Web Accessibility: A Catalyst to Greatness, November 2012

- Video with captions

- Text transcript is below, with a few of the "slides"

The best place to start learning about accessibility is the Accessibility - W3C page, which links to details on specific topics.

Transcript

[Today we're going to] talk about web accessibility as a catalyst to greatness.

First of all, I want to start out with a little visual description for those of you who can't see. I'm female and I'm wearing a shirt with Braille across the front, across the chest. And the translation of the Braille [below it] is: If you can read this, you're too close. [laughter] Yeah, yeah. So, just a little visual description there.

What we're going to talk about is:

- how you can be great in usability/user experience,

- how you can be great in mobile design,

- how you can be great in innovation on the web.

There's a key to this and that key is accessibility. We're going to talk about how accessibility contributes to greatness in all these areas.

Accessibility is really

about

user experience,

it's about

adaptability,

it's about

flexibility, and we're going to talk about that.

[Accessibility leading the way]

But first of all, a story: Back in 1999, which seemed ages ago now, some of us started a small company and it was a usability company. We designed the website with a focus on accessibility, so it had to be highly accessible. We didn't even think about accessing this website on a phone back then. We just didn't think about it. But then the founder of the company, got one of those new fangled phones that you can look at a web page on a screen, a little screen! This was a big deal back then. So what's the first website she went to look at on her new phone? Our company's website…

It worked beautifully. This was before anyone knew anything about website design, but just the fact that we had designed it to be highly accessible and we'd followed some basic accessibility principles meant that it was adaptable and flexible enough to be used on this rudimentary mobile browser — and that's just because of accessibility.

So, a lot of what we do even today for accessibility directly relates to what we need to do for mobile design.

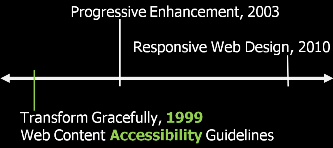

A little bit more history: How many of you have heard of 'progressive enhancement'? (Okay, most, half.) Progressive enhancement was coined around 2003. The name that pops into my head is Jeremy Keith because he talked a lot about it, but I did some research and found it was coined before then. Progressive enhancement came around as people were designing advanced web applications to take advantage of the latest technologies, and then were finding it wasn't working well on older devices, older browsers, older software, etc. So the idea behind progressive enhancement was to start at the very basic — make sure that, say, your web application can be used in older environments, and then to progressively add enhancements if the web application or the website is being used in more advanced technology. That was progressive enhancement of 2003.

Then in 2010, the idea of 'responsive web design' was coined I think by Ethan Marcotte in an A List Apart article. And responsive web design is about designing your website or web application so that it can respond to the device you're using. So whether I'm looking at a big desktop or a small little phone, it will work — that's responsive web design. I assume you've heard a lot about that.

Now, there's something that predates this by quite a bit. In 1999, a similar idea came out, way before that. Anyone have any idea what that might be?

That's the idea of 'transforming gracefully'. In 1999, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines talked about transforming gracefully, and that was again the idea that we have the content that can transform no matter how it's used. So whether it's on a small device, whether it's in a big device, whether it's older technology, whether it's newer technology, whether it's through a screen reader by a user who is blind, whether it's in large magnification — however it is [used], it will transform gracefully.

My point here is that these ideas [responsive web design and progressive enhancement] aren't new. We've been talking about those in accessibility for a long time.

[Understand Accessibility Differently]

And when you start to think about accessibility early, it can lead to a lot of these developments for what we're talking about now, for example, mobile web design. So if you want to be great, get accessibility, right?

And you may be hesitant and you should be, and I'll tell you why. It's because you really need to grok accessibility. You know that word? It means really understand it, really be one with it, really understand the concept of accessibility. So that's kind of the key to the key and I'm going to tell you a little bit about how that's different than you may think of accessibility right now.

What I want to talk about is understanding accessibility differently, totally differently than many people address accessibility.

A lot of people came to accessibility because they were forced to meet some standards or some regulations. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines came out in 1999, although a lot of people didn't pay attention to them in the U.S. Then when Section 508 came along, all of a sudden, this was a checklist, you had to pass the accessibility. And there's been other regulations around the world. People then started approaching accessibility as this thing I need to do afterwards, at the end of my project I need to pass this checklist. But that's not the right way to think about accessibility. So I'd like for you to change your mindset about accessibility, and we'll talk a little bit about that.

[Where to Start]

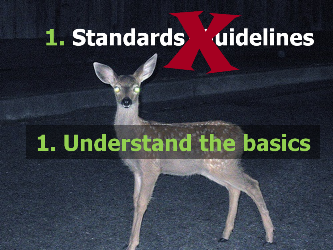

As mentioned, I do work for the W3C, the World Wide Web Consortium, and that is the organization that defines the standards for the web: HTML, CSS, etc. We have a Web Accessibility Initiative [WAI] that develops specific standards and guidelines for accessibility. So given this is my employment, you would probably assume I would say that step 1, the most important thing for accessibility, is to know those standards and guidelines… But I don't, even though that's my employment, that's not the number one thing.

