This section of the document describes in depth the need for language and direction metadata and various use cases helpful in understanding the best practices and alternatives listed above.

3.1 Identifying the Language of Content

3.1.1 Definitions

Language metadata typically indicates the

intended linguistic audience or user of the resource as a whole, and

it's possible to imagine that this could, for a multilingual resource,

involve a property value that is a list of languages. A property that

is about language metadata may have more than one value, since it aims

to describe all potential users of the information

The text-processing language is the language of a

particular range of text (which could be a whole resource or just part

of it). A property that represents the text-processing language needs

to have a single value, because it describes the text content in such a

way that tools such as spell-checkers, default font applicators,

hyphenation and line breakers, case converters, voice browsers, and

other language-sensitive applications know which set of rules or

resources to apply to a specific range of text. Such applications

generally need an unambiguous statement about the language they are

working on.

3.1.2 Language Tagging Use Cases

Kensuke is reading an old Tibetan manuscript from the Dunhuang

collection. The tool he is using to read the manuscript has access

to annotations created by scholars working in the various languages

of the International Dunhuang Project, who are commenting on the

text. The section of the manuscript he is currently looking at has

commentaries by people writing in Chinese, Japanese, and Russian.

Each of these commentaries is stored in a separate annotation, but

the annotations point to the same point in the target document.

Each commentary is mainly written in the language of the scholar,

but may contain excerpts from the manuscript and other sources

written in Tibetan as well quoted text in Chinese and English. Some

commentaries may contain parallel annotations, each in a different

language. For example, there are some with the same text translated

into Japanese, Chinese and Tibetan.

Kensuke speaks Japanese, so he generally wants to be presented with the

Japanese commentary.

The annotations containing the Japanese commentary have a language property set to "ja" (Japanese). The tool he is using knows that he wants to read the Japanese commentaries, and it uses this information to select and present to him the text contained in that body. This is language information being used as metadata about the intended audience – it indicates to the application doing the retrieval that the intended consumer of the information wants Japanese.

Some of the annotations contain text in more than one language.

For example, there are several with commentary in Chinese, Japanese

and Tibetan. For these annotations, it's appropriate to set the

language property to

"ja,zh,bo" –

indicating that both Japanese and Chinese readers may want to find

it.

The language tagging that is happening here is likely to

be at the resource level, rather than the string level. It's

possible, however, that the text-processing language for strings

inside the resource may be assumed by looking at the resource level

language tag – but only if it is a single language tag. If the tag

contains "ja,zh,bo" it's not clear which strings are in

Japanese, which are in Chinese, and which are in Tibetan.

3.1.2.2 Capturing the text-processing language

Having identified the relevant annotation text to present to

Kensuke, his application has to then display it so that he can read it.

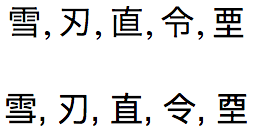

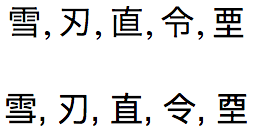

It's important to apply the correct font to the text. In the following

example, the first line is labeled ja

(Japanese), and the second zh-Hant (Traditional

Chinese) respectively. The characters on both lines are the same code points, but they demonstrate systematic differences between how those and similar codepoints are rendered in Japanese vs. Chinese fonts. It's important to associate the right forms with the right language, otherwise you can make the reader uncomfortable or possibly unhappy.

So, it's important to apply a Japanese font to

the Japanese text that Kensuke is reading. There are also

language-specific differences in the way text is wrapped at the end

of a line. For these reasons we need to identify the actual

language of the text to which the font or the wrapping algorithm

will be applied.

Another consideration that might apply is the use of

text-to-speech. A voice browser will need to know whether to use

Japanese or Chinese pronunciations, voices, and dictionaries for the ideographic characters

contained in the annotation body text.

Various other text rendering or analysis tools need to know

the language of the text they are dealing with. Many different types of text processing depend on information about the language of the content in order to provide the proper processing or results and this goes beyond mere presentation of the text. For example, if Kensuke wanted to search for an annotation, the application might provide a full text search capability. In order to index the words in the annotations, the application would need to split the text according to word boundaries. In Japanese and Chinese, which do not use spaces in-between words, this often involves using dictionaries and heuristics that are language specific.

