Date: January 1998

Status: personal view. Editing status: Spellchecked.

The web is a very general concept -- one universal space of information. The concepts it requires such as identifiers and information resources (documents) are as general and abstract as possible. However, there have been some design decisions made which define some interfaces, and effectively define modules or agents which are independent. These agents are independent in many ways

This is basic modularity. The interfaces are defined by the data formats and protocols, and the important features to understand about the design I have ranted about in the linked articles in this series. This modularity, ability for different parts of the system, shows up when different specs are independent, such that you could change one without having to change the other.

(Formerly, Resource)

This is the current term for a certain unit of information in the Web. In many cases on the current Web, thinking "document" will do. It is something which conveys information. The Web model is that information in the information space is in the abstract chunked into addressable things known as resources.

In the technical architecture, resources have identifiers, Universal Resource Identifiers, and the properties of these identifiers are elaborated later. In fact the concept of a unit of information is central, not only in the technical architecture, but in society's concepts of information, as a document is not only the unit for reference, retrieval and presentation (typically), but also the unit of ownership, license to use, payment, confidentiality, endorsement, etc. So though technically we can derive such things as compound document, generic documents, and resources which look anything but the typical notion of a "document", we have to be able to support these social aspects of information at the same time, so we can't mess with it too much.

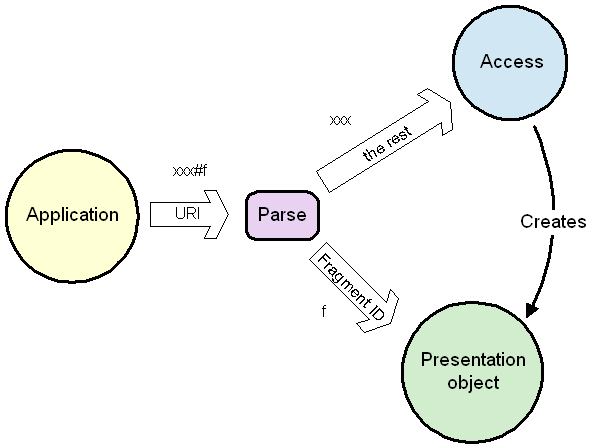

In the hypertext architecture, when making a reference, such as a hypertext link, we don't just refer to an information resource. Well, we can, but we can also refer to a particular part of or view of a resource. The string which, within the document, defines the other end of the link has two parts. It has the identifier of the document as a whole, and then optionally it has a hash sign "#" and a string representing the view of the object required. This suffix is called a fragment identifier. (Even though it doesn't represent necessarily a fragment of the document: it could represent how the document should be viewed.). The fragment identifier only has relevance in the context of the web page in question. This has an implication how the software is built. For example, An "access" module can be given just the bit of the URI without the fragment identifier. It gets the information, and creates a software object for the hypertext page. That object is passed the fragment identifier.

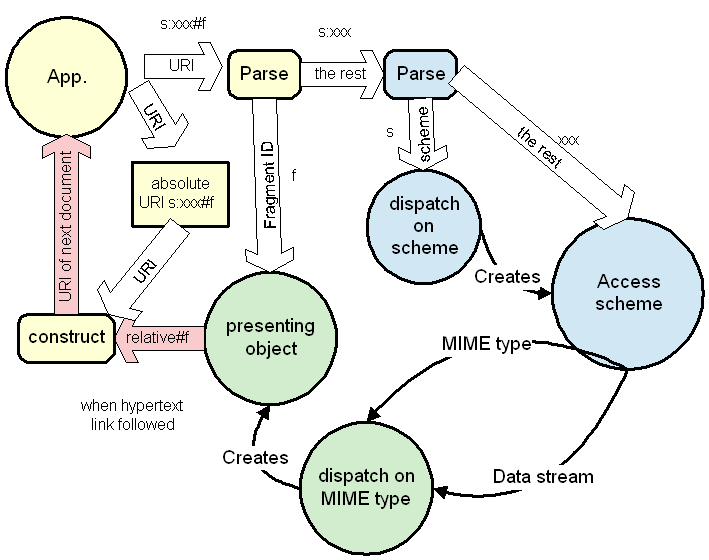

In fact, analyzing the system a little more, the access function can be broken into the underlying access which creates the object by passing two things to some kind of object creator ("factory"): a data stream and a MIME type.

