WAI R&D Symposia » Way-Finding Home » Proceedings » This paper.

This paper is a contribution to the Accessible Way-Finding Using Web Technologies. It was not developed by the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) and does not necessarily represent the consensus view of W3C staff, participants, or members.

Extended Abstract for the RDWG Symposium on Accessible Way-Finding Using Web Technologies

Human Access: evolution of a crowdsourcing accessibility evaluations mobile app

- Christos Kouroupetroglou, Caretta-Net Technologies, Greece, chris.kourou@cnt.gr

- Adamatios Koumpis, University of Passau, Germany, adamantios.koumpis@uni-passau.de

1. Problem addressed

Persons with Disabilities (PwD) are often facing challenges in their everyday life when they need to access buildings, venues and generally places with no appropriate infrastructure or accommodations for them. Human Access [4] is a mobile application with an accompanying web app currently in development, allowing users to rate specific accessibility related features of venues and places around them in order to explore places easier in the future. The application has been published on Google Play [3] for almost one year now and this paper describes the rationale behind some choices that were done in the data gathering methodology, looking in parallel approaches followed by already existing applications.

2. Relevant background

In this section we are going to present various applications and their approaches in gathering such information and how their approaches formed lead to the one followed in Human Access.

The first approach to be presented is the one followed by Wheelmap [7] which is an application that enables to rate the accessibility of various places and consequently search and get information about the accessibility of rated places. A strong point of Wheelmap is the technical infrastructure that lies underneath and is based on OpenStreetMap [6] where users of various applications are providing information to create their own maps. However, the accessibility rating is based on a single attribute giving information about wheelchair accessibility and not being able to get or store information for different kinds of needs such as existence of Braille in the elevator, or loud music/noise etc. Moreover, the infrastructure of OpenStreetMap does not allow for storing multiple evaluations from different users. The information is stored using a model similar to a wiki, so whatever evaluation is inserted or updated by a user stays as it is until another user updates it.

Jaccede [5] on the other hand enables the rating of a variety of attributes but keeps its own database of geographical information making it more difficult to cooperate with other applications. The properties rated by Jaccede members are often tied with actual measurable physical properties such as the width of an entrance. An interesting approach followed by the specific company is that they often organize community events in order to train and massively collect information in specific cities. The participants in such events are given a set of tools like evaluation sheets and a measure and within a specific given area they are rating businesses during a day.

Another example for such detailed information gathering can be seen in AbleRoad [1]. AbleRoad is using a 5 stars rating schema for a variety of properties. However, an interesting feature is that properties are separated in 4 groups based on disabilities. Τhere are properties for mobility, hearing, sight and cognitive disabilities. Each category includes about 12 properties. This makes a total of about 48 properties. This kind of analysis means that the data kept by AbleRoad can describe quite detailed the accessibility in a place similarly to Jaccede. However, a question that rises in such an extensive evaluation schema is how easy it is for a user to do a complete evaluation. Users of such applications especially on mobile phones won’t probably be that keen to evaluate tens of properties.

Contrary to extensive evaluation schemas or simple unique attributes there are also a number of applications that utilize a more minimal set of attributes for a place. Such an example is AXSMap [2]. AXSMap, uses a set of 3 basic 5-star attributes combined with 6 true/false attributes that allow user to evaluate critical aspects of accessibility in a place. This way rating the accessibility of a place becomes easier than having to fill out a long form of attributes. An interesting approach and concept introduced lately by the app is the gamification through the idea of a mapathon. In particular, the application allows users to organize events challenging their friends to evaluate places in a specific timeframe. This way, the application tries to engage more users and help communities organize and collaborate to solve their local problems.

The approach of Human Access

Human Access was developed well after the aforementioned applications. Moreover, it started as a mobile application rather than a web site or web app. Starting as a mobile application our intent was to make it as easy to use as possible so the process for evaluating a place was kept to a simple 2 steps process. The user selects a place from the nearby places list, which is taken from Foursquare and then rates 6 attributes related with its accessibility. Namely, the attributes included in the first versions of Human Access are:

- Lighting level

- Noise level

- Entrance accessibility

- Internal space accessibility

- Toilets for PwD

- Parking area for PwD

Having seen different approaches in rating accessibility of places Human Access decided to follow an approach similar to AXSMap and Rollout for the sake of eliciting more evaluations. Since the application is a mobile one, we expected people to evaluate places while they are on the spot. Therefore, we needed a process which will not distract them for a long from their regular activities and social context. That is why we selected only 6 attributes and a simple 5 star rating scheme which feels very natural to users for evaluation purposes.

