Abstract

This module describes features often used in printed publications. Most

of the specified functionality involves some sort of generated content

where content from the document is adorned, replicated, or moved in the

final presentation of the document. Along with two other CSS3 modules

– multi-column layout and paged media – this module offers

advanced functionality for presenting structured documents on paged media.

Paged media can be printed, or presented on screens.

Status of this

document

This section describes the status of this document at the time of

its publication. Other documents may supersede this document. A list of

current W3C publications and the latest revision of this technical report

can be found in the W3C technical reports

index at http://www.w3.org/TR/.

Publication as a Working Draft does not imply endorsement by the W3C

Membership. This is a draft document and may be updated, replaced or

obsoleted by other documents at any time. It is inappropriate to cite this

document as other than work in progress.

The (archived) public

mailing list www-style@w3.org (see

instructions) is preferred

for discussion of this specification. When sending e-mail, please put the

text “css3-gcpm” in the subject, preferably like this:

“[css3-gcpm] …summary of

comment…”

This document was produced by the CSS Working Group (part of

the Style Activity).

This document was produced by a group operating under the 5 February

2004 W3C Patent Policy. W3C maintains a public list of any patent disclosures made in

connection with the deliverables of the group; that page also includes

instructions for disclosing a patent. An individual who has actual

knowledge of a patent which the individual believes contains Essential

Claim(s) must disclose the information in accordance with section

6 of the W3C Patent Policy.

This WD contains functionality that the CSS WG finds interesting and

useful. In general, the earlier a feature appears in this draft, the more

stable it is. Significant changes in functionality and syntax must be

expected from paged presentations and

onwards. Also, functionality described in this module may be moved to

other modules. Since the previous WD,

hyphenation has been moved to css3-text

and the super-decimal

list-style-type value has been moved to css3-lists.

Named

counter styles and the symbols()

list-style-type value should also appear in a future css3-lists WD.

1. Introduction

(This section is not normative.)

This specification describes features often used in printed

publications. Some of the proposed functionality (e.g., the new list style

types, and border segments) may also used with other media types. However,

this specification is monstly concerned with paged media.

To aid navigation in printed material, headers and footers are often

printed in the page margins. [CSS3PAGE] describes how to place

headers and footers on a page, but not how to fetch headers and footers

from elements in the document. This specification offers two ways to

achieve this. The first mechanism is named

strings which copies the text (without style, structure, or

replaced content) from one element for later reuse in margin boxes. The

second mechanism is running elements which

moves elements (with style, structure, and replaced content) into

a margin box.

2.1. Named strings

Named strings can be thought of as variables that can hold one string of

text each. Named strings are created with the ‘string-set’

property which copies a string of text into the named string. Only text is

copied; not style, structure, or replaced content.

Consider this code:

h1 { string-set: title content() }

Whenever an h1 element is encountered, its textual content

is copied into a named string called title. Its content can be

retrieved in the ‘content’

property:

@page :right { @top-right { content: string(title) }}

2.1.1.

Setting named strings: the ‘string-set’ property

| Name:

| string-set

|

| Value:

| [[ <identifier> <content-list>] [, <identifier>

<content-list>]* ] | none

|

| Initial:

| none

|

| Applies to:

| all elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| N/A

|

| Media:

| all

|

| Computed value:

| as specified value

|

The ‘string-set’ property accepts a

comma-separated list of named strings. Each named string is followed by a

content list that specifies which text to copy into the named string.

Whenever an element with value of ‘string-set’ different from ‘none’ is encountered, the named strings are

assigned their respective value.

For the ‘string-set’ property, <content-list>

expands to one or more of these values, in any order:

- <string>

- a string, e.g. "foo"

- <counter>

- the counter() or counters() function, as per CSS 2.1 section

4.3.5

- <content>

- the ‘

content()’ function returns

the content of elements and pseudo-elements. The functional notation

accepts an optional argument:

- ‘

content()’

- Without any arguments, the function returns the textual content of

the element, not including the content of its ::before and ::after

pseudo-element. The content of the element's descendants, including

their respective ::before and ::after pseudo-elements, are included in

the returned content.

- ‘

content(before)’

- The function returns the textual content of the ::before

pseudo-element the content of the element.

- ‘

content(after)’

- The function returns the textual content of the ::after

pseudo-element the content of the element.

- ‘

content(first-letter)’

- The function returns the first letter of the content of the element.

The definition of a letter is the same as for :first-letter

pseudo-elements.

The expected use for ‘content(first-letter)’ is to create one-letter

headers, e.g., in dictionaries.

- ‘

env()’

- This function returns data from the local environment of the user at

the time of formatting. The function accepts one of these keywords:

- env(url): returns the URL of the document

- env(date): returns the date on the user's system at the time of

formatting

- env(time): returns the time on the user's system at the time of

formatting

- env(date-time): returns the date and time on the user's system at

the time of formatting

Information about date and time is formatted according to the locale

of the user's system.

Or, should there be a way to specify the locale? Or

should we simply format all in ISO format (e.g., 2010-03-30)?

On many systems, preformatted strings in the user's

locale can be found through the strftime

function. The date, time and date-time strings can be found by using

the "%x", "%X" and "%c" conversion strings, respectively.

@page {

@top-right { content: env(url) }

@bottom-right { content: env(date-time) }

}

Named strings can only hold the result of one assignment; whenever a new

assignment is made to a named string, its old value is replaced.

User agents, however, must be able to remember the result of

more than one assignment as the ‘string()’ functional value (described below) can

refer to different assignments.