If you just start out with the standards and guidelines, it's overwhelming. You'll be like a deer in the highlights, right. It's too much. That's not the place to start.

Instead, the place to start is understanding the basics of how people actually use the web. It's not about standards. It's about people, specifically, people with different disabilities and how they use web. That's the number 1 thing and the most important and the basic thing.

[People with Disabilities]

For example, I want to tell you about some friends of mine who use the web. One is Glenda. I first got to know Glenda just from mailing lists. She was on a couple of the same mailing lists that I was on. And I was just really impressed by how articulate she was, how clear, how level-headed, when the conversation got kind of uncomfortable sometimes, she was always just clear and not getting into the fray. I was really impressed with Glenda. Well, it wasn't until years later that I found out that Glenda has cerebral palsy. [mumbling] That's how she talks, so actually interacting with Glenda face to face is much more difficult. But because of accessible technology, she can contribute to this work just like anyone. She has a blog. She [calls herself] the left thumb blogger because she also has limited motor control and she just types with one thumb. She slides her hand along the keyboard. There's a video on there on YouTube if you want to check that out. So, Glenda is one of the people that we need to focus on when we're thinking differently about accessibility.

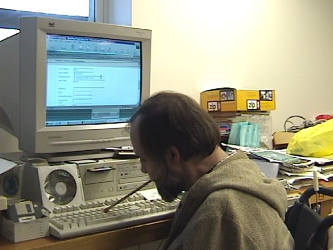

Another person who also has motor impairment is a friend of mine named Carl. Carl lost use of his arms from polio. He doesn't use his arms at all. He uses a mouthstick to type. It's just a [wooden] dowel with [an eraser] at the end. His typing looks something like this. [video of Carl typing with mouthstick] He can type pretty fast, I don't know what his words per minute are. He can also talk while he types. So we need to make sure that our applications work for people like Carl.

This is John Slatin. John started losing his sight when he was middle aged and eventually went all the way blind. John was an English professor at University of Texas. He embraced technology [the Web] as a way for anyone to communicate. John developed leukemia. And John needed to do research on treatment options. And what he found was that many of the websites that provided information on treatment for leukemia were inaccessible. He couldn't get that information. So, John is trying to make literally life or death decisions, but the information is not accessible to him. We need to make sure that all of our web applications and websites are accessible to people like John.

People who are blind use screen readers that read aloud the information on the screen. I hope most of you have heard screen readers and watched someone interact with screen readers. I won't take the time to do that now but if you haven't, that's top priority. Do it, this really will help change your thinking.

Here's another friend of mine, his name is John as well. And John was born blind and he started going deaf around age 8. All right. So he can't use a screen reader. How does he interact with a computer? Braille, exactly. He has a dynamic Braille display, they are so cool. They have these pins that pop up and provides the Braille, the output from the computer. So that's actually how John and I communicate. We just have Notepad up and I'll type on a regular keyboard and he can read it in Braille and then he'll type back in Notepad and I can read it in Notepad. Because of accessible technology, John was able to graduate top, in his class in Mathematics, and go on to get a master's degree in computer science and electrical engineering. So we need to make sure that all of our work is accessible to people like John.

Now, one of the important things is to be careful not to focus just on screen reader access and people who are blind. So, for example, I started out talking about people with motor impairments, people who have difficulty using their arms or such to interact with a computer. That was on purpose.

When we talk about visual disabilities, we also need to be aware that a small percentage of the people with visual disabilities are blind. A large percent have low vision. For example, I have optic neuritis, it's relapsing-remitting, it comes and goes. A lot of times when I look at the screen, it looks something like this which is the normal sized text. It is really too blurry to read but the larger sized text is readable. So I usually use 120, 150 percent zoom in a browser.

But some people need more significant screen magnification. Here's an example of someone with very significant screen magnification. [video] They can only see part of the screen at a time. It has some overlap with, say, mobile design where you can only see part of the screen at the time. So again, it's really important when we're talking about even visual disabilities to realize a huge variation in user needs.

This is Tim Creagan, he is at the US Access Board and he is hard of hearing. This is another thing that's very important. If you have audio on the web, whether it's a video or a podcast or whatever, and you don't have transcript or captions, that information is totally inaccessible to a person who is deaf. A person who is deaf cannot get any of that information in an audio. So if you're not providing a text description, you are discriminating against those people who can't hear. That's another very important thing to consider.

