Object Memory Model

W3C Incubator Group Report DRAFT

- This version:

- http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/w3omm/XGR-w3omm-20110926/

- Latest version:

- http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/w3omm/XGR-w3omm/

- Authors:

- Alexander Kröner, DFKI (Chair, Editor)

- Jens Haupert, DFKI

- Marc Seißler, DFKI

- Bruno Kiesel, Siemens

- Barbara Schennerlein, SAP

- Sven Horn, SAP

- Daniel Schreiber, Technical University Darmstadt

- Ralph Barthel, UCL

- (other authors)

Copyright © 2011 W3C® (MIT, ERCIM, Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C liability, trademark and document use rules apply.

Abstract

The Object Memory Modeling Incubator Group defined an object memory model, which

is meant to provide a container for information concerning some a physical artifact, and wants to support collecting data related to this artifact as well as making this data accessible via web-based structures. On the basis of such a unified model, the resulting object memory then may be employed in order to address use cases such as provenance of artifacts, automation, supply-chain management as well as human interaction with artifacts in terms of a ubiquitous web.

This report describes the role and scope of the object memory model, provides an examplary mapping of the model to an XML-based object memory format, and illustrates the application of this format on the basis of selected use cases.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Status of This Document

This section describes the status of this document at the time of its publication. Other documents may supersede this document. A list of Final Incubator Group Reports is available. See also the W3C technical reports index at http://www.w3.org/TR/.

The object memory model presented in this report is discussed on the basis of an XML-based object memory format. This should not be considered to be a limitation, as experiments initiated by members of the incubator group have shown that this model can easily be translated to various other encodings. Furthermore, the object memory model does not implement the object memory as a whole. Complementary structures are suggested in order to facilitate the interaction with an object memory, such as an API. These aspects are out of scope for this particular report, but are investigated by members of the incubator group. For information concerning this reference implementation, please see LINK.

This document was developed by the Object Memory Modeling Incubator Group.

Publication of this document by W3C as part of the W3C Incubator Activity indicates no endorsement of its content by W3C, nor that W3C has, is, or will be allocating any resources to the issues addressed by it. Participation in Incubator Groups and publication of Incubator Group Reports at the W3C site are benefits of W3C Membership.

Incubator Groups have as a goal to produce work that can be implemented on a Royalty Free basis, as defined in the W3C Patent Policy. Participants in this Incubator Group have made no statements about whether they will offer licenses according to the licensing requirements of the W3C Patent Policy for portions of this Incubator Group Report that are subsequently incorporated in a W3C Recommendation.

Remarks to the authors

- The original concept of a memory format might no longer be appropriate. Instead, we might go for a generic model, which can be encoded in various ways - such as the XML-based Object Memory Format.

The mission of the Object Memory Modeling Incubator Group, part of the Incubator Activity, is as follows: To define an object memory format, which allows for modeling of events or other information about individual physical artifacts - ideally over their lifetime - and which is explicitly designed to support data storage of those logs on so-called "smart labels" attached to the physical artifact. Such labels range from barcodes, to RFID, to sensor nodes - miniaturized embedded systems capable of performing some processing, gathering sensory information and communicating with other nodes. The object memory format implemented on a "smart label" can provide an object memory, which may serve as a data collector for real world data concerning a physical artifact. Associating semantic definitions with the data stored using the object memory format, can help tie together the Semantic Web with the Internet of Things.

Today, heterogeneous standards are already in use to describe a physical artifact's individual characteristics in different application domains. The envisioned object memory format has to complement and embrace such standards dedicated to the description of physical items. In order to facilitate interoperability in scenarios comprising several application domains (e.g., business processes covering production and logistics) and open-loop scenarios (e.g., production lines with highly varying process steps), the object memory format should provide a standardized way to organize and access the selected data independent from the application domain. Furthermore, it should function as a technology-neutral layer for delivering content from physical artifacts to applications in business processes ranging from product lifecycle management to consumer support.

This report summarizes common agreements and results achieved by the members of the Object Memory Modeling Incubator Group. Its structure resembles to some extent the process that was employed in order to investigate this topic.

This document investigates and motivates structural characteristics of a data model for object memories - the OMM. It is meant for readers interested in several areas.

- Automation and supply-chain management

- An object memory wants to strentghen the role of an artifact in such processes, making it a tool for collecting and communicating data - and thus for documenting and steering processes.

- Smart Items

- Object memories can be used to let (digital services linked to) artifacts act smarter, as they can be exploited for storing previous applications of an artifact.

- Ubiquitous Web and Internet of Things

- The structure of the OMM was developed with a Web-based application in mind, and thus might contribute to the linking of physical artifacts with Web-based structures - in particular, by making data records about artifacts available in a unified way that easies their inclusion in Web pages.

- Provenance

- Object memories are explictly meant to support humans as well as machines in exploring the provenance of an artifact - e.g., where and under which conditions a certain product has been produced. Consequently, the OMM could be interpreted as a model of artifact provenance (see LINK Provenance).

The Object Memory Model was developed in the W3C context for several reasons. These share the idea that it should optionally be possible to store object memories in the Web in order to facilitate building and communicating such data:

- Long-term storage

- On a conceptual level, object memories want to support collecting data concerning individual physical artifacts - up to a complete lifecycle data collection. Use cases in general suggest a tight linking of artifact and memory - up to a physical connection of artifact and memory device. However, despite that linking, some use cases impose constraints, which suggest that the memory should be accessible without having the artifact at hand - e.g., if the artifact got lost or has been consumed.

