Abstract

This docuent is intended to compile and review

existing guidelines and articles to develop a preliminary analysis of the

needs of people who have accessibility needs related to ageing with regard to

accessing the Web.

Status of this document

This section describes the status of this document at the time of its

publication. Other documents may supersede this document.

This document is intended to provide a

background on the needs of the elderly with functional impairments accessing

the web. It will inform the modification of existing WAI documents and the

development of new WAI educational

and outreach materials.

This document is being reviewed by the Education and Outreach Working Group.

This current draft is nor endorsed by EOWG, but

is currently under review.

Please send comments about this document to wai-eo-editors@w3.org.

This is a draft document and may be updated, replaced or

obsoleted by other documents at any time. It is inappropriate to cite this

document as other than as work in progress.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The World Wide Web was invented in 1989 and the World Wide Web Consortium

was established in 1994 to lead the World Wide Web to its full potential. By

the turn of the century the Web had entered most aspects of our lives from

communication to eGovernment, eCommerce and eLearning, making it much more

than just an information repository. By the 2006 in addition to online

services (banking, taxation, shopping, etc) we also saw the advent of

web-based applications such as calendars, office-type applications, forums,

chat, etc. This evolving online world presents ongoing access challenges to

people with functional impairments and disabilities.

Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the Web and Director of the World Wide Web

Consortium (W3C), is regularly cited as saying “The power of the Web is in

its universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential

aspect” [TBL 1997] and more recently “One Web for

anyone, everywhere on anything” [TBL 2004] – this

is all part of the Web’s ‘full potential’. In 1999 the W3C Web

Accessibility Initiative (WAI) published the first set of international

guidelines for Web accessibility, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

(WCAG) 1.0, documenting the essential requirements for Web content to be

accessibility to people with disabilities. Accessibility requirements for

authoring tools (ATAG) and

user agents, including browsers, (UAAG) followed. At the time

of writing (early 2008) the W3C had advanced drafts available of WCAG 2.0 and ATAG 2.0 along with a specification

for Accessible Rich Internet Applications (WAI-ARIA) that will assist

scripted internet applications to become accessible.

Many countries in Europe and elsewhere have legislation in place to reduce

discrimination against people with disabilities, both young and old, along

with related policies or guidelines applying to online services [Policies].

The European Union and the European Commission (EC) has programmes in

place to ensure that eInclusion for people with disabilities is enhanced

among the Member States, and is also addressing the needs of the elderly and

other disadvantaged groups. In particular they have agreed to “Address the

needs of older workers and elderly people by … exploiting the full

potential of the internal market of ICT services and products for the

elderly, amongst others by addressing demand fragmentation by promoting

interoperability through standards and common specifications where

appropriate” (EC 2006). The EC has been addressing

the technology needs of the elderly for some time, however under the 6th

Framework Programme (FP6) of research under the Information Society and

Technology (IST) programme several calls have focussed on the needs of the

elderly in the information society (Placencia-Porrero,

2007).

This issue in compounding because the world’s population is living

longer with a disproportionate number of people soon to be elderly as

compared with any other period in human history. The United Nations estimates

that by 2050 one out of every five people will be over 60 years, and by 2150,

one third of the people in the world are expected to be 60 years of age or

older .

In Europe, as elsewhere, the population is also aging. European countries

in 1950 had a population of age 65+ of some 45 million; in 1995 the

population of age 65+ had already more than doubled to 101 million (approx.

15%); by 2050 Europe will have 173 million people age 65+ (20% of the

population).

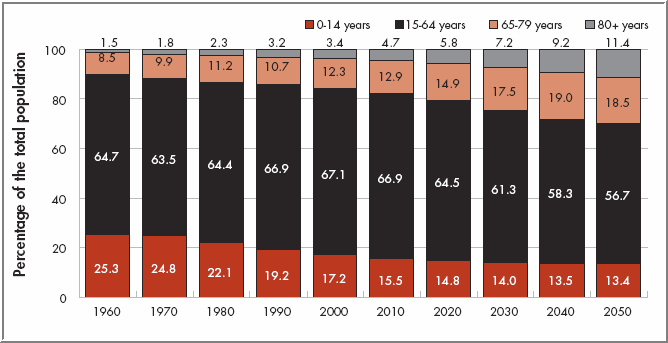

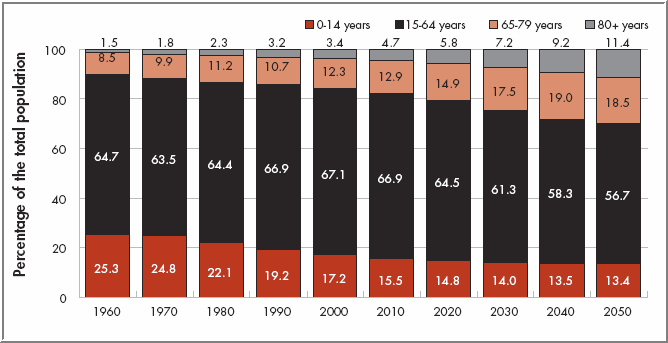

In the EU-25 countries, this means a change from 2000 when 15.7% of the

population was over 64, to an estimated 17.6% in 2010 and 20.7% in 2020

(Figure 1; Table 1). The trends by country are also interesting, and vary

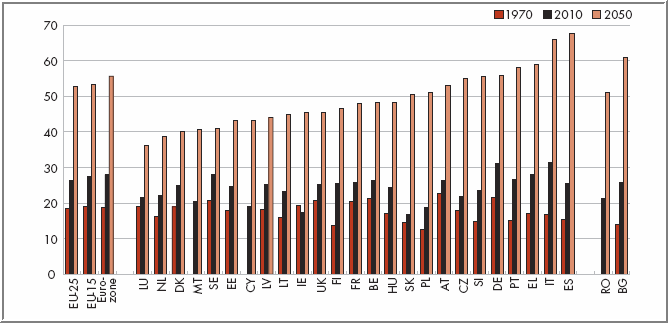

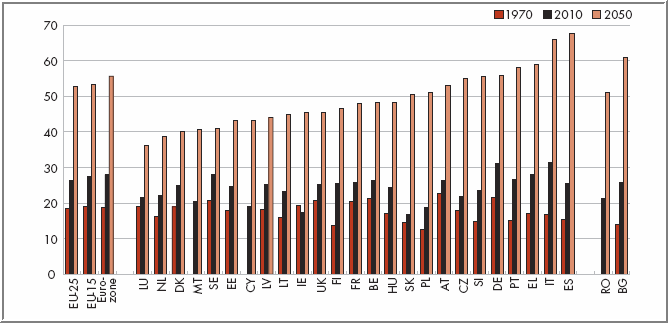

considerably (Figure 2). The EU-25 countries had a dependency ratio of

approximately 18 percent in 1970, but expected to rise to approximately 27%

by 2010 and 54 percent by 2050; across the EU the 2010 prediction ranges from

approx 17 percent in Slovakia to 32 percent in Italy.

This trend will put tremendous pressure on society in terms of supporting

the elderly population, and any means to assist them to continue contributing

to and participating in society, and to “age in place”, needs to be

adopted.

Figure 1 - Population structure by major age group for EU-25

countries (1960 to 2050 estimates)

see also Table 1 below (EC, 2007a)

Table 1: Population structure by major age groups: EU-25

for 1960 through 2050 by decade (EC, 2007a)

Age

|

1960

|

1970

|

1980

|

1990

|

2000

|

2010

|

2020

|

2030

|

2040

|

2050

|

80+ years

|

1.5%

|

1.8%

|

2.3%

|

3.2%

|

3.4%

|

4.7%

|

5.8%

|

7.2%

|

9.2%

|

11.4%

|

65-79 years

|

8.5%

|

9.9%

|

11.2%

|

10.7%

|

12.3%

|

12.9%

|

14.9%

|

17.5%

|

19.0%

|

18.5%

|

15-64 years

|

64.7%

|

63.5%

|

64.4%

|

66.9%

|

67.1%

|

66.9%

|

64.5%

|

61.3%

|

58.3%

|

56.7%

|

0-14 years

|

25.3%

|

24.8%

|

22.1%

|

19.2%

|

17.2%

|

15.5%

|

14.8%

|

14.0%

|

13.5%

|

13.4%

|

Figure 2 - Old age dependency ratio for EU-25 countries (1970 and

2010, 2050 estimates)

(population aged 65 and over as a percentage of the working age population

[15-64 years]) (EC, 2007a)

The European Commission has recognised this trend and need; with the

Information Society Technologies (IST), eInclusion is a strategic objective,

and for the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6) there is a specific objective to

include a focus on the needs of the ageing population (EC,

2004):

- To mainstream accessibility in consumer goods and services, including

public services through applied research and development of advance

technologies. This will help ensure equal access, independent living and

participation for all in the Information Society.

