Chapter 7: Coordinate Systems, Transformations and Units

Contents

7.1. Introduction

For all media, the SVG canvas

describes "the space where the SVG content is rendered." The

canvas is infinite for each dimension of the space, but

rendering occurs relative to a finite rectangular region of the

canvas. This finite rectangular region is called the SVG viewport.

For visual media

([CSS21], section 7.3.1)

the SVG viewport is the viewing area where the user sees the SVG content.

The size of the SVG viewport (i.e., its width and height) is

determined by a negotiation process (see Establishing the size of the initial

viewport) between the SVG document fragment and its parent

(real or implicit). Once that negotiation process is completed,

the SVG user agent is provided the following information:

- a number (usually an integer) that represents the width

in "pixels" of the viewport

- a number (usually an integer) that represents the height

in "pixels" of the viewport

- (highly desirable but not required) a real number value

that indicates the size in real world units, such as

millimeters, of a "pixel" (i.e., a px unit

as defined in CSS 2.1

([CSS21], section 4.3.2)

Using the above information, the SVG user agent determines

the viewport, an initial viewport coordinate system and an

initial user coordinate system

such that the two coordinates systems are identical. Both

coordinates systems are established such that the origin

matches the origin of the viewport (for the root viewport, the

viewport origin is at the top/left corner), and one unit in the

initial coordinate system equals one "pixel" in the viewport.

(See Initial

coordinate system.) The viewport coordinate system is also

called viewport space and the user coordinate system is also called

user space.

Lengths in SVG can be specified as:

- (if no unit identifier is provided) values in user space

— for example, "15"

- (if a unit identifier is provided) a length expressed as

an absolute or relative unit measure — for example, "15mm"

or "5em"

The supported length unit identifiers are: em, ex, px, pt,

pc, cm, mm, in, and percentages.

A new user space (i.e., a new current coordinate system) can

be established at any place within an SVG document fragment by

specifying transformations in the

form of transformation matrices

or simple transformation operations such as rotation, skewing,

scaling and translation. Establishing new user spaces via coordinate system

transformations are fundamental operations to 2D graphics

and represent the usual method of controlling the size,

position, rotation and skew of graphic objects.

New viewports also can be established. By establishing a new

viewport, you can redefine the meaning of percentages units

and provide a new reference rectangle for "fitting" a graphic

into a particular rectangular area. ("Fit" means that a given

graphic is transformed in such a way that its bounding box in

user space aligns exactly with the edges of a given

viewport.)

7.2. The initial viewport

The SVG user agent negotiates with its parent user agent to

determine the viewport into which the SVG user agent can render

the document. In some circumstances, SVG content will be

embedded (by reference or

inline) within a containing document. This containing

document might include attributes, properties and/or other

parameters (explicit or implicit) which specify or provide

hints about the dimensions of the viewport for the SVG content.

SVG content itself optionally can provide information about the

appropriate viewport region for the content via the ‘width’

and ‘height’ XML attributes on the outermost svg element.

The negotiation process uses any information provided by the

containing document and the SVG content itself to choose the

viewport location and size.

The ‘width’ attribute on the

outermost svg element

establishes the viewport's width, unless the following

conditions are met:

- the SVG content is a separately stored resource that is

embedded by reference (such as the ‘object’ element in XHTML [XHTML]), or the SVG

content is embedded inline within a containing document;

- and the referencing element or containing document is

styled using CSS [CSS21] or

XSL [XSL];

- and there are CSS-compatible positioning properties

([CSS21], section 9.3)

specified on the referencing element (e.g.,

the ‘object’ element) or on

the containing document's outermost svg element that are sufficient

to establish the width of the viewport.

Under these conditions, the positioning properties establish

the viewport's width.

Similarly, if there are

positioning properties

specified on the referencing element or on the

outermost svg element that are

sufficient to establish the height of the viewport, then these

positioning properties establish the viewport's height;

otherwise, the ‘height’ attribute

on the outermost svg element

establishes the viewport's height.

If the ‘width’ or ‘height’

attributes on the outermost svg element

are in user units (i.e., no unit

identifier has been provided), then the value is assumed to be

equivalent to the same number of "px" units (see Units).

In the following example, an SVG graphic is embedded inline

within a parent XML document which is formatted using CSS

layout rules. Since CSS positioning properties are not provided

on the outermost svg element,

the width="100px" and

height="200px" attributes

determine the size of the initial viewport:

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes"?>

<parent xmlns="http://some.url">

<!-- SVG graphic -->

<svg xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'

width="100px" height="200px" version="1.1">

<path d="M100,100 Q200,400,300,100"/>

<!-- rest of SVG graphic would go here -->

</svg>

</parent>

The initial clipping path for the SVG document fragment is

established according to the rules described in The initial clipping

path.

7.3. The initial coordinate system

For the outermost svg element, the SVG user

agent determines an initial viewport coordinate system and an

initial user coordinate system such that the

two coordinates systems are identical. The origin of both

coordinate systems is at the origin of the viewport, and one

unit in the initial coordinate system equals one "pixel" (i.e.,

a px unit as defined in CSS 2.1

([CSS21], section 4.3.2)

in the viewport. In most cases, such as

stand-alone SVG documents or SVG document fragments embedded

(by reference or

inline) within XML parent documents where the parent's

layout is determined by CSS [CSS21] or

XSL [XSL], the initial viewport

coordinate system (and therefore the initial user coordinate

system) has its origin at the top/left of the viewport, with

the positive x-axis pointing towards the right, the positive

y-axis pointing down, and text rendered with an "upright"

orientation, which means glyphs are oriented such that Roman

characters and full-size ideographic characters for Asian

scripts have the top edge of the corresponding glyphs oriented

upwards and the right edge of the corresponding glyphs oriented

to the right.

If the SVG implementation is part of a user agent which

supports styling XML documents using CSS 2.1 compatible

px units, then the SVG user agent should get its

initial value for the size of a px unit in real world

units to match the value used for other XML styling operations;

otherwise, if the user agent can determine the size of a

px unit from its environment, it should use that

value; otherwise, it should choose an appropriate size for one

px unit. In all cases, the size of a px must

be in conformance with the rules described in CSS 2.1

([CSS21], section 4.3.2).

Example InitialCoords below

shows that the initial coordinate system has the origin at the

top/left with the x-axis pointing to the right and the y-axis

pointing down. The initial user coordinate system has one user

unit equal to the parent (implicit or explicit) user agent's

"pixel".

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="300px" height="100px" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<desc>Example InitialCoords - SVG's initial coordinate system</desc>

<g fill="none" stroke="black" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="1.5" x2="300" y2="1.5" />

<line x1="1.5" y1="0" x2="1.5" y2="100" />

</g>

<g fill="red" stroke="none" >

<rect x="0" y="0" width="3" height="3" />

<rect x="297" y="0" width="3" height="3" />

<rect x="0" y="97" width="3" height="3" />

</g>

<g font-size="14" font-family="Verdana" >

<text x="10" y="20">(0,0)</text>

<text x="240" y="20">(300,0)</text>

<text x="10" y="90">(0,100)</text>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

7.4. Coordinate system transformations

A new user space (i.e., a new current coordinate system) can

be established by specifying transformations in the form of a ‘transform’

attribute on a container element or graphics element or a

‘viewBox’ attribute on an

‘svg’,

‘symbol’,

‘marker’,

‘pattern’ and the

‘view’ element.

The ‘transform’ property and ‘viewBox’ attribute transform user

space coordinates and lengths on sibling attributes on the

given element (see

effect of the ‘transform’ attribute on sibling attributes

and effect

of the ‘viewBox’ attribute on

sibling attributes) and all of its descendants.

Transformations can be nested, in which case the effect of the

transformations are cumulative.

The section "effect of the transform attribute on sibling attributes"

has been removed since we now reference the ‘transform’ property, but we probably

should still include a similar section on how the property affects attributes on the

element.

Example OrigCoordSys below

shows a document without transformations. The text string is

specified in the initial coordinate

system.

