W3C Content Labels

W3C Incubator Group Report Draft 0.8 25 July 2006

- This version:

- http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/wcl/XGR-report-20060725/

- Previous version:

- http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/wcl/XGR-report-20060719/

- Latest version:

- http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/wcl/XGR-wcl/

- Authors:

- Phil Archer,

ICRA

- Jo Rabin,

Segala

Copyright © 2005 W3C ® (MIT, ERCIM,

Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C liability, trademark, document use

and software

licensing rules apply. Your interactions with this site are in accordance

with our public and

Member privacy

statements.

Abstract

A Content Label is a collection of metadata that can be applied to

multiple resources. An abstract model for how this can be achieved, how

resources can be grouped and how important details such as who created the

labels, when and under what circumstances they were created, is presented.

After publishing its report, the Content Label Incubator Group is seeking a

Working Group charter to develop the ideas further and work towards creating

a full W3C Recommendation.

Status of this document

This section describes the status of this document at the time of its

publication. Other documents may supersede this document. A list of Final Incubator Group Reports is available.

See also the W3C technical reports index

at http://www.w3.org/TR/.

This report is in a similar stage of development as a Working Group's

Working Draft. It is not final and any portion may be withdrawn or radically

altered. However, it reflects the current thinking within the XG and is

nearing completion.

This document was developed by the W3C Content Label

Incubator Group.

Publication of this document by W3C as part of the W3C Incubator Activity indicates

no endorsement of its content by W3C, nor that W3C has, is, or will be

allocating any resources to the issues addressed by it. Participation in

Incubator Groups and publication of Incubator Group Reports at the W3C site

are benefits of W3C

Membership.

The group was chartered

to look for "... a way of making any number of assertions about a resource or

group of resources." Furthermore "... those assertions should be testable in

some way through automated means."

It quickly became apparent that the terminology used in that summation

needed to be refined and clarified, however it was possible to construct a

set of use cases that amply demonstrate the aims in

more detail. A set of high level requirements was derived from the use cases

that were then formalized for this report.

Throughout the Incubator Activity, decisions have been taken via consensus

during regular telephone conferences and a face to face meeting. Discussion

of the requirements and what can and cannot be inferred from a content label

proving the most exhaustive. Based on that discussion it is possible to

reformulate the output of the Web Content Labels Incubator Activity as:

"A way of

making any number of assertions, using any number of vocabularies, about a

resource or group of resources. The assertions are open to automatic

authentication based on available data such as who made the assertions and

when."

We have deliberately taken a very broad approach so that it is possible

for both the resource creator and third parties to make assertions about all

kinds of things, with no architectural limits on the kind of thing they are

making claims about. For example, medical content labeling applications might

be concerned with properties of the agencies and processes that produce Web

content (e.g.. companies, people, and their credentials). By contrast, a

mobile content labeling application might be more concerned with different

kinds of information resource and their particular (and varying)

representations as streams of bytes. That said, we have focused on Web

resources rather than trying to define a universal labeling system for

objects.

The following report sets out the detailed requirements derived from the

original use cases and high level requirements (which are presented in the appendix). An abstract model; has been developed that

encapsulates the issues discussed and discovered during the XG's work.

Comments are also made on possible system architectures that can utilize

content labels as well as a detailed glossary.

The Incubator Group is now seeking a charter to reform as a full Working

Group on the W3C

Recommendation Track. It is believed that the work done to date is

substantial and has attracted significant support but there are some

outstanding issues that need to be addressed:

- The group believes that RDF is the most appropriate technology for

encoding content labels, however, this can be done in different ways.

Further, we recognize that there are alternative approaches and wish to

explore those as well. The expectation is that, if a WG is formed, it

will produce a normative RDF model along with sketches showing how the

abstract model might be encoded using other technologies. Further notes

are included on this aspect in the body of the report.

- What advantages, if any, do content labels offer over PICS? What, if any, are the

disadvantages? This issue has both policy and technology aspects that

need to be given full consideration before the withdrawal of PICS as a

Recommendation can be considered.

Carrying out these detailed and critical aspects of the WCL group's work

on the Recommendation Track will ensure full scrutiny by the wider community,

and enable greater interplay with, for example, the Mobile Web Best Practices

Group [MWBP], The Rule

Interchange Format WG [RIF] and

the Evaluation and Repair Tools Working Group [ERT].

Throughout this report, we use cLabel as a short-form of

content label.

The companies who participated in WCL-XG are as follows:

- Asemantics SRL *

- AT&T

- AOL Inc.

- Center for Democracy and Technology

- Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l'Europe

- Institute of Informatics & Telecommunications (IIT), NCSR*

- ILRT, University of Bristol*

- Internet Association of Japan

- Internet Content Rating Association (ICRA)*

- Maryland Information and Network Dynamics Lab at the University of

Maryland

- Opera Software

- RuleSpace LLC

- Segala*

- T-Online*

- Vodafone*

- Yahoo!*

* Original sponsor organization

The diverse membership reflects a widely recognized need to be able to

"label content" for various purposes. These range from child protection

through to scientific accuracy; from the identification of mobile-friendly

and/or accessible content, through to the linking of thematically-related

resources.

Based on the use cases and the original high

level requirements that were derived from them, a set of more detailed

requirements was established. These have been loosely categorized for easier

comprehension and care has been taken to use relevant terms as defined in the

glossary.