- To develop next generation assistive systems that empower persons with

(in particular cognitive -) disabilities and aging citizens to play a

full role in society, to increase their autonomy and to realize their

potential.

The WAI-AGE project addresses the objective for access to the Web, which

has become a ubiquitous resource and is one of the most widely used

technologies, and the foundation technology platform of today’s information

society.

The requirements of the elderly population for effective solutions for

“ageing in place” – continuing to work, participate in democracy,

undertake ecommerce, and live in one’s own home as abilities change later

in life – include the accessibility requirements for use of the Web to help

maintain independence, autonomy, and/or to help foster constructive

interdependence [ref??]. For instance, Web-based

telemedicine can help in maintaining health while living at home, however the

interface must accommodate elders who may have a range of potentially

disabling conditions, as well as potentially less prior experience with

information technologies, and thus more potential for technology phobias.

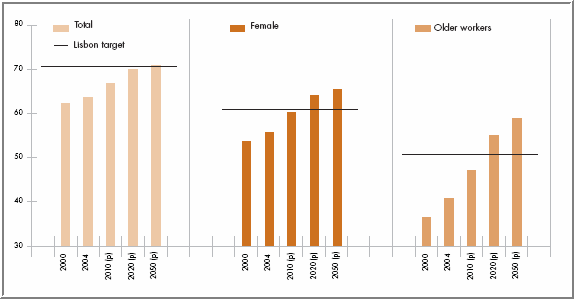

With the increase in the old age dependency ratios, many countries are

raising the retirement age or taking other actions to encourage a longer

working life. The EC expects the average working age to increase

significantly over the next decade as the population ages and suggest that

higher employment rates among older workers “need to be supported by

ensuring lifelong access to suitable training” (EC,

2007b). The EC projects employment rates for older workers to “increase

massively from 40% in 2004 for the EU-25 to 47% by 2010 and 59% in 2025”

(illustrated in Figure 3) marking a significant reversal of the long-term

trend towards earlier withdrawal from the labour force. Older workers have

accounted for three-quarters of all employment growth in the EU in recent

years (EC, 2007b).

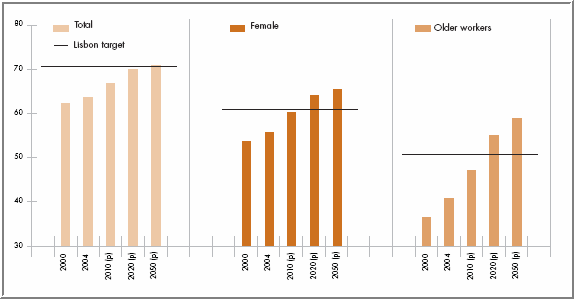

Figure 3 - Projected EU employment rates and Lisbon targets

(EC, 2007b)

To date there has been extensive development of guidelines for

accessibility of the Web for people with disabilities . However, while these

guidelines address many requirements needed by the ageing population, the

relevance of these guidelines to the needs of the elderly is not well

understood by organisations representing and/or serving the needs of the

ageing community [ref??], nor by technology

developers (Sloan, 2006). In addition, there may be

a need for extensions to WAI guidelines, techniques, or educational materials

to better address and/or promote the requirements that additionally benefit

people who experience a combination of changes in abilities due to ageing.

This review examines the literature relating to the use of the Web by

older people to primarily look for intersections and differences between the

WAI guidelines and recommendations for web design and development issues that

will improve the accessibility and usability for older people. It is intended

that the review will:

- better inform the ongoing work of W3C/WAI with regard to the needs of

the elderly and their web accessibility related needs

- inform the development of potential extensions on WAI guidelines and

techniques and/or provide direct input into “WAI 3.0” … ( the 3.0

version of WAI guidelines)

- lead to the development of:

- educational resources focused towards industry implementers

- educational resources focused towards organisations representing

and serving ageing communities

- help foster dialog between ageing communities and disability

communities around issues of web accessibility

- inform the contributions that W3C makes into the standards development

processes in Europe and internationally

2. Older adults and age-related functional limitations

2.1 Who is an older adult?

Are they 50+ or 65+?

Goldman Sachs, along with many others, have defined 60 as the new 55 in

terms of retirement from full-time work as life expectancy, health, and

economic expectations increase.

In the WHO document ‘Definition of an older or elderly person ’ (WHO,

undated A) it is suggested that “Most developed world countries have

accepted the chronological age of 65 years as a definition of 'elderly' or

older person”, but goes on to say “The UN has not adopted a standard

criterion, but generally use 60+ years to refer to the older population”

(e.g. WHO, Undated B ‘Ageing’).

The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) study of 2004 (Redish

and Chisnell, 2004) found that previous studies (2000 - 2004) of the elderly

and their use of the Web or ICT used a variety of definitions, from 50+ years

through to 65+ years. Bailey (2004) reviewed a number of studies and journals

and proposed:

- Young: 18-39 years

- Middle-aged: 40-59 years

- Older: 60-74 years

- Old-old: 75+ years

The AARP itself considers ‘older adults’ to be those over 50 years,

while many western countries (including the USA) consider the retirement age

to be 65 years.

However, in addition to chronological age defining ‘elderly’, we need

to account for the diversity in ability resulting from the development of

functional limitations associated with ageing, and also the diversity of

attitude and aptitude, when we are discussing the use of technology,

especially ICT and the Web.

2.2 How older adults use the Web

All the evidence from the studies that report about the online activities

of the elderly suggest that they do the same as most other age groups –

that is communication and information searches as well as using online

services. Kantner & Rosenbaum (2003) observe, that “email and children

were primary reasons” why many seniors started to learn using computers;

Morris, Goodman and Brading (2007) also found that email and communication

was an important factor in the elderly being online.

Fox (2004) found that that older USA Web users do product research (66%),

purchases goods (47%), make travel reservations (41%), visit government Web

sites (100%), look up religious and spiritual information (26%) and do online

banking (20%). Morris, Goodman and Brading (2007), in their UK (Derbyshire)

study, found that the information searches were often related to hobbies and

interests (68%), travel and holidays (50%) and health or medical (28%). Dinet

et al. (2007) found from a study of older French users (age 68 – 73 years)

that health was the most looked for topic online, the second was recreation

and travel and the third most popular was services.

Wired seniors are often as enthusiastic as younger users in the major

activities that define online life such as email and the use of search

engines to answer a specific question (Fox, 2004). In other words, we should

not stereotype all older adults as technophobes. Weinschenk (2006), citing

Human Factors International’s experience along with other research

(O’Hara, 2004), warns designers against stereotyping the elderly as

non-computer, non-internet, users.

Several studies even report that the elderly use the Web for romantic

interests (e.g. Malta, 2007) and the Wall Street Journal in 2004 was warning

Web site designers that overlooking older adults was “an oversight that can

be costly to businesses online as the population ages and as more seniors

discover the Internet”.

Morris, Goodman and Brading (2007) concluded that the Internet “does

enhance the lives of older people” even if the older elderly use the

internet less than younger elderly groups.

Other areas of importance?

- Leisure – including libraries (Mates, 2003)

- Why the elderly may not be online?

Also discuss the potential difference between current groups who often

have no prior ICT experience and future groups (eg baby-boomers) who will

often have prior ICT experience …

2.2.1 How many older users are online?

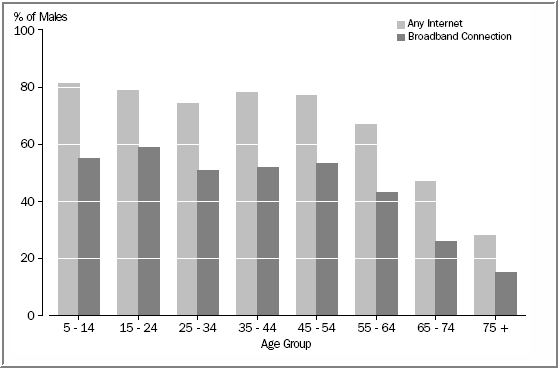

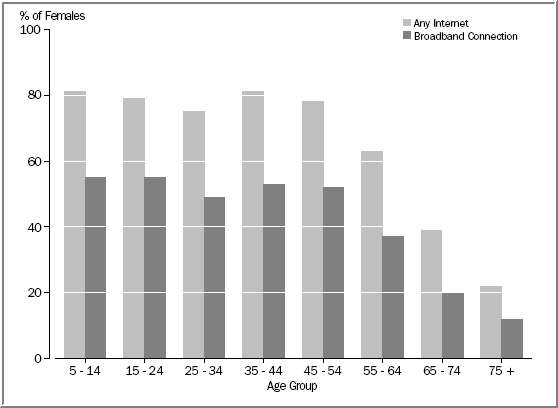

Internet access in 2006 in Australia by people living in occupied private

dwellings was analysed by age group. The Australia Bureau of Statistics found

that people with ages between 5 and 14 have the highest proportion of access,

followed by people in the 15-24 age range. They found the proportion tapers

off sharply for people over 55 years, with only a quarter of people 75 years

or above having access to the Internet in 2006 as shown in Figure 4 (ABS,

2007).