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="400px" height="150px"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.1">

<desc>Example OrigCoordSys - Simple transformations: original picture</desc>

<g fill="none" stroke="black" stroke-width="3" >

<!-- Draw the axes of the original coordinate system -->

<line x1="0" y1="1.5" x2="400" y2="1.5" />

<line x1="1.5" y1="0" x2="1.5" y2="150" />

</g>

<g>

<text x="30" y="30" font-size="20" font-family="Verdana" >

ABC (orig coord system)

</text>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

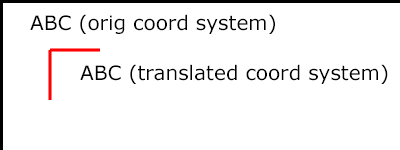

Example NewCoordSys

establishes a new user coordinate system by specifying transform="translate(50,50)" on the

third ‘g’ element below. The

new user coordinate system has its origin at location (50,50)

in the original coordinate system. The result of this

transformation is that the coordinate (30,30) in the new user

coordinate system gets mapped to coordinate (80,80) in the

original coordinate system (i.e., the coordinates have been

translated by 50 units in X and 50 units in Y).

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="400px" height="150px"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.1">

<desc>Example NewCoordSys - New user coordinate system</desc>

<g fill="none" stroke="black" stroke-width="3" >

<!-- Draw the axes of the original coordinate system -->

<line x1="0" y1="1.5" x2="400" y2="1.5" />

<line x1="1.5" y1="0" x2="1.5" y2="150" />

</g>

<g>

<text x="30" y="30" font-size="20" font-family="Verdana" >

ABC (orig coord system)

</text>

</g>

<!-- Establish a new coordinate system, which is

shifted (i.e., translated) from the initial coordinate

system by 50 user units along each axis. -->

<g transform="translate(50,50)">

<g fill="none" stroke="red" stroke-width="3" >

<!-- Draw lines of length 50 user units along

the axes of the new coordinate system -->

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" stroke="red" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="30" y="30" font-size="20" font-family="Verdana" >

ABC (translated coord system)

</text>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

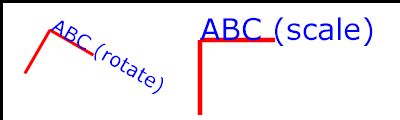

Example RotateScale

illustrates simple rotate and

scale transformations. The example defines two

new coordinate systems:

- one which is the result of a translation by 50 units in X

and 30 units in Y, followed by a rotation of 30 degrees

- another which is the result of a translation by 200 units

in X and 40 units in Y, followed by a scale transformation of

1.5.

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="400px" height="120px" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<desc>Example RotateScale - Rotate and scale transforms</desc>

<g fill="none" stroke="black" stroke-width="3" >

<!-- Draw the axes of the original coordinate system -->

<line x1="0" y1="1.5" x2="400" y2="1.5" />

<line x1="1.5" y1="0" x2="1.5" y2="120" />

</g>

<!-- Establish a new coordinate system whose origin is at (50,30)

in the initial coord. system and which is rotated by 30 degrees. -->

<g transform="translate(50,30)">

<g transform="rotate(30)">

<g fill="none" stroke="red" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="0" y="0" font-size="20" font-family="Verdana" fill="blue" >

ABC (rotate)

</text>

</g>

</g>

<!-- Establish a new coordinate system whose origin is at (200,40)

in the initial coord. system and which is scaled by 1.5. -->

<g transform="translate(200,40)">

<g transform="scale(1.5)">

<g fill="none" stroke="red" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="0" y="0" font-size="20" font-family="Verdana" fill="blue" >

ABC (scale)

</text>

</g>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

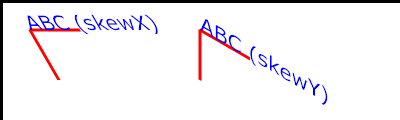

Example Skew defines two

coordinate systems which are skewed relative

to the origin coordinate system.

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="400px" height="120px" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<desc>Example Skew - Show effects of skewX and skewY</desc>

<g fill="none" stroke="black" stroke-width="3" >

<!-- Draw the axes of the original coordinate system -->

<line x1="0" y1="1.5" x2="400" y2="1.5" />

<line x1="1.5" y1="0" x2="1.5" y2="120" />

</g>

<!-- Establish a new coordinate system whose origin is at (30,30)

in the initial coord. system and which is skewed in X by 30 degrees. -->

<g transform="translate(30,30)">

<g transform="skewX(30)">

<g fill="none" stroke="red" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="0" y="0" font-size="20" font-family="Verdana" fill="blue" >

ABC (skewX)

</text>

</g>

</g>

<!-- Establish a new coordinate system whose origin is at (200,30)

in the initial coord. system and which is skewed in Y by 30 degrees. -->

<g transform="translate(200,30)">

<g transform="skewY(30)">

<g fill="none" stroke="red" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="0" y="0" font-size="20" font-family="Verdana" fill="blue" >

ABC (skewY)

</text>

</g>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

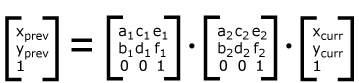

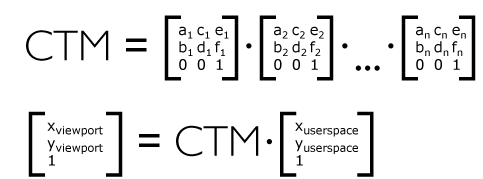

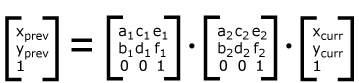

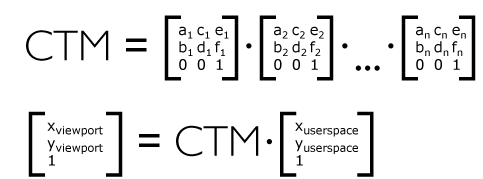

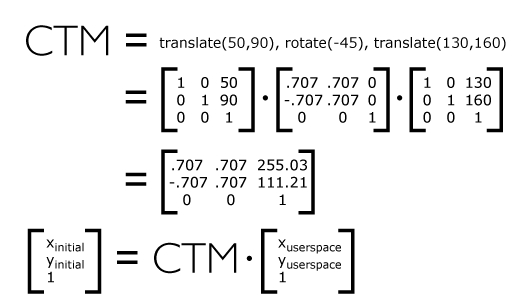

Transformations can be nested to any level. The effect of

nested transformations is to post-multiply (i.e., concatenate)

the subsequent transformation matrices onto previously defined

transformations:

For each given element, the accumulation of all

transformations that have been defined on the given element and

all of its ancestors up to and including the element that

established the current viewport (usually, the ‘svg’

element which is the most

immediate ancestor to the given element) is called the

current transformation matrix or

CTM. The CTM thus represents the

mapping of current user coordinates to viewport

coordinates:

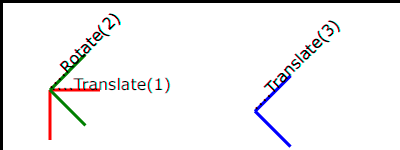

Example Nested illustrates

nested transformations.

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="400px" height="150px" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<desc>Example Nested - Nested transformations</desc>

<g fill="none" stroke="black" stroke-width="3" >

<!-- Draw the axes of the original coordinate system -->

<line x1="0" y1="1.5" x2="400" y2="1.5" />

<line x1="1.5" y1="0" x2="1.5" y2="150" />

</g>

<!-- First, a translate -->

<g transform="translate(50,90)">

<g fill="none" stroke="red" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="0" y="0" font-size="16" font-family="Verdana" >

....Translate(1)

</text>

<!-- Second, a rotate -->

<g transform="rotate(-45)">

<g fill="none" stroke="green" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="0" y="0" font-size="16" font-family="Verdana" >

....Rotate(2)

</text>

<!-- Third, another translate -->

<g transform="translate(130,160)">

<g fill="none" stroke="blue" stroke-width="3" >

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="50" y2="0" />

<line x1="0" y1="0" x2="0" y2="50" />

</g>

<text x="0" y="0" font-size="16" font-family="Verdana" >

....Translate(3)

</text>

</g>

</g>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

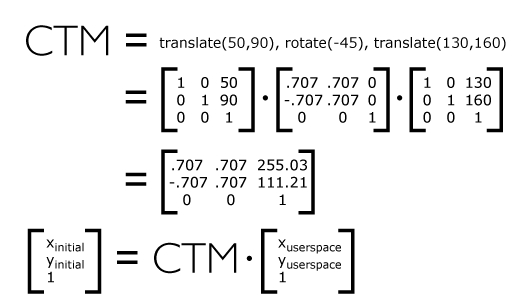

In the example above, the CTM within the third nested

transformation (i.e., the transform="translate(130,160)")

consists of the concatenation of the three transformations, as

follows:

The term <transform-list> used by this specification is equivalent to a list of <transform-functions>, the value of the ‘transform’

property.