- Community-generated content and open access

- Object memories are also meant to support communication concerning individual physical artifacts. Use cases include scenarios, where users not in possession of the articaft discuss the artifact.

- Shared resources

- While the object memory concept explitly wants to support a data model for the individual artifact, several artifacts (and thus object memories) may nevertheless be required to share some data resource for reasons of efficiency. For instance, a single multimedia manual can be shared by all object memories of objects of a certain product series.

- Memories for the Internet of Things

- An object memory should become part of an Internet of Things: artifacts may be assembled from several parts, each of them equipped with an object memory. This implies a linking mechanism for the data model employed for organizing object memories.

Consequently, the OMM XG suggests with the OMM a structure which can be integrated with Web-oriented infrastructures.

The idea of an Object Memory Format was the outcome of intense discussions between members from industry and research active in several research projects. While all of these projects had differing research goals, there was a shared interest in linking physical artifacts with a continuously growing store of digital information.

- The SemProM project

- The SemProM project (Semantic Product Memory, see http://www.semprom.org/) researched how smart labels may give products a memory and thus support intelligent applications along the product's lifecycle. By the use of integrated sensors, relations in the production process become transparent and supply chains as well as environmental influences retraceable. The producer gets supported and the consumer better informed about the product.

- The ADiWa project

- The ADiWa project (Alliance Digital Product Flow, see

http://www.adiwa.net/) makes the huge potential of information from the

Internet of Things accessible for business-relevant workflows that can be

strategically planned and manipulated. For the data-level connection of

objects from the real world, results from available solutions and from

the SemProM project shall be used. ADiWa focuses on business processes,

which can be controlled and manipulated based on evaluated information

from the real world.

- The Aletheia project

- The Aletheia project (see http://www.aletheia-projekt.de/) is a leading

innovation project, sponsored by the German Ministry of Education and

Research that aims at obtaining comprehensive access to product

information through the use of semantic technologies. The project follows

an approach which does not only consult structured data from

company-owned information sources, such as product databases, to respond

to inquiries, it also looks at unstructured data from office documents

and web 2.0 sources, such as wikis, blogs, and web forums, as well as

sensor and RFID data.

- The SmartProducts project

- The SmartProducts project (see http://www.smartproducts-project.eu/)

develops the scientific and technological basis for building "smart

products" with embedded proactive knowledge. Smart products help

customers, designers and workers to deal with the ever increasing

complexity and variety of modern products. Such smart products leverage

proactive knowledge to communicate and co-operate with humans, other

products and the environment. The project thereby also focuses on small

devices with limited storage capabilities and thus also requires

efficient storage mechanisms. Moreover, the project aims to apply the

results achieved by the incubator group for optimizing the data exchange

between different smart products.

- Tales of Things

- Todo

These projects provided input to the incubator group from practical experiments with preliminary results generated by the group. Furthermore, they supported the incubator group with complementary activities such as market research concerning business models that could drive the transfer of a potential standard into practice.

General requirements for the object memory format include:

- Independence from the application domain;

- Independence from technical constraints imposed by smart label technology;

- Openness, flexibility, modularity and scalability

An object memory format addresses the organization, the description and the transformation of object-related information. Hence, the use of the following three components is playing a prominent role:

- A structure model defines the structural characteristics of an object memory. It should provide a flexible and extensible approach, such that any potential owner of the object will be able to enrich the representation with additional information in arbitrary formats. This model should explicitly support the temporal and incremental aspects of information accumulation along the object's lifecycle and allow for describing the state of the object at different points in time. In addition, it should allow for describing active components, such as sensors, employed by the object to acquire information from its environment. Furthermore, this model should be designed in a way which facilitates its adoption on technically limited information storage devices such as RFID chips. Further, it should enable an efficient information exchange between objects.

- A set of well-defined metadata enables a superficial characterization of a physical object without need to access additional information sources. This metadata (keywords) should be used by any kind of object memory in order to facilitate information exchange in scenarios with several parties interacting with the object.

- A conversion format should provide a defined but flexible way to transfer the object memory format to a representation matching the technical constraints of various types of labels ranging from barcodes to sensor nodes. It should allow for defining mappings between an XML-based representation of the object memory format and arbitrary binary formats with potentially strong technical

limitations.

The object memory format will further provide mechanisms to support: data access; interpretation of data; and data integrity for distributed information linked with an object.

In order to explore this topic, the following sequence of work was employed:

- Analysis of requirements for data storage and processing on the physical

item and externally in the environment. Notes: This includes processing object

memories on the physical item's smart label.

- Definition of a structural description for object memories, which allows

for defining content blocks and histories of events for an individual

object. Notes: There are no agreed

formal definitions for the structure of object memories at present.

Creating agreed formal definitions will be a task of the incubator group.

Furthermore, constraints imposed by physical aspects of smart label

technology should be taken into account in order to enable a transfer of

these structures from Web-based scenarios to smart labels.

- Definition of structures that facilitate access to and description of

content stored in object memories, such as keywords and index structures.