Hypertext is a specific application, but this principle works for other applications on the Web. In fact, when we discuss webizing an application, we take some computer language, and we take what were document-global things, say global variables in a programming language, and make them truly global by appending the URI of the document and "#".

Clearly, in different applications the fragment identifier will have completely different function. The independence here means that new applications (such as the Semantic Web) can be built, just like hypertext web, just by introducing new types of document.

The model of how the web works is that there are two separate functions. The part (blue in the picture) which accesses the document deals with its identifier, but does not know what view will be required. It creates some software object which represents and presents the resource. That object does not need to know how it was created (necessarily), and so does not need to know the URI it was identified by. However, it does know how to interpret the Fragment ID.

So we have two axioms:

| The access machinery does not need to look at the fragment ID. |

| The presentation object does not need to know the URI of the resource |

The equivalent axioms when we are talking about specifications amount to:

| The specifications for access protocols are independent of the specifications for fragment identifiers. |

For one thing, consider the special case of a link within a document. In this case, the link only specifies a fragment identifier. The object can follow the link itself. It doesn't have to consult the access code in order to figure out where the link goes to. Because the "#" syntax s universal to all access methods, the object can process the link internally. For a static HTML file, for example, this means that you can write and HTMl file with internal links without worrying or knowing about exactly what URIs the file will get. It means you don't have to alter the file if you chose to serve it in some new name or address space. If the "#" syntax was not a universal specification for the web, this would break: you couldn't do it. As Jim Gettys points out, as the era of digitally signed documents comes upon us, changing a signed document will break the signature on it. So allowing one to make a self-consistent document with internal links in a way independent of the namespace is even more essential.

This independence is very important for the evolution of the Web. It means that people can go off and design all kinds of new systems for naming, addressing and accessing documents, without having to worry about what sort of documents will be moved. It means that people can go off and make new media types (MIME types), each of which can have different concepts for views and fragments, without having to talk to the people developing the access technology. This has already (1998) proved incredibly enabling to the community, as HTTP has advanced in parallel with many other ways of accessing data, and the number of exciting media types has grown very rapidly, and will be the key to many new revolutions built on top of the basic Web idea.

If you look at the diagram you ill notice how the fragment IDs are generated by and understood by just the one module. You see how, when designing a new MIME type, one is quite free to be creative in making new and powerful forms of fragment ID, knowing hat no other specifications will refer to them, and nothing else will break.

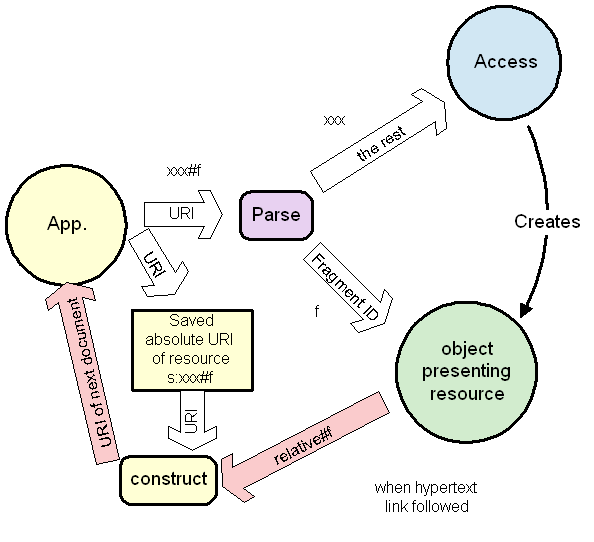

Now let us look at what happens when we follow a link. For example, say a hypertext page is clicked on. The page has a representation of the end point of the link. It hands it to the application. In fact, often, there are links between pages whose URIs are very similar and only differ in the right hand part. This isn't true of all name spaces: for example, when making links between news articles identifies by the news id (news:foo) unique ID, you have to specify the whole thing. However, if you restrict publication of a set of documents to a hierarchical name or address space, then you can arrange for documents which are very related and have many links to be in the same part of the tree.

In this case, the links between these documents are "relative URIs".

What happens then is that the relative URI, which only has the locally different part of the URI in it, is handed back to what in the diagram I have called the "application", to be turned into an absolute URI by being combined with the absolute URI of the resource, which the application has remembered.

Note that the application is aware of the absolute URI but still the resource does not have to.

Note that the fragment id is still circulated around a loop between the object (green) which understands it and the applications (yellow) which handles it transparently but does not understand or change it.