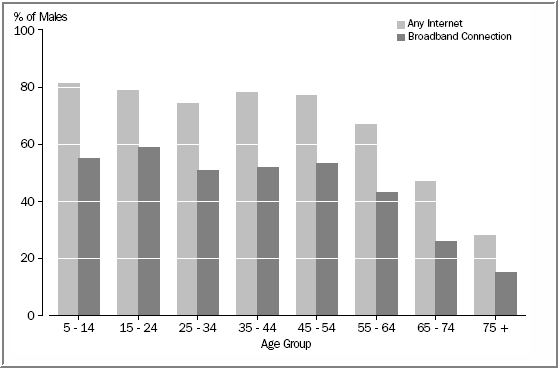

Figure 4a - Internet access by age group in 2006 for Australian

males (ABS, 2007)

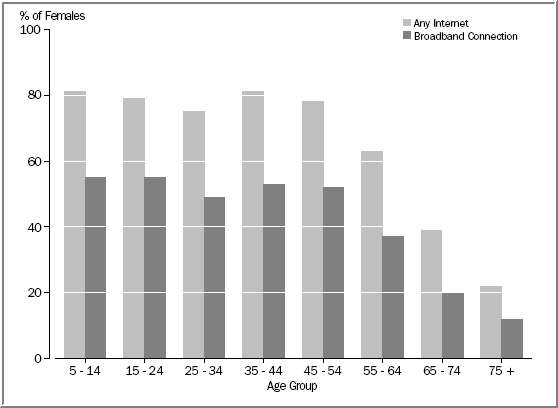

Figure 4b - Internet access by age group in 2006 for Australian

females (ABS, 2007)

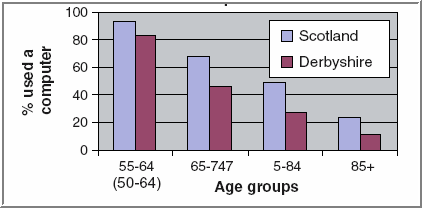

In the UK a 2004 survey (Morris, Goodman and Brading, 2007) showed that

approximately one-third of older people (over 55 years) had used the internet

at some point in their lives with use dropping with age. The Office of

National Staistics in the UK showed that by 2006 that figured was increasing

(Table X).

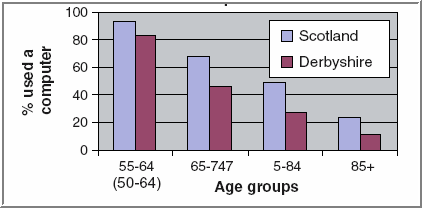

Figure 5 - Internet use at any point in their lives

(survey from Scotland and Derbyshire UK, 2004)

Table X: UK Adult internet usage (Office National

Statistics UK, 2006)

|

Age Group

|

Within the last 3 month

|

Between 3 months

and 1 year ago

|

More than 1 year ago

|

Never used it

|

|

16-24 years

|

83%

|

4%

|

3%

|

10%

|

|

25-44 years

|

79%

|

3%

|

2%

|

17%

|

|

45-54 years

|

68%

|

4%

|

2%

|

26%

|

|

55-64 years

|

52%

|

3%

|

2%

|

43%

|

|

75+ years

|

15%

|

1%

|

2%

|

82%

|

In Spain, a 2007 survey by the National Statistics Institute reported that

percentage of older people using computers and the internet dropped very

sharply for 65-74 years old people compared with 55-64 year olds (Table

2).

Table 2 – Spanish Survey on Use of Information and

Communication Technologies in Households (Instituto Nacional de

Estadística, 2007)

Age

groups

|

used a computer in the last 3

month

|

used the Internet in the last 3

months

|

used the Internet at least once a

week in the last 3 months

|

made a purchase over the Internet in

the last 3 months

|

16 to 24 years

|

89.3%

|

86.3%

|

76.9%

|

16.5%

|

25 to 34 years

|

78.0%

|

72.6%

|

61.3%

|

21.0%

|

35 to 44 years

|

64.9%

|

57.1%

|

47.8%

|

15.1%

|

45 to 54 years

|

52.1%

|

45.9%

|

38.4%

|

11.6%

|

55 to 64 years

|

25.7%

|

21.1%

|

18.3%

|

4.4%

|

65 to 74 years

|

7.5%

|

6.4%

|

5.2%

|

1.3%

|

Total

Personas

|

57.2%

|

52.0%

|

44.4%

|

13%

|

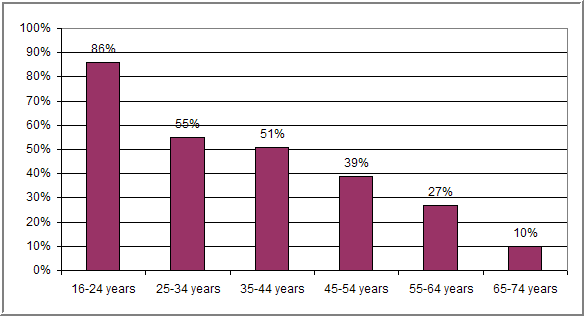

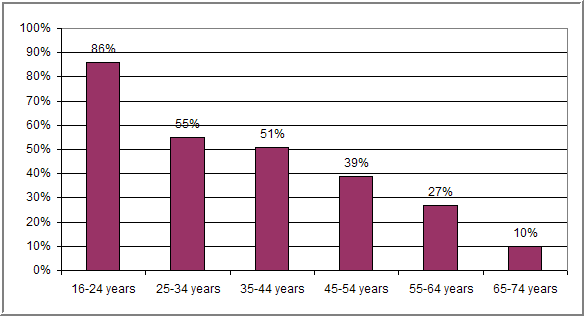

Figure 5 - EU Internet Use by age in 2005

(Eurostat, Community survey on ICT usage in households and by individuals,

2005)

Table 3 - EU Internet Use by age in 2005

(Eurostat, Community survey on ICT usage in households and by individuals,

2005)

Age Group

|

Internet use

at least once per week

|

16-24 years

|

86%

|

25-34 years

|

55%

|

35-44 years

|

51%

|

45-54 years

|

39%

|

55-64 years

|

27%

|

65-74 years

|

10%

|

Some indicators are also available from the USA:

“In a February 2004 survey, 22% of Americans age 65 or older reported

having access to the Internet, up from 15% in 2000. … By contrast, 58% of

Americans age 50-64, 75% of 30-49 year-olds, and 77% of 18-29 year-olds

currently go online.” (Fox, 2004)

2.3 What are age-related functional limitations?

The commonly accepted limitations that often arise during the normal

ageing process are:

- Vision decline

- Hearing loss

- Motor skill diminishment

- Cognition effects

The ageing process can often result in elderly people experiencing

multiple functional limitations.

2.3.1 Vision decline with ageing

Lighthouse International , Agelight and Salvi, Akhtar and Currie (2006)

give excellent descriptions of many of the declining vision conditions that

most older adults naturally experience, from the yellowing of the eye’s

lens and presbyopia (loss of elasticity of the lens) to pupil shrinkage.

These conditions result in a variety of vision changes:

- Decreasing ability to focus on near tasks, including a computer screen

- Colour perception and sensitivity; less violet light is registered,

making it easier to see red and yellows than blues and greens and often

making darker blues and black indistinguishable

- Pupil shrinkage; resulting in the need for more light and a diminished

capacity to adjust to changing light levels. For example, 60 year old

retinas receive only 40% of the light that 20 year retinas receive while

80 year old retinas only receive around 15%

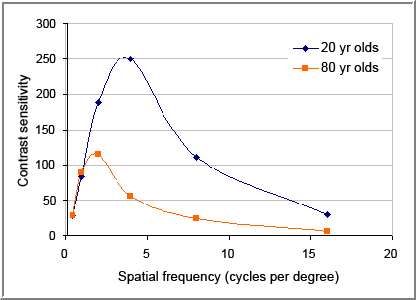

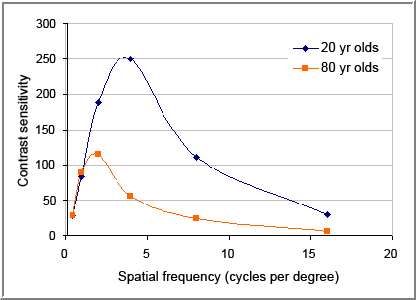

- Contrast sensitivity; from the age of 40, contrast sensitivity at

higher spatial frequencies starts to decline until at the age of 80 it

has been reduced by up to 83% (See Figure 6)

- Reduction in visual field

Figure 6 - Contrast sensitivity decreases dramatically with age

for all but low spatial frequencies (EveryEye, 2004)

The RNIB has estimates of eyesight decline in the older population in the

UK for people whose sight significantly affects their daily life:

- 15.8% aged 65 to 74 years

- 18.7% for ages 75 – 84 years

- 45.8% for ages 85+ years

In addition to the natural ageing of the eye, two common eye diseases of

the elderly can also seriously affect vision:

- Cataracts , which is a clouding of the clear lens in the eye resulting

in blurred vision and glare sensitivity. This is treatable in it’s

early stages.

- Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD), resulting in central vision

deterioration and an inability to see fine detail and distinguish colour

possibly combined with a sensitivity to glare. AMD is not reversible.

Table 4 - Causes of sight problems in older

people (RNIB, 2008)

Cause

|

Percentage of population

(for binocular VA <6/18)

|

Age-related Macular

Degeneration (AMD)

|

36.2%

|

Refractive error

|

31.6%

|

Cataract

|

24.5%

|

Glaucoma

|

7.9%

|

Myopic degeneration

|

2.9%

|

Diabetic eye disease

|

2.3%

|

2.3.2 Hearing loss with age

The majority of people who have a hearing loss are older people; they

usually notice a gradual age-related reduction and the increasing inability

to hear high-pitched sounds (Hearing Concern, 200x) . The Royal National

Institute for Deaf People (RNID) estimates for the UK that at around the age

of 50 the proportion of deaf people begins to increase sharply and 55% of

people over 60 are deaf or hard of hearing.

Table 5 - Estimated percentages of the UK population who

are deaf or hard of hearing (RNID, 200x)

|

16 to 60 years

|

61 to 80 years

|

Over 81 years

|

All degrees of deafness

|

6.6%

|

46.9%

|

93.2%

|

|

|

4.6%

|

28.1%

|

18.4%

|

|

|

1.6%

|

16.5%

|

57.9%

|

|

|

0.2%

|

1.9%

|

13.2%

|

|

|

0.1%

|

0.4%

|

3.6%

|

2.3.3 Motor skill diminishment

Arthritis is a major cause of mobility issues for the elderly and

Wikipedia reports that arthritis is the leading cause of disability in people

older than fifty-five years. The US-based Arthritis Foundation reports that

50% of Americans over 65 experience arthritis (Arthritis Foundation, 2008) ,

while Arthritis Care in the UK report that 20% of all adults in the UK are

affected (Arthritis Care, 2007).

Another age-related condition is Parkinson's Disease, a progressive

neurological condition affecting movements such as walking, talking, and

writing. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in the

US reports that the four primary symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease are

(NINDS, 2008):

- Tremor – trembling in the hands, arms, legs, jaw and face

- Rigidity – stiffness of he limbs and trunk

- Bradykinesia – slowness of movement

- Postural instability – impaired balance and coordination

The Parkinson’s Disease Society in the UK states “The risk of

developing Parkinson's increases with age, and symptoms often appear after

the age of 50. Some people may not be diagnosed until they are in their 70s

or 80s.” Wikipedia reports that Parkinson’s Disease can also lead to

cognitive and visual disturbances .

Both arthritis and Parkinson’s are likely to cause difficulties with the

mouse use, and even other pointing devices, as well as keyboard use for some

sufferers.

2.3.4 Cognitive decline with age

Wikipedia’s entry on Aging and Memory talks about memory decline in the

normal ageing process and states:

“The ability to encode new memories of events or facts and working memory

shows decline in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Hedden

& Gabrieli, 2004 ). Studies comparing the effects of aging on episodic

memory, semantic memory, short-term memory and priming find that episodic

memory is especially impaired in normal aging (Nilsson, 2003 ). These

deficits may be related to impairments seen in the ability to refresh

recently processed information (Johnson et al., 2002 ). In addition, even

when equated in memory for a particular item or fact, older adults tend to

be worse at remembering the source of their information (Johnson,

Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993 ), a deficit that may be related to

declines in the ability to bind information together in memory (Mitchell et

al., 2000 ).”

It has also been suggested (Caserta and Abrams, 2007) that situation

awareness may be relevant to cognitive aging, affecting older adults’

perception and comprehension of their environment.

Cognitive deficits come in many forms as discussed earlier, but among the

elderly, dementia, including Alzheimer’s Disease appears to be the most

prevalent. Alzheimer’s Disease International provides figures showing that

the incidence of dementia is nearly 25% among over 85 years olds (Table 6).

Alzheimer Europe (2005) estimate that between 1.14% and 1.27% of citizens

over the age of 30 years in the European Union are living with a form of

dementia.

Table 6 - Prevalence rate of dementia with age

(Alzheimer’s Disease International, 1999)

Age group

|

Rate

|

65-69 years

|

1.4%

|

70-74 years

|

2.8%

|

75-79 years

|

5.6%

|

80-84 years

|

11.1%

|

85+ years

|

23.6%

|

Alzheimer’s organisations suggest that dementia is progressive and that

during the course of the disease the chemistry and structure of the brain

changes, leading to the death of brain cells (Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2003)

They also suggest that people with multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease,

Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease may also be more likely to

develop dementia. Symptoms are identified as including:

- Loss of memory

- Confusion and problems with speech and understanding

- Mood changes

- Communication problems.

The Alzheimer’s Forum in the UK publishes tips for coping, including

computer tips which include the suggestion of getting a mouse that works

properly for the users and adjusting the mouse pointer to suit to suit the

user (http://tinyurl.com/5e2kxn).

Distractibility … need to discuss following articles:

- Fabiani et al, 2006

- Grady et al, 2006

Many older adults may not suffer from Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease,

but do suffer Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or subjective memory loss (UCSF

; Alzheimer’s Australia, 2006). The complaints associated with MCI

include:

- trouble remembering the names of people they met recently

- trouble remembering the flow of a conversation

- an increased tendency to misplace things

All these complaints are likely to also impact on the use of many Web

sites. Other forms of cognitive diminishment that may arise with ageing –

the effects of stroke can result in conditions similar to intellectual

impairment.

2.3.5 Multiple sensory loss and function

impairments

Brennan, Horowitz and Ya-ping (2005) report that twenty percent of

America’s older adults (over 70 years) reported dual sensory impairment and

the high levels of dual impairment were shown to increase the risk of

difficulty with the ‘instrumental activities of daily living’ (including

using a telephone, and hence probably a computer and the Web). Brennan,

Horowitz and Ya-ping’s findings highlight the importance of sensory

resources for everyday competence and the elderly maintaining their

functional independence.

2.4 Attitude and Aptitude

Many authors observed that not all older adults are the same, and that

attitude and aptitude can vary significantly across the elderly age group

(e.g. Coyne and Nielsen, 2002; Gregor et al., 2002; Redish and Chisnel, 2004;

Scott, 1999). Ability is often related to experience, for example mouse

control for elderly new computer users can be problematic (Dickinson et al,

2005; Hawthorn, 2005).

Morris, Goodman and Brading (2007) found that “the barrier is not age,

but the respondents’ idea that older people cannot or do not use

computers”. Additionally, many of the survey respondents in their UK study

cited a lack of Internet access as a key barrier to use.

However, as Morrell (2005) suggests, the post-WWII “baby boomers”, who

are moving into the category of ‘older adult’, have often been using ICT

at work, and will have greater ability than many current retirees who don’t

have a history of experience with ICT and may have begun by using the Web for

the first time in the 1990’s and early 2000’s.

2.5 User requirements for an elderly Web user

To be written ...

3. A Review of the Literature

Many studies have been undertaken of the use of the web by older people,

some research based, some user observation, some surveys, some expert

opinion. Some of these studies have looked at the elderly as a group, others

have focused on specific issued faced by the elderly, including their

approach to learning about ICT and the Web. Some of the studies have

referenced the work of the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), but many

seem to have been undertaken in oblivion of this work and the WAI Guidelines

which were first released in 1999.

Many of the studies discovered (see Appendix) identify the sensory

impairments that develop with age such as vision, dexterity, and hearing as

important, while others identify the issue of cognitive ability and overload

as key to some elders’ ability to use Web technologies. A compounding issue

is that people with accessibility needs due to ageing are less likely to

identify themselves as “disabled” than people who experience these

changes earlier in life (e.g. Bjørneby, 1999). As a result, they are less

likely to learn of, and to avail themselves of, resources which can help

address their needs. The studies listed in the Appendix can be classified in

many different ways by the methods used or approaches taken, in their

investigations, for example:

- Methodology focus – Observation of users, often around case studies;

Surveys; Focus groups, but not task oriented; Expert opinion, sometimes

based on a review of previous work

- Disability or impairment focus – Physical/mobility; Cognition;

Vision; Pan-disability

- Web aspect studied – Searching; Forms completion; Shopping;

eLearning; Web use training; eHealth access

- Web Design aspects – Involving the elderly in the design process;

Site architecture

Of course, there are always studies that do not fall into these

categories.