Here, a particular objective is to define these structures in a way that

permits quick direct access to data even after a transfer (and potential

conversion) of such structures to arbitrary smart labels. Notes: An

important requirement is to record product decomposition in an "open

world", i.e., these structures should be ready for extensions. Notes: An important requirement is to

record product decomposition in an "open world", i.e., these structures

should be ready for extensions.

- Definition of a description, which allows for the specification of

associated remote data sources such as object-related sensors - sources

which may feed the object memory with content. Notes: Following the related concept of

smart labels, a particular focus will be on the description and treatment

of information sources actually attached to the physical artifact.

- Definition of structures supporting the conversion from XML-based

representations to other, more compact (e.g. binary) formats appropriate

for different kinds of smart label technology. Notes: This particular step will require

a formal description of the mapping process; the approach should be open

and thus allow content providers to define their own mapping schemes for

their respective contents.

Matching the initial expectations issued in the charter, the incubator group's efforts focused on items (1), (2) and (3) during its one year runtime. The group started to investigate items (4) and (5); a corresponding proposal of how to deal with these topics - also as part of future work - is included in this document. During the runtime, the group aligned its activities according to the success criteria of defining a (re)usable structure, which

- Describes a physical artifact's individual characteristics and

technical capabilities.

- Enables the representation and organization of individual event histories

(and thus the evolution of properties of a single artifact).

- Supports retrieval and access of changing owners and users along the

product lifecycle.

- Is ready for translation according to (memory) constraints imposed by

smart label technology.

The object memory model has a strong focus on introducing new structures only if needed for the particular purpose of an object memory. Consequently, the following activities are considered related, but out of scope for the purpose of this group. Their respective results were embraced where possible in order to ease the deployment of new elements created as part of the object memory model.

- Modeling of product or object properties

- The OMM provides a structure for organizing and accumulating information about physical artifacts, which may, but must not be products. Project models are considered to be contents of an OMM. Consequently, efforts such as Semantic Product Modeling, which aim at semantically rich product descriptions, are considered complementary to the OMM.

- Product classification models

- There exist various standards for classifying products, such as eCl@ss. Often tailored for a particular application domain, these standards have there own justification - and it might even be necessary to provide several descriptions, e.g., in order to reflect changing information interests along a product's lifecycle. Furthermore, these structures are meant for classifiying, and thus do neither reflect the characteristics of an individual object, nor change in an object's properties. The OMM does not want to establish a new means of classifying products. Its structure explicitly allows for storing several classifications, and is tailored for continuous extensions of the referred data collection.

- Object identifiers for the Internet of Things

- Applications in the Internet of Things usually require the identification of physical artifacts by means of a standardized identifier associated with the respective object. For the identification of objects several standards exist. Some of them are widely used, for instance EPC, EAN or GTIN codes - stored as barcode or RFID data tag, or the use of DUNS numbers for companies and manufacturer identification. In the scope of Internet of Things new identification standards came up, not only for products, also for more unspecified "things". Most important here is the IPV6 standard, which allows 6.5 x 10^23 addresses for each square meter worldwide. Other identifications like the ID@URI or DOI - the Digital Object Identifier are also common. Some of the identification systems require a registration; some are also not free of charge. Mostly the scope of the product use or handling defines which identification system should be used. The OMM does not want to introduce a new identification standard, and explicitly seeks to support information collection across several of such scopes. Therefore, the OMM allows for storing several identifiers. One of them may optionally be marked as primary identifier in order to support efficient identification of the object.

- Modeling complex events

- Complex event processing is a technology used for providing real-time insights of events in business networks. Applications aim, for instance, at a greater end-to-end process visibility and therefore a higher agility of business processes. Based on a huge data stream of single data (e.g. recorded and send by sensors) this data are analyzed and complex events are defined. A complex event is a specific combination of simple events that represents a condition, a trend, or a change that is meaningful to an organization. While the OMM's block-based nature is meant to support a sequential organization of data (including event models), modeling complex events would be out of scope of this structure.

- Recording process instances

- Use cases of the OMM frequently describe scenarios, where an object is subject of a well-defined process (e.g., manufacturing). For modeling such a process, different standards exist. For instance, is the related area of business process modeling, prominent modeling approaches are BPMN 2.0 and event-driven process chains. These are used for the conceptualization of business processes and for the description of automatically executable workflows. While an object memory may accompany an object through such a process, the OMM itself does not want to model such a process. It may serve as a container for such a process, and its structure supports the creation of such records to some extent (e.g., with clearly seperated blocks for step-wise recording and metadata for indexing records).

- Access logging

- For use cases such as Process Documentation (see Section 4.1) it might be interesting to record access to an object memory explicitly indenpendly from the OMM's block-based structure. The XG members decided against supporting access logging more explicitly due to the strong dependency of an access log's reliability from the employed (software-) mechanisms for enforcing access logging.

- Secure access and content integrity

- Secure Access to digital object memories consists of two parts. First the secured data transfer, to avoid external observers to clearly see the interaction (read, modify and write actions) done with the object memory. Second the data integrity during data transfer to ensure that nobody (as man-in-the-middle) is able to modify the data during transport. The realization with certificates (e.g. X.509) is widely used to ensure data integrity and enable secure entity authentication. But these features are not part of the OMM because the model only deals with the general memory structure and techniques to easily find and access the wanted data, and does not cover the topics how to store and how to access such memories.