See the CSS3 Transforms spec for the description of the ‘

transform’ property and the value of

<transform-functions> [

CSS3TRANSFORMS].

7.7. The ‘viewBox’ attribute

It is often desirable to specify that a given set of

graphics stretch to fit a particular container element. The

‘viewBox’ attribute provides this

capability.

All elements that establish a new viewport (see elements that

establish viewports), plus the

‘marker’,

‘pattern’ and

‘view’

elements have attribute

‘viewBox’. The value of the ‘viewBox’ attribute is a list of four

numbers <min-x>, <min-y>, <width> and <height>, separated by

whitespace and/or a comma, which specify a rectangle in user

space which should be mapped to the bounds of the viewport

established by the given element, taking into account attribute

‘preserveAspectRatio’. If specified,

an additional transformation is applied to all descendants of

the given element to achieve the specified effect.

A negative value for <width> or <height> is an error (see Error processing). A

value of zero disables rendering of the element.

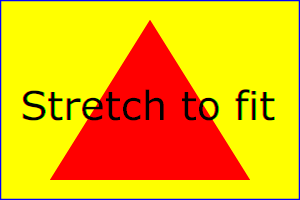

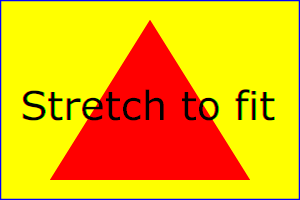

Example ViewBox illustrates

the use of the ‘viewBox’ attribute

on the outermost svg element to specify that

the SVG content should stretch to fit bounds of the

viewport.

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="300px" height="200px" version="1.1"

viewBox="0 0 1500 1000" preserveAspectRatio="none"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<desc>Example ViewBox - uses the viewBox

attribute to automatically create an initial user coordinate

system which causes the graphic to scale to fit into the

viewport no matter what size the viewport is.</desc>

<!-- This rectangle goes from (0,0) to (1500,1000) in user space.

Because of the viewBox attribute above,

the rectangle will end up filling the entire area

reserved for the SVG content. -->

<rect x="0" y="0" width="1500" height="1000"

fill="yellow" stroke="blue" stroke-width="12" />

<!-- A large, red triangle -->

<path fill="red" d="M 750,100 L 250,900 L 1250,900 z"/>

<!-- A text string that spans most of the viewport -->

<text x="100" y="600" font-size="200" font-family="Verdana" >

Stretch to fit

</text>

</svg>

Example ViewBox

Rendered into

viewport with

width=300px,

height=200px |

|

Rendered into

viewport with

width=150px,

height=200px |

|

|

|

View

this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

The effect of the ‘viewBox’

attribute is that the user agent automatically supplies the

appropriate transformation matrix to map the specified

rectangle in user space to the bounds of a designated region

(often, the viewport). To achieve the effect of the example on

the left, with viewport dimensions of 300 by 200 pixels, the

user agent needs to automatically insert a transformation which

scales both X and Y by 0.2. The effect is equivalent to having

a viewport of size 300px by 200px and the following

supplemental transformation in the document, as follows:

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="300px" height="200px" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g transform="scale(0.2)">

<!-- Rest of document goes here -->

</g>

</svg>

To achieve the effect of the example on the right, with

viewport dimensions of 150 by 200 pixels, the user agent needs

to automatically insert a transformation which scales X by 0.1

and Y by 0.2. The effect is equivalent to having a viewport of

size 150px by 200px and the following supplemental

transformation in the document, as follows:

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="150px" height="200px" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g transform="scale(0.1 0.2)">

<!-- Rest of document goes here -->

</g>

</svg>

(Note: in some cases the user agent will need to supply a

translate transformation in addition to a

scale transformation. For example, on an

outermost svg element, a

translate transformation will be needed if the

‘viewBox’ attributes specifies

values other than zero for <min-x> or <min-y>.)

Unlike the

‘transform’ property (see

effect of the ‘transform’ attribute on sibling attributes),

the automatic transformation that is created

due to a ‘viewBox’ does not affect

the ‘x’, ‘y’, ‘width’ and ‘height’ attributes (or in the case of

the ‘marker’ element, the

‘markerWidth’ and ‘markerHeight’ attributes) on the

element with the ‘viewBox’

attribute. Thus, in the example above which shows an

‘svg’ element which has attributes

‘width’,

‘height’ and ‘viewBox’,

the ‘width’ and ‘height’ attributes

represent values in the coordinate system that exists before the

‘viewBox’ transformation is applied. On

the other hand, like the ‘transform’ property, it does

establish a new coordinate system for all other attributes and

for descendant elements.

Link to the "effect of the 'transform' attribute on sibling attributes"

in the above paragraph needs to be update.

For the ‘viewBox’ attribute:

Animatable:

yes.

7.8. The ‘preserveAspectRatio’

attribute

In some cases, typically when using the

‘viewBox’ attribute, it is desirable that the graphics stretch to

fit non-uniformly to take up the

entire viewport. In other cases, it is desirable that uniform

scaling be used for the purposes of preserving the aspect ratio

of the graphics.

Attribute preserveAspectRatio="[defer] <align>

[<meetOrSlice>]", which is available for all

elements that establish a new viewport (see elements that

establish viewports), plus the

‘image’,

‘marker’,

‘pattern’ and

‘view’ elements,

indicates whether or not to force uniform scaling.

For elements that establish a new viewport (see elements that

establish viewports), plus the

‘marker’,

‘pattern’ and

‘view’ elements,

‘preserveAspectRatio’ only applies when

a value has been provided for ‘viewBox’

on the same element. For these elements, if attribute

‘viewBox’ is not provided, then

‘preserveAspectRatio’ is ignored.

For ‘image’ elements,

‘preserveAspectRatio’ indicates how

referenced images should be fitted with respect to the

reference rectangle and whether the aspect ratio of the

referenced image should be preserved with respect to the

current user coordinate system.

If the value of ‘preserveAspectRatio’ on an

‘image’ element starts with 'defer' then the value of the

‘preserveAspectRatio’ attribute on the

referenced content if present should be used. If the

referenced content lacks a value for

‘preserveAspectRatio’ then the

‘preserveAspectRatio’ attribute should

be processed as normal (ignoring 'defer').

For ‘preserveAspectRatio’ on all other

elements the 'defer' portion of the attribute is ignored.

The <align> parameter

indicates whether to force uniform scaling and, if so, the

alignment method to use in case the aspect ratio of the ‘viewBox’

doesn't match the aspect ratio of the viewport. The <align> parameter must be one

of the following strings:

- none - Do not force

uniform scaling. Scale the graphic content of the given

element non-uniformly if necessary such that the element's

bounding box exactly matches the viewport rectangle.

(Note: if <align> is

none, then the optional <meetOrSlice> value is

ignored.)

- xMinYMin - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the <min-x> of

the element's ‘viewBox’ with the smallest X

value of the viewport.

Align the <min-y> of

the element's ‘viewBox’ with the smallest Y

value of the viewport.

- xMidYMin - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the midpoint X value of the element's

‘viewBox’ with the midpoint X value of the viewport.

Align the <min-y> of

the element's ‘viewBox’ with the smallest Y

value of the viewport.

- xMaxYMin - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the <min-x>+<width> of the

element's ‘viewBox’ with the maximum X value

of the viewport.

Align the <min-y> of

the element's ‘viewBox’ with the smallest Y

value of the viewport.

