Accessibility basics

This page is very old and no longer the best information.

Please find current information on the W3C WAI website.

Introduction

When you create a web site, accessibility—making the web site usable by everyone, regardless of their ability or disability—should always be a central concern. So far in this course accessibility has always been implicit in all the examples you’ve seen, even if you didn’t realise it; in this Web Standards Curriculum article I’ll now look at accessibility explicitly, so you can understand fully what it is, why it is important, how to ensure that sites are accessible, and what guidelines exist to define accessible sites.

Before I look specifically at accessibility on the web, let’s start by looking at accessibility in general terms—after all, accessibility isn’t just a concern associated with web sites; it is potentially a concern with every service, object or technology you’ll come across in life.

Note that an associated topic to learn about is WAI ARIA—the Web Accessibility Initiative’s Accessible Rich Internet Applications initiative, which is basically a methodology to allow the creation of more accessible Ajax/JavaScript-powered applications. You can find a great introductory article covering ARIA on dev.opera.com.

Stella Systems have made a wonderful video that uses the text from the first part of this article as spoken word dialog, along with fantastic illustrations, and English and Russian subtitles. Watch the video on youtube. Thanks to Dmitry Nechiporenko, Anton Pashchenko, Lucy Stepanovska and Leonid Strorozhuk for this.

What is Accessibility?

Look around. Hopefully you will see some other people; if you don’t, why not take a quick walk? You’d probably enjoy it and it would do you good. None of the people you will see around you are the same—some have brown hair, some don’t. Some have blue eyes, some don’t. Some wear glasses, some don’t. None of us are completely alike. Some differences like hair or eye colour are cosmetic—they don’t significantly affect the way we live our lives. Some differences, like wearing glasses, do. Accessibility is a simple thing, a philosophy, although in some countries it is also part of the law.

Accessibility is treating everyone, no matter what their ability, the same.

I realise that this statement is open to interpretation. Most discussions of accessibility first talk about disability. This implies that people with a disability deserve special treatment. This isn’t what accessibility is about—it’s actually a symptom of the way people have traditionally built buildings, web sites, and pretty much everything else in fact.

When you build things with the assumption that everyone is the same as you, then they will always be wrong for some other people. People assume accessibility is about helping people with disabilities because retrofitted accessibility is very obvious in our societies. For example, a lot of buildings that started life with only steps have suddenly sprouted cheap ugly ramps. However, accessibility has long been a feature of military design. Why? because it is often critical for survival—at high g-forces jet fighter pilots can’t do the same things they can do on the ground. If aircraft designers didn’t take the needs of pilots in both high and low gravity environments into account then there would be a lot more plane crashes.

So, what does this mean for web site developers? The short answer is that you need to try to be more aware of the needs of the entire audience that might look at your site. A longer answer might require you to learn a little about the differing levels of ability people can have, and how they use computers. By applying the techniques outlined in this curriculum and other related articles you can create sites that work with many forms of interaction. Your web sites will be usable by people whether they:

- Are blind or severely visually impaired, and listen to web sites using a screen reader, or feel them on a braille display.

- Are shortsighted, and blow them up to 200% font size.

- Have motor disabilities so can’t use their hands to manipulate a mouse, and therefore use a pointing stick to manipulate the keyboard, or an eye pointer to manipulate the web site.

- Use trackballs, or other more unusual types of computer control system.

Don’t worry about the specific details of these interactions— we’ll go through those step by step next.

Why is Accessibility important?

Accessibility is important for one big reason and a whole lot of little ones. The main one is that we are all different and yet we all have an equal right to use web sites, but there are lots of other reasons why you should make accessibility considerations a part of how you build web sites:

- In some countries it’s the law.

- You don’t want to exclude any potential customers/visitors from using your site.

- Accessible sites tend to rank higher on search engines.

- You are demonstrating good ethics—something that customers will value.