The Physical Markup Language (PML) provides an XML-based mechanism for modeling physical properties of an artifact including aspects related to supply-chain management such as changing ownership or responsibilities. While the OMM XG members consider the firmer aspect to be out of scope of an OMM (see Section 1.3), the OMM is sharing some ideas of the latter aspect. While the OMM can be applied in the context of business processes (see, e.g., Section 4.1), it explicitly focuses only on the memory structure in order to emphasizes openess of the model and to guarantee independence from the application domain.

Relationship of event logging to OMM

Common Event Expression (CEE) is an active standardisation project with a focus on how computer events are described, logged, and exchanged. Information about the project can be found at the CEE website. The documentation contains an overview over the technical architecture and drafts of the CEE language specifications.

Unlike other event logging standards that are mainly concerned with web server logs such as W3C Common Log file format and W3C Extended Log File format CEE aims to improve overall audit processes and to increase interoperability between event and log formats.

CEE contains of a number of different elements and will offer different levels of conformance. The specification contains of a log syntax (CLS) that describes how an event and its data are represented. The collection of possible event fields and value types of event records are described via a CEE Dictionary and the CEE Taxonomy defines a collection of tags that can be used to categorise events. The CEE community provides log recommendations (CELR) that are aimed at providing best practises what data to log and how to log it. Finally another part of the specification (CLT) describes what technical support is necessary (e.g. internationalisation, interfaces for event recording) to support the transport of logs.

After several years of discussion the standard IEEE 1451.7 (identical to ANSI 1451.7) has been published on the 26th of June 2010. Its full title is "Standard for a smart transducer interface for sensors and actuators-transducers to radio frequiency identification (RFID) systems communication protocols and transducer electronic data formats".

This standard includes a binary data model for describing the key features of the sensor / actuator as well as different event logging mechanisms. Different types of events and summaries (e.g., max value, means) are given. Finally an interface (also binary) to the transducer is given.

Because of its focus on binary representations and its narrow field of application, the approach is probably not directly applicable to our approach. Nevertheless, its extensive listing of event types and logging mechanisms is interesting.

An object memory seeks to enable different parties to contribute data to the memory (e.g., in order to record the exchange of an artifact between business partners), but also to provide a clear distinction of all of these contributions. As such, provenance of an object memory is two-fold: First of all, provenance of contributed data has to be represented. Second of all and depending on the use cases, the overall memory may represent the provenance of an artifact. Here, provenance of contained data is not constrained to a particular subject. The OMM relies on metadata in order to support retrieval of contained data. The reference implementation uses metadata based on Dublin Core Metadata (see Section 2.6) in order to describe provenance of contents within the memory.

Therefore, the OMM is related to some extent to activities devoted to provenance modeling - such as the W3C Provenance Working Group., which is aiming at a widespread publication and use of provenance information of Web documents, data, and resources. The OMM on the one hand side may contribute to this activity. In turn, a generic provenance model (or mapping) would be of particular use for OMM-based applications: it is likely that scenarios involving parties from different application domains would result in object memories with contents following differing provenance models.

to be done, link

"The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative, or "DCMI", is an open organization engaged in the development of interoperable metadata standards that support a broad range of purposes and business models. DCMI's activities include work on architecture and modeling, discussions and collaborative work in DCMI Communities and DCMI Task Groups, annual conferences and workshops, standards liaison, and educational efforts to promote widespread acceptance of metadata standards and practices" (see http://dublincore.org/).

Together with the W3C's generic data model for metadata, the Resource Descriptive Framework (RDF), the Dublin Core Community developed application profiles

leading to the creation of a core set of metadata extended with special domain specific data, that enabled us to use some of the Dublic Core metadata

for our purposes and extend them with additional information, rather than defining a complete new set. So we used the core attributes

Title, Description, Format, Creator, Contributor, Subject (partially) as foundation for our metadata set. We extended these core types with additional features to

support our needs and complemented them with auxiliary object memory specific information.

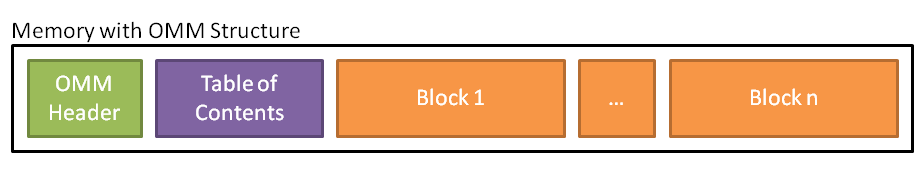

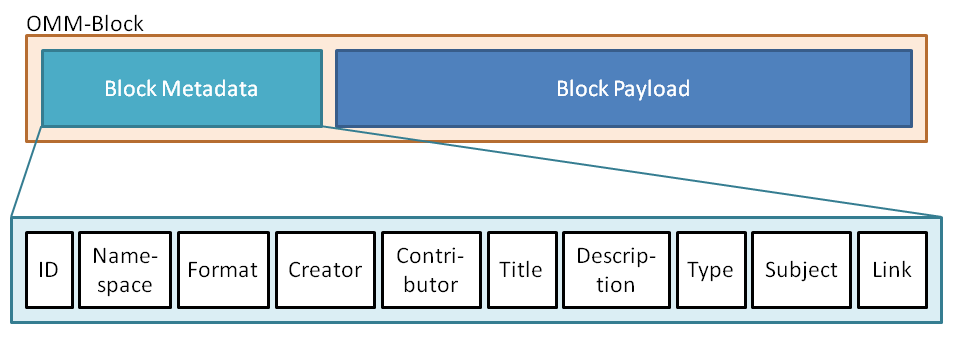

Figure 1: General OMM Structure

The proposed object memory model (OMM) partitions the object's memory in several blocks.