There is also the cross-over between Accessibility and Usability to

consider; for this review accessibility is taken to include the Guidelines

and Success Criteria from WCAG 2.0 that address the needs of people with

disabilities using the Web, along with those parts of ATAG and UAAG that

affect Web usage and participation. A consideration of the cross-overs may

lead to more useful outcomes/recommendations for future WAI work.

A majority of the articles discovered (see Appendix) originated from

Europe, but a significant number also originated from North America, with a

few from Asia and Australasia.

3.1 Existing literature reviews

Most of the scientific papers identified in the Appendix included

literature reviews relevant to their particular topics, but a few papers were

primarily reviews of previous literature.

Redish and Chisnell (2004) reviewed a large number of articles, books,

presentations, Web sites and papers published between 2000 and 2004 relating

to web design for older adults. They were looking for broad usability issues

for older Web users, while this review aims to identify opportunities to

extend the existing WAI technical, education, and outreach work to

accommodate the overlapping needs of people with disabilities and older

adults with age-related functional limitations. Redish and Chisnell were not

surprised to find that much of what they found in the literature about older

adults on the Web is good usable design for everyone – consistent

navigation, clear writing, skim-able text with lists, etc. Another aspect of

the elderly that their study reinforced is that older adults are not a

homogenous group – something that many others have also commented on (e.g.

Gregor et al., 2002; Fox, 2004; Morrell, 2005).

Redish and Chisnell commented that older adults are actually less

homogenous as an age-group than younger adults. Redish and Chisnell grouped

their findings into four aspects of design – interaction, information

architecture, visual design, and information design. Some of the issues they

highlighted include:

- Interaction design:

- Design convention such as underlined links should be followed

- Scrolling and other mouse activities are a learned behaviour and

becomes more difficult with age making pull-down menus, scrolling

lists, and scrolling pages difficult for some users

- Understanding, and accessing, what is clickable can be problematic

for some elderly users

- Feedback in multiple modes (visual and auditory) may be beneficial

- Information architecture:

- Clear labelling (of links, headings and menu items) seems to be

more important for older users than younger users

- Breath vs. depth - shallow information hierarchies seemed to work

better for older users

- Redundant links – the studies they reviewed leant both ways

- Visual design:

- Experienced older users can scan pages as well as younger users,

but newer elderly users can find busy pages and pages with irrelevant

material (such as adverts) distracting

- Older users generally prefer larger text – naturally

- Older adults with vision deficits need to be accommodated with

suitable contrast along with headings to help them narrow their

visual search

- Information design:

- Skimming and scanning is common across all age groups and vision

abilities

- Content development, plain language and ‘writing for the web’

are critical

Redish and Chisnell conclude by suggesting that older adults should be

included more in usability studies of Web design.

Other papers to discuss:

- Paul and Stegbauer (2005)

3.2 Previous approaches to ‘senior friendly’ Web

guidelines

Many investigations this decade have developed or compiled usability

guidelines for making Web sites “senior friendly”, in addition to the Web

Content Accessibility Guidelines from W3C for people with disabilities. As

Zaphiris, Kurniawan and Ghiawadwala (2006) suggest, some of these are

developed in academia and are theory driven, while others come from the Web

industry and are derived from practical experience. A selection of these

guidelines published since the release of WCAG 1.0 include:

- SPRY (1999) - A Guide for Web Site Creators

(not discussed as released the same year as WCAG 1.0)

- Holt (2000) - Creating senior-friendly web sites

- Agelight (2001) – Interface design guidelines for users of all ages

- NIH/NLM (2002) – Making your Web site senior friendly – A checklist

- Coyne and Nielsen (2002) – Web usability for senior citizens

- AARP (2004) – Designing Web sites for older adults: heuristics

- Kurniawan and Zaphiris (2005) – Research-Derived Web Design

Guidelines for Older People

- Fidgeon (2006) – Usability for older Web users

Morrell (2005) in writing up the experience of compiling guidelines for a

site to be used by older adults (www.nihseniorhealth.gov) found adequate

systematic and descriptive research to facilitate this, but expressed dismay

over the duplication of research by recent studies. This confirms the general

feeling that this author has had, that many studies are either “reinventing

the wheel” or not surveying and building on the appropriate range of

existing literature. Other studies seem to repeat the mistakes of others in

their recommendations, e.g. recommending against double-clicking.

3.2.1 Holt’s guidelines (2000)

Holt (2000) created one of the earliest set of guidelines for

senior-friendly Web sites where she focussed on addressing some of the

functional declines often experienced with ageing. This early checklist

contained four groups of recommendations:

- Design – background and contrast; font choice and text size; colour

choice including links; left justification; spacing and white-space;

avoid auto-scrolling

- Layout – short pages; consistent layout; simplicity of design; avoid

pull-down menus; avoid frames; clear branding across the site; clear

navigation with icons and distinct text links

- Content – clear page organisation; appropriate language; illustrated

instructions

- Multimedia – clear graphics with alt-text; minimal animation; careful

use of audio

While the basis of these Holt’s checklist was not clear, much of

Holt’s discussion reflected the Checkpoints from WCAG 1.0, while some of it

addressed real issues many functionally limited older adults will experience

such as difficulty with pull-down menus and auto-scrolling text.

3.2.2 Agelight’s guidelines (2001)

In 2001, the agelight organisation, in consideration of the ageing

population and the functional limitations often faced by them, published a

set of guidelines to help Web designers accommodate the natural changes in

ability often associated with ageing. These guidelines, described as

“interface design guidelines for all ages”, centred around six aspects of

page design:

- Layout and style:

- Animation and graphic elements – avoid flashing and blinking;

minimise pop-ups and ad-banners; don’t clutter pages with icons and

design elements

- Avoid distracting background elements – use a light fill colour

instead

- Balance of type and open space – cleaner pages are easier to read

and navigate; include section links for long pages

- Design for Internet appliances – e.g. WebTV and mobile

devices

- Hand eye coordination – clicking and scrolling can be difficult,

so ensure he targets are large and static

- Hard coding – allow a use to customise the page content and the

navigation areas for preferred fonts, text size and colours

- Links – ensure they are underlined, identifiable and descriptive

(do not underline other text)

- Page length – use judgement, but be aware of download times

- Navigation bars and links – consistency is important; redundancy

is useful

- Paragraph alignment – use left-alignment

- Style sheets – design and apply consistent style sheets across

the site

- Colour:

- Colour spectrum – use complementary colours from the colour

wheel; avoid adjacent colours

- Colours to avoid – take care, use bright colours and avoid

fluorescent colours and very pale colours ; do not use colour alone

to indicate or refer to information

- Contrast – use dark text on light or white backgrounds

- Text:

- Legibility – keep it basic to keep it readable

- Size – 12-14 points (many users do not know how to make changes

in the browser); allow users to change the size o Typefaces – sans

serif fonts may be best for screen reading

- Type weight – limit bold for adding emphasis

- Kerning & leading – don’t tighten it

- Use of all capitals – avoid as it is harder to read

- General usability and testing:

- Test the pages – on different monitors and resolutions

- Connectivity and modem speed – offer different version of

documents and videos to suit peoples bandwidth

- Date stamping – date stamped pages increase confidence in the

material

- Alt-tags – add concise descriptive alt attributes for all images

- Archive old articles o Search capability – important as a site

grows; offer Boolean searching as well

- About Us – add background and contact information to increase

confidence in the site

- Error messages – avoid “page not found” errors

- External links opening in new windows – discussed, but no

recommendation

- Page size and download speed – check it and keep it

‘reasonable’

- Tables and Frames – make sure the site works without frames;

provide a text-only version of table-based information

- Proprietary tags and scripting – make sure they are not relied

upon

- Language, reading level and terminology – if you are repurposing

content from another use, consider rewriting it for the online

audience

- Accessibility and Disability:

- Accommodating people with disabilities and their assistive

technologies is likened to curb-cuts for wheel chairs and the broader

benefits to mothers with strollers, delivery men, and cyclists

- User customisation

- Addressing the end users, suggestions are made about selecting or

upgrading hardware such as the mouse, and customising the browser

Many of the recommendation are common-sense usability issues, while others

address some of the specific needs of the elderly facing various functional

limitations. As many of these recommendations overlap with WCAG 1.0, it was

good to see the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative listed in the additional

resources for this paper.

