1 Preface

The names in a namespace form a collection. Sometimes it is a

collection of element names (DocBook and XHTML, for example),

sometimes it is a collection of attribute names (XLink, for example),

sometimes it is a collection of functions (XQuery 1.0 and XPath 2.0

Data Model), sometimes it is a collection of properties (FOAF),

sometimes it is a collection of concepts (WordNet). The names in a

namespace can, in theory at least, be defined to identify any thing or

any number of things.

Given the wide variety of things that can be identified, it follows

that an equally wide variety of ancillary resources may be relevant to

a namespace. A namespace may have documentation (specifications,

reference material, tutorials, etc., perhaps in several formats and

several languages), schemas (in any of several forms), stylesheets,

software libraries, applications, or any other kind of related

resource.

A user, encountering a namespace “in the wild” might want to find

any or all of these related resources. In the absence of any other

information, a logical place to look for these resources, or information

about them, is at the location of the namespace URI itself.

[WebArch Vol 1] says that it is a

Good

Practice for the owner of a namespace to make available at the

namespace URI “material

intended for people to read and material optimized for software agents

in order to meet the needs of those who will use the namespace”.

The question remains, how can we best provide both human and machine

readable information at the namespace URI such that we can achieve the

good practice identified by web architecture?

One early attempt was [rddl10]. RDDL 1.0 is an XLink-based

vocabulary for identifying the nature and purpose of related resources.

Several attempts were made to simplify RDDL. The TAG's original plan for

addressing

namespaceDocument-8

was to help define a simpler, standard RDDL format. However, time has passed,

RDDL 1.0 is now widely deployed. In addition, some of the proposed alternative

formats are also deployed. And it seems likely that over time new

variations may arise based on other evolving web standards.

This finding therefore attempts to address the problem by taking a step

back. We hope to:

Define a conceptual model for identifying related resources that is

simple enough to garner community consensus as a reasonable

abstraction for the problem.

Show how RDDL 1.0 is one possible concrete syntax for this model.

Show how other concrete syntaxes could be defined and identified in

a way that would preserve the model.

2 The Model

For the resource identified by a namespace URI, there may exist

other resources related to it. Borrowing on the terminology defined by

[rddl10], we say that each of these other resources has

a nature and a purpose. The nature of the resource is a

machine-readable label that identifies “what kind of thing” it is. For

example, its nature might be “HTML documentation” or “XML Schema” or

“CSS Stylesheet”. The purpose of a resource, with respect to the

resource identified by the namespace URI, is a machine-readable label

that identifies “what use” the thing is. For example, its purpose

might be “validation” or “normative reference” or “specification” or

“transformation”.

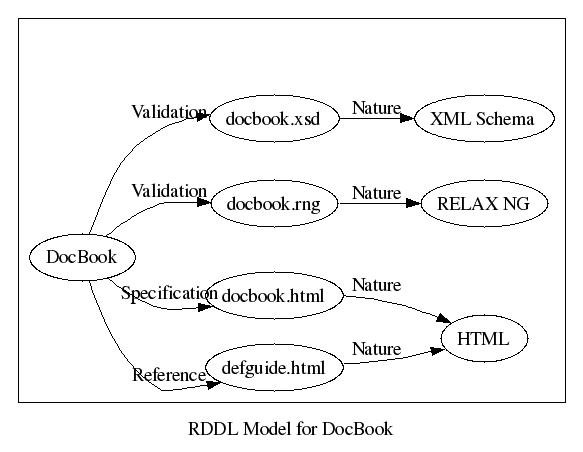

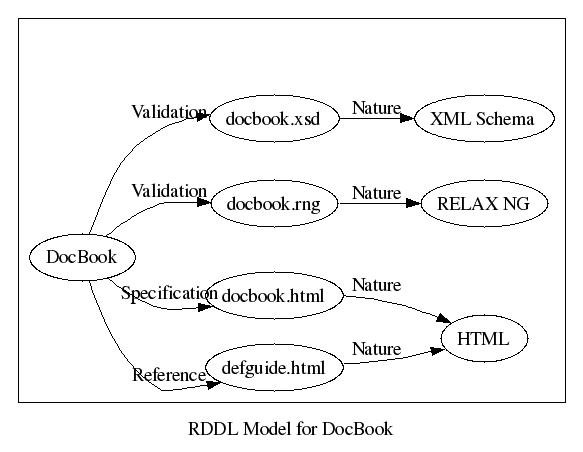

For example, here's a diagram of the model for some DocBook-related

resources:

This model indicates that for the purpose of validation there are two

schemas, docbook.xsd which has the nature “XML Schema” and

docbook.rng which ash the nature “RELAX NG”. This model

also includes two examples of HTML documentation, defguide.html

which has the purpose “reference documentation” and docbook.html

which has the purpose “specification”.