- Once you build web sites with web standards it hardly requires any extra effort to make it accessible, which gives so many benefits; there is also a lot of crossover between sites being more accessible, and sites being more compatible with mobile phone browsers—another circumstance that makes web site harder to use, although for different reasons. In fact, some work has been done on analysing the relationship between web accessibility and mobile web development best practices—see the WAI "Web Content Accessibility and Mobile Web" page for more.

- Techniques that help people with disabilities benefit all users.

Now I will move on to look at some of these points in more detail.

The legalities of accessibility

Note: it’s important to understand the basics of the legal stuff but unless you are a lawyer and really know what you are talking about, you should take extreme care giving an opinion about legal issues.

In the UK, under the DDA, it is illegal to discriminate against disabled people when recruiting and employing people, and providing services or education. Discrimination is defined as not making “reasonable adjustments” to support everyone, regardless of (dis)ability. This applies of course to making services or education available via the medium of web sites.

In the USA and European Union there are also requirements for Governmental web sites. In the USA, federal government (and some state government) web sites are expected to abide by Section 508. Section 508 is a document that tries to define what the minimum requirements are to achieve accessiblity. Section 508 covers more than just web sites; it also deals with any other technology that might be used by a federal employee. In Europe the European Commission has recognised the W3C’s Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) and recommended it for use with all member states. The WAI produces guidelines for web sites, web authoring tool manufacturers and web browsers (for example, the WCAG, which I’ll look at later on.)

Potential Markets

When you only make web sites (or anything else) for one specific type of person you are excluding other types of people even if you don’t realise it, and these people can easily add up to a significant (if not a majority) market share. In 2000 the UK supermarket chain Tesco started a project to make a separate version of their online grocery site specifically targetting people with visual impairments. It was noted by Julie Howell of the RNIB that “Work undertaken by Tesco.com to make their home grocery service more accessible to blind customers has resulted in revenue in excess of £13m per annum, revenue that simply wasn’t available to the company when the web site was inaccessible to blind customers.” So if Tesco hadn’t considered people with visual impairments they would have been missing out on a market of customers that was worth at least £13 million.

The core lesson here is that people of all abilities need the same services; groceries, taxis, electricity; and enjoy the same things; films, music, bars. Assuming that someone’s personal situation in life changes their ability or desire to participate in all aspects of society has been shown to be a mistake time and time again.

Search Engines

Search engines are not people. Often when people build web sites they do it without considering how they are going to be found on Google, Yahoo, etc. Search engines are just computer programs, and they can only use information they can understand to index your site. This makes them much like the screen readers that a person with a visual impairment might use.

The most obvious example of how this affects web design is images. Computers display images by having a list of what colour every pixel is and sending that information to the monitor. If you put an image on a web page that contains some text, for example a logo, the computer has no idea what that text says or even that the image contains text. In HTML the image element contains a way to describe in text the contents of an image, the alt attribute. You should provide text to describe all non-decorative images on your site, and you certainly shouldn’t represent whole paragraphs of text as images (or Flash for that matter)—blind people and search engines won’t have a clue what the text says! As a result, your search engine ranking (ie how easy it is to find your web site using search engines such as Google) will suffer and you’ll be needlessly missing out on a valuable market.

Ethics and branding

While everyone should support Accessibility, it doesn’t mean that everyone does. By supporting accessibility you are acting in the best interests of the community. This is something you can be proud of—showing that you care about everyone in society can only enhance a brand image. As professionals it’s our job to try and produce the best quality output we can. In a society that values us as individuals it’s important to not exclude someone because they have different needs.

By making responsible choices in policy and genuinely demonstrating that you are implementing those policies you can create an extremely positive brand image. Companies that show that they care about their customers will retain much more loyalty than those that don’t.

Designing with Accessibility in mind

The key to accessibility is thinking about a problem and knowing you are going to solve it for more than one kind of user. If you try to treat accessibility like something you can bolt on at the end then you will get a nasty-bolted-on-at-the-end thing. It’ll take longer, won’t work as well and look damned ugly.