- xMinYMid - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the <min-x> of

the element's ‘viewBox’ with the smallest X

value of the viewport.

Align the midpoint Y value of the element's ‘viewBox’

with the midpoint Y

value of the viewport.

- xMidYMid (the default) -

Force uniform scaling.

Align the midpoint X value of the element's ‘viewBox’

with the midpoint X value of the viewport.

Align the midpoint Y value of the element's ‘viewBox’

with the midpoint Y value of the viewport.

- xMaxYMid - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the <min-x>+<width> of the

element's ‘viewBox’

with the maximum X value of the viewport.

Align the midpoint Y value of the element's ‘viewBox’

with the midpoint Y

value of the viewport.

- xMinYMax - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the <min-x> of

the element's ‘viewBox’ with the smallest X

value of the viewport.

Align the <min-y>+<height> of the

element's ‘viewBox’ with the maximum Y value

of the viewport.

- xMidYMax - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the midpoint X value of the element's ‘viewBox’

with the midpoint X value of the viewport.

Align the <min-y>+<height> of the

element's ‘viewBox’ with the maximum Y value

of the viewport.

- xMaxYMax - Force uniform

scaling.

Align the <min-x>+<width> of the

element's ‘viewBox’ with the maximum X value

of the viewport.

Align the <min-y>+<height> of the

element's ‘viewBox’ with the maximum Y value

of the viewport.

The <meetOrSlice>

parameter is optional and, if provided, is separated from the

<align> value by one or

more spaces and then must be one of the following strings:

-

meet (the default) - Scale

the graphic such that:

- aspect ratio is preserved

- the entire ‘viewBox’ is visible within

the viewport

- the ‘viewBox’ is scaled up as much

as possible, while still meeting the other criteria

In this case, if the aspect ratio of the graphic does not

match the viewport, some of the viewport will extend beyond

the bounds of the ‘viewBox’ (i.e., the area into

which the ‘viewBox’ will draw will be

smaller than the viewport).

-

slice - Scale the graphic

such that:

- aspect ratio is preserved

- the entire viewport is covered by the ‘viewBox’

- the ‘viewBox’ is scaled down as

much as possible, while still meeting the other

criteria

In this case, if the aspect ratio of the ‘viewBox’ does not match the

viewport, some of the ‘viewBox’ will extend beyond the

bounds of the viewport (i.e., the area into which the ‘viewBox’ will draw is larger

than the viewport).

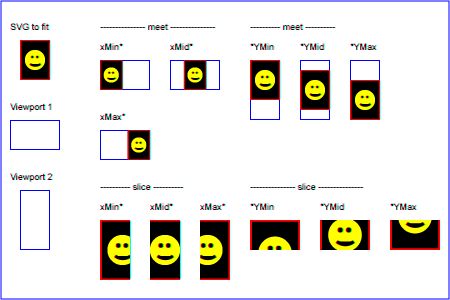

Example PreserveAspectRatio

illustrates the various options on ‘preserveAspectRatio’. To save space,

XML entities have been defined for the three repeated graphic

objects, the rectangle with the smile inside and the outlines

of the two rectangles which have the same dimensions as the

target viewports. The example creates several new viewports by

including ‘svg’ sub-elements embedded

inside the outermost svg element (see Establishing a new

viewport).

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE svg [

<!ENTITY Smile "

<rect x='.5' y='.5' width='29' height='39' fill='black' stroke='red'/>

<g transform='translate(0, 5)'>

<circle cx='15' cy='15' r='10' fill='yellow'/>

<circle cx='12' cy='12' r='1.5' fill='black'/>

<circle cx='17' cy='12' r='1.5' fill='black'/>

<path d='M 10 19 A 8 8 0 0 0 20 19' stroke='black' stroke-width='2'/>

</g>

">

<!ENTITY Viewport1 "<rect x='.5' y='.5' width='49' height='29'

fill='none' stroke='blue'/>">

<!ENTITY Viewport2 "<rect x='.5' y='.5' width='29' height='59'

fill='none' stroke='blue'/>">

]>

<svg width="450px" height="300px" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<desc>Example PreserveAspectRatio - illustrates preserveAspectRatio attribute</desc>

<rect x="1" y="1" width="448" height="298"

fill="none" stroke="blue"/>

<g font-size="9">

<text x="10" y="30">SVG to fit</text>

<g transform="translate(20,40)">&Smile;</g>

<text x="10" y="110">Viewport 1</text>

<g transform="translate(10,120)">&Viewport1;</g>

<text x="10" y="180">Viewport 2</text>

<g transform="translate(20,190)">&Viewport2;</g>

<g id="meet-group-1" transform="translate(100, 60)">

<text x="0" y="-30">--------------- meet ---------------</text>

<g><text y="-10">xMin*</text>&Viewport1;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMinYMin meet" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="50" height="30">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(70,0)"><text y="-10">xMid*</text>&Viewport1;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMidYMid meet" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="50" height="30">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(0,70)"><text y="-10">xMax*</text>&Viewport1;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMaxYMax meet" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="50" height="30">&Smile;</svg></g>

</g>

<g id="meet-group-2" transform="translate(250, 60)">

<text x="0" y="-30">---------- meet ----------</text>

<g><text y="-10">*YMin</text>&Viewport2;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMinYMin meet" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="30" height="60">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(50, 0)"><text y="-10">*YMid</text>&Viewport2;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMidYMid meet" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="30" height="60">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(100, 0)"><text y="-10">*YMax</text>&Viewport2;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMaxYMax meet" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="30" height="60">&Smile;</svg></g>

</g>

<g id="slice-group-1" transform="translate(100, 220)">

<text x="0" y="-30">---------- slice ----------</text>

<g><text y="-10">xMin*</text>&Viewport2;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMinYMin slice" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="30" height="60">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(50,0)"><text y="-10">xMid*</text>&Viewport2;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMidYMid slice" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="30" height="60">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(100,0)"><text y="-10">xMax*</text>&Viewport2;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMaxYMax slice" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="30" height="60">&Smile;</svg></g>

</g>

<g id="slice-group-2" transform="translate(250, 220)">

<text x="0" y="-30">--------------- slice ---------------</text>

<g><text y="-10">*YMin</text>&Viewport1;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMinYMin slice" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="50" height="30">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(70,0)"><text y="-10">*YMid</text>&Viewport1;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMidYMid slice" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="50" height="30">&Smile;</svg></g>

<g transform="translate(140,0)"><text y="-10">*YMax</text>&Viewport1;

<svg preserveAspectRatio="xMaxYMax slice" viewBox="0 0 30 40"

width="50" height="30">&Smile;</svg></g>

</g>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

This example should stop using DTD entities and

use ‘use’ instead.

For the ‘preserveAspectRatio’

attribute:

Animatable: yes.

7.9. Establishing a new viewport

At any point in an SVG drawing, you can establish a new

viewport into which all contained graphics is drawn by

including an ‘svg’ element

inside SVG content. By establishing a new viewport, you also

implicitly establish a new viewport coordinate system, a new

user coordinate system, and, potentially, a new clipping path

(see the definition of the ‘overflow’ property).

Additionally, there is a new meaning for percentage units

defined to be relative to the current viewport since a new

viewport has been established (see Units).

The bounds of the new viewport are defined by the ‘x’, ‘y’,

‘width’ and ‘height’ attributes on the element

establishing the new viewport, such as an ‘svg’ element. Both the new

viewport coordinate system and the new user coordinate system

have their origins at (‘x’, ‘y’), where ‘x’ and ‘y’

represent the value of the corresponding attributes on the

element establishing the viewport. The orientation of the new

viewport coordinate system and the new user coordinate system

correspond to the orientation of the current user coordinate

system for the element establishing the viewport. A single unit

in the new viewport coordinate system and the new user

coordinate system are the same size as a single unit in the

current user coordinate system for the element establishing the

viewport.