Fundementals

- It must be possible for both resource creators and third parties to

make assertions about information resources

- The assertions must be able to be expressed in terms chosen from

different vocabularies. Such vocabularies might include, but are not

limited to, those that describe a resource's suitability for children,

its conformance with accessibility guidelines and/or Mobile Web Best

Practice, its scientific accuracy and the editorial policy applied to its

creation. Existing vocabularies are preferred over newly defined ones

- It must be possible to group information resources and have cLabels

refer to that group of resources. For example, cLabels can refer to all

the pages of a Web site, defined sections of a Web site, or all resources

on multiple Web sites.

- A cLabel must be the expression of assertions made only by the party

that created it. It must not be necessary for assertions made by multiple

parties to be included in a single cLabel.

- cLabels must support a single composite assertion taking the place of a

number of other assertions. For example, WAI AAA can be

defined as WAI AA

plus a series of detailed descriptors. Other examples include mobileOK and

age-based classifications.

- More than one cLabel can refer to the same resource or group of

resources. Since conflicting labels are therefore permissible, the choice

of which label(s) to trust lies with the end user.

- It must be possible for a resource to refer to one or more cLabels. It

follows that there must be a linking mechanism between content and

labels.

- cLabels must be able to point to any resource(s) independently of those

resources.

- It must be possible to make assertions about cLabels using appropriate

vocabularies. For example, a cLabel can have metadata describing who

created it, what its period of validity is, how to provide feedback about

it, a who last verified it and when.

- It must be possible for a cLabel to be associated with its metadata and

vice versa.

- cLabels, metadata statements and individual assertions should have

unique and unambiguous identifiers.

Fitting in with commercial or other large scale workflows

- It must be possible for cLabels and cLabel metadata to be

authenticated.

- It must be possible to create and edit cLabels without modifying the

resources they describe.

- It must be possible to identify a default cLabel for a group of

resources and specify situations in which another cLabel overrides the

default. i.e. it must be possible to say "everything on example.com is

described by cLabel1 except resources in section A for which

cLabel2 applies."

Encoding labels for humans and machines

- It must be possible to express cLabels and cLabel metadata in a machine

readable way.

- The machine readable form of a cLabel and cLabel metadata must be

defined by a formal grammar

- cLabels must provide support for a human readable summary of the claims

it contains

- It must be possible to express cLabels and cLabel metadata in a compact

form

- Vocabularies and authentication data must be formally encoded and

support URI references

The requirements in the previous section can be expressed in a more

programmatic way as follows. A Content Label (cLabel) can carry a variety

statements such as:

cLabel {

That resource R has the property P1 is true

That resource R has Property P2 that has value V

That resource R meets WCAG 1.0 AA is true

That resource R was created in accordance with satisfactory procedures is

true

}

Where R may be either a single resource identified by its own URI or a

group of resources. Membership of a group R may be defined either by pattern

matching based on URIs or with reference to specified properties of

resources. The latter case includes, but is not limited to, properties such

as creation date, ISAN number etc.

Further, it is necessary to be able to make statements like:

metadata {

cLabel was created by $organization

{

has the e-mail address mail@organization.org

has a homepage at $url

has a feedback page at $URL

...

}

cLabel was created on $date

cLabel was last reviewed by $person

}

Finally, it is necessary to be able to send a real-time request to

$organization seeking automatic confirmation that it was responsible for

creating the cLabel, i.e. authenticating the label and the claims made. This

amounts to making statements like:

authentication {

metadata and cLabel verified by $organization

{ has email sss ... }

verified on $date}

Such a discussion leads us to the abstract model of cLabels as described

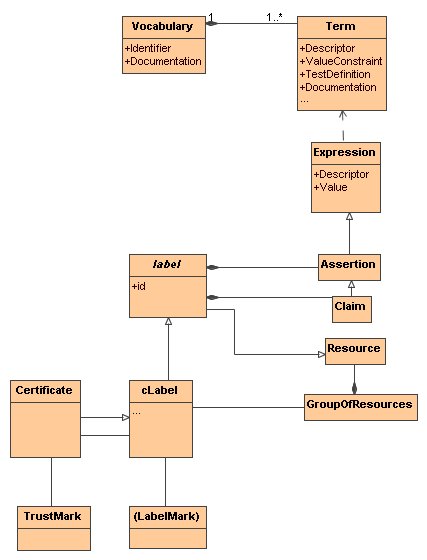

in figure 3.1 and the following text.

Figure 3.1 Schematic diagram of the abstratc model for

content labels.

A vocabulary collects together a number of related

properties or aspects of a resource that may be

useful in saying things about that resource. Those properties or aspects are

identified by terms of the vocabulary. Each term

is identified by a descriptor and may have

constraints placed on the values that are appropriate for use with that

descriptor. Further information may be associated with a descriptor such as

test suites for checking value assignment. The scope of use of the vocabulary

as a whole as well as the scope of individual terms may be noted. It is also

possible to assign vocabulary terms to a thematically-defined sub-group known

as a category.

An expression is a statement in respect of a

resource that the aspect of the resource denoted by a descriptor chosen from

a specific vocabulary has a certain value. A valid

expression makes reference to a vocabulary term that exists and whose chosen

value conforms to the constraints specified in the vocabulary.

An assertion is a specific type of expression

which is said to be true by the entity that makes it.

A claim is a specific type of assertion, whose veracity can be ascertained, either by reference to the

test conditions described in the relevant vocabulary term, or by observation

and interpretation of the meaning of the term as given in its scope notes.

A label is an abstraction, which is a specific type of resource and

contains assertions and claims in respect of a group of resources.