If an application can obtain this model from the document that it

gets from the namespace URI, then it can find the relevant related

resources. For example, a RELAX NG validator could find all the

resources that serve the purpose “validation” and identify the one (or

one of the ones) with the nature “RELAX NG” and proceed with a

validation task. Similarly, a human being could find the resource with

the purpose “specification” to locate the specification in a

convenient format.

One way to write down the model described above is with RDF. There's

nothing about the process of finding related resources that requires

the model to be instantiated in RDF or requires any processor to know

anything about RDF. But having the model in RDF will allow us to describe

how the model can be obtained from specific kinds of documents.

Here's an example of the DocBook model above, expressed in RDF using

N3:

# RDDL Model for DocBook

@prefix rddl: <http://www.w3.org/2005/11/rddl#> .

@prefix purpose: <http://www.w3.org/2005/11/rddl/purpose#> .

@prefix nature: <http://www.w3.org/2005/11/rddl/nature#> .

@prefix dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/> .

<http://docbook.org/ns/docbook>

purpose:validation <http://docbook.org/xml/5.0b1/rng/docbook.rng> ;

purpose:validation <http://docbook.org/xml/5.0b1/xsd/docbook.xsd> ;

purpose:spec <http://docbook.org/specs/wd-docbook-docbook-5.0b1.html> ;

purpose:reference <http://docbook.org/tdg5/en/html/> .

<http://docbook.org/xml/5.0b1/rng/docbook.rng>

rddl:nature nature:RELAXNG .

<http://docbook.org/xml/5.0b1/xsd/docbook.xsd>

rddl:nature nature:XMLSchema .

<http://docbook.org/specs/wd-docbook-docbook-5.0b1.html>

rddl:nature nature:HTML .

<http://docbook.org/tdg5/en/html/>

rddl:nature nature:HTML .

If we can construct this model from a namespace document, then we know

we have all the information we need to locate related resources.

3 RDDL 1.0

A RDDL 1.0 document encodes the nature and purpose of the related

resource in a rddl:resource element. That element uses XLink:

<rddl:resource xlink:title="RELAX NG for validation"

xlink:arcrole="http://www.w3.org/2005/11/rddl/purposes#validation"

xlink:role="http://www.w3.org/2005/11/rddl/natures/RELAXNG"

xlink:href="http://docbook.org/xml/5.0b1/rng/docbook.rng">

A <a href="http://docbook.org/xml/5.0b1/rng/docbook.rng">schema</a>

for RELAX NG validation.

</rddl:resource>

Extacting the model is a simple matter of reading the xlink:href,

xlink:role, and xlink:arcrole attributes of each

rddl:resource.

4 RDDL 2.0

One of the RDDL 2.0 proposals encodes the nature and purpose of the

related resource directly on the HTML a element:

A

<a rddl:nature="http://www.w3.org/2005/11/rddl/natures/RELAXNG"

rddl:purpose="http://www.w3.org/2005/11/rddl/purposes#validation"

href="http://docbook.org/xml/5.0b1/rng/docbook.rng">schema</a>

for RELAX NG validation.

Extacting the model is a simple matter of reading the rddl:nature,

rddl:purpose, and href attributes of each

HTML a.

5 Using GRDDL

A third approach is to use [GRDDL].

@@describe grddl@@

@@incorporate Dan's USPS example:

http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/usps

@@note that grddl doesn't actually require xslt except in the general case@@

@@note that the preceding examples use grddl too.@@

@@note that this technique would allow for non-human readable namespace

documents but that's counter to the spirit of the webarch good practice.@@

6 Natures

@@ list of natures, borrow from RDDL.

7 Purposes

@@ list of purposes, borrow from RDDL.