Here is an example:

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="4in" height="3in" version="1.1"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<desc>This SVG drawing embeds another one,

thus establishing a new viewport

</desc>

<!-- The following statement establishing a new viewport

and renders SVG drawing B into that viewport -->

<svg x="25%" y="25%" width="50%" height="50%">

<!-- drawing B goes here -->

</svg>

</svg>

For an extensive example of creating new viewports, see Example

PreserveAspectRatio.

The following elements establish new viewports:

- The ‘svg’ element

- A ‘symbol’ element define new

viewports whenever they are instanced by a ‘use’ element.

- An ‘image’ element that

references an SVG file will result in the establishment of a

temporary new viewport since the referenced resource by

definition will have an ‘svg’ element.

- A ‘foreignObject’ element

creates a new viewport for rendering the content that is

within the element.

Whether a new viewport also establishes a new additional

clipping path is determined by the value of the ‘overflow’ property on the element

that establishes the new viewport. If a clipping path is

created to correspond to the new viewport, the clipping path's

geometry is determined by the value of the ‘clip’ property. Also, see Clip to

viewport vs. clip to ‘viewBox’.

7.10. Units

All coordinates and lengths in SVG can be specified with or

without a unit identifier.

This is misleading – path data for example takes values that look

like coordinates and lengths yet does not allow units.

When a coordinate or length value is a number without a unit

identifier (e.g., "25"), then the given coordinate or length is

assumed to be in user units (i.e., a value in the current user

coordinate system). For example:

<text font-size="50">Text size is 50 user units</text>

Alternatively, a coordinate or length value can be expressed

as a number followed by a unit identifier (e.g., "25cm" or

"15em").

(Note that CSS defined properties used in a CSS style sheet

or the ‘style’ attribute require units for

non-zero lengths, see SVG's styling

properties.)

The list of unit identifiers in SVG matches the list

of unit identifiers in CSS: em, ex, px, pt, pc, cm, mm and in.

The <length> type can also have

a percentage unit identifier. The following describes how the various unit

identifiers are processed:

- As in CSS, the em and ex unit

identifiers are relative to the current font's

font-size and x-height, respectively.

-

One px unit is defined to be equal to one user

unit. Thus, a length of "5px" is the same as a length of

"5".

Note that at initialization, a user unit in the the initial

coordinate system is equivalenced to the parent

environment's notion of a px unit. Thus, in the the initial

coordinate system, because the user coordinate system

aligns exactly with the parent's coordinate system, and

because often the parent's coordinate system aligns with

the device pixel grid, "5px" might actually map to 5

devices pixels. However, if there are any coordinate system

transformation due to the use of ‘transform’ or

‘viewBox’ attributes, because

"5px" maps to 5 user units and because the coordinate

system transformations have resulted in a revised user

coordinate system, "5px" likely will not map to 5 device

pixels. As a result, in most circumstances, "px" units will

not map to the device pixel grid.

-

The other absolute unit identifiers from CSS (i.e., pt,

pc, cm, mm, in) are all defined as an appropriate multiple

of one px unit (which, according to the previous

item, is defined to be equal to one user unit), based on

what the SVG user agent determines is the size of a

px unit (possibly passed from the parent processor

or environment at initialization time). For example,

suppose that the user agent can determine from its

environment that "1px" corresponds to "0.2822222mm" (i.e.,

90dpi). Then, for all processing of SVG content:

- "1pt" equals "1.25px" (and therefore 1.25 user units)

- "1pc" equals "15px" (and therefore 15 user units)

- "1mm" would be "3.543307px" (3.543307 user units)

- "1cm" equals "35.43307px" (and therefore 35.43307 user units)

- "1in" equals "90px" (and therefore 90 user units)

Note that use of px units or any other absolute

unit identifiers can cause inconsistent visual results on

different viewing environments since the size of "1px" may map

to a different number of user units on different systems; thus,

absolute units identifiers are only recommended for the

‘width’ and the ‘height’ on

outermost svg elements and situations

where the content contains no transformations and it is

desirable to specify values relative to the device pixel grid

or to a particular real world unit size.

For percentage values that are defined to be relative to the

size of viewport:

- For any x-coordinate value or width value expressed as a

percentage of the viewport, the value to use is the specified

percentage of the actual-width in user units for the

nearest containing viewport, where actual-width is

the width dimension of the viewport element within the user

coordinate system for the viewport element.

- For any y-coordinate value or height value expressed as a

percentage of the viewport, the value to use is the specified

percentage of the actual-height in user units for

the nearest containing viewport, where actual-height

is the height dimension of the viewport element within the

user coordinate system for the viewport element.

- For any other length value expressed as a percentage of

the viewport, the percentage is calculated as the specified

percentage of

sqrt((actual-width)**2 +

(actual-height)**2)/sqrt(2).

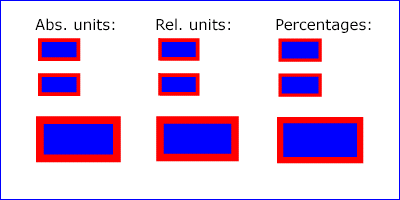

Example Units below

illustrates some of the processing rules for different types of

units.

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="no"?>

<svg width="400px" height="200px" viewBox="0 0 4000 2000"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.1">

<title>Example Units</title>

<desc>Illustrates various units options</desc>

<!-- Frame the picture -->

<rect x="5" y="5" width="3990" height="1990"

fill="none" stroke="blue" stroke-width="10"/>

<g fill="blue" stroke="red" font-family="Verdana" font-size="150">

<!-- Absolute unit specifiers -->

<g transform="translate(400,0)">

<text x="-50" y="300" fill="black" stroke="none">Abs. units:</text>

<rect x="0" y="400" width="4in" height="2in" stroke-width=".4in"/>

<rect x="0" y="750" width="384" height="192" stroke-width="38.4"/>

<g transform="scale(2)">

<rect x="0" y="600" width="4in" height="2in" stroke-width=".4in"/>

</g>

</g>

<!-- Relative unit specifiers -->

<g transform="translate(1600,0)">

<text x="-50" y="300" fill="black" stroke="none">Rel. units:</text>

<rect x="0" y="400" width="2.5em" height="1.25em" stroke-width=".25em"/>

<rect x="0" y="750" width="375" height="187.5" stroke-width="37.5"/>

<g transform="scale(2)">

<rect x="0" y="600" width="2.5em" height="1.25em" stroke-width=".25em"/>

</g>

</g>

<!-- Percentages -->

<g transform="translate(2800,0)">

<text x="-50" y="300" fill="black" stroke="none">Percentages:</text>

<rect x="0" y="400" width="10%" height="10%" stroke-width="1%"/>

<rect x="0" y="750" width="400" height="200" stroke-width="31.62"/>

<g transform="scale(2)">

<rect x="0" y="600" width="10%" height="10%" stroke-width="1%"/>

</g>

</g>

</g>

</svg>View this example as SVG (SVG-enabled browsers only)

The three rectangles on the left demonstrate the use of one

of the absolute unit identifiers, the "in" unit (inch). The

reference image above was generated on a 96dpi system (i.e., 1

inch = 96 pixels). Therefore, the topmost rectangle, which is

specified in inches, is exactly the same size as the middle

rectangle, which is specified in user units such that there are

96 user units for each corresponding inch in the topmost

rectangle. (Note: on systems with different screen resolutions,

the top and middle rectangles will likely be rendered at

different sizes.) The bottom rectangle of the group illustrates

what happens when values specified in inches are scaled.

The three rectangles in the middle demonstrate the use of

one of the relative unit identifiers, the "em" unit. Because

the ‘font-size’ property has been set

to 150 on the outermost ‘g’ element, each "em" unit is

equal to 150 user units. The topmost rectangle, which is

specified in "em" units, is exactly the same size as the middle

rectangle, which is specified in user units such that there are

150 user units for each corresponding "em" unit in the topmost

rectangle. The bottom rectangle of the group illustrates what

happens when values specified in "em" units are scaled.