We also need a way to indicate the change of language to Chinese and

Tibetan later in the commentary for some annotations, so that

appropriate fonts and wrapping algorithms can be applied there.

3.1.2.3 Additional Requirements for Localization

Having viewed the commentaries he is interested in, Kensuke realizes that he needs another reference work, but he's not sure of the catalog number. He uses an application for searching out catalog entries. This application is written in JavaScript and can be switched between several languages, according to the user preference. One way to accomplish this would be to reload the application's user interface from the server each time the user selects a new language. However, because this application is relatively small, the developer has elected to package all of the translations with the JavaScript (there are several open source projects that allow runtime selection of locale). Similarly, the catalog search service sends records back in all of the available languages, rather than pre-selecting according to the user's current language preference.

The original example shows a data record available in a single language. But some applications, such as the catalog search tool and its supporting service, might need the ability to send multiple languages for the same field, such as when localizing an application or when multilingual data is available. This is particularly true in cases like this, when the producer needs to support consumers that perform their own language negotiation or when the consumer cannot know which language or languages will be selected for display.

Serialization agreements to support this therefore need to represent several different language variations of the same field. For instance, in the example above the values title or description might each have translations available for display to users who speak a language other than English. Or an application might have localized strings that the consumer can select at runtime. In some cases, all language variations might be shown to the user. In other cases, the different language values might be matched to user preferences as part of language negotiation to select the most appropriate language to show.

When multiple language representations are possible, a serialization might provide a means (defined in the specification for that document format) for setting a default value for language or direction for the whole of the document. This allows the serialized document to omit language and direction metadata from individual fields in cases where they match the default.

3.2 Identifying the Base Direction of Content

In order for a consumer to correctly display bidirectional text, such as those in the following use cases, there must be a way for the consumer to determine the required base direction for each string. It is not enough to rely on the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm to solve these issues. What is needed is a way to establish the overall directional context in which the string will be displayed (which is what 'base direction' means).

These use cases illustrate situations where a failure to apply the necessary base direction creates a problem.

3.2.1 Final punctuation

This use case consists of a string containing Hebrew text followed by punctuation – in this case an exclamation mark. The characters in this string are shown here in the order in which they are stored in memory.

"בינלאומי!"

If the string is dropped into a LTR context, it will display like this, which is incorrect – the exclamation mark is on the wrong side:

Result: "בינלאומי!"

Dropped into a RTL context, this will be the result, which is correct:

תוצאה: "בינלאומי!"

The Hebrew characters are automatically displayed right-to-left by applying the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm (UBA). However, in a LTR context the UBA cannot make the exclamation mark appear to the left of the Hebrew text, where it belongs, unless the base direction is set to RTL around the inserted string.

In HTML this can be done by inserting the string into a dir attribute with the value rtl. That yields the following:

Result: "בינלאומי!"

3.2.2 Initial Latin

In this case the Hebrew word is preceded by some Latin text (such as a hashtag). The characters in the order in which they are stored in memory.

"bidi בינלאומי"

If the string is dropped into a LTR context, it will display like this, which is incorrect – the word 'bidi' should be to the right:

bidi בינלאומי

Dropped into a RTL context, this will be the result, which is correct:

bidi בינלאומי

The Hebrew characters are reversed by applying the Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm (UBA). However, in a LTR context the UBA cannot make the 'bidi' word appear to the right of the Hebrew text, where it belongs, unless the base direction is set to RTL around it.

Notice how our original example demonstrates this. The title of the book was displayed in an LTR context like this:

Title: HTML و CSS: تصميم و إنشاء مواقع الويب

However, the title is not displayed properly. The first word in the title is "HTML" and it should show on the right side, like this:

Title: HTML و CSS: تصميم و إنشاء مواقع الويب

This has an additional complication. Often, applications will test the first strong character in the string in order to guess the base direction that needs to be applied. In this case, that heuristic will produce the wrong result.

The example that follows is in a RTL context, but the injected string has been given a base direction based on the first strong directional character, and again the words 'HTML' and 'CSS' `are in the wrong place.