A cLabel is a specific type of label that has

assertions describing the circumstances of its creation and information about

the entity that created it. Assertions may be made about a cLabel in a certificate.

A cLabel for a given resource is identified by processing a Ruleset. This is associated with one or more cLabels by

direct inclusion of the cLabel within the Ruleset or by linkage. A Ruleset

MAY define the scope of the cLabels it is associated

with and MAY define a default cLabel for the

resources within its scope. A Ruleset MAY define rules

for applying a cLabel (other than the default, where defined) to a group of

resources within its scope. If the scope is not defined explicitly, then

processors MUST take the scope of the cLabels to be the set of resources that

links to the Ruleset or individual cLabels.

A cLabel SHOULD include a short text summary of

the assertions and claims in a form suitable for display to end users.

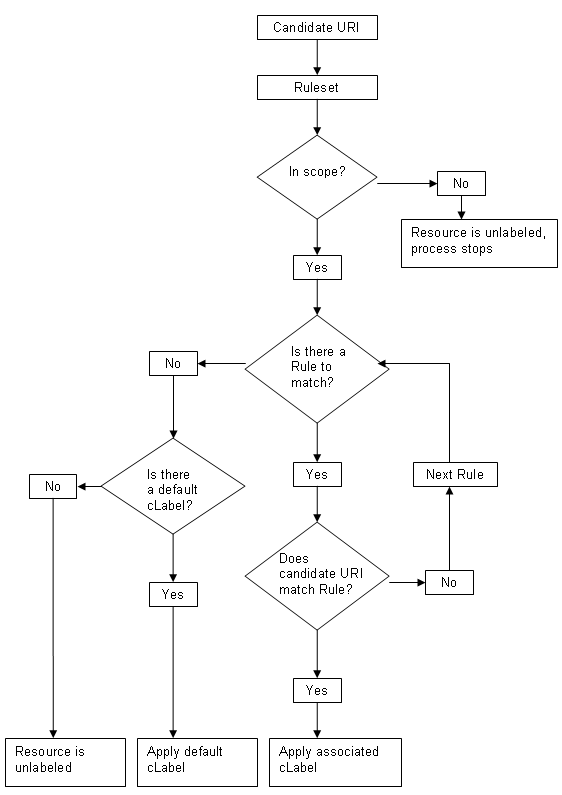

The processing model that follows from this is shown in figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 Diagrammatic representation of the WCL

processing model.

For a given resource, processing a Ruleset MUST return either 0 or 1

cLabels.

Multiple cLabels may be applied to a single resource either by including

one cLabel within another, or by linking a resource to multiple Rulesets.

The grouping of resources is a fundamental aspect of content labels and is

the subject of a separate paper [GROUP] that sets out

its own abstract model for this specific area. It allows a group to be

defined in such a way that it is programmatically possible to determine

whether a resource to be resolved from a URI is a member of that group. This

then makes it possible to identify the correct cLabel for the given

resource.

The creation of cLabels is usually done by people cf. the reading of

cLabels which is usually done by machines. Therefore it is important that

associating cLabels with groups of resources is a simple task with the burden

of processing of the data pushed to the client side. That said, processing of

cLabels may be done in real time as requests for resources are made.

Therefore the processing burden has been kept as light as possible to

minimize any latency caused by systems making use of cLabels.

As much from a policy perspective as a technical one, it is important that

the scope of a set of cLabels be clearly defined. At the topmost level this

means that it is possible to link a set of cLabels to one or more domains

since resources on those domains are either produced by the domain owner or

produced according to a set of policies set down by the domain owner.

Furthermore, simply-put policies such as:

- everything on my three domains except this bit has label A;

- unless told otherwise, everything on this domain has label B;

- the cLabel only applies to this group of things;

are all supported. The model allows groups of resources to be defined

through a list of domain names, with support for specific inclusion or

exclusion of sub-domains. Further intuitive support is provided for the

definition of sub-groups of resources available from those domains.

Group definitions are based primarily on pattern matching against URI

components: "everything with a path that starts with 'red'", for example.

However, this approach is not always practical. As a result, WCL also

supports the definition of groups based on properties of resources, through

simple lists of URIs and merely by a resource pointing to a cLabel.

Key aspects of group definition by URI and resource property are set out

in the following sub-sections. The two are not mutually exclusive: a group of

resources may be defined both in terms of URI patterns and resource

properties.

The abstract model for resource grouping uses terms taken primarily from

RFC 3986 with minor elaborations, and are illustrated in the following

example:

scheme://[userInfo@]host[:port][/path][?query][#fragment]

In addition, the term uri is defined to allow

matching against the entire URI without decomposition.

Modifiers

Aside from rules governing the normalization process of candidate URIs,

the matching process is controlled by a number of modifiers, as follows

(default values are given in the table below right):

|

match |

case |

| scheme |

exact |

insensititve |

| userInfo |

exact |

sensitive |

| host |

endsIn |

insensitive |

| port |

exact |

sensitive |

| path |

startsIn |

sensitive |

| query |

startsIn |

sensitive |

| fragment |

startsIn |

sensitive |

| uri |

regex |

sensitive |

Table: Defaults for Modifiers

- Match Type

- Exact, StartsIn, EndsIn (for leading and trailing character matching)

and Regex (if the match pattern is a regular expression)

- Case

- Controls whether the match is case sensitive or not

- Negate

- True if the result of the match is to be negated (default false)

Grouping, Inclusion and Exclusion

Within the abstract model, various facilities are provided for grouping

and for providing specific inclusion and exclusion from groups already

defined.