This simplification of the process however does not come at the expense of some potential benefits from a more elaborate and exhaustive evaluation. One such danger is that people searching for a place might not get all the information they need. That is why the attributes selected were as generic as possible and apply to most of the venue types (e.g hotels, restaurants, cinemas, etc.). Another danger is the misunderstanding of attributes that could lead to wrong evaluations. That is why we included a feature of more elaborate descriptions of an attribute that appear if a user touches the name of an attribute.

Finally, Human Access is storing all evaluations form users together with a timestamp and shows an average of the rating for each attribute. The timestamps will also allow Human Access in the future to assign different weights to more recent than older evaluations and this way reflect changes in infrastructure of a place.

4. Outcomes

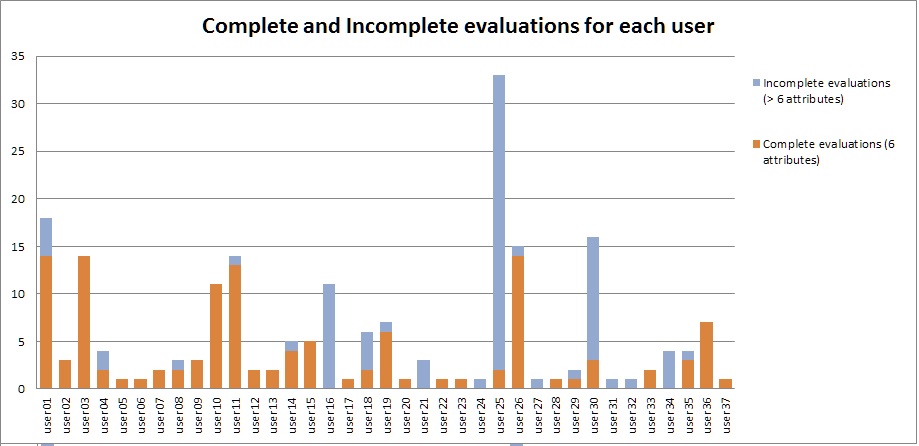

After about one year of usage Human Access has now 201 venues that have been evaluated. Looking at the users’ behavior in terms of users submitting complete or incomplete evaluations, we can also see how users behaved towards the 6 attributes list. Figure 1 shows the number of complete and incomplete evaluations that each of the 37 active users has done. 25 (67,5%) of the users used more complete than incomplete evaluations and 18 out of these (48,6%) had all their evaluations using all six attributes. This means that almost half users used the applications for submitting complete evaluations. This information does not explain the cause for that behavior but needs more research to identify the reasons behind that.

Figure 1: Complete and Incomplete evaluations per user

5. Conclusions

Forming a strategy to gather information about accessibility of places depends on a variety of factors. Some applications select to go with detail and depth in their evaluation risking this way the possible breadth that a simpler evaluation schema might provide. Other applications follow the opposite direction of small sets of attributes to be evaluated so that evaluations are easier to be done but not in detail. Human Access as a new application in the domain decided to use the strategy of small set of attributes mainly because of its mobile character. Users completing evaluations in the first stages of the applications seemed to respond well in that choice by selecting to submit complete evaluations using all 6 attributes. Although such a decision might prove to be problematic in the future where more detailed information might be requested by users Human Access follows an architecture which enables the extension of rating criteria and the grouping of new attributes under the already included generic ones.

References

- AbleRoadTM - Disability Access. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://ableroad.com

- AXS Map. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.axsmap.com/

- Human Access - Android Apps on Google Play. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2014, from https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.kourou.fouraccessq

- Human Access: Home. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://ha.cnt.gr/index.php

- Jaccede.com - le guide collaboratif de vos bonnes adresses accessibles ! (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.jaccede.com/fr/

- OpenStreetMap. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=5/51.500/-0.100

- Wheelmap.org - Rollstuhlgerechte Orte suchen und finden. (n.d.). Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://wheelmap.org/