The scope of a named string is the page of the element to which the

‘string-set’ property is attached and

subsequent pages.

The name space of named strings is different from other sets of names in

CSS.

The ‘string-set’ property copies text as well

as white-space into the named string.

h2 {

string-set: header "Chapter " counter(header) ": " content();

counter-increment: header;

}

Note that the string called "header" is different from the counter with

the same name. The above code may result in header being set to

"Chapter 2: Europa".

This example results in the same value being assigned to

header as in the previous example.

h2:before { content: "Chapter " counter(header) }

h2 {

string-set: header content(before) content();

counter-increment: header }

dt { string-set: index content(first-letter) }

The content is copied regardless of other settings on the element. In

HTML, TITLE elements are normally not displayed, but in this examplet the

content is copied into a named string:

title {

display: none;

string-set: header content();

}

2.1.2. Using named

strings

The content of named strings can be recalled by using the ‘string()’ value on the ‘content’ property. The ‘string()’ value has one required argument, namely

the name of the string.

@page { @top-center { content: string(header) }}

@page { @right-middle { content: string(index) }}

@page { @top-left { content: string(entry) }}

h1 { string-set: header "Chapter " counter(chapter) content() }

dt { string-set: index content(first-letter), entry content() }

If the value of the named string is changed by an element on a certain

page, the named string may have several values on that page. In order to

specify which of these values should be used, an optional argument is

accepted on the ‘string()’ value. This

argument can have one of four keywords:

- ‘

start’: the named string's entry

value for that page is used.

- ‘

first’: the value of the first

assignment is used. If there is no assignment on the page, the start

value is used. ‘first’ is the default

value.

- ‘

last’: the named string's exit

value for that page is used

- ‘

first-except’: similar to

‘first’, except on the page where the

value was assigned. On that page, the empty string is used.

The assignment is considered to take place on the first page where a

content box representing the element occurs. If the element does not have

any content boxes (e.g., if ‘display:

none’ is set), the assignment is considered to take place on

the page where the first content box would have occured if the element had

been in the normal flow.

In this example, the first term on the page will be shown in the top

left corner and the last term on the page will be shown in the top right

corner. In top center of the page, the first letter of first term will be

shown.

@page { @top-left { content: string(term, first) }}

@page { @top-right { content: string(term, last) }}

@page { @top-center { content: string(index, first) }}

dt { string-set: index content(first-letter), term content() }

In this example, the header in the top center will be blank on pages

where ‘h1’ elements appear. On other

pages, the string of the previous ‘h1’

element will be shown.

@page { @top-center { content: string(chapter, first-except) }}

h1 { string-set: chapter content() }

If the named string referred to in a ‘string()’ value has not been assigned a value, the

empty string is used.

2.2. Running elements

Named strings, as described above, can only hold textual content; any

style, structure or replaced content associated with the element is

ignored. To overcome this limitation, a way of moving elements into

running headers and footers is introduced.

Elements that are moved into headers and footers are repeated on several

pages; they are said to be running

elements. To support running elements, a new value –

running() – is introduced on the ‘position’ property. It has one required

argument: the name by which the running element can be referred to. A

running element is not shown in its natural place; there it is treated as

if ‘display: none’ had been set.

Instead, the running element may be displayed in a margin box.

Like counters and named strings, the name of a running element is chosen

by the style sheet author, and the names have a separate name space. A

running element can hold one element, including its pseudo-elements and

its descendants. Whenever a new element is assigned to a running element,

the old element is lost.

User agents, however, must be able to remember the result of

more than one assignment as the ‘element()’ value (described below) can refer to

different assignments.

Running elements inherit through their normal place in the structure of

the document.

title { position: running(header) }

@page { @top-center {

content: element(header) }

}

Like the ‘string()’ value, the

‘element()’ value accepts an optional

second argument:

- ‘

start’

- ‘

first’

- ‘

last’

- ‘

first-except’

The keywords have the same meaning as for the ‘string()’ value, and the place of the assignments

are the same.

The ‘element()’ value cannot be

combined with any other values.

In this example, the header is hidden from view in all media types

except print. On printed pages, the header is displayed top center on all

pages, except where h1 elements appear.

<style>

div.header { display: none }

@media print {

div.header {

display: block;

position: running(header);

}

@page { @top-center { content: element(header, first-except) }}

</style>

...

<div class="header">Introduction</div>

<h1 class="chapter">An introduction</div>

This code illustrates how to change the running header on one page in

the middle of a run of pages:

...

<style>

@page { @top-center {

content: element(header, first) }}

.header { position: running(header) }

.once { font-weight: bold }

</style>

...

<div class="header">Not now</div>

<p>Da di ha di da di ...

<span class="header once">NOW!</span>

<span class="header">Not now</span>

... da di ha di hum.</p>

...

The header is "Not now" from the outset, due to the "div" element. The

first "span" element changes it to "

NOW!" on the page where the

"span" element would have appeared. The second "span" element, which would

have appeared on the same page as the first is not used because the

‘

first’ keyword has been specified.

However, the second "span" element still sets the exit value for "header"

and this value is used on subsequent pages.

3. Leaders

A leader is a visual pattern that guides the eye. Typically, leaders are

used to visually connect an entry in a list with a corresponding code. For

example, there are often leaders between titles and page numbers in a

table of contents (TOC). Another example is the phone book where there are

leaders between a name and a telephone number.