Encoding

The abstract model for resource grouping does not define an encoding, with

the specific intention that it may be encoded equally inter alia within an XML environment, an

RDF environment or some other environment. Different encodings are likely to

take varying approaches as to how they represent modifiers and inclusion and

exclusion.

An XML representation, such as the example given in [GROUP], might encode modifiers as attributes. Other

representations might choose to create data types by combining terms and

modifiers. host vs. exactHost for example.

When defining groups by resource properties, label creators MUST make the

data on the relevant properties available in such a way that the resource

itself does not need to be retrieved and parsed in order to determine whether

it is a member of the group or not. There are two reasons for this:

- It facilitates the creation of a generalized cLabel system that does

not need to be able to parse an unbounded number of types of

resource.

- It greatly increases efficiency.

The precise property or properties used to define the group will be

determined by the label creator. The values of the properties SHOULD be made

available either as a database retrievable from a given URI in a given

format, or from a given URI using a given protocol.

Should WCL-XG be successful in securing a WG charter, the abstract model

for resource grouping will itself come under full scrutiny with a view to its

publication either as a WG Note or a full Recommendation in its own right.

Resources SHOULD be linked to labels using either the HTML Link element or

its HTTP Response header equivalent [MNOTT]. If

successful in securing a WG charter, WCL intends to provide a metadata

profile that will define a link relationship of cLabel. An example of this is

available now at http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/wcl/meta-profile/,

and could be included as a value for the profile attribute [PROFILE] of the head element of an (X)HTML document that

is linked to cLabels.

The hyperlink reference MUST be to one of the following:

- the URI of the data source where a query for the WCL Ruleset will

return a single data point;

- the URI of a Ruleset, typically identified by a URI fragment;

- a specific cLabel, typically identified by a URI fragment.

Example: cLabels for all resources on the example.com domain are provided

in an RDF instance with a single Ruleset.

XHTML link tag:

<link rel="cLabel"

href="http://example.com/clabels.rdf" type="application/rdf+xml"

/>

Equivalent HTTP Response Header

Link: </clabels.rdf>; /="/"; rel="cLabel"

type="application/rdf+xml";

If the data includes more than one Ruleset, it is necessary to identify

which Ruleset applies by adding the ID of the required Ruleset to the

hyperlink reference URI as a fragment identifier.

Example: cLabels for all resources on the example.com domain are provided

in an RDF instance with multiple Rulesets encoded as named graphs.

XHTML link tag:

<link rel="cLabel"

href="http://example.com/clabels.rdf#ruleset_1" type="application/rdf+xml"

/>

Equivalent HTTP Response Header

Link: </clabels.rdf#ruleset_1>; /="/"; rel="cLabel"

type="application/rdf+xml";

Linking from a resource directly to a specific cLabel needs further

examination. It is anticipated that this will be useful to content providers

as an easy method to override the default cLabel identified by the Ruleset.

For example, a content provider may label all content on their domain as

being child-friendly by default. This can be done through configuring the

server to include an HTTP Response Header pointing to a data file or Ruleset

that in turn defines the default cLabel. When creating an individual page,

however, the content provider may include a link to a different cLabel

warning of material that may not be suitable for children. This link

overrides the default label.

Clients MUST, however, attempt to establish any scope restrictions on the

cLabel. This can be done by:

- removing the fragment identifier from the link to the cLabel;

- querying the data for a Ruleset;

- checking for scope restrictions and matching against the labeled

resource.

If the resource is within the defined scope, the cLabel MUST be applied,

overriding any default. If the resource is out of scope, the cLabel MUST be

ignored. If no scope is defined, or it is not possible to determine whether

scope is defined or not, then the client MAY apply the cLabel.

The abstract model presented in the previous section implies or calls

directly for a number of vocabulary terms. For convenience, these are given

below under a number of category headings.

- Category

- Defined in the glossary

- Descriptor

- Defined in the glossary

These can be used in addition to whatever descriptive vocabulary or

vocabularies are used.

- cLabel

- Defined in the glossary

- Ruleset

- Defined in the glossary

- Scope

- Defined in the glossary

- Default Label

- Defined in the glossary

- Rule

- Defined in the glossary

- Summary

- Defined in the glossary

- Include

- Allows one cLabel to include another. A semantically

more accurate term would be "is also described by" but "include" is

more intuitive

- Classification

- A link to a classification that MAY be further decomposed into atomic

statements.

- Last reviewed

- The date on which the labeled resources were last

reviewed. This is a specialization of the Dublin Core Date element and SHOULD be expressed in the W3C date

& time format [W3CDTF].

- Reviewed by

- The individual who reviewed the resource and verified

the claims made in the cLabel.

- Approved

- The individual who checked the reviewer's verification

of the claims made in the label.

- Valid until

- The date until which the cLabel or certificate SHOULD

be treated as valid. This is a specialization of the Dublin Core Date element and SHOULD be expressed in the W3C date

& time format [W3CDTF].

- Withdrawn

- The date on which the cLabel creator or certification

authority withdrew the cLabel or certificate. This is a specialization

of the Dublin Core Date element and SHOULD be

expressed in the W3C date & time format [W3CDTF].

- Test Result

- A link to a test results, such as an EARL

assertion.

NB: The Dublin Core Term Issued

SHOULD be used to declare when a cLabel or certificate was issued (the DC

Term 'Created' is more suited as a descriptor for when the labeled resource

was created). As with the WCL descriptors 'Last reviewed', 'Valid until' and

'Wthdrawn', DC Terms 'Issued' is a specialization of the Dublin Core Date

element and SHOULD be expressed in the W3C date & time format [W3CDTF].