The best way to achieve a well-engineered solution is to design with all the requirements in mind from the start. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t change your plan or add some things you missed, but you should try to be aware of what the complete problem you are trying to design for is. In the case of web sites this means creating a solution usable by all your users including those who may not be able to use a mouse, or a keyboard, or a monitor, etc.

Interoperability requirements

Interoperability requirements are especially likely to vary from situation to situation.

New technology is often introduced without support for accessibility. For example, Microsoft’s new Silverlight plugin does not expose information via the accessibility APIs used by screen readers and other assistive technology, although such support is planned for the future.

Where support is theoretically present it can take time for assistive technology to make use of it. Newer screen readers work much better with JavaScript-triggered updates to HTML structures than older screen readers, for instance.

Even when long-established, accessibility support may continue to differ across platforms. For example, the Adobe Flash Player plugin has long exposed information to the Windows accessibility API, but not to the Apple or GNOME equivalents.

There also tends to be a lag between the arrival of supporting technology and its wide distribution. Whereas browsers and plugins nowadays tend to be free, whereas mainstream assistive technology can be very expensive. For example, one of the most popular screen readers is Freedom Scientific’s JAWS for Windows. A new version comes out roughly every year. JAWS Professional retails for $1,095, and even if you spend $200 to get a Software Maintenance Agreement for the next two versions, upgrades will still cost $500 or more. Consequently, although the latest release is version 9, you can still find lots of JAWS users using older versions.

So when you aim to build websites for the public Web, you need to take some account of interoperability with a highly varying client-side user/technology combination. There are four approaches:

- Progressively enhance your web site, testing for support as you go.

- Allow users to turn off problematic enhancements.

- Provide alternate versions with the same content or functionality.

- Advise your clients on what technologies they need to support and give examples of companies that do support those technologies.

Within intranets, backwards compatibility and variety is less of a concern. A given organization might be able to guarantee that all employees with disabilities will have access to assistive technology with decent support for DHTML, for example. In such circumstances, and with proper testing with the provided assistive technology, it would be reasonable to treat JavaScript as a baseline.

Forward compatibility and cross-platform compatibility are still issues however, so open, standard technologies should be preferred over proprietary, non-standard technologies.

For example, you might be developing an intranet training application for a large corporation. They have asked you to ensure the application is accessible, but have not specified a standard to which you must conform. You speak to their IT department and find out that everyone has the latest version of Internet Explorer, with JavaScript enabled, Flash installed and enabled, and will be provided with modern assistive technology they need to support those items. Now, even if the company moves to Unix-based platform, there will be assistive technology that supports JavaScript, but Flash text and controls are only accessible on Windows. You can safely make scripting and Flash a baseline requirement for your application. But you decide to only use Flash for playing video, and to build the control sets for the Flash video from web standards, since Flash controls are only accessible to assistive technology on the Windows platform. That way, the application would still be accessible even if the company migrated to Unix.

Organizational IT policies may change, and the best attempts to make JavaScript functionality operable and exploit the accessibility feature-sets of plugins may fail, so even if you have a technology baseline progressive enhancement from a core HTML layer is still a good idea.

Features of an accessible web page

In this section I will go through the different accessible features of a web site—that is, what an accessible web site should contain. I’ll explain each one in detail.

Semantic structure

One of the foundations of web standards is the use of semantic structure in HTML. Semantic structure is also extremely important for accessibility. This is because it provides the framework for the information on the page. When people can’t see the visual style of the page, the semantic structure helps to indicate a number of things to them. It can indicate their position in the heirarchy of the document and the ways they can interact with the different elements of the page, as well as providing emphasis to textual content in the right places.

A good example of how the semantic stucture of a document is important to accessiblity is navigation. A well structured navigation menu is a list of items. You can mark this up as an HTML list:

<ul> <li>Menu Item 1</li> <li>Menu Item 2</li> <li>Menu Item 3</li> </ul>

By having navigation menus structured as lists it is easy to let someone using a screen reader, who can’t see the list, know it’s a list. This is because their screen reader tells them it’s a list. If you don’t use list markup then the screen reader has no way of knowing it's a list and telling the user.

