information about each deprecated features will help users to smoothly evolve toward the new version of the technology, understanding its benefits. It will help to have a faster adoption of the technology.

It will help developers understand the rationale for implementing the new technology, to implement an alternative mechanism, and to tool tips or conversion scenarios to help users with the transition.

Technique

- For each deprecated feature, give one or more examples showing the old way and the new way. If the new way is explained in another document, you might want to give a link to this document, though don't forget that often readers benefit of having everything in one place.

- For each deprecated feature, give an explanation why the Working Group has decided to deprecate the feature. What are the benefits?

- Say if the given example is a generic mechanism or a specific example. Users of the technology might adopt the specific example in their implementations and it will limit the use of the feature.

Examples

Namespaces XML

1.1 [NAMESPACES11] deprecation of IRI references includes a link to the deprecation ballot results,

providing background information on the proposal to deprecate, what this

means with respect to conformance to XML 1.0 and Namespaces as well as the

affect on other specifications (i.e., DOM, XPath).

HTML 4.01 [HTML401] gives numerous examples on how to avoid the markup which was used in previous versions for deprecated elements.

Good Practice:

Identify obsolete features

What does it mean? A feature which has been deprecated in a previous version of the specification was at risk of being removed. Making it obsolete indicates that the feature is no longer in use and removed from this present version of the technology. Providing a list of obsolete features informs developers and users what is no longer in the specification.

Why care? It gives a clear message to users and developers that obsolete features are forbidden and not part of the specification anymore. It helps avoid the creation of documents mixing old and new techniques which will be invalid.

It helps avoid name clashing. When an extension to a technology is created, developers will use syntax token for their extended features name. Giving the name of obsolete features will help developers to avoid using the names of previous features which are now obsolete.

Technique

- Create a list of all features that are obsolete.

- Create a dedicated section for it.

- Create a entry in the table of content going to this list.

- For each deprecated feature, create a link to the appropriate definition in the previous specification.

Examples

HTML 4.01 [HTML401]: The specification has a full list of elements and attributes. The obsolete status is given in the two lists. There is an entry in the table of content to these two lists. Each element/attribute is linked to its definition in the specification

HTML 4.01, Appendix A: Changes lists the elements that are obsolete and suggests an alternative element for use. The following elements are obsolete: LISTING, PLAINTEXT, and XMP. For all of them, authors should use the PRE element instead.

D5. Error Handling?

Good Practice:

Define an error handling mechanism

What does it mean?

For a language, address what effect an error (be it syntactic or

semantic) in the input has to a processor of this language.

For a protocol, address how should behave a party to this protocol when

a bogus message is received.

Why care?

There are many reasons a system may fail; to make a technology reliable,

it is crucial to define how it should react to bogus input.

Defining error handling also makes it possible for a user of the

technology to react appropriately to the error condition.

Technique

Different methodologies exist to handle errors in a technology:

- in a protocol, defining well-known error messages allows better recovery and or reporting of these failures

- in a language, syntax errors (non-parsable content) and semantic errors (meaningless content) can be handled separately or together; in both cases, one should keep in mind that extensibility may need new tokens ([WEB-ARCH], extensibility), which can be smoothen by the use of "mustIgnore" and "mustUnderstand" policies: in the first case, a processor is required to ignore only the content that it cannot understand, in the second one, it is required to consider as an error that kind of content

- try and limit the number of types of error defined by the specification; also, having errors of the same kind being processed the same way allows greater interoperability

Examples

the XSLT 1.0 specification allows a processor to recover to some of

the defined errors,

http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-xslt-19991116#conformance

E. Do Quality Control

As all editors know, the work is not finished when the writing is completed. In fact, various review and checks of all W3C documents are required prior to their publication and advancement. There are many things that can be done to improve the quality and clarity of the document, aside from the W3C process and publication rules and before Last Call reviews. Many of these things can be an integrated part of the specification development. Ensuring a quality document prior to external reviews can save time and energy in that the Working Group may get fewer comments and issues to resolve.