Any amount of such data can usefully be provided using existing

vocabularies such as FOAF, Dublin Core and vCard, and we have listed those

that an LA can reasonably be expected to provide. We have further defined a

series of terms that SHOULD be provided by LAs (where applicable) and SHOULD

be utilized by clients.

4.4.1 Terms from FOAF

- Organization

- Use this as the placeholder for terms describing the

organization or individual that created the labels

- name

- Use this to give the full name of the LA

- homepage

- The URI of the homepage of the LA

- mbox

- The LA's primary e-mail address

- Description

- A short description of the LA and its work. For WCL

purposes, this SHOULD be limited to 400 characters, Use a term such as

RDF's See Also to provide a more detailed description.

- Subject

- A brief text description of the subject(s) covered by the labels.

Typically this will be in the form of keywords

4.4.3 Terms from vCard

- Address (ADR)

- vCard defines the following terms for postal addresses.

- Street

- Locality

- Post Code (Pcode)

- Country

- Voice

- The (voice) phone number

- Fax

- The LA's fax number (if applicable)

- Shortname

- The acronym or short name for the LA

- Authority for

- A namespace of for a vocabulary for which the label

creator is an authority. The element can be occur any number of times

to declare multiple vocabulary namespaces

- icon

- A 16 x 16 pixel logo for the LA. This must be in either

gif or png format

- Public PGP key

- The LA's public Key (if applicable)

- Public digital certificate

- The LA's public digital certificate (if applicable)

The 'Authority for' term is provided because although it is usual for an

LA to issue labels from its own vocabulary, it may wish to include other

vocabularies as well. Furthermore, additional vocabularies may be included in

cLabels by the content provider or others and this term enables an LA to

specify exactly for which descriptions it is and is not responsible.

As defined in the glossary, a content label is a

set of assertions made using one or more vocabularies to describe a resource

or group of resources. In turn, an assertion is an expression that is claimed

to be true.

It follows that a cLabel SHOULD be taken as the expression of an opinion

held by an individual, organization or automaton at a particular point in

time. It cannot be taken as proof, in a logical sense, that one or more of

the assertions expressed in the cLabel is true as an empirical fact.

Furthermore, the content label is limited by the vocabularies used. That

is, clients MUST NOT make any inference about a resource or group or

resources based on the absence of any descriptor. To give a simple example of

this. if a content label describes a resource solely in terms of its color,

no inference can be drawn about its shape.

Content Labels can be used in a variety of systems and it is not the XG's

intention to define a single architecture. However. we do recommend that the

following elements are present in any complete system.

- Content Labels served either from the labeled site or from a labeling

authority

- Metadata about a given cLabel giving detail of who created it, when,

its period of validity and so on (see WCL

Vocabulary)

- An authentication route through which a client can make an automated

request to the LA

- An API through which an LA makes available labels for a given

resource

- An API though which an LA makes all its labels available as a single

download

These elements can be combined in any number of ways, some of which are

highlighted in the following sections.

The Quatro project, co-funded by the European Union

[SIP], combines the elements listed above into a basic

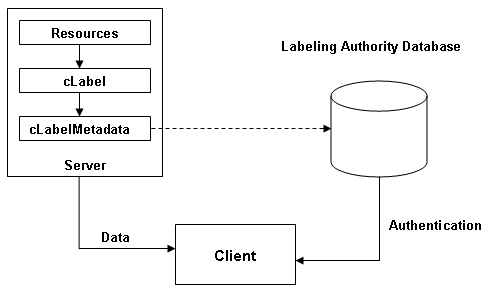

architecture with 3 variations. In all cases, content is linked to the cLabel

and the cLabelMetadata points to the Labeling Authority.

It should be noted that although every resource must be linked to the

cLabel in this model, a client seeking that cLabel will only have to retrieve

it once. After the data has been retrieved, whether from the labeled site or

the LA database, no further network request is required for as long as the

cLabel is held in cache by the client.

Fig 6.1 Diagrammatic representation of simple architecture

in which data about resources is held on the same server as those resources.

The cLabelMetadata provides a link to the LA which is able to authenticate

the data.

Labels are hosted near to the resources they describe (typically the same

website) and the LA's database supplies simple authentication. Since in this

model content providers are allowed to edit their label to reflect changes in

their content, the cLabel may not be exactly the same as the one issued.

However the LA is able to assert that it trusts the content provider to make

such changes faithfully.

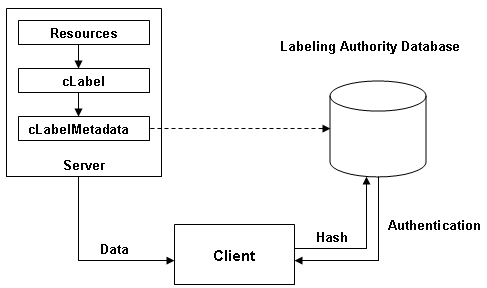

Fig 5.2 Diagrammatic representation of simple architecture

in which data about resources is held on the same server as those resources.

A hash of this data is sent to the LA (identified in the cLabelMetadata)

which is then is able to authenticate the data by comparing it with the hash

stored in its database.

This is similar to the previous model but differs in the important respect

that the LA does not allow content providers to edit their cLabels. Therefore

a hash of the label can be checked against data held by the LA to ensure

label integrity.