You can find more information on how to use the correct semantics in your HTML in many of the earlier articles in the course, mainly the ones that cover HTML.

Alternative content

As mentioned in the section about search engines, ensuring that there is an accessible alternative to content and navigation is essential. Text is considered the universal currency of content with one alternative, as you’ll see below. Text can be easily read aloud by a screen reader, made bigger or smaller, have its contrast easily altered and many other transformations. It’s because it is so easy to manipulate text that more exotic forms of content should have a text-based alternative to them. Some formats, like the newer versions of Flash, have text access built into them so that the textual content within them can be accessed directly without needing to provide an alternative for the whole medium.

The one disability group that a text alternative can’t necessarily support is people with cognitive disabilities. The difficulty with supporting people with cognitive disabilities is that often they require different content, rather than the same content in a different medium. This is not to suggest you shouldn’t try. Simplifying the language and terminology used on your site benefits everyone. Groups like the Plain Language Commission have been advocating a “plain speech” approach to the material companies use to inform their customers of important information such as legal requirements and terms and conditions. They provide a plain english lexicon containing terms that can be used to help communicate effectively using the simplest language possible.

How should you implement text alternatives on your site? The first step is to identify things that aren’t already text. In HTML there are only so many things that aren’t already text. Images are the most obvious ones. Here is an example of an accessible use of an image:

<code><p>An interesting piece of art is Michelangelo’s “God creates Adam” <img src="images/adam.jpg" alt="A painting of a man reaching up to touch God’s hand reaching down. It is cracked with age." longdesc="adam.html">.</p></code>

The image in this example is an integral part of the content. The alt attribute contains a short description of the image for people (or search engines) that might not be able to see the image correctly. The longdesc attribute allows you to link to an HTML page containing a full description of the image. This is generally only used to describe complex images that are used as central content. It also suffer from poor support in browsers. Most of the time you will only use the alt attribute.

When images are used for things other than content, such as navigation, or purely visual decoration you should treat them differently from content images. Images used to make buttons or page navigation look more attractive should have an alt attribute that matches the text in the image. The alt attribute simply functions as an easy way to allow the computer to read the text contained in the image (and hence read it to the user of a screen reader).

In the case of purely decorative images, images used for tracking adverts, or any other image that a user wouldn’t be expected to be interested in or interact with, you should set the alt attribute to be empty. This does not mean omitting the attribute but setting alt="". This is because of a tactic screen readers have used to help their users cope with very inaccessible pages. When an image doesn’t have an alt attribute, especially when it’s part of a link, the screen reader reads the URL of the image to the user. This is so they can guess what the image is from the URL, for example if the image is named something like add_to_cart.gif. Therefore, you should set alt="" on images that you know the user won’t be interested in, so that screenreaders won’t read out every image’s URL, which could be rather frustrating for the screen reader user.

Not all forms of content are as simple as an image. More complex media like Flash (Flash files can be whole web sites in themselves) or movies require more complex descriptions. The most recent versions of Flash allow you to provide text alternatives for the items within the Flash movie, just like in HTML.

Defining interaction

A lot of today’s web involves the use of technologies in addition to HTML. Even something as basic as CSS can be used in ways that make a page or interaction much less accessible. The key to accessibility in interaction is starting with the simplest interactions and using those as the building blocks of more complex interactions.

Note that the point of this example is to make you think about the role different things on web pages have. To ensure that they are accessible, they must be semantically sound in terms of both the HTML elements used, and the visual metaphor used. If you find this confusing, then reread the example a few times, and also look a few menus and other web page components, while thinking about not only if the correct HTML is used, but also if the look and feel of the component successfully makes sense in terms of what its functionality is. You wouldn’t expect a web page visitor to search using a text box labeled “enter your mail address to sign up for this newsletter”, nor would you expect a sighted visitor to be able to find content of interest if all the headings were styled just like regular text (similarly, you wouldn’t expect a blind user to find content of interest if all the “headings” were actually just paragraphs made to look bigger using CSS or font elements).