Each block contains a specific information fragment and consists of a set of meta data

to ease search tasks the data itself (see Figure 1).

This list of blocks is supplemented with an optional table of contents (ToC, see chapter 3.2)

and a OMM header section. This header contains the version of the OMM, a primary unique ID for

this object memory and the link to additional block sources.

The following examples shows an OMM

header with Version 1 (<omm:version>, mandatory),

the URL "http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/samples/p1" as primary ID (<omm:primaryID>, mandatory) and

the URL "http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/samples/p1/ext" as source of other OMM blocks (<omm:additionalBlocks>, optional),

that can be fetched via http (==> type "omm_http").

<omm:header>

<omm:version>1</omm:version>

<omm:primaryID omm:type="url">http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/samples/p1</omm:primaryID>

<omm:additionalBlocks omm:type="omm_http">http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/samples/p1/ext</omm:additionalBlocks>

</omm:header>

Something missing?

CHECK: "primaryID" vs. "ID-Block"?

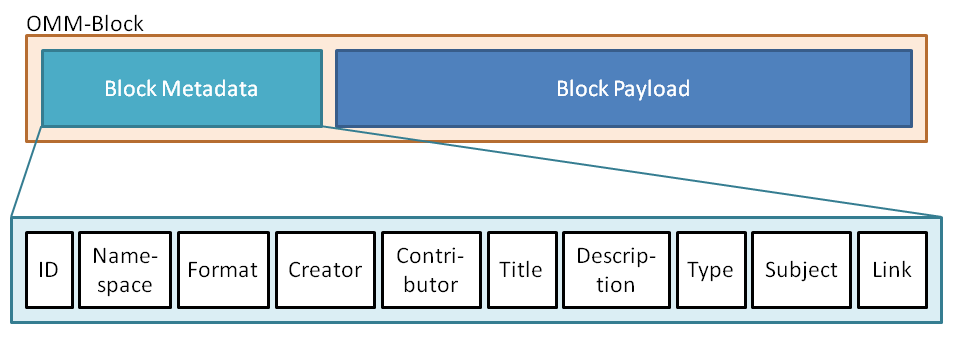

Figure 2: OMM Block Metadata

Each object memory block contains information about a specific topic. This topic is indicated by a set of meta data attributes,

to enable other users to find the correct blocks (see Figure 2). The following overview shows the meta data attributes in detail:

- ID

- Namespace

- Format

- Creator

- Contributor

- Title

- Description

- Type

- Subject

- Link

Payload

- Purpose: Allows inline payload storage as alternative to the linked structure.

- Type: CDATA (plain text or xml strucutures).

- Attributes:

- Encoding (<omm:encoding>, optional): Indicates the binary encoding used for this payload (e.g. "base64")

- Optional (Mandatory, if no "Link" is given)

- Necessity: Inline payload, without the necessity of any external storage.

- Code sample: TODO

The following box shows a complete sample for an OMM block with several meta data, link and payload information (just for this example though link and payload never appear in the same block):

<omm:block omm:id="block_123">

<omm:namespace>http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ns/sample</omm:namespace>

<omm:format omm:schema="http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/schema/sample.xsd" omm:encryption="none">application/xml</omm:format>

<omm:creation>

<omm:creator omm:type="duns">195505177</omm:creator>

<omm:date omm:encoding="ISO8601">2011-01-30T18:30:00+02:00</omm:date>

</omm:creation>

<omm:contribution>

<omm:contributor omm:type="email">user@dfki.de</omm:contributor>

<omm:date omm:encoding="ISO8601">2011-01-31T08:12:50+02:00</omm:date>

</omm:contribution>

<omm:title xml:lang="en">sample title</omm:title>

<omm:title xml:lang="de">Beispieltitel</omm:title>

<omm:title xml:lang="zh">样品称号</omm:title>

<omm:title xml:lang="ja">サンプルのタイトル</omm:title>

<omm:description xml:lang="en">sample description</omm:description>

<omm:description xml:lang="de">Beispielbeschreibung</omm:description>

<omm:description xml:lang="fr">description example</omm:description>

<omm:type>http://purl.org/dc/dcmitype/Dataset</omm:type>

<omm:subject>

<omm:tag omm:type="ontology" omm:value="http://o.org/def.owl#ManufacturerData" />

<omm:tag omm:type="ontology" omm:value="http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ontologies/v1/phase.owl#Production" />

<omm:tag omm:type="text" omm:value="ingredients" />

<omm:tag omm:type="text" omm:value="norms">

<omm:tag omm:type="text" omm:value="din">

<omm:tag omm:type="text" omm:value="e12" />

</omm:tag>

</omm:tag>

</omm:subject>

<omm:link omm:type="url" omm:hash="d32b568cd1b96d459e7291ebf4b25d007f275c9f13149beeb782fac0716613f8">http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/samples/p1/ext.xml</omm:link>