Example: One Working Group's document entered CR prior to a through

quality review, resulting in a huge number of issues to resolve and the

eventual retreat back to Working Draft for major revisions. Many of the

comments could have been prevented, such as: inconsistency and incompleteness of the document (e.g., links to supplementary materials which did not exist or were not complete, overlapping and conflicting requirements), undefined terminology, and unimplementable requirements.

Example: When defining a language (such as XHTML) some requirements are defined in a natural language (e.g., English) while others are defined using a formal specification. Often there is overlap between the two approaches - especially with XML Languages where a DTD or an XML Schema can be used for two purposes: to define the syntactic requirements set by the language and/or to allow validating documents conforming to the said language. This overlap can lead to contradictions between the prose and the formal language, i.e., the prose says more than the formal language, formal language is more constraining than the prose, or the formal language says something different than the prose.

When a working group is developing a technology, each WG individual member could be tempted to add as many features as possible (because it will be cool, because it is needed here or there, etc.). But adding these features doesn't mean:

- that it would be easy to implement them: Benefit/Cost for each individual features.

- that it would be implementable: When you come to the implementation phase, you see that in fact, it doesn't make sense at all or it's impossible to implement.

- that it doesn't fit in the bigger scheme of things: For example, two features in the spec that would have opposite or contradictory behaviour without mutual exclusion mechanism (The two features must not be present at the same time).

Principle:

Do quality control during the specification development.

What does it mean? The more the specification work is organized, the more chances you get control on development process of your specification, the more chances to move smoothly across W3C Process, and to have a better final product. Each time, a version of the document is published, the WG must ensure that each individual section, whether a full chapter or simply the explanation of a given feature, is coherent and complete.

Why care? Publishing a specification with incomplete section is very damaging at many levels :

- Image of the WG

- Understanding of the technology

- Possibility of good review and comments from people outside the WG.

All these issues will tend to slow down the process and the advancement of the development of the technology.

Technique

- Create, at the start of the work on the specification, guidelines to help people progress on the technology and write submissions for the specification.

- Follow some or all of these following good practices

- If you really need to put an incomplete section, make it clear that

- It's incomplete

- Be clear about comment expectations -- are comments and contributions desired, or should readers ignore the section for now?

- Divide the work in small units, so people can see regular progress

- Quality can be fun, make it fun.

Examples

@@RDF/OWL organization for submitting tests.@@

@@SVG - experiment of a feature, a test case@@

QA Specification Guidelines: For the edition of each Good Practice and Principle of QA Specification Guidelines, a template and a method has been given to make the edition of each part easy to follow and discuss by the QA Working Group and easy to incorporate in the final document for the editor.

Good Practice:

Do a systematic and thorough review.

What does it mean? Each part of a technology should be reviewed by the WG before publication, but also during the editing phase. It will help the Working Group to identify missing pieces, spelling mistakes, ambiguities, dependencies. With a well defined review process inside the Working Group, it should not be difficult to accomplish this task.

Why care? When a Working Draft is published with incomplete or very raw sections, the WG might receive a lot of comments which will have to be answered at best or the incomplete text will go unnoticed and appear in the final Recommendation at worst.

Technique

- Create a simple and light review process. Perhaps, establish a team, where each person focuses on a different aspect of the specification's correctness.

- Organize at least one review cycle before publication (more if you can)

- Organize the review by topic and expertise. For example, each person checks a different part of the specification or do it by expertise - the grammarian checks for consistency, grammar, spelling, readability, the test builder checks requirements for precision and implementability, the conformant checks that conformance criteria exists.

Examples

XHTML 1.0: If you submit a web page address to the W3C MarkUp Validator, it could happen that the result page tells you that your document is "Valid XHTML 1.0 Strict" and provides a link to the XHTML 1.0 Recommendation. If you follow this link you will encounter a problem: There is no definition of what it means for a document to be identified as "Valid XHTML 1.0 Strict".

For QA Specification Guidelines, a template ([QA-SPEC-TEMPLATE], archived mail) was produced to guide authors, ensuring that each principle and good practice was written consistently and addressed the same set of information. Once a principle or good practice was written, the text was circulated to the entire WG for comments and at the same time, a specific member of the WG was assigned to review the text. This ensured that at least someone in the WG had the reviewing responsibility and it would not fall through the cracks. Multiple authors produced the QA Specification Guidelines, following a template

Good Practice:

Write sample code or tests.