A good example of this is the commonly used visual metaphor of tabs. The tab metaphor is drawn from ring binders indexed by topic. This has been translated to computers to allow a single area on the screen to display the information from various topics represented by tabs connected to that area—you can see a good example of tabs on dev.opera.com—look at them at the top of the page. So far it is all reasonably simple. The problem lies in the technologies used to create tabs—they are often implemented using JavaScript.

As soon as tabs are used as part of an interaction more complex than allowing the user to select the information the original metaphor has been broken, but often the same code is still used to represent the tabs. In the example below the HTML shows what a tab control that displays information looks like:

<div class="tabcontrol">

<div class="hd">

<ul>

<li><a href="#dogs" class="selected">Dogs</a></li>

<li><a href="#cats">Cats</a></li>

<li><a href="#fish">Fish</a></li>

</ul>

</div>

<div class="bd">

<p id="dogs" class="selected">Some information about dogs. The dogs tab is the default tab.</p>

<p id="cats">Some information about cats.</p>

<p id="fish">Some information about fish.</p>

</div>

</div>

In this example the selected class would be used to specify which tab needs to show the “tab to the front” graphic, for example check out the “Articles” tab at the top of this page which uses this method.

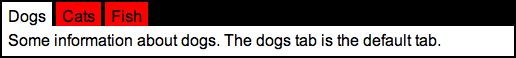

This structure is fine for informational content. In this example, the class of selected would be used to signify which tab is the active tab, ie, the one that is open and displaying its information; the others would be closed (ie, their paragraphs hidden) until their corresponding links are clicked on. The dogs tab is the default active tab, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A simple tab control showing the dogs tab, the default, active.

Once another link is clicked on (as shown in Figure 2) JavaScript would then be used to dynamically move the class="selected" to that link, at which point style would be applied to that tab to display it, and the one that was previously displayed would be hidden.

Figure 2: Now a different link has been clicked on, its corresponding tab becomes active.

you will find real working examples of this kind of control in some of the later JavaScript chapters, to be published soon.

It has also become common to use tabs to allow users to select different kinds of searches. In this case the concept starts to break down if you try to reuse the style of code from the previous example:

<div class="tabcontrol">

<div class="hd">

<ul>

<li><a href="#dogs" class="selected">Dogs</a></li>

<li><a href="#cats">Cats</a></li>

<li><a href="#fish">Fish</a></li>

</ul>

</div>

<div class="bd">

<form id="dogs" class="selected" action="search.html" method="GET"><div><label for="dogsearch"><input type="text" name="dogsearch" id="dogsearch"><input type="submit" value="Search for Dogs"></div></form>

<form id="cats" action="search.html" method="GET"><div><label for="catsearch"><input type="text" name="catsearch" id="catsearch"><input type="submit" value="Search for cats"></div></form>

<form id="fish" action="search.html" method="GET"><div><label for="fishsearch"><input type="text" name="fishsearch" id="fishsearch"><input type="submit" value="Search for fish"></div></form>

</div>

</div>

Employing the same code structure no longer makes sense—in this case you get the same form elements repeated again and again in order to fit into the concept of replacing content, which is a waste of markup. Instead of thinking visually it’s important to think about the interaction itself. In this example, rather than selecting new information to view the tabs you should be changing the interaction the user has with the search form. In effect the only thing a tab should be doing is selecting what type of animal the user is searching for. If you put this into practice you can create a much better interaction for all users of the site, with cleaner, easier to maintain markup:

<form action="search.html" method="GET">

<fieldset>

<legend>Search within:</legend>

<ul>

<li><label for="dogs">Dogs</label><input id="dogs" type="radio" name="animal" value="dog" checked></li>

<li><label for="cats">Cats</label><input id="cats" type="radio" name="animal" value="cat"></li>

<li><label for="fish">Fish</label><input id="fish" type="radio" name="animal" value="fish"></li>

</ul>

</fieldset>

<input type="text" id="searchfield" name="search">

<input type="submit" value="Search">

</form>

By creating the interaction first, the markup is cleaner and all users of the site get the best experience possible. When we started by extending a visual metaphor we quickly broke the interaction and created some horrible markup based on the assumptions of the previous example. Had we been using AJAX to insert the content instead of having it all on the page, it would have been even worse. Then users without JavaScript would have had to load an entirely new page to get a search form for cats or fish. By thinking about the basic interaction first (rather than the visuals) you can simplify the problem. Now we can still maintain a tab metaphor (albeit with a bit of styling and script) while only using one form for all the searches.