<omm:payload omm:encoding="base64">(...)</omm:payload>

</omm:block>

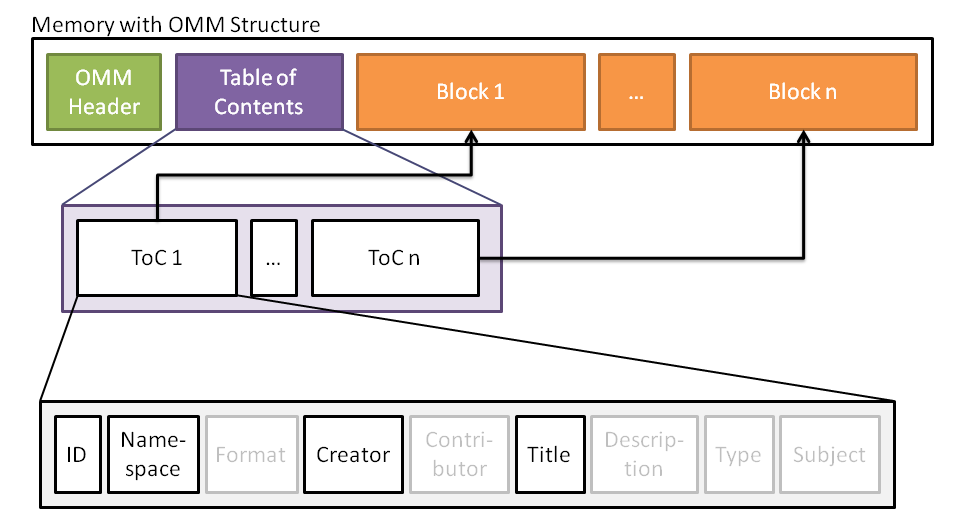

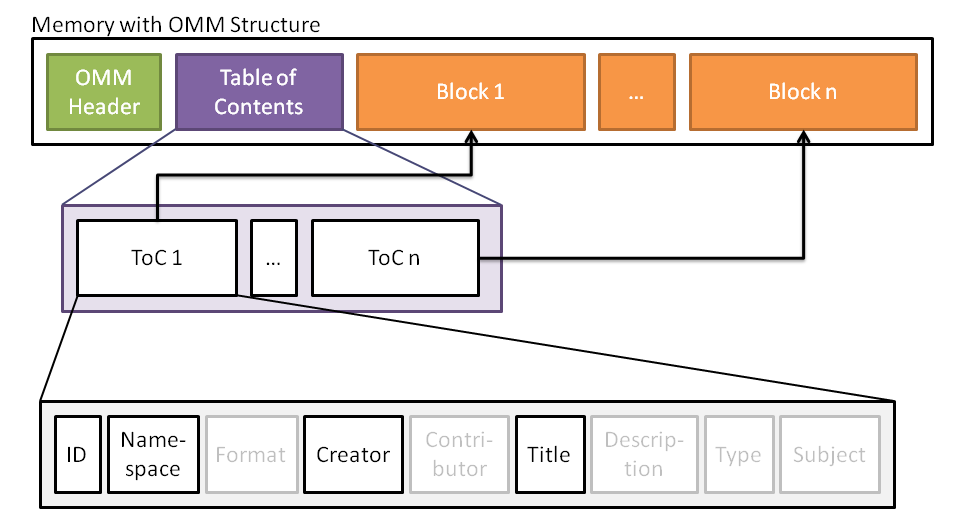

Figure 3: OMM Table of Contents

In addition to the already mentioned header and block structure of the OMM,

we provide an optional table of contents (ToC) strucuture. This allows most notably fast

and efficient reading of data storages with low speed, because it enables the system to

easily provide block information to end users without reading the entire memory content.

This means particulary for memory stores without random access capabilities, a parser is

able to retrive all block specific information at the beginning of the memory

just by reading the table of contents, without any need for

parsing the entire store, which may take some time (especially on low speed storages)

due to large sets of embedded data. To keep the ToC as small as possible only a few

block meta data are mandatory for the table of contents.

TODO: This requires a more intense elaboration of matters of efficiency.

In this section, the object memory model is introduced -

all crucial elements with their respective contents. There presence in

and relevance for the proposal has to be discussed. For illustration

purposes, the model is discussed on the basis an XML encoding, which is

employed for the folllowing use case descriptions as well.

(header according to OMM-XG Format Specification - ToC here or in Standardized Blocks?)

(todo)

The following use cases illustrate various applications of the OMM, here based on an XML encoding.

W3C prefers a tight relationship between proposed structures and use cases. Therefore, if a use case does not have a particular impact on the model (is redundant with another use case), we might decide to drop it. Furthermore, the similarity of some use cases (on the technical side) suggests combining these in a single description, which is then illustrated via example for one specific case.

In complex production processes there is a need to have the knowledge about every single process step. Production processes are error-prone. For more efficiency, to avoid errors and to increase product quality the real life process data will be recorded on an OMM linked with objects. These objects can be products as well as the machines and tools which are needed for production. The objects linked with OMM interact and communicate each other. So a product is able to communicate about a failure during a routing process, in consequence the next routing process cannot start. Besides of that such specific process information might be interesting for other companies or end users. Especially in industries such as Aerospace, Defense or Chemistry, there are requirements for such information for audits and for safety reasons.