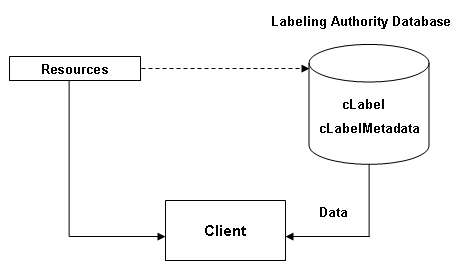

Fig 6.3 Diagrammatic representation of architecture in

which all cLabel data is held by the Labeling Authority.

In this architecture, cLabels are delivered directly from the LA's

database. Therefore there is no possibility for the label to be modified by

the content provider and the source of the labels carries greater inherent

trust. On the downside, this model places greater demands on the server

infrastructure, system integration and bandwidth usage by the LA.

The 3 variants of the Quatro architecture above all show a linkage between

the content and the cLabel and a link from the cLabelMetadata to the LA. It

is possible to create and use cLabels independently of such links.

An important point to note in this regard is that cLabels, like the

resources they describe, have URIs. A certification authority could add its

own certificate to the architecture shown in figures 5.1. and 5.2; likewise a

client might be configured to seek cLabels from an independent organization's

database without following links from the content itself.

The issue of trust is a key issue for the Semantic Web and several

relevant models have been proposed. Any of these could potentially apply

here, especially if cLabels are encoded in RDF.

For example, TriQL.P

is a query language that allows trust to be evaluated by comparing data drawn

from different sources. In the WCL context one might see this working by

querying cLabels from different sources describing the same group of URIs.

The University of Maryland's Trust

Project looks at ways of building trust on the Web using shared personal

movie ratings, shared contacts files etc.

W3C's Annotea project offers

mechanisms for sharing annotations and bookmarks - ideas that find expression

in things like social network sites and bookmark sharing systems. These

networks can readily be leveraged to add trust to, and make use of, cLabels

in a variety of ways.

As noted throughout this report, the group is seeking a Working Group

charter and believes that this is the correct forum in which to define a

normative encoding for cLabels. It is anticipated that the primary encoding

will be in RDF but that alternatives will be considered. For example,

extensions for RSS and ATOM to allow a default cLabel to

be declared at the channel/feed level with overriding cLabels at item/entry

level.

Several XG members have experience of working with a system that has not

been fully standardized known as RDF Content Labels [RDF-CL]. Until and if a WG charter is secured, this method

remains adequate, practical and meets a great many of the use cases

and requirements set out by the XG. However, it is not a full

encoding of the WCL abstract model, differing in the following respects:

- RDF-CL seeks to limit the number of labels that can apply to a given

resource to 1 (WCL allows any number).

- RDF-CL has a much more limited mechanism for defining groups of

resources than is set out in this report and its companion document.

- RDF-CL offers parallel systems for providing labels, classifications

and management information (creator, rights holder etc.). This has the

potential to cause unnecessary confusion.

- RDF-CL has some native support for labeling of movies and video games,

but seeks to restrict the way this is done to a particular paradigm that

is relatively inflexible. The issues are probably better handled through

extensions to the WCL model.

Work has been done within the XG looking at how RDF-CL, and therefore a

future RDF encoding of WCL, might be used in other circumstances.

For example, could content labels be developed as a microformat? Possibly,

however, the lack of namespaces leaves open the possibility of confusion over

common words and terms being used to describe content in different

vocabularies/schemata.

RDFa has real potential since it lets us annotate

XHTML documents with classes and properties from RDF vocabularies using

namespaces and Qnames as in any xml document. There are two options to

describe content with RDFa. Either use RDFa annotations in the XHTML

document/resource as class names and inject namespaces as needed, or link

from the document/resource to another XHTML document that contains the human

representation of the labels (readable using any browser) and annotate the

XHTML elements (div , span) with RDF class names and properties. In both

cases GRDDL could be used to transform the XHTML

instance to RDF that could be then queried using SPARQL. The first case covers the issues of defining

groups.

The group also considered whether it would be feasible to treat an RDF-CL

instance as XML (assuming the RDF were serialized in XML). This is certainly

possible in that XSLT transforms were successfully carried out. However, it

was a very fragile system that depended on the data being presented according

to a particular structure. It is not suitable as a long term strategy.

If successful in securing a WG charter, WCL would seek to:

- Produce a normative encoding of the WCL abstract model in RDF. This

would, of course, take into account any changes made to the abstract

model made by the WG itself. The discussion would be likely to include

sample SPARQL queries etc. and guidance on making data available for property-based resource grouping.

- Show examples of cLabels encoded using RDFa.

- At least a sketch for encoding cLabels entirely in XML.

The following terms are used throughout this report. Definitions have been

collected from W3C glossaries

where possible and provided a priori where necessary.

Assertion Any expression which

is claimed to be true. [W3C definition

source]

Authenticate, (n.

authentication) To provide evidence that assertions made in a cLabel, cLabel

metadata or a certificate are the

authentic view of the entity that created them. Such evidence will typically

be acquired by direct communication with that entity.

Category A thematically-related

sub-group of terms within a vocabulary.

Certificate A cLabel containing assertions about the veracity of claims made in another cLabel.

Certification The process

of verification of claims and the creation of a certificate.

Claim An assertion whose truth can be assessed by an

independent party.

Content Label, cLabel A set of

assertions made using one or more vocabularies

to describe a resource or group of

resources.

Content provider An

entity (individual, organization or automaton) that provides resources in response to requests, whether or not

the resource was created by that entity.