This is the core to understanding how to do accessible interaction. One of the great things about HTML is that the hard work of figuring out how to make the interactions in HTML accessible has already been done. As long as you don’t use the technologies on top of HTML to break the metaphor you can make most things work for most people without much effort.

Standards for Accessibility

In this section I will review some of the standards and guidelines available that aim to define web accessibility, and help web developers to create accessible sites. Most of these systems include some kind of check list system so developers can check how their sites match up to different accessibility criteria.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0

The W3C is one of the primary standards bodies on the internet. Their Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) published the first version of their guidelines for making web sites accessible in May 1999. The Web Content Accessibility Guidlines (WCAG) are the most widely used standard for Accessibility on the Web. The use of WCAG 1.0 has been suggested or mandated by a number of governmental bodies including the EU and the Italian government.

WCAG 1.0 is a set of 14 Guidelines that try to encapsulate the goals necessary to achieving an accessible page. Within each guideline are a number of checkpoints, which are the real meat of the document. While the guidelines explain the concepts the authors had in mind, the checkpoints are what are used to validate conformance. Each of the checkpoints are ranked from priority 1 to priority 3, to illustrate how important they are. In order to conform to WCAG 1.0 you must complete every priority 1 checkpoint. Adhering to all of the priority 1 checkpoints gives you a conformance rating of “A”. If you meet all the priorty 2 checkpoints as well then you conform to “AA”. Should you meet all the priority 1, 2 and 3 checkpoints then you would conform to “AAA”, which is the highest rating.

In reality WCAG 1.0 is a little old-fashioned. A lot of companies start by conforming to level “A” or “AA” and then adding in some common sense and real user testing. WCAG 1.0 is a good starting point, but you should be looking towards some of the newer standards, especially if you use a lot of JavaScript, or other technologies that matured after 1999, when the WCAG 1.0 was released.

Another important thing to note about the WCAG 1.0 standard is it was designed to be part of a suite of 3 documents. Another one covered “User Agents”, which describes browsers (like Opera) and any extra technology people might need to use the web (like screen readers). The third covered authoring tools such as Dreamweaver or content management systems—it aims to try to make these tools do more of the work of making pages accessible. Unfortunately this vision hasn’t played out and the only standard out of the 3 to be widely adopted was WCAG 1.0. This means that often the expectations of WCAG 1.0 regarding user agents aren’t met, and very little of the burden of making web sites accessible is taken off you by authoring tools. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use WCAG 1.0; it simply means that it only meets part of accessiblity and is not a complete solution.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0

Since publishing WCAG 1.0, the W3C has been working on WCAG 2.0. This updated version of the standard is still in draft at the time of writing. Subject to the process of the W3C it will probably be a published standard by early 2009.

WCAG 2.0 is slightly different in it attempts to be more technology-agnostic than WCAG 1.0, ie it could be applied to HTML, CSS, Flash, etc. WCAG 2.0 is based on 4 principles for accessibility. These are:

Perceivable People can access the content through a medium available to them. For example people who can’t see should be able to hear the content Operable People can interact with the web application or content. Understandable The content and user interface is understood by the people who are using it. Robust Any solution provided should be using widely available on different platforms or systems. This is to stop people inventing solutions that the majority of people wouldn’t be able to use because the hardware/software is restricted or prohibitively expensive. It’s important to note that web sites aren’t expected to fulfill all of these requirements. The technology a user has should do some of the work too. For example it is expected that a screen reader will read pages to people who need it, rather than every web site providing an audio version of the content. However, the web site is expected to provide pages that can be read using common screen reading technology in order to make this possible. This difference is important, as it’s the difference between a web site with an “accessibility widgets” (like a button to make the fonts a bit bigger) and a web page that will work in a multitude of different situations (eg varying browsers and devices that would be impossible to anticipate).