In CSS3, a leader is composed of series of glyphs through the

‘leader()’ value on the ‘content’ property. The functional notation

accepts two values. The first describes the glyph pattern that makes up

the leader. These values are allowed:

- leader(dotted)

- leader(solid)

- leader(space)

- leader(<string>)

Using the keyword values is equivalent to setting a string value. The

table below shows the equivalents:

| Keyword

| String

| Unicode characters

|

| leader(dotted)

| leader(‘. ’)

| \002E \0020

|

| leader(solid)

| leader(‘_’)

| \005F

|

| leader(space)

| leader(‘ ’)

| \0020

|

The string inside the parenthesis is called the leader string.

In its simplest form, the ‘content’ property only takes one ‘leader()’ value:

heading::after { content: leader(dotted) }

The leader string must be shown in full at least once and this

establishes the minimum length of the leader. To fill the available space,

the leader string is repeated as many times as possible in the writing

direction. At the end of the leader, a partial string pattern may be

shown. White space in leaders is collapsed according to the values on

white-space properties.

These properties influence the appearance of leaders: all font

properties, text properties, ‘letter-spacing’, white-space properties,

background properties, and ‘color’.

The second value describes the alignment of the leader. These values are

allowed:

- align

- attempt to align corresponding glyphs from the leader pattern between

consecutive lines. This is the default value.

- start

- align leader string with the start

- end

- align leader string with the end

- center

- center leader string

- string-space

- add space between strings to take up all available space

- letter-space

- add space between letters (both inside the string, and at the

start/end of the string) to take up all available space

heading::after { content: leader(dotted, align) }

heading::after { content: leader(dotted, start) }

heading::after { content: leader(dotted, end) }

heading::after { content: leader(dotted, center) }

heading::after { content: leader(dotted, string-space) }

heading::after { content: leader(dotted, letter-space) }

In a more complex example, the ‘leader’ value is combined with other values on

the ‘content’ property:

ul.toc a::after {

content: leader(". . . ") target-counter(attr(href, url), page);

}

If the content connected by a leader end up on different lines, the

leader will be present on all lines. Each leader fragment honors the

minimum length of the leader.

Consider this code:

<style>

.name::after { content: leader(dotted) }

</style>

<div class="entry">

<span class="name">John Doe</span>

<span class="number">123456789</span>

</div>

If the name and number end up on different lines (e.g., in a narrow

column), it may be formatted like this:

John Doe....

...123456789

To determine the length of the leaders, user agents must do the

following for each line:

- Lay out the content with leaders of minimum lengths

- Determine the empty space left on the line.

- Distribute the empty space between the leaders on the line. Glyphs

must not be shown partially. All leaders on the line should, to the

extent possible, have the same length. This may not always be possible as

the minimum leader length must be honored.

- Fill the empty space with the specified leader pattern.

Consider this code:

<style>

cite::before { content: leader(' ') }

</style>

<blockquote>

Bla great bla bla world bla bla

empire bla bla color bla bla

history bla bla forever.

<cite>John Johnson</cite>

</blockquote>

Depending on the width of the containing block, this may be rendered

as:

Bla great bla bla world bla bla

empire bla bla color bla bla

history bla bla forever. John

Johnson

However, this rendering is preferable:

Bla great bla bla world bla bla

empire bla bla color bla bla

history bla bla forever.

John Johnson

To indicate that John Johnson

should be kept on one line, this

rule can be added to the style sheet:

cite { text-wrap: suppress }

Until ‘text-wrap’ is widely

supported, this rule can also be used:

cite { white-space: nowrap }

If the containing element is wider, this may be the resultant

presentation:

Bla great bla bla world bla bla empire

bla bla color bla bla history bla bla

forever. John Johnson

4. Cross-references

It is common to refer to other parts of a document by way of a section

number (e.g., "See section 3.4.1"), a page number (e.g., "See discussion

on page 72"), or a string (e.g., "See the chapter on Europe"). Being able

to resolve these cross-references automatically saves time and reduces the

number of errors.

4.1.

The ‘target-counter’ and

‘target-counters’ values

Numerical cross-references are generated by ‘target-counter()’ and ‘target-counters()’ values that fetch the value of a

counter at the target end of the link. These functions are similar to the

‘counter()’ and ‘counters()’ functions, except that they fetch

counter values from remote elements. ‘target-counter()’ has two required arguments: the

url of the link, and the name of a counter. ‘target-counters()’ has three required arguments:

the url of the link, the name of a counter, and a separator string. Both

functions accepts an optional argument at the end that describes which

list style type to use when presenting the resulting number; ‘decimal’ being the default.

This style sheet specifies that a string like " (see page 72)" is added

after a link:

a::after { content: "(see page " target-counter(attr(href, url), page, decimal) ")" }

This style sheet specifies that a string like " (see section 1.3.5)" is

added after a link:

a::after { content: "(see section " target-counters(attr(href, url), section, ".", decimal) ")" }

4.2. The ‘target-text’ value

Textual cross-references are generated by ‘target-text()’ which fetches the textual content

from the target end of the link. Only text is copied; not style,

structure, or replaced content. ‘target-text()’ has one required argument: the url

of the link. An optional second argument specifies exactly which content

is fetched. There are four possible values:

- ‘

content()’

- refers to the textual content of the element, not including the

content of its ::before and ::after pseudo-element. The content of the

element's descendants, including their respective ::before and ::after

pseudo-elements, are included in the returned content.

- ‘

content(before)’

- refers to the content of the element's ::before pseudo-element. This

is the default value.

- ‘

content(after)’

- refers to the content of the element's ::after pseudo-element

- ‘

content(first-letter)’

- refers to the first letter of the textual content of the element, not

including the content of its ::before and ::after pseudo-element.