Now there was a design decision that the application could have passed to the access module both the relative URI and the absolute URI. Then, different namespaces would have been able to have different algorithms for resolving a base URI and a relative URI into a new absolute URI. But the decision was made that the relative address format should be common across all name spaces.

Just as we considered internal links above, now consider relative links between a bunch of documents, like the sections of a book, which are close in the tree. In practice, such document sets are moved from place to place, from file systems into HTTP space or FTP space, and because the relative address rules are universal, the documents do not have to be modified every time they are moved. (Yes, if you move half the set to one place and half to another, you have to fix links). This is happening all the time. People are creating and programs are generating hypertext with relative links without knowing or caring what absolute URI will be used to refer to the material.

The so-called "access scheme" is the first part of the URI. As we have seen above, you don't have to know anything about it to parse relative URIs or to process the fragment identifier of a URI. The knowledge of particular schemes is limited to the "access" function (blue in the above diagram).

The scheme is a very important flexibility point, and should not be abused. Anyone dereferencing a URI must have a knowledge of the scheme it uses.

The access scheme defines a huge part of URI space. The scheme defines a subspace with particular properties

The access scheme is by definition the highest point of flexibility. What does that mean? It means that if the whole Web develops problems which we cannot solve within the existing protocols, or if new spaces are designed which really can't be accessed through or mapped into existing spaces, then we can create a new space. We have faith that we will be able to use this flexibility point in the future, because it worked successfully for integrating the older spaces such as Gopher and FTP spaces into the Web.

| If you have ported a concept between environments in the past, then there is a better hope that you can in the future. |

However, we do not do this lightly. When we introduce a new space, it may have very different properties and we expect that the deployment of new software will be needed to allow access to it. Some spaces may be gatewayable into HTTP space, and this will often provide a transition path. This is why early browsers allowed one to declare in a configuration file what gateways to use for what new spaces.

If we use this extension point frivolously, ironically, it will cease to work. Suppose very many schemes are introduced. The access scheme space itself becomes a namespace with all the problems which current namespaces such as DNS are trying to solve, but which are very hard problems:

Worse, though, technology will be needed to automatically dereference the schemes themselves and download code to handle them. Something like DNS will be needed. The top level namespace then becomes in fact DNS, or something like it. This, however, begs the question. What happens if later DNS needs to be replaced? There is no top-level extension switch left. The world is stuck with whatever form of access-scheme name service exists.

Therefore, I conclude that access schemes should not be open to trivial extension, and that the access scheme should only be extended by the introduction of new standards with full open review by the entire community.

Whereas some schemes (like "data:") are clearly neat and new and orthogonal to HTTP, many schemes could in fact be integrated into http, using HTTP extension mechanisms.

In fact, is HTTP is to be taken as a general computing protocol, then use of an extensible language system for the HTTP request message would allow a huge amount of extension, covering protocols with different functionality (exporting different interfaces).

When considering the evolution of a space, it is important to remember that primarily the access scheme refers to a part of the URI space, and secondarily it refers to a protocol. Therefore, one can in fact change the protocols used to access resources within a scheme's namespace, without changing the space. For example, a new DNS protocol could be introduced which over time would replace the current one, without changing the DNS space. This would effectively redefine the HTTP and FTP protocols, but would not harm the namespaces. When touch-tone dialing was introduced, the telephone numbering system remained the same. So an indexing system could be introduced which, when deployed, would allow http:// space objects to be found with greater reliability or speed than the current protocols, while maintaining the HTTP space as being the concatenation of a DNS name and an opaque string.

The word "document" in the original "Universal Document Identifier" in the first web spec was changed to "Resource" in the IETF discussions, because (a) the word "document" didn't seem to cover all kinds of information resources such as movies and sounds, and (b) actually URIs exist for communication endpoints such as mailboxes (mailto:) and login ports (telnet:). "Resource" was, though, later used by RDF as a term for anything - the top class which is the superclass of all classes. This stemmed from RDF's initial use as a language for describing information resources on the Web, although RDF was designed to be used to describe anything as a general knowledge representation system. The term "Information Resource" was adopted by the TAG for the Web Architecture document. When people, including the author in the article above, refer to an information resource, they often

Content/Version negotiation and Fragment ID persistence: warnings and awareness. See Fragment Identifiers

If you negotiate between MIME types which have different fragment ID representations, you run a risk & should warn the client.

To be added:

Level breaking with care: optimizing in HTTPNG etc

Up to Design Issues, On to URIs