The three rectangles on the right demonstrate the use of

percentages. Note that the width and height of the viewport in

the user coordinate system for the viewport element (in this

case, the outermost svg element) are 4000 and

2000, respectively, because processing the ‘viewBox’ attribute results in a

transformed user coordinate system. The topmost rectangle,

which is specified in percentage units, is exactly the same

size as the middle rectangle, which is specified in equivalent

user units. In particular, note that the ‘stroke-width’ property in the

middle rectangle is set to 1% of the

sqrt((actual-width)**2 +

(actual-height)**2) / sqrt(2), which in this

case is .01*sqrt(4000*4000+2000*2000)/sqrt(2), or 31.62. The

bottom rectangle of the group illustrates what happens when

values specified in percentage units are scaled.

7.11. Object bounding box units

The following elements offer the option of expressing

coordinate values and lengths as fractions (and, in some cases,

percentages) of the bounding box,

by setting a specified attribute to 'objectBoundingBox'

on the given element:

| Element |

Attribute |

Effect |

| ‘linearGradient’ |

‘gradientUnits’ |

Indicates that the attributes which specify the

gradient vector (‘x1’, ‘y1’, ‘x2’, ‘y2’) represent fractions or

percentages of the bounding box of the element to which the

gradient is applied. |

| ‘radialGradient’ |

‘gradientUnits’ |

Indicates that the attributes which specify the center

(‘cx’, ‘cy’), the radius (‘r’) and focus

(‘fx’, ‘fy’) represent fractions or

percentages of the bounding box of the element to which the

gradient is applied. |

| ‘pattern’ |

‘patternUnits’ |

Indicates that the attributes which define how to tile the pattern

(‘x’, ‘y’, ‘width’, ‘height’) are

established using the bounding box of the element to which the pattern

is applied. |

| ‘pattern’ |

‘patternContentUnits’ |

Indicates that the user coordinate system for the

contents of the pattern is established using the bounding

box of the element to which the pattern is applied. |

| ‘clipPath’ |

‘clipPathUnits’ |

Indicates that the user coordinate system for the contents of the

‘clipPath’ element is established using the bounding box of the

element to which the clipping path is applied. |

| ‘mask’ |

‘maskUnits’ |

Indicates that the attributes which define the masking region

(‘x’, ‘y’, ‘width’, ‘height’) is

established using the bounding box of the element to which the mask

is applied. |

| ‘mask’ |

‘maskContentUnits’ |

Indicates that the user coordinate system for the contents of

the ‘mask’ element are established using the bounding box of

the element to which the mask is applied. |

| ‘filter’ |

‘filterUnits’ |

Indicates that the attributes which define the

filter effects region

(‘x’, ‘y’, ‘width’, ‘height’) represent

fractions or percentages of the bounding box of the element to which

the filter is applied. |

| ‘filter’ |

‘primitiveUnits’ |

Indicates that the various length values within the filter

primitives represent fractions or percentages of the bounding box of

the element to which the filter is applied. |

In the discussion that follows, the term applicable element

is the element to which the given effect applies. For gradients and

patterns, the applicable element is the graphics element

which has its ‘fill’ or ‘stroke’ property referencing the

given gradient or pattern. (See Inheritance

of Painting Properties. For special rules concerning text elements, see the discussion of object

bounding box units and text elements.) For clipping paths,

masks and filters, the applicable element can be either a

container element or a graphics element.

When keyword objectBoundingBox is used, then the

effect is as if a supplemental transformation matrix were

inserted into the list of nested transformation matrices to

create a new user coordinate system.

First, the (minx,miny) and

(maxx,maxy) coordinates are

determined for the applicable element and all of its

descendants. The values minx,

miny, maxx and

maxy are determined by computing the maximum

extent of the shape of the element in X and Y with respect to

the user coordinate system for the applicable element. The

bounding box is the tightest fitting rectangle aligned with the

axes of the applicable element's user coordinate system that

entirely encloses the applicable element and its descendants.

The bounding box is computed exclusive of any values for

clipping, masking, filter effects, opacity and stroke-width.

For curved shapes, the bounding box encloses all portions of

the shape, not just end points. For ‘text’ elements, for the

purposes of the bounding box calculation, each glyph is treated

as a separate graphics element. The calculations assume that

all glyphs occupy the full glyph cell. For example, for

horizontal text, the calculations assume that each glyph

extends vertically to the full ascent and descent values for

the font.

Then, coordinate (0,0) in the new user coordinate system is

mapped to the (minx,miny) corner of the tight bounding box

within the user coordinate system of the applicable element and

coordinate (1,1) in the new user coordinate system is mapped to

the (maxx,maxy) corner of the tight bounding box of the

applicable element. In most situations, the following

transformation matrix produces the correct effect:

[ (maxx-minx) 0 0 (maxy-miny) minx miny ]

When percentages are used with attributes that define the

gradient vector, the pattern tile, the filter region or the

masking region, a percentage represents the same value as the

corresponding decimal value (e.g., 50% means the same as 0.5).

If percentages are used within the content of a ‘pattern’,

‘clipPath’, ‘mask’ or ‘filter’ element, these values

are treated according to the processing rules for percentages

as defined in Units.

Any numeric value can be specified for values expressed as a

fraction or percentage of object bounding box units. In

particular, fractions less are zero or greater than one and

percentages less than 0% or greater than 100% can be

specified.

Keyword objectBoundingBox

should not be used when the geometry of the applicable element

has no width or no height, such as the case of a horizontal or

vertical line, even when the line has actual thickness when

viewed due to having a non-zero stroke width since stroke width

is ignored for bounding box calculations. When the geometry of

the applicable element has no width or height and objectBoundingBox is specified, then

the given effect (e.g., a gradient or a filter) will be

ignored.

7.12. Intrinsic sizing properties of the viewport of SVG content

SVG needs to specify how to calculate some intrinsic sizing properties to

enable inclusion within other languages. The intrinsic width and height

of the viewport of SVG content must be determined from the ‘width’

and ‘height’ attributes. If either of these are not specified, a

value of '100%' must be assumed.

Note: the ‘width’ and ‘height’

attributes are not the same as the CSS width and height properties.

Specifically, percentage values do not provide an intrinsic width or height,

and do not indicate a percentage of the containing block. Rather, once the

viewport is established, they indicate the portion of the viewport that is

actually covered by image data.

The intrinsic aspect ratio of the viewport of SVG content is necessary

for example, when including SVG from an ‘object’ element in HTML styled with

CSS. It is possible (indeed, common) for an SVG graphic to have an intrinsic aspect ratio but not to have an intrinsic width or height.

The intrinsic aspect ratio must be calculated based upon the

following rules:

- The aspect ratio is calculated by dividing a width by a height.

- If the ‘width’ and ‘height’

of the rootmost ‘svg’ element are both specified with

unit identifiers (in, mm, cm, pt, pc, px, em, ex) or in user units, then the aspect ratio is

calculated from the ‘width’ and ‘height’ attributes after resolving both values to user units.

- If either/both of the ‘width’ and ‘height’ of the rootmost ‘svg’ element are in

percentage units (or omitted), the aspect ratio is calculated from the width and

height values of the ‘viewBox’ specified for the current SVG document fragment.

If the ‘viewBox’ is not correctly specified, or set to 'none',

the intrinsic aspect ratio cannot be calculated and is considered unspecified.

Examples:

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.2" baseProfile="tiny"

width="10cm" height="5cm">

...

</svg>

In this example the intrinsic aspect ratio of the viewport is 2:1. The

intrinsic width is 10cm and the intrinsic height is 5cm.

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.2" baseProfile="tiny"

width="100%" height="50%" viewBox="0 0 200 200">

...

</svg>

In this example the intrinsic aspect ratio of the rootmost viewport is

1:1. An aspect ratio calculation in this case allows embedding in an

object within a containing block that is only constrained in one direction.

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.2" baseProfile="tiny"

width="10cm" viewBox="0 0 200 200">

...

</svg>

In this case the intrinsic aspect ratio is 1:1.

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.2" baseProfile="tiny"

width="75%" height="10cm" viewBox="0 0 200 200">

...

</svg>

In this example, the intrinsic aspect ratio is 1:1.

7.13. Geographic coordinate systems

In order to allow interoperability between SVG content generators

and user agents dealing with maps encoded in SVG, the use of a common

metadata definition for describing the coordinate system used to

generate SVG documents is encouraged.