Default cLabel The cLabel that should be applied to any resource within the scope of a Ruleset in

the absence of a rule to the contrary.

Descriptor An aspect of a

resource about which it is possible to make

assertions. For example, color, size and

shape. A descriptor becomes a vocabulary term

when it is associated with possible values.

Expression An instance of a

vocabulary term and its value.

Information resource A resource which has the property that all of its

essential characteristics can be conveyed in a message. [W3C

definition source]

Labeling Authority (acronym LA) An

organization that provides infrastructure for the generation and

authentication of content labels.

Resource Anything that might be

identified by a URI. [W3C

definition source]

Resource creator The

individual or organization that created the resource.

Rule In the specific context of WCL,

a rule defines a group of resources and a

cLabel that applies to all resources in that

group.

Ruleset A block of data that can

be processed to determine which of a set of cLabels, if any, should be applied to a given resource.

Schema (pl., schemata) A document

that describes an XML or RDF vocabulary. Any document which describes, in a

formal way, a language or parameters of a language.[ W3C

definition source]

Scope The set to which a resource must belong if any cLabel included within or linked from a Ruleset is to be applied.

Summary A short summary of the

description provided of the resource by the

cLabel, suitable for display to end users.

Trustmark A sign (machine

processable and/or human perceivable) that a certificate has been issued.

Valid A cLabel is valid if it has

an associated schema or schemata and if it complies with the constraints

expressed therein. [Adapted W3C

definition]

Verification The process of

assessing the correctness of claims.

Vocabulary A collection of vocabulary terms, usually linked to a document that

defines the precise meaning of the descriptors

and the domain in which the vocabulary is expected to be used. When

associated with a schema, attributes are

expressed as URI references. [This definition is an amalgam of those provided

in Composite

Capability/Preference Profiles (CC/PP): Structure and Vocabularies 1.0

and OWL Web

Ontology Language Guide.]

Vocabulary term An attribute

that can describe one or more resources using

a defined set of values or data type. Attributes may be expressed as a URI

reference. See also descriptor and expression.

Well-formed Syntactically

legal. [W3C

definition source]

The editors acknowledge significant contributions from:

- Kal Ahmed, Techquila

- Dan Appelquist, Vodafone Group Services

- Dan Brickley

- Kendall Clark

- Kjetil Kjernsmo, Opera Software

- Pantelis Nasikas, Institute of Informatics & Telecommunications

(IIT), NCSR

- Diana Pentecost, AOL Inc.

- Dave Rooks, Segala

- Kai-Dietrich Scheppe, T-Online

The use cases

Use Case 1: Profile matching

The original use case given in the charter

has been simplified by reducing the number of essential actors to three:

- CONTENT PROVIDER (metadata provider)

- PORTAL PROVIDER (metadata consumer)

- END USER

One can imagine a range of scenarios with very similar characteristics

that amount to "sub-use cases."

Sub use case 1A: END USER discovers content appropriate to their device

["MobileOK"]

Fig 1. Diagrammatic version of

sub-use case 1A.

- END USER visits portal

- END USER's device profile is extracted with reference to a separate

metadata store

- END USER searches for a topic of interest.

- PORTAL PROVIDER matches END USER's device profile with contentprofiles

provided by CONTENT PROVIDER.

- PORTAL PROVIDER provides search results matching this topic.

- PORTAL PROVIDER filters results based on the metadata encoded in the

content with regard to the "mobile friendliness" of the

content/presentation in question and the known properties of the device

profile according to business rules.

Sub use-case B: END USER discovers content appropriate to their age-group

["Child Protection"]

Fig 2. Diagrammatic version of

sub-use case 1B.

- END USER visits portal

- END USER's user profile is extracted from a repository, perhaps the

portal's own.

- END USER searches for a topic of interest.

- PORTAL PROVIDER matches END USER's age with content profiles provided

by CONTENT PROVIDER.

- PORTAL PROVIDER provides search results matching this topic.

- PORTAL PROVIDER filters results based on the metadata encoded in the

content with regard to the "child friendliness" of the

content/presentation in question and the known age of the user according

to local business rules.

The Example Trustmark Scheme reviews online traders, providing a trustmark

for those that meet a set of published criteria. The scheme operator wishes

to make its trustmark available as machine readable code as well as a graphic

so that content aggregators, search engines and end-user tools can recognize

and process them in some way.

The trustmark operator maintains a database of sites it has approved and

makes this available in two ways:

First, the labelled site includes a link to the database. This can be

achieved in a variety of ways such as an XHTML Link tag, an HTTP Response

Header or even a digital watermark in an image. A user agent visiting the

site detects and follows the link to the trustmark scheme's database from

which it can extract the description of the particular site in real time.

Secondly, the scheme operator makes the full database available in a

single file for download and processing offline.

Since the actual data comes directly from the trustmark scheme operator,

it is not open to corruption by the online trader and can therefore be

considered trustworthy to a large degree. To reduce the risk of spoofing,

however, the data is digitally signed.

Mrs Chaplin teaches 7 year olds at her local school. An IT enthusiast, she

makes her teaching materials available through her personal website. She adds

metadata to her material that describes the subject matter and curriculum

area. In order to gain wider trust in her work she submits her site for

review by her local education authority and a trustmark scheme. Both

reviewers offer Mrs Chaplin a digitally signed, machine-readable version of

their trustmark that she can add to her site. She merges these into a single

pool of metadata to which she adds content descriptors from a recognized

vocabulary that declare the site to contain no sex or violent content. She

adds her own digital signature to the metadata. The set of digital signatures

allow user-agents to identify the origin of the various assertions made. As

in use case 2, links from the content itself point to this metadata.