3.2.3 National Institute of Aging’s guidelines

(2002)

NIA/NHM (2002) prepared a checklist for making sites ‘senior friendly’

compiled from a variety of previous research findings. This checklist

includes five groups of recommendations:

- Designing readable text for older adults:

- Use a sans serif typeface

- Use 12 or 14 point body text

- Use a medium of bold face type

- Use ‘normal’ case for most text, avoiding all capitals and

italics; use underlining for links only

- Double space all body text

- Left justify all text

- Avoid yellow and blue and green together

- Use dark text or graphics on a light background (or white on dark);

avoid patterned backgrounds

- Presenting information to older adults:

- Present information in a clear and familiar way; use positive

sentences

- Use the active voice

- Write in a simple language; provide a glossary for technical terms

- Organise the content in a standard format

- Incorporating other media:

- Use text-relevant images only

- If using animation, video or audio, keep the segments short to

reduce download time

- Provide text alternatives such as transcripts or open captioning

for all animation, video and audio

- Increasing the ease of navigation:

- The organisation of the site should provide for simple and

straightforward navigation; carefully label links

- Use single mouse clicks to access information

- Use a standard page design and consistent layout

- Incorporate text with icons; use large buttons

- Use pull-down menus sparingly

- Avoid automatically scrolling text

- Incorporate “previous” and “next” buttons to aid navigation

- Provide a site map to explain the site organisation

- Use icons with text as hyperlinks

- Provide email and phone contact information

- Final check:

- Establish some focus groups and/or undertake some usability testing

to evaluate the accessibility and friendliness of the site

Some of the NIA/NHM checklist items are targeted at overcoming the

functional limitations experienced by many elderly users, while others

address a potential lack of familiarity with the browsers and the Web. Some

of the NIA/NLM checkpoints duplicate WCAG 1.0 checkpoints (e.g. provide

alternatives for multimedia and provide a consistent layout), while others

could be seen to conflict (e.g. use 12 or 14 point text).

Morrell (2005) provides a description of the development of the Checklist,

and its application to the development of the www.nihseniorhealth.gov Web

site providing information on health topics applicable to older adults. The

usability testing of the NIHseniorhealth Web site and other sites following

the Checklist has confirmed their usefulness in making sites senior-friendly.

3.2.4 Coyne and Nielsen’s guidelines (2002)

Coyne and Nielsen (2002) could be considered to have prepared the first

definitive set of senior-friendly Web site design recommendations based on

user observation published as “Web Usability for Senior Citizens”. Their

study of 40 (experienced) users over 65 years derived 65 guidelines in 6

groupings for Web site designs that would better accommodate older users:

- Presenting information and text:

- text size ≥ 12pt; provide button for text-size adjustment; make

information scanable; use clear writing; limit scrolling;

- Presenting navigational elements and links

- differentiate links and headings; avoid movement; provide clear

links; link text size ≥ 12pt (with clickable border); ensure good

contrast (& changed after visit); provide clear link text; ensure

the usability of drop-down menus

- Search

- accept punctuation (including dashes/hyphens); repeat search terms

with results; provide clear search help; precisely label the search

field; ensure results are not hidden off-screen

- Presenting items for sale

- pictures (clear ones) are good; provide clear category headings;

shopping cart usability

- Forms

- accept dashes/hyphens in Credit Card numbers Phone numbers; be very

careful with dates; give clear error messages and accept good data;

- Web address and homepage

- register grammatical variations of your URL; have a ‘true’

clear home link on each page;

Additional usability issues relating to the browser and operating system

were discussed, including the issues of users confusing the address field

with the site’s search field as also observed by Kantner and Rosenbaum

(2003).

Like the previous guidelines, Coyne and Nielsen’s guidelines address

issues of functional impairment along with broader useability issues that

will benefit everyone such as their Search recommendations.

3.2.5 AARP’s guidelines (2004)

AARP (2004) from the investigation and review by Redish and Chisnell

(2004) published a set of heuristics (issues) for the evaluation of web site

design for older adults:

- Interaction design: designing the way users interact with the site

- Use conventional interaction elements

- Make it obvious what is clickable and what is not

- Make clickable items easy to target and hit

- Minimize vertical scrolling; eliminate horizontal scrolling

- Ensure the ‘back’ button behaves predictably

- Let the user stay in control o Is there clear feedback on actions?

- Provide feedback in other modes in addition to visual

- Information architecture: organising the content

- Make the structure of the Web site as visible as possible

- Clearly label content categories; assist recognition and retrieval

rather than recall

- Implement the shallowest possible information hierarchy

- Include a site map and link to it from every page

- Visual design: designing the pages

- Make pages easy to skim or scan

- Make elements on the page easy to read

- Visually group related topics

- Make sure text and background colours contrast

- Use adequate white space

- Information design: writing and formatting he content

- Make it easy to find things on the page quickly

- Focus the writing on audience and purpose

- Use the users’ language; minimize jargon and technical terms

The majority of the AARP’s heuristics might just be considered

conventional usability wisdom – most of this list is of benefit to all

users, not just elderly users or users with functional limitations.

3.2.6 Kurniawan and Zaphiris’ guidelines (2005)

Kurniawan and Zaphiris (2005) and their colleagues reviewed much previous

literature in the area of HCI and ageing to derive an initial set of 52

guidelines. These were then categorised by forty postgraduate computing

students through a card-sorting exercise into none distinct categories. A

focus group of five HCI experts reviewed the categories to derive the final

set of 38 guidelines in 11 categories. The guidelines were validated through

a process of heuristic reviews of two Web sites targeting older people by six

participants with HCI experience. A final verification used a panel of

sixteen older web users (average age 59.2 years) to look at the same two

sites and rank he useful of each guideline from ‘one’ (useless) to

‘five’ (very useful) – all the guidelines were ranked ‘three’ of

above. The elderly users were also asked for any suggestions for missing

guidelines – eight additions were suggested that will be considered in

future developments (Zaphiris, Kurniawan and Ghiawdwala, 2006). Kurniawan,

Zaphiris and colleagues derived eleven categories of guidelines, termed

“SilverWeb Guidelines” by Zaphiris, Kurniawan and Ghiawdwala (2006), from

their review of previous HCI research:

- Target design – provide larger targets; confirmation of capture; no

double-clicking (?)

- Graphics – ensure their relevance; provide alt attributes; icons

clear and meaningful

- Navigation – provide bolder cues; clarity; avoid pull-down menus; use

shallow hierarchy with meaningful groupings

- Browser window features – avoid scroll bars; only one window and no

pop-ups

- Content layout design – use clear language; avoid irrelevant

information; highlight important information; concentrate information

mainly in the centre; provide clear and simple screen layout and

navigation

- Links – differentiate between visited and unvisited; clearly named

with similar links going to the same destination; provided in a bulleted

list and not tightly clustered

- User cognitive design – provide time for users to read the

information; reduce the demand on working memory by supporting

recognition rather than recall

- Use of colour and background – use colour conservatively; avoid blue

and green tones; background should be off-white with high contrast

foreground; content should not be in colour alone

- Text design – avoid moving text; use left justification; provide

increased leading ; avoid all capitals for main text; provide clear large

headings; use sans-serif font of 12-14 points

- Search engine – cater for spelling errors

- User feedback and support – provide a site map; provide an online

help tutorial; support user control and freedom; provide simple and easy

to follow error messages

Many of these guidelines are similar to the WCAG 1.0 Checklist, while

others mirror the recommendations of the usability-based guidelines and

checklists produced by others. Clark (2005) criticised many of the

recommendations as being irrelevant or too general, including:

- Double clicking – not required anyway on web pages

- Graphics should not be used for decoration – does away with graphic

design

- Avoid scroll bars – vertical scrolling is part of the web, if they

meant avoid horizontal scrolling they should say so

3.2.7 Webcredible’s guidelines (2006)

Fidgeon (2006) at Webcredible analysed eight usability sessions they had

undertaken with older users (over 65 years) and compared them with eight

similar session they had conducted with younger Web users (under 40 years).

Some of their comparisons were that older users used more emotive terms when

describing Web sites and were more likely to assign blame, to themselves,

when encountering difficulties. They also found that the elderly users often

failed to scroll down, thus missing key information, were less likely to

understand technical language, but had a higher propensity to use the search

facility than their younger counterparts. The older users also required over

twice the time to complete tasks than the younger users, maybe because they

read all the text on a page before selecting a link and/or because they were

more likely to click on text areas that were not links. Fidgeon and

Webcredible made nine suggestions for improving the usability of Web pages

for elderly users:

- Investigate ways to indicate that a page is not finished and requires

scrolling

- Avoid technical term is possible

- Identify links in a consistent and obvious way (blue, bold, and

underlined)

- The attention grabbing features on a page should be links

- Visited links should change colour

- Provide all content as HTML were possible (do not require users to

install software, not even Adobe Reader)

- Make the content as clear and concise as possible (consider providing

‘simple’ and ‘detailed’ versions)

- Provide a “make the writing bigger” link and always use high

contrast (e.g. black on an off-white background)

- Provide explicit instruction by using the imperative forms of verbs

(e.g. ‘Go to more details about XXX’)

Some of these recommendations reflect the WCAG 1.0 checkpoints; other are

designed to accommodate users without a technical Web background and

experience. Webcredible recommend these design features for all sites and

acknowledge a need for further investigation.