To generate this text

See Chapter 3 ("A better way") on page 31 for an in-depth evaluation.

from this markup:

<p>See <a href="#chx">this chapter</a> for an in-depth evaluation.

...

<h2 id="chx">A better way</h2>

this CSS code can be used:

h2 { counter-increment: chapter }

a { content: "Chapter " target-counter(attr(href, url), chapter)

' ("' target-text(attr(href), content()) '") on page '

target-counter(attr(href, url), page);

A footnote is a note typically placed at the bottom of a page that

comments on or cites a reference. References to footnotes are marked with

a note-call in the main text. The rendering of footnotes is

complex. As far as possible, footnotes try to reuse other parts of CSS.

However, due to the typographic traditions of footnotes, some new

functionality is required to support footnotes in CSS:

In order to support footnotes in CSS, the following functionality is

added:

- one new value on the ‘

float’

property: ‘footnote’

- one new page area: ‘

@footnote’

- two new pseudo-elements: ‘

::footnote-call’ and ‘::footnote-marker’

- one predefined counter: ‘

footnote’

- one new value on the ‘

content’

property: ‘target-pull()’

- border segments

In its simplest form, making a footnote is simple.

<style>

.footnote { float: footnote }

</style>

<p>A sentence consists of words. <span class="footnote">Most often.</span>.

In this example, the text Most often.

will be placed in a

footnote. A note-call will be left behind in the main text and a

corresponding marker will be shown next to the footnote. Here is one

possible rendering:

A sentence consists of words. ¹

¹ Most often.

To support legacy browsers, it is often better to make a link to the

note rather than including the text inline. This example shows how to

fetch the content of a note and place it in a footnote.

<style>

@media print {

.footnote {

float: footnote;

content: target-pull(attr(href, url)) }

.call { display: none }

}

</style>

...

<p>A sentence consists of words<a class="footnote" href="#words"> [3]</a>.

...

<p id=words><span class="call">[3]</span> Most often.

When shown in a legacy browser, the content of the element will be

shown as a clickable link to an endnote. When printed according to this

specification, there will be a footnote:

A sentence consists of words¹.

¹ Most often.

Consider this markup:

<p>Sorry, <span title="This is, of course, a lie.">we're closing for lunch</span>.

The content of the "title" attribute can be turned into a footnote with

this code:

span[title]::after {

content: attr(title);

float: footnote;

}

An element with ‘float: footnote’

(called a footnote element) is moved to the footnote

area and a footnote-call pseudo-element is put in its

original place.

span.footnote {

float: footnote;

}

Footnote elements are presented inside the footnote area, but

they inherit through their normal place in the structure of the document.

The ‘display’ property on

footnote elements is ignored. Instead, the value of the ‘display’ property in the @footnote context

determines if footnotes are block or inline elements.

In this example, the footnotes are displayed inline:

@footnote {

display: inline;

}

span.footnote {

float: footnote;

}

Here is one possible presentation of inline footnotes:

¹ The first footnote. º The second footnote.

For each new footnote element, the ‘footnote’ counter is automatically incremented.

All elements with ‘float: footnote’

are moved to the footnote area. The footnote area is described by

an @footnote-rule inside the @page-rule. By default, the footnote area

appears at the bottom of the page, but it can be positioned in other

places.

Should the footnote are be positioned using page floats or

(fixed?) absolute positioning? Or both?

These rules place the footnote area at the bottom of the page, spanning

all columns:

@page {

@footnote {

float: bottom;

column-span: all;

width: 100%;

}

}

These rules place the footnote area at the bottom of the first column:

@page {

@footnote {

float: bottom;

width: 100%;

}

}

This code places the footnote area at the bottom of the right column:

@page {

@footnote {

float: bottom-corner;

width: 100%;

}

}

The content of the footnote area is considered to come before other

content which may compete for the same space on the same page.

@page { @footnote { float: bottom page}}

div.figure { float: bottom page }

If figures and footnotes are on the same page, the footnotes will

appear below the figures as they are floated to the bottom before the

figures.

Potentially, every page has a footnote area. If there are no footnotes

on the page, the footnote area will not take up any space. If there are

footnotes on a page, the layout of the footnote area will be determined by

the properties/values set on it, and by the footnote elements elements

inside it.

These properties apply to the footnote area: ‘content’, ‘border’, ‘padding’, ‘margin’, ‘height’, ‘width’, ‘max-height’, ‘max-width’, ‘min-height’, ‘min-width’, the background properties.

This example uses some of the applicable properties on @footnote:

@footnote {

margin-top: 0.5em;

border-top: thin solid black;

border-clip: 4em;

padding-top: 0.5em;

}

The result of this code is a footnote area separated from other content

above it by margin, border and padding. Only 4em of the border is visible

due to the ‘border-clip’

property, which is defined in CSS Backgrounds and

Borders Module Level 4. .

When an element is moved to the footnote area, a footnote-call

is left behind. By default, User Agents must behave as if this code is

part of the default style sheet:

::footnote-call {

content: counter(footnote, super-decimal);

}

The resulting note call is a super-script decimal number.

A ::footnote-marker pseudo-element is added to each footnote element, in

the same place, and replacing, the ::before pseudo-element. User agents

must, by default, show the "footnote" counter in the footnote-marker.