What does it mean? For each feature, the WG might seek early implementation to demonstrate the feature. If early implementations are not available (e.g., due to commercial constraints, IPR, etc.), it is beneficial to write test cases to illustrate a concept or use case of the technology. Additionally, these test cases can be incorporated into a test suite.

Why care? Developing a partial implementation (sample code) or test cases can provide an understanding of a concept or feature as well as help to keep it focused. It can save the WG and eventually implementers time and resources by:

- providing examples to illustrate the specification

- facilitating issue resolution

- helping to have a pre-implementation report at CR phase

- contributing to the development of a complete Test Suite

- encouraging external implementations and therefore a more complete implementation report.

Technique

- Encourage developers (Open Source or Commercial) to work with the Working Group to get pre-implementation at the same time the technology is developed.

- For each feature, request that WG members provide at least one test case demonstrating the use of the feature.

- Do not put a feature into a specification without the corresponding test cases.

- Create an authoring template for how to define/describe a feature which include a test case section.

Examples

@@CSS editors are encouraged (required?) to provide tests with all new content.@@

Good Practice:

Write Test Assertions.

What does it mean? A test assertion is a statement of behavior, action, or condition that can be measured or tested. It is derived from the specification's requirements and provides a normative foundation from which one or more test cases can be built.

Why care? Test assertions facilitate the development of consistent, complete specifications and promote the early development of test cases. This exercise helps to uncover inconsistencies, ambiguities, gaps, and non-testable statements in the specification. It can provide early feedback to the editors regarding areas that need attention. An added benefit is that the assertions can be used as input to test development efforts.

Technique

- Try to write assertions as you add features to a specification. If you can't write the test assertion for the feature it suggests that there is a problem in the way you have designed or explained the feature.

- Create an authoring template for how to define/describe a feature which includes a section for adding test assertions.

- Identify all requirements in your specification and try to write corresponding test assertions.

Examples

When trying to write test assertions for all its conformance requirements, one Working Group found that informative information was needed to complete the normative requirement. Consequently, the conformance requirements were rewritten.

SOAP

version 1.2 Test Assertions [SOAP12-TA]

Assertion x1-conformance-part2

Location of the assertion: SOAP 1.2 Part 1, Section 1.2

Text from the specification: The implementation of an Adjunct MUST implement all the pertinent mandatory requirements expressed in the specification of the Adjunct to claim conformance with the Adjunct.

Comments: This statement applies to all assertions in part 2 and as such will not be tested separately.

HTML 4.01 Test Suite [HTML401-TEST]

Assertion 6.14-1

Reference: Section 6.14

(must) Script data ( %Script; in the DTD) can be the content of the

SCRIPT element and the value of intrinsic event attributes. User agents

must not evaluate script data as HTML markup but instead must pass it on as

data to a script engine.

Tests: 6_14-BF-01.html

XML Test Suite [XML-TEST]

Section: Documents

Type: Well_Formed

Purpose: A well formed document must have one or more elements one

Level 1

Conformance to the QA Framework: Specification Guidelines is very simple.

- It applies to one class of product – Working Group specifications (i.e., technical reports).

- It is monolithic – no modules, levels or profiles are defined.

- It has only one conformance label, called ‘conformance’.

- It has options, but the options do not affect conformance.

- It allows extensions, but the extensions do not affect conformance.

The conformance requirements of this document are denoted as Principles. All Principles are written in imperative voice, with the assumed “you must” in front of the statement. In addition to Principles, the document contains Good Practices. Good Practices are optional and considered recommendations. Their implementation or non-implementation does not affect conformance to this Specification Guidelines document.

To conform to this Specification Guidelines, all Principles must be implemented.

One way to satisfy the Principles and Good Practices is to implement one or more of the suggested techniques given for each Principle and Good Practice. Note that this is not the only way to satisfy the Principle or Good Practice. An Implementation Conformance Statement is provided for assistance in keeping track of which Principles and Good Practices are implemented. It takes the form of a checklist [QA-SPEC-ICS]. If all the Principles are checked as being satisfied, then conformance can be claimed.