3.2.8 Common themes from existing Guidelines

Several other authors (e.g. SPRY,1999; Zhao, 2001; de Sales and Cybis,

2003; Moreno, 2007) have prepared guidelines and recommendations for

senior-friendly Web sites with most of the same recommendations as others.

With so many guidelines in existence, it is interesting to ask who knows

of them or uses them. Sloan (2006), acknowledging that WCAG 1.0 was the de

facto standard for Web site accessibility, undertook a survey of web

designers to see which ‘senior-friendly’ and other usability guidelines

Web designers and developers were aware of and used. In addition to Coyne and

Nielsen (2002), NIA/NLM (2002) and Kurniawan and Zaphiris (2005), Sloan

included:

- “Beyond ALT Text: Usability for disabled users” (Coyne and Nielsen,

2001)

- “Research-based Web design and usability guidelines” from the

National Cancer Council (NCC, 2004 [updated in 2006])

- “Guidelines for accessible and usable Web sites: Observing users who

work with screen readers” (Theofanis and Redish, 2005)

Sloan’s 57 respondents consistently responded “I’ve never heard of

them” to all but the Coyne and Nielsen publications with only a few

acknowledging that they had read or used them.

This lack of awareness, combined with the observed repetitiveness within

them, confirms the need for this project and publication.

Many common themes emerge from these … Questions to ask

include:

- What commonality is there across these guidelines?

- Which guidelines/recommendations address:

- Good usability

- Overcoming a lack of ICT/Web experience

- Aging specific functional limitations

- Within the cognition section – what is different between

cognitive impairments experienced by the elderly, and cognitive

impairments experienced by the general population?

- A similar question probably needs to be asked about vision

impairment and mobility impairment.

- What match is there to WCAG 2.0 SC?

3.3 WAI guidelines

The W3C Web Accessibility Initiative has released several sets of

guidelines to help make the Web more accessible to people with disabilities.

These include guidelines relating to the presentation of content (Web Content

Accessibility Guidelines), the accessibility of user agents, including

browsers (User Agent Accessibility Guidelines) and the requirements of

authoring tools, including blogs and online forums, for the creation of

accessible content and for use by people with disabilities (Authoring Tool

Accessibility Guidelines). As the Web has become an interactive medium, the

interrelationships between the guidelines and the users become increasingly

important to allow access to information and to allow the creation of

information.

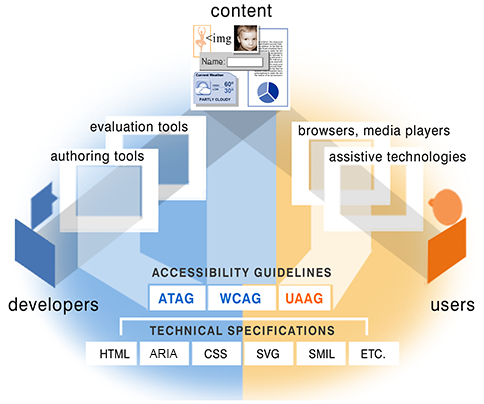

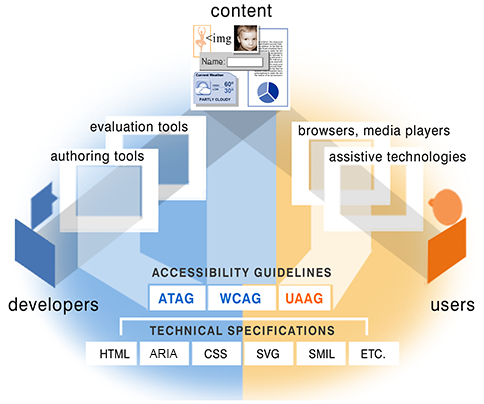

It is essential that several different components of Web development and

interaction work together in order for the Web to be accessible to people

with disabilities (Figure 7). These components include:

- content - the information in a Web page or Web application, including:

- natural information such as text, images, and sounds

- code or markup that defines structure, presentation, etc.

- Web browsers, media players, and other "user agents"

- assistive technology, in some cases - screen readers, alternative

keyboards, switches, scanning software, etc

- users' knowledge, experiences, and in some cases, adaptive strategies

using the Web

- developers - designers, coders, authors, etc., including developers

with disabilities and users who contribute content

- authoring tools - software that creates Web sites, including blogs,

content management systems, and learning management systems

- evaluation tools - Web accessibility evaluation tools, HTML validators,

CSS validators, etc.

Figure 7 - How the components of web accessibility relate to each

other (W3C, 200x)

The draft WCAG 2.0 has twelve guidelines for accessible content:

- 1.1 Text Alternatives: Provide text alternatives for any non-text

content so that it can be changed into other forms people need, such as

large print, braille, speech, symbols or simpler language

- 1.2 Synchronized Media: Provide synchronized alternatives for

synchronized media

- 1.3 Adaptable: Create content that can be presented in different ways

(for example simpler layout) without losing information or structure

- 1.4 Distinguishable: Make it easier for users to see and hear content

including separating foreground from background

- 2.1 Keyboard Accessible: Make all functionality available from a

keyboard

- 2.2 Enough Time: Provide users with disabilities enough time to read

and use content

- 2.3 Seizures: Do not design content in a way that is known to cause

seizures

- 2.4 Navigable: Provide ways to help users with disabilities navigate,

find content and determine where they are

- 3.1 Readable: Make text content readable and understandable

- 3.2 Predictable: Make Web pages appear and operate in predictable

ways

- 3.3 Input Assistance: Help users avoid and correct mistakes

- 4.1 Compatible: Maximize compatibility with current and future user

agents, including assistive technologies

The draft ATAG 2.0 has seven principles:

- PART A: Make the authoring tool user

interface accessible

- A.1: Authoring tool must facilitate access by assistive

technologies

- A.2: Authoring tool user interface must be perceivable

- A.3: Authoring tool user interface must be operable

- A.4: Authoring tool user interface must be understandable

- PART B: Support the production of accessible content

- B.1: Production of accessible content must be enabled

- B.2: Authors must be supported in the production of accessible

content

- B.3: Accessibility solutions must be promoted and integrated

The draft UAAG 2.0 has 5 principles:

- Follow applicable specifications and conventions

- Facilitate access by assistive technologies

- Ensure that the user interface is perceivable

- Ensure that the user interface is operable

- Ensure that the user interface is understandable

At the guidelines or principle level, it can be seen that most of these

will be required in order for an increasing number of elderly to be able to

access and interact with the Web in future. The detail within these

guidelines tells Web site developers, Web application developers, authoring

tool and blog developers, and browser and users agent developers, how to

achieve this.

3.4 Training the elderly to Use ICT and the Web

Dickinson et al. (2005) suggest that the provision of training courses to

overcome the lack of experience with computers and the Web of many elderly

people is a necessary short-term approach to encouraging participation in the

digital world. Computer and Web training can take the form of formal

class-based training, but also informal training by friends and family who

act as “coaches”. While many community groups and local libraries provide

computer and Web training for their elderly citizens , such as SeniorNett in

Norway (Bjørneby, 1999; Rogneflåten, 2004) there were few studies that

reported on this widespread activity. The studies identified around this

topic generally related to formal training situations established for

research purposes (e.g. UTOPIA ), and provide insights to the problems

experienced by the elderly online. Kantner and Rosenbaum (2003) undertook a

study with a small group of people who had undertaken the role of “coach”

to the elderly in Michigan in the USA to identify some of the problems

elderly computer user encounter, and some of the solutions. They interviewed

seven people who coached elderly people (65 years or older) to use computers

and the Web and asked them about the top two problems they had observed, and

about their training strategy. Ten common problems were observed by at least

4 of the coaches (Table 7) and a variety of solutions identified. Some of

these problems can be attributed to functional limitations associated with

ageing while others (e.g. files/folders, operating systems, and typing) are

more a result of lack of familiarity with ICT.