User Agents may display footnote-calls and footnote-markers this way by

default:

::footnote-call {

content: counter(footnote, super-decimal);

}

::footnote-marker {

content: counter(footnote, super-decimal);

}

Marker elements are discussed in more detail in the CSS Lists module [CSS3LIST]. One

suggested change to that module is to honor the value of ‘list-style-position’ on the ::footnote-marker

pseudo-element itself rather than the corresponding list-item element.

Further, one clarification to the horizontal placement of the marker is

suggested: the margin box of the marker box is horizontally

aligned with the start of the line box.

The "footnote" counter is automatically incremented each time a footnote

is generated. That is, the "footnote" counter is incremented by one each

time an element with ‘float: footnote’

appears.

The footnote counter can be reset with the ‘counter-reset’ property.

This code resets the "footnote" counter on a per-page

page basis:

@page { counter-reset: footnote }

Should one also be able to manually increment the "footnote"

counter?

Footnotes must appear as early as possible under the following

constraints:

- A footnote marker may not appear on an earlier page than the footnote

call.

- Footnotes may not appear out of document order.

- The footnote area is limited in size by ‘

max-height’, unless the page contains only

footnotes. (E.g., if at the end of the document there are still footnotes

unprinted, the User Agent can use the whole page to display footnotes.)

- If there is a footnote call on a page, the footnote area may not be

empty, unless its ‘

max-height’ is

too small.

When an element is turned into a footnote, certain magical things

happen. The element is moved to the footnote area, a footnote call is left

behind in its place, a footnote marker is displayed before the element,

and the footnote counter is incremented.

When rendering footnotes, User Agents may apply certain heuristics to

improve the presentation. For example, the space between a footnote-call

and surrounding text may be adjusted. Another example is the height of the

footnote area; it may be heuristically constrained to limit the area that

is used for footnotes.

6. Page marks and

bleed area

The ‘marks’

property from [CSS2] is

part of this specification.

| Name:

| marks

|

| Value:

| [ crop || cross ] | none

|

| Initial:

| none

|

| Applies to:

| page context

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| N/A

|

| Media:

| visual, paged

|

| Computed value:

| specified value

|

This property adds crop and/or cross marks to the document. Crop marks

indicate where the page should be cut. Cross marks are used to align

sheets.

Crop marks and cross marks are printed outside the page box. To have

room to show crop and cross marks, the final pages will have to be

somewhat bigger than the page box.

To set crop and cross marks on a document, this code can be used:

@page { marks: crop cross }

| Name:

| bleed

|

| Value:

| <length>

|

| Initial:

| 6pt

|

| Applies to:

| page context

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| refer to width of page box

|

| Media:

| visual

|

| Computed value:

| as specified value

|

This property specifies the extent of the page bleed area outside the

page box. This property only has effect if crop marks are enabled.

7. Bookmarks

Some document formats have the capability of holding bookmarks.

Bookmarks are typically shown outside the document itself, often a

tree-structured and clickable table of contents to help navigate in the

electronic version of the document. To generate bookmarks, these

properties are defined:

| Name:

| bookmark-level

|

| Value:

| none | <integer>

|

| Initial:

| none

|

| Applies to:

| all elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| N/A

|

| Media:

| all

|

| Computed value:

| specified value

|

This property describes what level a certain bookmark has in a

hierarchical bookmark structure. The highest level is ‘1’, then ‘2’,

‘3’ etc.

h1 { bookmark-level: 1 }

h2 { bookmark-level: 2 }

h3 { bookmark-level: 3 }

| Name:

| bookmark-label

|

| Value:

| content() | <string>

|

| Initial:

| content()

|

| Applies to:

| all elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| N/A

|

| Media:

| all

|

| Computed value:

| specified value

|

This property specifies the label of the bookmark, i.e., the text that

will represent the bookmark in the bookmark structure.

a { bookmark-label: attr(title, string) }

h1 { bookmark-label: content() }

h2 { bookmark-label: content(before) }

#frog { bookmark-label: "The green frog" }

| Name:

| bookmark-target

|

| Value:

| none | <uri>

|

| Initial:

| none

|

| Applies to:

| all elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| N/A

|

| Media:

| all

|

| Computed value:

| For URI values, the absolute URI; for ‘none’, as specified.

|

This property specifies the target of the bookmark link.

.bookmark {

bookmark-label: attr(title, string);

bookmark-target: attr(href, url);

}

...

<a class="bookmark" title="The green pear" href="#pears"/>

.exable { bookmark-label: url(http://www.example.com) }

| Name:

| bookmark-state

|

| Value:

| open | closed

|

| Initial:

| open

|

| Applies to:

| block-level elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| N/A

|

| Media:

| all

|

| Computed value:

| specified value

|

This property describes the initial state of a bookmark.

* { bookmark-state: closed }

#open { bookmark-state: open }

8. CMYK colors

Printers do not use RGB colors, they (often) use CMYK: cyan, magenta,

yellow and black. The ‘device-cmyk()’

functional value allows style sheets to express device-dependent CMYK

colors.

h3 { color: device-cmyk(0.8, 0.5, 0.0, 0.3) }

The values representing the colors are between ‘0’ and ‘1’.

Values outside this range are clipped.

It is not expected that screen-centric user agents support CMYK colors

and it is therefore important that existing CSS color values can be

combined with CMYK colors.

h3 {

color: red;

color: device-cmyk(0.5, 0.1, 0.0, 0.2);

}

User Agents that do not understand the device-cmyk()

value, will use the first color (red). User agents that understand

device-cmyk() will use the second color (which is bluish).

9. Styling blank pages

Blank pages that appear as a result of forced page breaks can be styled

with the :blank pseudo-class.