WCAG 2.0 also differs from WCAG 1.0 in the approach to technology. Since the standard is more technology-agnostic and deals with concepts about accessibility rather than concrete technical details it’s important to pay attension to the surrounding documents to the standard. The “standard” document of WCAG 2.0 will provide the understanding but the “techniques” document provides solid implementable pieces of information for the developer. This is broken up into “general” techniques (technology ambiguous) and specifics for individual W3C technologies. The W3C doesn’t write documents for proprietary technologies so you’ll have to find techniques for technologies like Flash and Silverlight from other sources.

Section 508

Section 508 is an extension to the American Workforce Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The version of Section 508 that became law in 1998 created a process that must be followed during US Federal government procurement. This means that all government agencies in the USA that are funded by federal money must comply with the process and guidelines set down in Section 508. These guidelines cover both web accessiblity and other accessibility issues relating to computers and electronic communication. Whatever else you might have heard, there is no federal law mandating the use of Section 508 beyond the organisations described above. However, some US states and companies use Section 508 to define “accessibility” for their own procurement processes.

The part of Section 508 that covers web accessibility is Subpart B § 1194.22. Clause 1194.22 is split into 16 requirements labeled a-p. The first 11 requirements (a through k) are stated as being directly equivalent to parts of WCAG 1.0. The requirements and their equivalents in WCAG 1.0 are listed in a reference table in the section 508 document. All the other requirements of Section 508 should be met by WCAG 2.0 with one exception. Requirement m refers to Section 508 Subpart B § 1194.21. This requirement has a partial equivelent in the Robust principle of WCAG 2.0.

As of the time of writing of this article there was an ongoing investigation in to a new version of section 508 by the Telecommunications and Electronic and Information Technology Advisory Committee (TEITAC). TEITAC presented its findings to the assessment board for Section 508 in April 2008.

Other standards

Another important standard being developed by the W3C is the WAI-ARIA standard. This stands for Web Accessibility Initiative—Accessible Rich Internet Applications. It is a suite of documents that defines how to make complex web applications that use technologies like HTML, JavaScript and AJAX accessible. This standard is officially supported by the upcoming/current versions of most of the major browsers in the market place: Opera 9.5+, Internet Explorer 8+ and Firefox 3+.

There are many other standards for web accessibility too numerous to go into much detail about. The W3C maintain an excellent list of international policies relating to web accessibility—this is a great resource to help find the policy documents relating to your local government.

Summary

Accessibility is an important topic for both economic and social reasons. It is not a feature of a web site, but a measure of the quality it was built with. If you consider your site's audience as you are building it (and before) you will build more accessible pages with all the benefits that this brings. There are a number of well-known guidelines to help you—by conforming to those guidelines you can ensure that what you have built meets expert criteria in making your pages accessible.

Exercise questions

- Give 3 reasons why it’s important to build accessible web sites.

- Use the internet to research the accessibility laws in your country and make a list of any laws that you think would apply to your web sites. Make sure you include if they ask you to use any web standards such as WCAG or Section 508.

- Explain how accessibility is important to search engine optimisation.

- Create an example of an accessible use of alternative content using some of your own content, such as a photo.

- Use the internet to research how you would make a technology like Flash or Silverlight accessible and write a comparison between making them accessible, and how you make HTML accessible.

- Explain how you would design an interaction on a web page to be accessible. Create the step by step instructions for creating a tree control (you don’t actually have to make it).

Note: This material was originally published as part of the Opera Web Standards Curriculum, available as 25: Accessibility basics, written by Tom Hughes-Croucher. Like the original, it is published under the Creative Commons Attribution, Non Commercial - Share Alike 2.5 license.

Next: Accessibility: Accessibility testing.