I've worked with a high school student named Sarah who is going into a college program. Looking at her you would not assume she has a disability, but she actually has a fairly significant visual processing disability. When she reads text she can't understand it. So she uses a screen reader because when she hears text, she can process information just fine. She can see just fine, but she just can't process the information that she sees as well. So she uses a screen reader. People with different cognitive disabilities are another group that we need to consider.

[Accessibility fuels innovation]

So if we think about all this, we think about people with auditory, cognitive, neurological, physical, speech, visual disabilities, you see how we can really open up our thinking. If we think not about the checklist, not about the guidelines and the requirements, but who are we really designing for, who are the people, what are the issues, what are we really designing for? This is to approach web design differently. It's a different approach to web design.

Now if you have a smartphone in your pocket, most of the technology developed for that smartphone came from innovations for people with disabilities. Even the very basis of a phone comes from developments to accommodate and to help people with different disabilities. Elle Waters will do a presentation later where she's going to talk some more about this so I won't go into the many, many examples of how something that was developed for a person or people with disabilities is now in the mainstream technology that you have in your pocket.

The idea is that thinking differently leads to innovation. When you're thinking about all different people in different situations, it really leads you to think differently and innovate in new and unique ways.

[Accessibility through usability practices]

So how do you do that? How do you think differently? How do you consider all these people? Any ideas? You meet with them? Exactly, you meet with them. You can do very informal meetings, you can do more formal processes. For example, user-centered design or user experience or usability has very specific processes and techniques that you can use to understand how people use the web.

ISO has a definition of usability. Anyone know that? Yeah, yeah, okay. It's:

The extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals effectively, efficiently and with satisfaction in a specified context of use.

That's the definition of usability in ISO. Now, this is achieved through a user-centered design process. How many people know basics of user-centered design process? About half. Here's a summary:

a user interface design process that focuses on usability goals, user characteristics, environment, tasks, and workflow…

follows a series of well-defined methods and techniques for analysis, design, and evaluation

an iterative process, with steps are built in from the first stage of projects, through implementation

[Just Ask: Integrating Accessibility Throughout Design]

The idea is that you can follow user-centered design to understand accessibility, understand how people use the web.

Now when we look at the ISO definition of usability, if we pick out a few words, so it says, "use by specific users." And all you have to do is make sure your definition of those specific users includes people with disabilities, people with a wide range of abilities. And then it says, "in a specified context of use." [Accessibility is] making sure that the context of use is broad, that it includes, for example, assistive technologies like screen readers and screen magnification, etc. If you know any usability specialists or user-experienced professionals, this should be right up their alley.

Now, some people are onboard and some people have yet to see the light. If you're a developer and you want to go beyond the checklists, following usability principles, methods, and techniques will help you with that.

If you want to learn more about this, the W3C WAI has some information called "Involving Users in Web Projects for Better, Easier Accessibility" This is mostly geared towards developers and designers, not particularly usability specialist. You said, "Observe people" — this talks about finding people and observing them, talking to them. So, that's some basic information.

Now, if you know someone who is a usability specialist or really wants to get involved with this, I've written a book called "Just Ask: Integrating Accessibility Throughout Design." The whole thing is online free. So, it's available from uiAccess.com/JustAsk. It's primarily geared towards usability professionals, but the beginning is the basics that you can implement even if you're not doing full user-centered design process. If you're interested in getting a print copy, for those who are here, we have a discount in November. So from that website, you just enter a11yMTL.html and you can get a discounted version if you want to print a copy. But the whole thing is online for free as it is. So, that's another resource.

[Resources]

We're going to look at a few other resources that we have from the W3C WAI on designing for inclusion. We have an extensive document on How People with Disabilities Use the Web. It has several different sections. One talks about the user stories to help bring those to life. There is a section on the technology that people use. There's a section on what are the accessibility requirements of websites and web tools. So, I encourage you to take a look at How People with Disabilities Use the Web.

We have another resource called Web Accessibility and Older People: Meeting the Needs of Ageing Web Users. We had a 3-year, European Commission-funded project to look at designing for older users. And what we found at the end of that 3-year project was that, indeed, [there is nearly] a one-on-one overlap with designing for accessibility. So, we already know how to design for accessibility. And what we found is it's the same issues if you're designing for older users, because older users have a range of issues.

Let's do a little exercise for that and give you a chance to stretch your feet. I'd like everyone to stand up. [ Pause ] Okay, what I'd like is for you to pick one of the gray figures on the screen. On the screen we have a representation of the percentage of people with disabilities. This is in the age group 18-24 years, okay? And it's 9.5 percent. So, pick one of the gray figures. We're going to go through aging. And if your figure turns color, have a seat, okay? This is 25 to 34 years, 10 percent and we lost 2, 3 people there. This is 34 to 44, 14.4 percent. 45 to 54, 21.2 percent. 55 to 64, at 34 percent. More people dropping. 65 to 74, it's 42.3 percent. 75 and over, 64 percent. Now, look around the room. We have less than 64 percent. We have four people standing. (Those of you who are standing, unfortunately, this isn't the true predictor of real life, so I can't guarantee that you're going to make it without a disability. [laughter]) Thanks, you can have a seat.