In this example, forced page break may occur before h1

elements.

h1 { page-break-before: left }

@page :blank {

@top-center { content: "This page is intentionally left blank" }

}

The :blank pseudo-class has the same specificity as the

:first pseudo-class. A page matched by :blank

will still be matched by other page selectors.

If headers have been specified on all right pages, a blank right page

will be matched by both :blank and :right.

Therefore, margin boxes set on right pages will have to be removed unless

they are wanted on blank pages. Here is an example where the top center

header is removed from blank pages, while the page number remains:

h1 { page-break-before: left }

@page :blank {

@top-center { content: none }

}

@page :right {

@top-center { content: "Preliminary edition" }

@bottom-center { content: counter(page) }

}

Due to the higher specificity of :blank over

:right, the top center header is removed even if

content: none comes before content: "Preliminary

edition".

10. Paged presentations

Printed publications are paged, while screen-based presentations of web

pages are most often presented in a continous manner with a scrollbar on

the side. There are reasons to believe that screen-based presentations

also could benefit from using paged presentations. There is nothing in web

specifications that prevent browsers from adding a page-based mode today.

However, most web content is authored and styled with a continous

presentation in mind. This could change if it becomes possible to describe

paged presentations in style sheets. This section is an attempt to do so.

To support paged presentations, four new values are added to the

‘overflow-style’ property:

- paged-x

- overflow content is paged, and the pages are laid out along the x

axis, in the x axis component of the writing direction

- paged-y

- overflow content is paged, and the pages are laid out along the y

axis, in the the y axis component of the writing direction

- paged-x-controls

- as ‘

paged-x’, but with added

UA-specific controls to change pages

- paged-y-controls

- as ‘

paged-y’, but with added

UA-specific controls to change pages

Is "paginated" a better word?

Should controls be specified on a separate property, or on

an attribute (like HTML's video element)?

Should the axis (x/y) be specified on a separate property?

In this example, the root element is constrained to have the same

height as the initial containing block. Overflow content will be laid out

on subsequent pages along the x axis. In LTR languages, this means right;

in RTL languages this means left; in vertical-rl this means right.

html {

overflow-style: paged-x;

height: 100%;

}

In this example, one element within the document is paged, and controls

are added so that users can navigate from one page to the next. As such,

the controls have the same effect as scrollbars in continous

presentations.

#content {

overflow-style: paged-x-controls;

height: 400px;

}

A paged container cannot be split over multiple columns.

11. Navigation

between pages

Paged navigation within a page (as described above), can also be

naturally extended to navigation between web documents. To support this, a

new @-rule is proposed: @navigation. The purpose of @navigation is to

describe which documents the user can navigate to by moving up, right,

down, or left from the current document.

Four new properties are allowed inside @navigation: nav-up, nav-right,

nav-bottom, nav-right.

The name of the properties inside @navigation are borrowed

from CSS3

Basic User Interface Module.

The properties accept these values:

- link-rel()

- the function takes one argument, which refers to the rel

attribute of the link element

<link rel=index href="../index.html">

<link rel=previous href=g3.html>

<link rel=next href=g1.html>

...

@-o-navigation {

nav-up: link-rel(index);

nav-left: link-rel(previous);

nav-right: link-rel(next);

}

This functionality relies on semantics in HTML and CSS.

Other languages may have other other ways to describe such semantics.

One possible solution for other languages is "link[rel=index] { nav-up:

attr(href) }"

The "link-rel" name is a bit academic, perhaps the "go()"

name can be used instead?

- go()

- The function takes one argument: back, which takes the user

one step back in history.

@navigation {

nav-left: go(back);

}

-

- url-doc()

- The funcation takes one argument: a URL. Relative URLs are relative to

the document, not to the style sheet.

@navigation {

nav-up: url-doc(..);

nav-down: url-doc(a1.html);

}

- url()

- The funcation takes one argument: a URL. Relative URLs are relative to

the style sheet.

@navigation {

nav-up: url(..);

nav-down: url(a1.html);

}

Combined with the @document-rule,

navigation maps can be described:

@document url("http://example.com/foo") {

@navigation {

nav-right: link-rel(next);

}

}

@document url("http://example.com/bar") {

@navigation {

nav-upt: link-rel(next);

}

}

11.1. Page shift effects

To describe page shift effects, four new properties inside @navigation

are proposed: nav-up-shift, nav-right-shift, nav-down-shift,

nav-left-shift. These properties take one of several keyword values:

- pan

- pans to the new page; this is the initial value

- turn

- turns the page, like soft book pages do

- flip

- flips the page, like stiff cardbord

- fold

- the old page folds, like an accordion

The proposed keyword values are loosely described. Are there

better ways to describe transitions?

@navigation {

nav-up-shift: pan;

nav-down-shift: flip;

}

12. Page floats

Images and figures are sometimes displayed at the top or bottom of pages

and columns. This specificaton adds new keywords on the ‘float’ property which, in combination with

integer values on ‘column-span’

and the new ‘float-modifier’,

provides support for common paper-based layouts.

Four new keywords on ‘float’

have been added:

- top

- the box is floated to the top of the natural column

- bottom

- the box is floated to the bottom of the natural column

- top-corner

- the box is floated to the top of the last column (in the inline

direction) that fits inside the multicol element on the same page.

- bottom-corner

- similar to ‘

top-corner’, exept

the box is floated to the bottom

- snap

- same as ‘

top’ if the box is

naturally near the top; same as ‘bottom’ if the box is naturally near the

bottom. The ‘widows’/‘orphans’ properties may be consulted to

determine if the box is near the top/bottom.