Such metadata must be added under the ‘metadata’ element of

the topmost ‘svg’ element describing the map, consisting of an

RDF description of the Coordinate Reference System definition used to

generate the SVG map [RDF-PRIMER]. Note that

the presence of this metadata does not affect the rendering of the SVG

in any way; it merely provides added semantic value for applications

that make use of combined maps.

The definition must be conformant to the XML grammar described in

GML 3.2.1,

an OpenGIS Standard for encoding common CRS data types in XML

[GML]. In order to correctly map

the 2-dimensional data used by SVG, the CRS must be of subtype

ProjectedCRS or Geographic2dCRS. The

first axis of the described CRS maps the SVG x-axis and the

second axis maps the SVG y-axis.

The main purpose of such metadata is to indicate to the user agent

that two or more SVG documents can be overlayed or merged into a single

document. Obviously, if two maps reference the same Coordinate Reference

System definition and have the same SVG ‘transform’ property

value then they can be overlayed without reprojecting the data. If

the maps reference different Coordinate Reference Systems and/or have

different SVG ‘transform’ property values, then a specialized

cartographic user agent may choose to transform the coordinate data to

overlay the data. However, typical SVG user agents are not required

to perform these types of transformations, or even recognize the

metadata. It is described in this specification so that the connection

between geographic coordinate systems and the SVG coordinate system is

clear.

Attribute definition:

- svg:transform = "<transform>" | "none"

-

- <transform>

-

Specifies the affine transformation that has been

applied to the map data. The syntax is identical to

that described in The ‘transform’ property

section.

- none

-

Specifies that no supplemental affine transformation has been

applied to the map data. Using this value has the same meaning as

specifying the identity matrix, which in turn is just the same as

not specifying the

‘svg:transform’

the attribute at all.

Animatable: no.

This attribute describes an optional additional affine

transformation that may have been applied during this

mapping. This attribute may be added to the OpenGIS

‘CoordinateReferenceSystem’ element. Note

that, unlike the ‘transform’ property, it does not indicate that

a transformation is to be applied to the data within the file.

Instead, it simply describes the transformation that was already

applied to the data when being encoded in SVG.

There are three typical uses for the

‘svg:transform’

global attribute. These are described below and used in the examples.

- Most ProjectedCRS have the north direction represented by

positive values of the second axis and conversely SVG has a

y-down coordinate system. That's why, in order to follow the

usual way to represent a map with the north at its top, it is

recommended for that kind of ProjectedCRS to use the

‘svg:transform’

global attribute with a 'scale(1, -1)' value as in the

third example below.

- Most Geographic2dCRS have the latitude as their first

axis rather than the longitude, which means that the

south-north axis would be represented by the x-axis in SVG

instead of the usual y-axis. That's why, in order to follow

the usual way to represent a map with the north at its top,

it is recommended for that kind of Geographic2dCRS to use the

‘svg:transform’

global attribute with a 'rotate(-90)' value as in the

first example (while also adding the 'scale(1, -1)' as for

ProjectedCRS).

- In addition, when converting for profiles which place

restrictions on precision of real number values, it may be

useful to add an additional scaling factor to retain good

precision for a specific area. When generating an SVG

document from WGS84 geographic coordinates (EPGS 4326), we

recommend the use of an additional 100 times scaling factor

corresponding to an ‘svg:transform’

global attribute with a 'rotate(-90) scale(100)'

value (shown in the second example).

Different scaling values may be required depending on the

particular CRS.

Below is a simple example of the coordinate metadata, which

describes the coordinate system used by the document via a

URI.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.1"

width="100" height="100" viewBox="0 0 1000 1000">

<desc>An example that references coordinate data.</desc>

<metadata>

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:crs="http://www.ogc.org/crs"

xmlns:svg="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="">

<!-- The Coordinate Reference System is described

through a URI. -->

<crs:CoordinateReferenceSystem

svg:transform="rotate(-90)"

rdf:resource="http://www.example.org/srs/epsg.xml#4326"/>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>

</metadata>

<!-- The actual map content -->

</svg>The second example uses a well-known identifier to describe

the coordinate system. Note that the coordinates used in the

document have had the supplied transform applied.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.1"

width="100" height="100" viewBox="0 0 1000 1000">

<desc>Example using a well known coordinate system.</desc>

<metadata>

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:crs="http://www.ogc.org/crs"

xmlns:svg="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="">

<!-- In case of a well-known Coordinate Reference System

an 'Identifier' is enough to describe the CRS -->

<crs:CoordinateReferenceSystem svg:transform="rotate(-90) scale(100, 100)">

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>4326</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

</crs:CoordinateReferenceSystem>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>

</metadata>

<!-- The actual map content -->

</svg>The third example defines the coordinate system completely

within the SVG document.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" version="1.1"

width="100" height="100" viewBox="0 0 1000 1000">

<desc>Coordinate metadata defined within the SVG document</desc>

<metadata>

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:crs="http://www.ogc.org/crs"

xmlns:svg="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="">

<!-- For other CRS it should be entirely defined -->

<crs:CoordinateReferenceSystem svg:transform="scale(1,-1)">

<crs:NameSet>

<crs:name>Mercator projection of WGS84</crs:name>

</crs:NameSet>

<crs:ProjectedCRS>

<!-- The actual definition of the CRS -->

<crs:CartesianCoordinateSystem>

<crs:dimension>2</crs:dimension>

<crs:CoordinateAxis>

<crs:axisDirection>north</crs:axisDirection>

<crs:AngularUnit>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>9108</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

</crs:AngularUnit>

</crs:CoordinateAxis>

<crs:CoordinateAxis>

<crs:axisDirection>east</crs:axisDirection>

<crs:AngularUnit>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>9108</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

</crs:AngularUnit>

</crs:CoordinateAxis>

</crs:CartesianCoordinateSystem>

<crs:CoordinateReferenceSystem>

<!-- the reference system of that projected system is

WGS84 which is EPSG 4326 in EPSG codeSpace -->

<crs:NameSet>

<crs:name>WGS 84</crs:name>

</crs:NameSet>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>4326</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

</crs:CoordinateReferenceSystem>

<crs:CoordinateTransformationDefinition>

<crs:sourceDimensions>2</crs:sourceDimensions>

<crs:targetDimensions>2</crs:targetDimensions>

<crs:ParameterizedTransformation>

<crs:TransformationMethod>

<!-- the projection is a Mercator projection which is

EPSG 9805 in EPSG codeSpace -->

<crs:NameSet>

<crs:name>Mercator</crs:name>

</crs:NameSet>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>9805</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

<crs:description>Mercator (2SP)</crs:description>

</crs:TransformationMethod>

<crs:Parameter>

<crs:NameSet>

<crs:name>Latitude of 1st standart parallel</crs:name>

</crs:NameSet>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>8823</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

<crs:value>0</crs:value>

</crs:Parameter>

<crs:Parameter>

<crs:NameSet>

<crs:name>Longitude of natural origin</crs:name>

</crs:NameSet>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>8802</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

<crs:value>0</crs:value>

</crs:Parameter>

<crs:Parameter>

<crs:NameSet>

<crs:name>False Easting</crs:name>

</crs:NameSet>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>8806</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

<crs:value>0</crs:value>

</crs:Parameter>

<crs:Parameter>

<crs:NameSet>

<crs:name>False Northing</crs:name>

</crs:NameSet>

<crs:Identifier>

<crs:code>8807</crs:code>

<crs:codeSpace>EPSG</crs:codeSpace>

<crs:edition>5.2</crs:edition>

</crs:Identifier>

<crs:value>0</crs:value>

</crs:Parameter>

</crs:ParameterizedTransformation>

</crs:CoordinateTransformationDefinition>

</crs:ProjectedCRS>

</crs:CoordinateReferenceSystem>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>

</metadata>

<!-- the actual map content -->

</svg>7.15. DOM interfaces

7.15.1. Interface SVGPoint

Many of the SVG DOM interfaces refer to objects of class

SVGPoint. An SVGPoint is an (x, y) coordinate pair. When

used in matrix operations, an SVGPoint is treated as a vector of

the form:

[x]

[y]

[1]

If an SVGPoint object is designated as read only,

then attempting to assign to one of its attributes will result in

an exception being thrown.

interface SVGPoint {

attribute float x;

attribute float y;

SVGPoint matrixTransform(SVGMatrix matrix);

};

-

- x (float)

-

The x coordinate.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised if the SVGPoint object is read only.