The following production specific information might be stored in an OMM:

- Time stamps regarding specific production events

- Routing start / routing finish

- Production start / production finish

- Process history information

- Routing successful finished

- Routing finished with errors

- Quality check successful

- Unexpected events

- Process environment information

- Used tools

- Involved employees and their skills

- Energy consumption

The following example illustrates a production process with three successfully finished steps:

- Transportation to a workplace

- Production start and production finish

- Quality measurement finish

<omm>

<omm:block omm:id="3334">

<omm:namespace>http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ns/sample</omm:namespace>

<omm:title xml:lang="en">event log</omm:title>

<omm:log>

<omm:event omm:id="1">

<omm:action>Transport</omm:action>

<object class="this" />

<omm:status>OK</ omm:status>

<omm:time>2011-02-30T19:00:00+02:00</omm:time>

<omm:endTime>2011-02-30T19:01:00+02:00</omm:endTime>

<logger class="this" /> <!-- product detected event itself -->

</omm:event>

<omm:event omm:id="2">

<omm:action>Production</omm:action>

<omm:time>2011-02-30T19:03:00+02:00</omm:time>

<omm:endTime>2011-02-30T19:04:00+02:00</omm:endTime>

</omm:event>

<omm:event omm:id="3">

<omm:action>QualityCheck</omm:action>

<omm:time>2011-02-30T19:04:00+02:00</omm:time>

<omm:endTime>2011-02-30T19:06:00+02:00</omm:endTime>

</omm:event>

</omm:log>

</omm:block>

</omm>

Provenance information, Product Recommendation, Complex Transport.

...to bypass limitations in memory capacity, to allow for shared use of resources, to facilitate remote updates... - see Link and Link Set

In maintenance scenarios the concise identification of objects (assets) is an essential requirement for an effective maintenance process. The asset has to be easily identifiable with different IDs, because typically an asset has at least a serial number, an equipment ID and a location identification code. In addition to these identifiers assets may contain classifications and any number of valid values for each classification. An example are the Level of Maintenance classification codes (LMC codes), which define the importance of an asset in a specific domain. A maintenance technician uses the location identification code (e.g. +A10-F03) to identify the asset in a given context (e.g. plant), while a warehouse clerk needs the order number (e.g. 6SE6420-2AD22-2BA1) to get a spare part if the object must be replaced.

The OMM wants to support the usage of multiple identifiers and classifications. OMM offers a standardized OMM block (idBlock), which facilitates the storage of identifiers and classifications within the payload of the block as XML elements.

The following XML sample shows an OMM block with two different IDs which are specified with a type. The namespace identifies this block as ID block with a defined payload structure. The first ID-element contains a Bluetooth-address which is described by the type "Bluetooth". The second ID-element is an identifier for RFID tagging at the item-level (EPC SGTIN-96).

<omm:block omm:id="4711">

<!-- more meta data -->

<omm:namespace>http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ns/idBlock</omm:namespace>

<omm:title xml:lang="en">Object identifiers</omm:title>

<omm:creation>

<omm:creator omm:type="email">user@siemens.com</omm:creator>

<omm:date omm:encoding="ISO8601">2011-09-18T12:30:00+02:00</omm:date>

</omm:creation>

<omm:format>application/xml</omm:format>

<omm:payload>

<omm:id omm:type="bluetooth">01-02-03-04-05-06</omm:id>

<omm:id omm:type="SGTIN-96">0x30700048440cc8002e185623</omm:id>

</omm:payload>

</omm:block>

Future industrial and automation scenarios will involve decentralized production processes. For example, sub-contractors will be adapted on the fly. To support this novel flexibility it is desirable to collect all production-related product-specific information and to store them on the product parts as an OMM.

The OMM is suitable to describe the single productions steps and manipulation tasks that have to be performed on the individual product. Only this product-centered knowledge management approach, in which products communicate manipulation actions they require (“Fill in 3 pills of type A and close bin with cap”) or the dispatching strategies ("Prefer time critical jobs") to the production systems, enables the efficient design of robust and flexible decentralized production processes.

The simplest form of a decentralized production process can be implemented with an OMM that only holds static product specific information (e.g. product ID, product color, production timestamp, product quality, etc.). In each production step, the OMM information is read via respective OMM readers/sensors and the according manipulation actions and handling operations are derived in the process control and then performed on the product. Therefore, the product and its OMM information can be considered as passive while the control and handling algorithms are implemented in the process control (of each production module).

The following XML sample shows an OMM block which describes one OMM that specifies the production information for a personal medicament product (Personal Pill Blister) that is produced by ‘YourPersonalMeds Inc.’. The namespace identifies this block as structure block with a defined payload structure. The payload consists of two static variables that denote the pill type (SleppoPharm/PainReliefSuper) and number of pills that has to be filled in the blister. To obtain more information about the ingredients, date of expiry etc. of the individual pills, a reference to the according pharmacy is stored on the OMM.