These new keywords only apply in paged media; in continous media

declarations with these keywords are ignored.

Float figure to top of natural column:

.figure { float: top; display: block; }

.figure { float: top; width: 50% }

Float figure to top of the natural column, spanning all columns:

.figure { float: top; column-span: all }

Float figure to top/bottom of the last column of the multicol element

on that page:

.figure { float: top-corner }

The ‘column-span’ property is

extended with integer values so that elements can span several columns. If

the specified integer value is equal to, or larger than the number of

columns in the multicol element, the number of columns spanned will be the

same as if ‘column-span: all’ had been

specified.

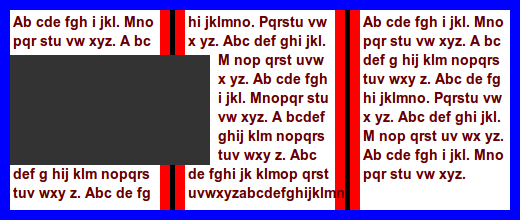

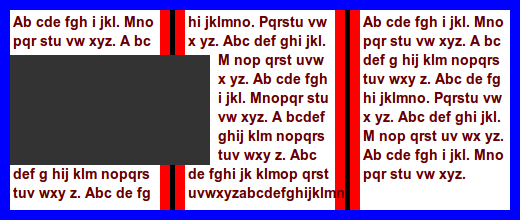

In combination with ‘column-span’, the figure is floated to the

top corner of the multicol element on that page:

.figure { float: top-corner; column-span: 2; width: 100% }

body { columns: 3 }

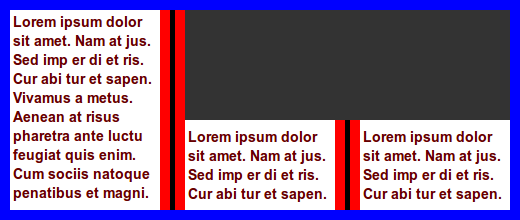

img.A { column-span: 2; width: 100% }

.one { column-span: 2 }

12.1. Float modifiers

These values on ‘float’ can be

combined with one of ‘top’/‘bottom’/‘top-corner’/‘bottom-corner’ values:

- next-page

- In paged media, float box to the next page. The first column of the

multicol element on the next page is considered to be the natural column

for boxes affected by this value.

.figure { float: top-corner next-page }

- next-column

- In paged media, float box to the next column.

.figure { float: top next-column }

.figure { float: next-column top }

- unless-room

- Only float the box if it otherwise would have lead to a column or page

break.

.figure { float: top unless-room }

- left/right

- ‘

left’/‘right’ can be used in combination with

‘top’/‘bottom’/‘top-corner’/‘bottom-corner’ to allow other content to flow

around the box.

.figure { float: top right; width: 60% }

12.2.

Floating inside and outside pages

Two allow content to flow to the inside and outside of a page, these

keywords are added to the ‘float’

property:

- inside

- On a right page, this value is synonymous with ‘

left’. On a left page, this value is

synonymous with ‘right’.

- outside

- On a left page, this value is synonymous with ‘

left’, On a right page, this value is

synonymous with ‘right’.

.figure { float: outside }

12.3.

Multi-column float intrusion

A new value on ‘float’ is

introduced to support intrusion in columns:

- intrude

- The element may intrude neighboring columns; if the element is not in

a multi-column element, this keyword has no effect.

The ‘intrude’ value only works

in combination with one of these keywords: ‘left’/‘right’/‘top’/‘bottom’/‘top-corner’/‘bottom-corner’.

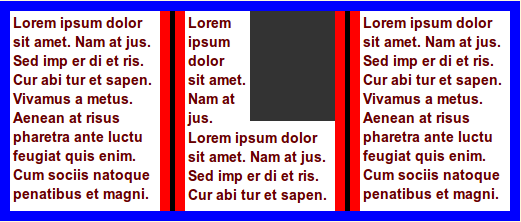

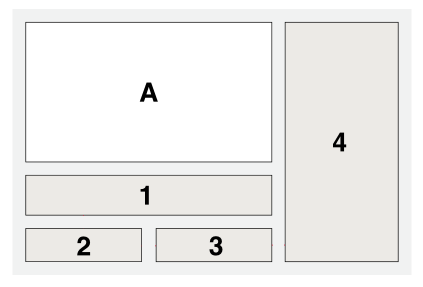

img { float: left intrude; width: 120%; }

In this example, the image is wider than the column and will therefore

intrude into the neighboring column. At the bottom of the middle column

is a long word that is clipped in the middle of the column gap.

| Name:

| float-offset

|

| Value:

| <length> <length> ?

|

| Initial:

| 0 0

|

| Applies to:

| floated elements

|

| Inherited:

| no

|

| Percentages:

| see prose

|

| Media:

| visual, paged

|

| Computed value:

| one or two absolute lengths

|

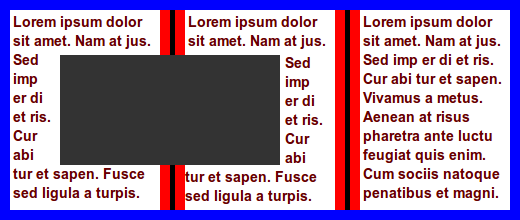

This property pushes a float in opposite direction of the where it has

been floated with ‘float’. If one

value is specified, it is the horizontal offset. If two values are

specified, the first is the horizontal and the second is the vertical

offset. If no vertical value has been specified, the vertical offset is

set to zero.