Normative Parts

The normative parts of this specification are identified by markup and style as well as the labels, ‘normative’ and ‘informative’ within sections. The following list indicates the normativity of parts in this specification.

Text that is designated as normative is directly applicable to achieving conformance to this document. Informative parts of this document consist of examples, extended explanations, and other matter that contains information that should be understood for proper implementation of this document.

Specification Guidelines Extensibility

This specification is extensible. That is, adding conformance related information and structure to the document in ways beyond what is presented as Principles in this specification, is allowed and encouraged. Extensions to this specification must not contradict nor negate the requirements in this specification.

Conformance claims

To claim conformance to the QA Framework: Specification Guidelines, Working Groups must specify:

- guidelines title and dated URI: QA Framework: Specification Guidelines, URI

- URI of a dated version of the specification for which conformance is being claimed,

- date of the claim.

Examples

ISSUE needs good examples.

Acknowledgments

The following QA Working Group and Interest Group participants have

contributed significantly to the content of this document:

- Jeremy Caroll (HP)

- Patrick Curran (Sun Microsystems),

- Dimitris Dimitriadis (Ontologicon),

- Karl Dubost (W3C),

- Dominique Hazaël-Massieux (W3C),

- Lofton Henderson (CGM Open),

- Björn Höhrmann,

- Susan Lesch (W3C),

- David Marston (IBM Research),

- Lynne Rosenthal (NIST),

- Mark Skall (NIST),

- Andrew Thackrah (Open Group),

- Olivier Théreaux (W3C).

References

Normative References

- CONF-TEMPLATE

- Specification Guidelines Conformance Clause Template, Lofton Henderson, Lynne Rosenthal, 30 August 2004, available at http://www.w3.org/QA/2004/08/SpecGL-template-root.html .)

- QA-GLOSSARY

- Comprehensive glossary of QA terminology.

(Under construction, at http://www.w3.org/QA/glossary.)

- RFC2119

- IETF RFC 2119: Key words for use in RFCs to Indicate Requirement Levels, S. Bradner, March 1997. Available at

http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2119.txt.

-

CCPP-EXCHANGE

-

CC/PP exchange protocol based on HTTP Extension Framework

, Hidetaka Ohto, Johan Hjelm, Editors, W3C Note, 24 June 1999, http://www.w3.org/1999/06/NOTE-CCPPexchange-19990624 . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/NOTE-CCPPexchange .

-

CCPP-VOCAB

-

Composite Capability/Preference Profiles (CC/PP): Structure and Vocabularies 1.0

, L. Tran, F. Reynolds, M. H. Butler, C. Woodrow, J. Hjelm, H. Ohto, G. Klyne, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 15 January 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-CCPP-struct-vocab-20040115/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/CCPP-struct-vocab/ .

-

CSS20

-

Cascading Style Sheets, level 2 (CSS2) Specification

, H. Lie, I. Jacobs, C. Lilley, B. Bos, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 12 May 1998, http://www.w3.org/TR/1998/REC-CSS2-19980512 . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-CSS2 .

-

CSS3-SYNTAX

-

CSS3 module: Syntax

, L. Baron, Editor, W3C Working Draft (work in progress), 13 August 2003, http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/WD-css3-syntax-20030813 . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-syntax .

-

CSS-TEST-DOC

-

CSS Test Suite Documentation, Tantek Çelı̇k, Ian Hickson, 29 January 2003, http://www.w3.org/Style/CSS/Test/testsuitedocumentation-20030129.html

Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/Style/CSS/Test/testsuitedocumentation.html .

-

DOM-CORE-3

-

Document Object Model (DOM) Level 3 Core Specification

, P. Le Hégaret, G. Nicol, L. Wood, M. Champion, J. Robie, S. Byrne, A. Le Hors, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 7 April 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-DOM-Level-3-Core-20040407 . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/DOM-Level-3-Core/ .

-

EDITOR

-

W3C Editors' Home Page

, Communication Team, Available at http://www.w3.org/2003/Editors/ .

-

EXT-SPECGL

-

QA WIKI

Extension Speclite

, Available at http://esw.w3.org/topic/ExtensionSpeclite .