Table 7 - Problems identified by people coaching

seniors

Problem

|

Solutions

|

Dexterity, including:

Not anchoring the mouse or holding in straight; Moving the mouse

during clicking; Tremor or fine motor control during

fly-out/drop-down menu use

|

Demonstrate required action; send to special

“mousing class”; suggest trying various mice; checking desk

height; Teach alternative keystroke options (Alt keys, Enter,

arrows); using two hands for the mouse

|

Fear of making a mistake - Losing data or

‘breaking something’

|

Reassurance

|

Working with files/folders

|

Using the analogy of a filing cabinet; saving to

the desktop

|

Specifying searches (though understanding the

results was only identified as a problem by one participant)

|

‘work-in-pair’ activities

|

Too much information, including:

What is/isn’t an advertisement; Prevalence of ‘pop-up’ ads;

Clutter of portal pages

|

Switching the start page to Google; training in

advertisement recognition; training in clicking the “X” to close

pop-up windows

|

Using different computers and operating systems -

this became a problem with senior-centre classes when the attendees

returned home to practice, and sometimes when telephone coaching as

provided to family and friends.

|

No solution was evident for this problem, however

it was observed that it became an impediment to system upgrades, and

also posed a problem when Web sites were upgraded

|

Vision

|

Coaches were able to change the default font size

in Word, but didn’t know what to do for browsers or at the

operating system level.

One coach changed the resolution to 800x600 as a solution and

installed glare filters.

|

Working with attachments and downloading ( Email

attachments may be important documents)

|

Generally the users did not download programs or

files from the Web.

|

Typing

|

Practice was the only solution, and preparing ahead

of going to the computer for some activities.

|

When asked about suggestions for making the Internet easier for seniors to

use, the suggestions included:

- Simpler pages; fewer [browser?] buttons

- Clearer Back/Forward option, including having the Back button in a new

window closing it and returning the user to the window and page where it

was linked from

- Search to display result in associated grouping (like ecommerce

sites)

- Fewer pop-ups

With respect to the accessibility settings available, three coaches had

not thought of it, one did not have the authority, and three had adjusted the

mouse settings.

Kantner and Rosenbaum recommended that success stories from caches need to

be collected and published so that other can learn from their experiences.

The experience of the University of Dundee (Dickinson et al. 2005)

reflected many of the experiences of the Michigan coaches reported earlier by

Kantner and Rosenbaum, including a lack of knowledge and confidence, and

confusion about searching. The UTOPIA team at the University of Dundee in

Scotland was approached to teach a class of older adults to use computers and

the Web. Of the twelve initial participants (five were 55-65 years; fiver

were 65-74 years; two were over 75 years), one had hearing loss, one had

impaired fine motor control as a result of stroke, one was dyslexic and ten

of them required reading glasses. As experienced computer users themselves,

the researchers conducting the classes had to recognise that their own

knowledge was a potential problem.

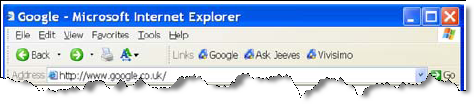

To reduce the software complexity, the interfaces to Word, Outlook Express

and Internet Explorer (IE) were simplified (e.g. Figure 8). Even with the

reduced IE interface, users became confused when trying to search and often

used the address bar instead of the search engine input box. The learners

were also surprised when search results loaded a PDF document, and often

missed the PDF icon often associated with these files. Drop-down lists

allowing for search refinement often confused the participant too.

Figure 8 - The simplified IE interface used at the University of

Dundee

Dickinson et al. endorsed WAI’s guidelines in contributing to the

accessibility of Web sites to elderly users, but suggested that that browser

changes could also make significant differences to older learner’s

experience. Compared with the simplified IE interface they worked with,

(Figure 8) they emphasised the value of the Home button, and questioned the

value of the ‘forward arrow’ and the address bar. The experience at the

University of Dundee also emphasised the importance of written combined with

hand-on support for older learners.

Hawthorn (2005) also stresses the importance of simplifying the interface

for older users new to computers and the Web. Hawthorn worked with a group of

25 older users (average age 70 years) to teach them file management skills

using a modification of the UTOPIA methodology (Eisma et al. 2004). Part of

simplifying the interface to the learning environment included large fonts,

high contrast, and simple sentence structure. Hawthorn found that building a

conceptual framework was possible, but that many of the participants required

time and active hands-on exercises.

In another UK study of an Internet training project called Care Online,

Osman et al (2005) report that, while most of the volunteers had no intention

of connecting to the internet before he project, the majority intended to

stay connected afterwards. The project included a portal with large button,

associated graphics and exceeding the accessibility requirements of WCAG 1.0

“single-a” accessibility. Like Hawthorn, Osman et al. found that

appropriate training and support was a key to elderly adults Web usage.

Papers still to discuss:

- Campbell and Wabby (2003) – the Elderly and the internet: a case

study (in training to access health information)

- Elliot, P. (1992). Assistive Technology for the Frail Elderly: An

Introduction and Overview, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/asttech.pdf

“…assistive technology has not been fully successful in the geriatric

marketplace… Experts attribute this to four factors: (a) inadequate

training and orientation for the elderly consumer; (b) inappropriate

match of assistive device to the person's need; (c) unwieldy designs; and

(d) failure to realize that assistive technology involves more than just

giving a person a device.”

3.5 Studies of elderly Web users’ specific

disabilities

General ageing studies … to be discussed here.

3.5.1 Mobility

In addition to the studies on the general issues of ageing, some studies

focused on the particular issues of mobility and dexterity with input

devices, specifically mouse use. No studies were identified which

investigated issues of keyboard use, although casual observation of the

authors own elderly family members indicates that this can be an impediment

to ICT usage.

Three studies have been considered here dealing with Parkinson’s

Disease, general ageing and pointing, and a possible solution via expanding

targets.

Keates and Trewin (2005) investigated the one of the common motor skill

diminishments associated with ageing – Parkinson’s Disease. In a previous

study Trewin and Pain (1999) found that people with motor disabilities had

error rates of greater than 10% when trying to point and click with a mouse

on small targets. The 2005 investigation included young adults, adults, older

adults (average age 79 years) and adults with Parkinson’s Disease (average

age 57 years); most of the participants were experienced mouse users.

Keates and Trewin found that seniors take longer to complete tasks, and

pause frequently, while initiating movement can be difficult for people with

Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease users were also observed to make

slight mouse movements while trying to press the button. Both of these groups

behaved differently from the behaviours predicted by the theoretical models

developed for able-bodied users. Pointing issues reported from this study and

another study (Paradise, Trewin and Keates, 2005) included:

- Keeping the hand steady when navigating

- Slipping off [multi-level] menus

- Losing the cursor

- Moving in the desired direction

- Running out of room on the mouse mat

- The mouse ball getting stuck

Some of these issues are related specifically to using the Web (e.g. menu

use) while others are more broadly disability-related (e.g. hand steadiness

and losing the cursor) or very broad ICT usability issues.

Jastrzembski et al (2005) undertook a study on input devices & and

age/hand effects. Their participants were experienced mouse users and they

were investigating whether age had any impact on mouse use and whether a

light pen may be a better input device for older users. Of their 72

participants, they had 24 young adults (median age 21.7 years), 25 middle

aged adults (median age 49.9 years) and 24 older adults (median age 70.9

years). The study involved both clicking, and data entry, to simulate

practical Web use.

While previous studies apparently showed preferences for direct pointing

devices such as light pen, supporting the observation that older adults

experience declines in spatial abilities and in motor control and

coordination, Jastrzembski et al showed that tasks requiring a combination of

keyboard entry and pointer were best completed with a mouse unless the user

was required to change from their preferred hand. Jastrzembski et al did

suggest that adjusting the mouse acceleration could be a tactic for improving

‘target acquisition’ among older novice users. Jastrzembski et al did not

comment on target size.

The third study by Bohan and Scarlett (2003) reviewed considered the

accommodation of older adults difficulties with mouse use via expanding

targets as the cursor approaches. Participants in this study were young

adults (median age 20 years) or elderly (median age 81 years), and all

reported to be daily computer users. Bohan and Young’s older adults took

significantly longer to acquire the ‘target’ than the younger adults,

regardless of target expansion, although early target expansion was found to

significantly help the older users almost as much as a stationary larger

target.

The first two studies highlighted mouse use issues faced by older ICT

users, while the final study suggested a possible Web site technique for

overcoming some of these.

3.5.2 Vision

Parker and Scharff (1998) in a study of contrast sensitivity and age on

readability, found that older adults (over 45 years) performed better with

high contrast and positive polarity. In particular, they found that “white

text presented on a black background (high-contrast, positive polarity) slows

reaction times compared with black text on a white background (high-contrast,

negative polarity). At the other [lower] contrast levels, polarity makes no

significant difference.” They also reported that the effect of polarity was

significant for the older age group but not for the younger (18 – 25 years)

group.

Some other studies to precede this one?

Bernard, Liao and Mills (2001) looked at what might be the best font for

older adults online bearing in mind the many age-related factors affecting

reading. They looked at legibility, reading time and general preference of

two types of serif and sans serif fonts at 12 and 14 point sizes. Two-thirds

of the 27 participants (mean age 70 years) regularly read material on