The point is most of us will live to 75 and most of us will acquire significant disability. Minor disability at first may be from declining eyesight, from declining dexterity, from declining hearing, cognitive disabilities — all these are significant. This can start out small. It can get really annoying. And can be much more of an impact on how people use your web products.

Designing for older users is becoming more and more important, and more and more of a focus of both government and industry and non-profits [NGOs] and everyone. This is focused on meeting the needs of older users. In order to do that, you can look at what we already know about accessibility. We have resource on that.

We have other resources on [Mobile Accessibility and] Web Content Accessibility and Mobile Web. I've mentioned just briefly the overlaps, but we have a specific document on that overlap. Now, this talks about how the standards and best practices overlap between the two.

[Accessibility standards]

I just said that word 'standards'. Even though at the beginning, I said that the standards are not the first place to go, they do play an important role. I still say that the first step is to understand the basics. But maybe around step 3 is to start looking at the standards and guidelines, and then probably again maybe at step 7 or somewhere around there.

They do have an important role. One reason is that there's no way you can fully incorporate enough people and enough variety in your design process. Even if you have a huge budget and a huge amount of time, there's so much variety in people, in how we use the web, and how people with disabilities use the web, that you won't be able to cover it all. The standards/guidelines do that for you, they consider this wide-range.

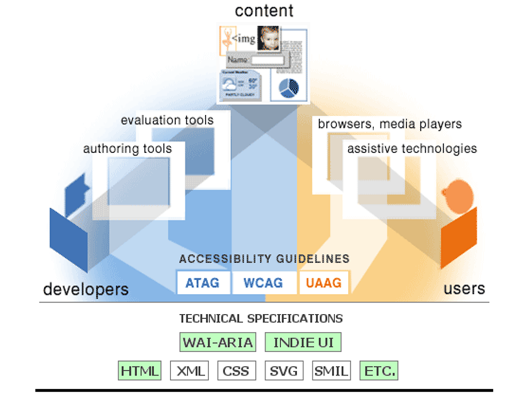

I'm not going to go into detail on these [W3C WAI accessibility standards], I'm just going to make sure you know what's there, and if there are any questions, we can follow up afterwards. Again, the W3C defines the standards for the web. The standards we have for accessibility are an integrated set.

- [WCAG] You may have heard of WCAG or the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines — that applies to websites, that applies to web applications, that applies to mobile applications.

- [UAAG] Then, another aspect of [accessibility] is that users use browsers and other technologies to access the web. And we have guidelines for those called the User Agent Accessibility Guidelines.

- [ATAG] Another one is the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines, and that talks about what the tools that we use to design web content need to do to support accessibility.

[These are explained in Essential Components of Web Accessibility and the "Components of Web Accessibility" Presentation and Step-by-Step Guide.]

These are built on the technical specifications from the W3C. We also have some specifically for accessibility, such as the WAI-ARIA for Accessible Rich Internet Applications, and Indie UI which is Independent User Interface. That talks about how to communicate a user action to an application no matter how the user did it, so whether they scrolled with a gesture, whether they used a mouse, whether they used voice input, however. Okay, [that was] just a brief introduction.

Also a note that WCAG 2 is now an ISO standard. So if you're working on WCAG 2, now you can say you're also working on an ISO standard. It's exactly the same, the same text, it's just adopted now as ISO/IEC 4500.

Again, if you have any questions, I'll be around at the break and afterwards.

[Approach Accessibility Differently = Catalyst to Greatness]

[Finally,] I just want to reiterate that

Accessibility is about designing your website so that more people can use it effectively in more situations.

It's much more broad than just [benefiting] people with disabilities. [People with disabilities] are the most important aspect that we focus on, but the benefits are far reaching. So if you understand accessibility differently, it's not about a checklist to do at the end, but it's a fundamentally different way of thinking about your web design and your web development. — If you understand accessibility differently, you will approach web design differently. An interesting article from A List Apart several years ago by John Allsopp is called the "Dao of Web Design." He says, "Firstly, think about what your pages do, not what they look like. Make pages that are adaptable. The journey begins with letting go of control and becoming flexible."

When you change your way of thinking, you'll understand accessibility differently, you approach web design differently — and this is a catalyst to greatness: greatness in usability and user experience for a wide range of users — whether it's on the mobile platform, whether it's because they are older, it's all these things that you want to do better at, you can learn from understanding accessibility.

So I encourage you to approach accessibility as a catalyst to greatness.

And I thank you for your time.