-

HTML401

-

HTML 4.01 Specification

, A. Le Hors, D. Raggett, I. Jacobs, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 24 December 1999, http://www.w3.org/TR/1999/REC-html401-19991224 . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/html401 .

-

HTML401-TEST

-

HTML 4.01 Test Suite

, Available at http://www.w3.org/MarkUp/Test/HTML401/ .

-

HTTP-EXTENSION

-

IETF

An HTTP Extension Framework

, H. Nielsen, P. Leach, S. Lawrence, February 2000 Available at http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2774.txt .

- HTTP11

- IETF RFC 2616:

Hypertext Transfer Protocol — HTTP/1.1, J. Gettys, J. Mogul, H.

Frystyk, L. Masinter, P. Leach, T. Berners-Lee, June 1999. Available at

http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2616.txt.

-

MANUAL-STYLE

-

W3C Manual of Style Susan Lesch, Available at http://www.w3.org/2001/06/manual .

-

MATHML20

-

Mathematical Markup Language (MathML) Version 2.0 (Second Edition)

, P. Ion, R. Miner, D. Carlisle, N. Poppelier, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 21 October 2003, http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/REC-MathML2-20031021/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/MathML2/ .

-

NAMESPACES11

-

Namespaces in XML 1.1

, R. Tobin, T. Bray, A. Layman, D. Hollander, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 4 February 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-xml-names11-20040204 . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/xml-names11/ .

-

OWL-REF

-

OWL Web Ontology Language Reference

, M. Dean, G. Schreiber, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 10 February 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-owl-ref-20040210/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-ref/ .

-

OWL-TEST

-

OWL Web Ontology Language Test Cases

, J. De Roo, J. J. Carroll, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 10 February 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-owl-test-20040210/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-test/ .

- QA-HANDBOOK

-

The QA Handbook, L. Henderson, Editor, W3C Working Draft (work in progress), 30 August 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/WD-qa-handbook-20040830/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/qa-handbook/ .

- QA-SPEC-ICS

-

QA Specification Guidelines ICS, Karl Dubost, 30 Août 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/WD-qaframe-spec-20040830/specgl-ics.html

- QA-SPEC-TEMPLATE

-

QA Specification Guidelines Template, Karl Dubost, 10 June 2004, http://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/www-qa-wg/2004Jun/0023.html

- QA-TEST

-

QA Framework: Test Guidelines, D. Dimitriadis, P. Curran, Editors, W3C Working Draft (work in progress), 20 August 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/WD-qaframe-test-20040820/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/qaframe-test/ .

-

RDF-MT

-

RDF Semantics

, P. Hayes, Editor, W3C Recommendation, 10 February 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-rdf-mt-20040210/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-mt/ .

-

RUBY

-

Ruby Annotation

, T. Texin, M. Suignard, M. Ishikawa, M. Sawicki, M. J. Dürst, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 31 May 2001, http://www.w3.org/TR/2001/REC-ruby-20010531 . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/ruby/ .

-

SMIL20

-

Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language (SMIL 2.0) Specification

, E. Hodge, P. Hoschka, K. Kubota, J. van Ossenbruggen, E. Hyche, M. Jourdan, L. Rutledge, B. Saccocio, W. ten Kate, P. Schmitz, R. Lanphier, N. Layaïda, J. Ayars, T. Michel, D. Bulterman, D. Newman, A. Cohen, K. Day, Editors, W3C Recommendation, 7 August 2001, http://www.w3.org/TR/2001/REC-smil20-20010807/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/smil20/ .

-

SOAP12-TA

-

SOAP

version 1.2 Test Assertions, Available at http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/REC-soap12-testcollection-20030624/ .

-

SVG-MOBILE

-

Mobile SVG Profile: SVG Tiny, Version 1.2

, T. Capin, V. Hardy, O. Andersson, Editors, W3C Working Draft (work in progress), 13 August 2004, http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/WD-SVGMobile12-20040813/ . Latest version available at http://www.w3.org/TR/SVGMobile12/ .

-

SVG-TINY

-

Mobile SVG Profiles: SVG Tiny and SVG Basic