عنوان كتاب: HTML و CSS: تصميم و إنشاء مواقع الويب

3.2.3 Bidirectional text ordering

In this case the string contains three words with different directional properties. Here are the characters in the order in which they are stored in memory.

"one שתיים three"

If the string is dropped into a LTR context, it will display like this:

one שתיים three

Dropped into a RTL context, this will be the result – the order of the items has changed:

one שתיים three

If a bidirectional string is inserted into a LTR context without specifying the RTL base direction for the inserted string, it can produce unreadable text. This is an example.

Translation is: "في XHMTL 1.0 يتم تحقيق ذلك بإضافة العنصر المضمن bdo."

What you should have seen is:

Translation is: "في XHMTL 1.0 يتم تحقيق ذلك بإضافة العنصر المضمن bdo."

This can be much worse when combined with punctuation, or in this case markup. Take the following example of source code, presented to a user in an educational context in a RTL page: <span>one שתיים three</span>. If the base direction of the string is not specified as LTR, you will see the result below.

<span>one שתיים three</span>

(This happens because the Unicode bidi algorithm sees span>one as a single directional run, and three</span as another. The outermost angle brackets are balanced by the algorithm.)

3.2.4 Interpreted HTML

The characters in this string are shown in the order in which they are stored in memory.

"<span dir='ltr'>one שתיים three</span>"

This use case is for applications that will parse the string and convert any HTML markup to the DOM. In this case, the text should be rendered correctly in an HTML context because the dir attribute indicates the base direction to be applied within the markup. (It also applies bidi isolation to the text in browsers that fully support bidi markup, avoiding any spill-over effects.) It relies, however, on a system where the consumer expects to receive HTML, and knows how to handle bidi markup.

It also requires the producer to take explicit action to identify the appropriate base direction and set up the required markup to indicate that.

3.2.5 Neutral LTR text

The text in this use case could be a phone number, product catalogue number, mac address, etc. The characters in this string are shown in the order in which they are stored in memory.

"123 456 789"

If the string is dropped into a LTR context, it will display like this, which is correct:

123 456 789

Dropped into a RTL context, this will be the result, which is incorrect – the sequencing is wrong, and this may not even be apparent to the reader:

123 456 789

When presented to a user, the order of the numbers must remain the same even when the directional context of the surrounding text is RTL. There are no strong directional characters in this string, and the need to preserve a strong LTR base direction is more to do with the type of information in the string than with the content.

3.2.6 Spill-over effects

A common use for strings is to provide data that is inserted into a page or user interface at runtime. Consider a scenario where, in a LTR application environment, you are displaying book names and the number of reviews each book has received. The display should produce something ordered like this:

$title - $numReviews reviews

Then you insert a book with a title like that in the original example. You would expect to see this:

HTML: تصميم و إنشاء مواقع الويب

- 4 reviews

What you would actually see is this:

HTML: تصميم و إنشاء مواقع الويب - 4 reviews

This problem is caused by spillover effects as the Unicode bidirectional algorithm operates on the text inside and outside the inserted string without making any distinction between the two.

The solution to this problem is called bidi isolation. The title needs to be directionally isolated from the rest of the text.

3.2.7 What consumers need to do

Given the use cases in this section it will be clear that a consumer cannot simply insert a string into a target location without some additional work or preparation taking place, first to establish the appropriate base direction for the string being inserted, and secondly to apply bidi isolation around the string.

This requires the presence of markup or Unicode formatting controls around the string. If the string's base direction is opposite that into which it is being inserted, the markup or control codes need to tightly wrap the string. Strings that are inserted adjacent to each other all need to be individually wrapped in order to avoid the spillover issues we saw in the previous section.

[HTML5] provides base direction controls and isolation for any inline element when the dir attribute is used, or when the bdi element is used. When inserting strings into plain text environments, isolating Unicode formatting characters need to be used. (Unfortunately, support for the isolating characters, which the Unicode Standard recommends as the default for plain text/non-markup applications, is still not universal.)

The trick is to ensure that the direction information provided by the markup or control characters reflects the base direction of the string.