Negative values are allowed; a negative values will push the float in

the same direction as it has been floated with ‘float’

The float will never be pushed outside the content edges of the multicol

element due to a setting on ‘float-offset’.

Percentage values refer to the width/height of the float plus a fraction

of the column gap.

Floats that are moved into other columns with this property intrudes.

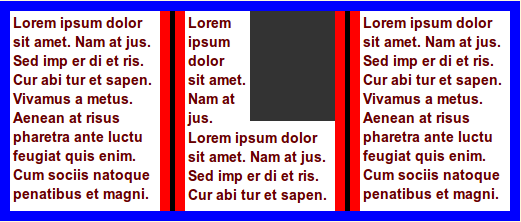

img {

float: top right;

float-offset: -50% 3em;

width: 120%;

}

img {

float: top right;

float-offset: -80% 2em;

width: 100%;

}

Would it make more sense to not specify the opposite

direction, but the "forward" direction?

13. The

‘first-page’ pseudo-element

The ‘first-page’ pseudo-element

is used to apply styling to the part of an element that ends up on the

starting page for that element. If the whole element appears on the

starting page, ‘first-page’

applies to the whole element. The following properties apply to

:first-page pseudo-elements: column properties, background properties,

margin properties, border properties, and padding properties. UAs may

apply other properties as well.

In this example, there will be one column on the starting page of each

chapter, while subsequent pages will have two columns:

div.chapter { columns: 2 }

div.chapter::first-page { columns: 1 }

In this example, padding is added on the left side on the starting page

of each chapter:

div.chapter { break-before: left }

div.chapter::first-page { padding-left: 4em }

14. Selecting

columns and pages

This is sketchy.

Pseudo-elements are introduced to apply styling to the part of an

element that ends up on a certain page of column of that element. The

‘column(n)’ pseudo-element selects

columns, and the ‘page(n)’

psedo-element select columns.

div.chapter::column(3) /* the third column of the element */

div.chapter::column(2n) /* all even columns of the element */

div.chapter::page(2) /* second page of the element */

div.chapter::page-column(2,2) /* second column on second page */

div.chapter::page(2)::column(2) /* second column, but only if it appears on the second page */

TBD

16. Appendix

A: Default style sheet

@page {

counter-reset: footnote;

@footnote {

counter-increment: footnote;

float: page bottom;

width: 100%;

height: auto;

}

}

::footnote-call {

counter-increment: footnote;

content: counter(footnote, super-decimal);

}

::footnote-marker {

content: counter(footnote, super-decimal);

}

h1 { bookmark-level: 1 }

h2 { bookmark-level: 2 }

h3 { bookmark-level: 3 }

h4 { bookmark-level: 4 }

h5 { bookmark-level: 5 }

h6 { bookmark-level: 6 }

Acknowledgments

This document has been improved by Bert Bos, Michael Day, Melinda Grant,

David Baron, Markus Mielke, Steve Zilles, Ian Hickson, Elika Etemad,

Laurens Holst, Mike Bremford, Allan Sandfeld Jensen, Kelly Miller, Werner

Donné, Tarquin (Mark) Wilton-Jones, Michel Fortin, Christian Roth,

Brady Duga, Del Merritt, Ladd Van Tol, Tab Atkins Jr., Jacob Grundtvig

Refstrup, James Elmore, Ian Tindale, Murakami Shinyu, Paul E. Merrell,

Philip Taylor, Brad Kemper, Peter Linss, Daniel Glazman, Tantek

Çelik, Florian Rivoal, Alex Mogilevsky.

References

Normative references

-

- [CSS3LIST]

- Tab Atkins Jr. CSS Lists

and Counters Module Level 3. 24 May 2011. W3C Working Draft.

(Work in progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2011/WD-css3-lists-20110524

Other references

-

- [CSS2]

- Ian Jacobs; et al. Cascading Style

Sheets, level 2 (CSS2) Specification. 11 April 2008. W3C

Recommendation. URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2008/REC-CSS2-20080411

- [CSS3PAGE]

- Håkon Wium Lie; Melinda Grant. CSS3 Module:

Paged Media. 10 October 2006. W3C Working Draft. (Work in

progress.) URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/2006/WD-css3-page-20061010

Index

- bleed, 6.

- bookmark-label, 7.

- bookmark-level, 7.

- bookmark-state, 7.

- bookmark-target, 7.

- float-offset, 12.4.

- marks, 6.

- named strings, 2.

- running elements, 2.

- string-set, 2.1.1.

Property index

| Property

| Values

| Initial

| Applies to

| Inh.

| Percentages

| Media

|

| bleed

| <length>

| 6pt

| page context

| no

| refer to width of page box

| visual

|

| bookmark-label

| content() | <string>

| content()

| all elements

| no

| N/A

| all

|

| bookmark-level

| none | <integer>

| none

| all elements

| no

| N/A

| all

|

| bookmark-state

| open | closed

| open

| block-level elements

| no

| N/A

| all

|

| bookmark-target

| none | <uri>

| none

| all elements

| no

| N/A

| all

|

| float-offset

| <length> <length> ?

| 0 0

| floated elements

| no

| see prose

| visual, paged

|

| marks

| [ crop || cross ] | none

| none

| page context

| no

| N/A

| visual, paged

|

| string-set

| [[ <identifier> <content-list>] [, <identifier>

<content-list>]* ] | none

| none

| all elements

| no

| N/A

| all

|