Since the metadata is on the website itself, user agents are unlikely to

take the assertions made in the metadata at face value. Unlike the trustmark

operator, the local authority does not operate a web service that can support

the label, it does, however, digitally sign its labels and publishes its

public key on its website. This can be used to verify that it is indeed the

local education authority that issued the relevant data in the label.

Separately, a user-agent can interrogate the trustmark operator's database

in real time to check whether Mrs Chaplin is authorized to make the

assertions relevant to their namespace. Furthermore, the use of a recognized

vocabulary for the content description means that a content analyser trained

to work with that vocabulary can give a probabilistic assessment of the

accuracy of the relevant data.

Taken together, these multiple sources of data can provide confidence in

the quality of the content and the local authority trustmark which is not

directly testable. The multiple data sources may be further supported by

recognising that Mrs Chaplin's work is cited in many online bookmarks, blog

entries and postings to education-related message boards.

Dave Cook's website offers reviews of children's films and the site is

summarized in both RSS and ATOM feeds. Most of the films reviewed have an

MPAA rating of G and/or British Board of Film Classification rating of U.

This is declared in a rating for the channel as a whole. However, Dave

includes reviews of some films rated PG-13 or 12 respectively which is

declared at the item level and overrides the channel level metadata.

The actual rating information comes from an online service operated by the

relevant film classification board itself and is identified using a URL and

human-readable text. The movie itself is identified by either an ISAN number or the relevant Internet Movie

Database entry ID number. As with use case 2, trust is implicit given the

source of the data, which is indicated by a link to Dave's site's policy.

Separately, Fred combines Dave Cook's and other review feeds to provide

alternative reviews of the movies by transforming the ATOM feeds into RDF and

creating an aggregate view using SPARQL queries.

Fred operates an antiracism education site which aggregates and curates

content from around the Web. Fred wants to label the resources that he

aggregates such that educational and other institutions may harvest the

resources and associated commentary and metadata automatically for reuse

within their instructional support systems, etc.

One of the ways in which Fred wants to curate resources is to say about

them that they are pedagogically useful but politically noxious. For example,

some sites on the Web make claims about Martin Luther King, Jr that are

motivated by a racist ideology and are historically indefensible. Fred's

vocabulary allows him to claim that such resources are pedagogically useful

for purposes of analysis, but that they are otherwise suspicious and should

only be consumed by students in an age-appropriate manner or with appropriate

supervision, etc. In other words, Fred needs to be able to make sharply

divergent claims about resources: (1) that they are noteworthy, and (2) that

they are, from his perspective, dangerous or noxious or troublesome.

A company named Advance Medical Inc. reviews medical literature on the Web

based on a range of quality criteria such as effectiveness and research

evidence. The criteria may be changed according to current scientific and

professional developments. The review process leads to literature being

classified as belonging to one of 5 levels as follows.

- Level A : clear evidence.

- Level B : supportive evidence.

- Level C : poor evidence.

- Level D : expert opinion with explicit critical appraisal.

- Level E : no evidence.

The company produces label data that declares the classification level

value and provides a summary of each document. The label data is stored in a

metadata repository which can be accessed via the Web.

M.D. Smith uses the label data in the repository to make decisions about

heath care for specific clinical circumstances.

Requirements

The following requirements have been approved by the group.

- It must be possible to group resources and to make assertions that

apply to the group as a whole (This is fundamental to all use cases)

- It must be possible to self-label (use cases 2 - 4)

- To provide as complete a description as possible, labels must be able

to contain unambiguous assertions using more than one vocabulary (all use

cases, especially 3)

- It must be possible for a content provider to make reference to third

party labels (use case 2)

- It must be possible to make assertions about the accuracy of claims

made in a label (use case 2)

- The system must be readily usable within a commercial workflow,

allowing a content provider to apply metadata to a large number of

resources in one step and to separate the activity of labelling from that

of content creation, where desired (use case 1).

- The system must support a concept of default and override metadata. The

mechanism that is used to determine where overrides apply should be based

on the full concept of a URI rather than, for example, just a web URL.

(Use case 1, 2, 4)

- It should be possible to ascertain unambiguously who created the label,

using techniques such as digital signatures, S/MIME etc. (use cases 2, 3

and perhaps 5)

- It must be possible for a labeling organization to make all its labels

available as a single database (use case 2)

- It should be possible to include assertions from an unlimited number of

vocabularies in a single content label. Assertions from each vocabulary

may be subject to its own verification mechanism (use case 3)

- Labels should support a human-readable summary as well as the

machine-readable code (all).

- Labels should validate to formal published grammars (all)

- It must be possible to encode labels in a compact/efficient form

(all)

- It must be possible to identify whether labels are self-applied or

created by a third party. (use case 2)

- It must be possible to discover a feedback mechanism for reporting

false claims (all, especially use case 2)

- It must be possible to associate labels with a 'time to live' and/or

'expiry date' (all, especially user case 2)

- It must be possible to discover the date and time when a label was last

verified and by whom. (all, especially use case 2)

- It must be possible to describe the process by which data in labels is

to be verified (use case 3)

Although not a testable requirement, the group has further resolved the

principle that adding labels to resources should be easy and intuitive. It is

recognized that this is likely to be made so through implementation but the

design of the system should nonetheless be mindful of the principle (use case

3).