- y (float)

-

The y coordinate.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised if the SVGPoint object is read only.

-

- SVGPoint matrixTransform(SVGMatrix matrix)

-

Applies a 2x3 matrix transformation on this SVGPoint object and

returns a new, transformed SVGPoint object:

newpoint = matrix * thispoint

-

-

The matrix which is to be applied to this

SVGPoint object.

-

7.15.2. Interface SVGPointList

This interface defines a list of SVGPoint objects.

SVGPointList has the same attributes and methods as other

SVGxxxList interfaces. Implementers may consider using a single base class

to implement the various SVGxxxList interfaces.

interface SVGPointList {

readonly attribute unsigned long numberOfItems;

void clear();

SVGPoint initialize(SVGPoint newItem);

SVGPoint getItem(unsigned long index):

SVGPoint insertItemBefore(SVGPoint newItem, unsigned long index);

SVGPoint replaceItem(SVGPoint newItem, unsigned long index);

SVGPoint removeItem(unsigned long index);

SVGPoint appendItem(SVGPoint newItem);

};

-

- numberOfItems (readonly unsigned long)

-

The number of items in the list.

-

- void clear()

-

Clears all existing current items from the list, with the result being

an empty list.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised when the list

cannot be modified.

- SVGPoint initialize(SVGPoint newItem)

-

Clears all existing current items from the list and re-initializes the

list to hold the single item specified by the parameter. If the inserted

item is already in a list, it is removed from its previous list before

it is inserted into this list. The inserted item is the item itself and

not a copy.

-

-

The item which should become the only member of the list.

-

The item being inserted into the list.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised when the list

cannot be modified.

- SVGPoint getItem(unsigned long index)

-

Returns the specified item from the list. The returned item is the

item itself and not a copy. Any changes made to the item are

immediately reflected in the list.

-

-

unsigned long index

The index of the item from the list which is to be

returned. The first item is number 0.

-

The selected item.

-

- DOMException, code INDEX_SIZE_ERR

- Raised if the index number is

greater than or equal to numberOfItems.

- SVGPoint insertItemBefore(SVGPoint newItem, unsigned long index)

-

Inserts a new item into the list at the specified position. The first

item is number 0. If newItem is already in a list, it is

removed from its previous list before it is inserted into this list.

The inserted item is the item itself and not a copy. If the item is

already in this list, note that the index of the item to insert

before is before the removal of the item.

-

-

The item which is to be inserted into the list.

-

unsigned long index

The index of the item before which the new item is to be

inserted. The first item is number 0. If the index is equal to 0,

then the new item is inserted at the front of the list. If the index

is greater than or equal to

numberOfItems, then the new item is

appended to the end of the list.

-

The inserted item.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised when the list

cannot be modified.

- SVGPoint replaceItem(SVGPoint newItem, unsigned long index)

-

Replaces an existing item in the list with a new item. If

newItem is already in a list, it is removed from its

previous list before it is inserted into this list. The inserted item

is the item itself and not a copy. If the item is already in this

list, note that the index of the item to replace is before

the removal of the item.

-

-

The item which is to be inserted into the list.

-

unsigned long index

The index of the item which is to be replaced. The first

item is number 0.

-

The inserted item.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised when the list

cannot be modified.

- DOMException, code INDEX_SIZE_ERR

- Raised if the index number is

greater than or equal to numberOfItems.

- SVGPoint removeItem(unsigned long index)

-

Removes an existing item from the list.

-

-

unsigned long index

The index of the item which is to be removed. The first

item is number 0.

-

The removed item.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised when the list

cannot be modified.

- DOMException, code INDEX_SIZE_ERR

- Raised if the index number is

greater than or equal to numberOfItems.

- SVGPoint appendItem(SVGPoint newItem)

-

Inserts a new item at the end of the list. If newItem is

already in a list, it is removed from its previous list before it is

inserted into this list. The inserted item is the item itself and

not a copy.

-

-

The item which is to be inserted. The first item is

number 0.

-

The inserted item.

-

- DOMException, code NO_MODIFICATION_ALLOWED_ERR

- Raised when the list

cannot be modified.

7.15.3. Interface SVGMatrix

Many of SVG's graphics operations utilize 2x3 matrices of the form:

[a c e]

[b d f]

which, when expanded into a 3x3 matrix for the purposes of matrix

arithmetic, become:

[a c e]

[b d f]

[0 0 1]

interface SVGMatrix {

attribute float a;

attribute float b;

attribute float c;

attribute float d;

attribute float e;

attribute float f;

SVGMatrix multiply(SVGMatrix secondMatrix);

SVGMatrix inverse();

SVGMatrix translate(float x, float y);

SVGMatrix scale(float scaleFactor);

SVGMatrix scaleNonUniform(float scaleFactorX, float scaleFactorY);

SVGMatrix rotate(float angle);

SVGMatrix rotateFromVector(float x, float y);

SVGMatrix flipX();

SVGMatrix flipY();

SVGMatrix skewX(float angle);

SVGMatrix skewY(float angle);

};

-

- a (float)

-

The a component of the matrix.

- b (float)

-

The b component of the matrix.

- c (float)

-

The c component of the matrix.

- d (float)

-

The d component of the matrix.

- e (float)

-

The e component of the matrix.

- f (float)

-

The f component of the matrix.

-

- SVGMatrix multiply(SVGMatrix secondMatrix)

-

Performs matrix multiplication. This matrix is post-multiplied by

another matrix, returning the resulting new matrix.

-

-

The matrix which is post-multiplied to this matrix.

-

The resulting matrix.

- SVGMatrix inverse()

-

Returns the inverse matrix.

-

The inverse matrix.

-

- InvalidStateError

- Raised if this matrix is

not invertible.

- SVGMatrix translate(float x, float y)

-

Post-multiplies a translation transformation on the current matrix and

returns the resulting matrix.

-

-

float x

The distance to translate along the x-axis.

-

float y

The distance to translate along the y-axis.

-

The resulting matrix.

- SVGMatrix scale(float scaleFactor)

-

Post-multiplies a uniform scale transformation on the current matrix

and returns the resulting matrix.

-

-

float scaleFactor

Scale factor in both X and Y.

-

The resulting matrix.

- SVGMatrix scaleNonUniform(float scaleFactorX, float scaleFactorY)

-

Post-multiplies a non-uniform scale transformation on the current matrix

and returns the resulting matrix.

-

-

float scaleFactorX

Scale factor in X.

-

float scaleFactorY

Scale factor in Y.

-

The resulting matrix.

- SVGMatrix rotate(float angle)

-

Post-multiplies a rotation transformation on the current matrix and

returns the resulting matrix.

-

-

float angle

Rotation angle.

-

The resulting matrix.

- SVGMatrix rotateFromVector(float x, float y)

-

Post-multiplies a rotation transformation on the current matrix and

returns the resulting matrix. The rotation angle is determined by taking

(+/-) atan(y/x). The direction of the vector (x, y) determines whether

the positive or negative angle value is used.

-

-

float x

The X coordinate of the vector (x,y). Must not be zero.

-

float y

The Y coordinate of the vector (x,y). Must not be zero.

-

The resulting matrix.

-

- InvalidAccessError

- Raised if one of the

parameters has an invalid value.

- SVGMatrix flipX()

-

Post-multiplies the transformation [-1 0 0 1 0 0] and returns the

resulting matrix.

-

The resulting matrix.

- SVGMatrix flipY()

-

Post-multiplies the transformation [1 0 0 -1 0 0] and returns the

resulting matrix.

-

The resulting matrix.

- SVGMatrix skewX(float angle)

-

Post-multiplies a skewX transformation on the current matrix and

returns the resulting matrix.

-