<omm:block omm:id="125">

<!-- more meta data -->

<omm:namespace>http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ns/structureBlock</omm:namespace>

<omm:title xml:lang="en">Personal Pill Blister</omm:title>

<omm:creation>

<omm:creator omm:type="email">production@YourPersonalMeds.com</omm:creator>

<omm:date omm:encoding="ISO8601">2011-09-22T17:18:00+02:00</omm:date>

</omm:creation>

<omm:format>application/xml</omm:format>

<omm:payload>

<omm:id omm:type="SleepoPharm">3</omm:id>

<omm:id omm:type="url">http://www.yourpersonalmeds.com/infos/medicaments/sleepopharm</omm:id>

<omm:id omm:type="PainReliefSuper">1</omm:id>

<omm:id omm:type="url">http://www.yourpersonalmeds.com/infos/medicaments/painreliefsuper</omm:id>

</omm:payload>

</omm:block>

More complex scenarios might be implemented using procedural knowledge descriptions stored in the OMM, e.g., the OMM may contain more complex workflow descriptions that can be performed on the product itself. In this case the OMM describes a sequence of manipulations that can be performed on a product and therefore contains a higher form of knowledge. To support the integration of workflow descriptions standardized workflow models (formalized e.g. via XPDL) can be referenced with the OMM.

The following XML example shows an OMM block which describes a complex "packaging workflow". XPDL is used to model the workflow process via a standardized, XML-based notation. This is indicated by the format tag using the MIME type "application/x-xpdl". The authors stored the according XPDL document within the payload section of the OMM. Therefore, in this use case the OMM serves as a skeleton adding meta-information to the workflow description that can be directly stored on a product.

<omm:block omm:id="132">

<!-- more meta data -->

<omm:namespace>http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ns/structureBlock</omm:namespace>

<omm:title xml:lang="en">Packaging Workflow</omm:title>

<omm:creation>

<omm:creator omm:type="email">production@YourPersonalMeds.com</omm:creator>

<omm:date omm:encoding="ISO8601">2011-09-23T08:30:00+02:00</omm:date>

</omm:creation>

<omm:format>application/x-xpdl</omm:format>

<omm:payload>(... complete xpdl document ...)</omm:payload>

</omm:block>

In production scenarios component parts are often assembled to create a higher-value object. In the case of high-class objects such as automobiles, turbines, or computer tomographs it is reasonable to assume that even the components are valuable enough to have their own object memory. Examples could be the gearbox of an automobile or the low pressure section of a turbine.

While the new assembled object will get its own object memory, the information of the assembled components must stay accessible and changeable. For a reasonable handling it should be possible to build up a data structure which reflects the objects assembly. If parts of high-value products fail, these parts are repaired or exchanged. It must therefore be possible to alter the structure that reflects the objects assembly. Parts may be added or removed, connections between parts may be altered. If a part leaves the object (is dismantled) the object's memory should reflect its complete lifecycle including its life as a part of the object. I.e. a part should remember where it has been. As a counterpart the whole object should also be able to log the information about its dismantled parts. (E.g. the automobile knows that 2 engines have already been replaced. An engine should know that it has been built into 2 cars.)

The OMM supports the description of structured objects with a standardized block (structureBlock), which allows the description of structures with the means of relations (has_part, part_of,...) to the PrimaryId of the affected object memories.

The following XML sample shows an OMM block which describes two links to other OMMs. The namespace identifies this block as structure block with a defined payload structure. The two references in the payload are IDs with an additional relation attribute (has_part) which shows that the current object has two added parts. These parts in turn will have a structure block with an inverse relation (part_of) which is not visible in this example (because it is an element of another OMM).

<omm:block omm:id="678">

<!-- more meta data -->

<omm:namespace>http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ns/structureBlock</omm:namespace>

<omm:title xml:lang="en">Object Assembly History</omm:title>

<omm:creation>

<omm:creator omm:type="email">user@siemens.com</omm:creator>

<omm:date omm:encoding="ISO8601">2011-09-19T16:30:00+02:00</omm:date>

</omm:creation>

<omm:format>application/xml</omm:format>

<omm:payload>

<omm:id omm:relation="has_part" omm:type="url">http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/samples/part1</omm:id>

<omm:id omm:relation="has_part" omm:type="url">http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/samples/part2</omm:id>

</omm:payload>

</omm:block>

In industrial and automation scenarios it is desirable to have the ability to add information to object memories that should be unavailable for public reading because it is intended for some special user group only. For instance, object memory users may want to add information about confidential production processes, license-based data or information indented for bi-lateral communication.

The OMM wants to support such encrypted information, data providers should be enabled to easily add encrypted information. So it is possible to encrypt the payload data of each OMM block and flag this fact with the "encryption" attribute. This enables other application to skip this data block unless they are able decrypt the data which can be detected by the given creator and content meta data of this block.

The following XML sample shows a block with AES256 encrypted binary data encoded as Base64 text.

The combination of namespace and creator data allows users to detect whether they are able to decrypt this block or not (e.g. the namespace 'encSample' and the creator 'user@dfki.de' indicates the necessary AES key).

<omm:block omm:id="12345">

<!-- more meta data -->

<omm:namespace>http://www.w3.org/2005/Incubator/omm/ns/encSample</omm:namespace>

<omm:creation>

<omm:creator omm:type="email">user@dfki.de</omm:creator>

<omm:date omm:encoding="ISO8601">2011-09-15T12:30:00+02:00</omm:date>

</omm:creation>

<omm:format omm:encryption="aes256">application/octet-stream</omm:format>

<omm:payload omm:encoding="base64">cGxlYXN1cmUu</payload>

</omm:block>

- BPMN

- DUNS

- EPC

- EAN

- GTIN

- RFID

- XPDL