An Introduction to XHTML2

Steven Pemberton, W3C/CWI, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Status

This is an early draft, containing material from different sources. It is at the moment in a rough outline form, and may also contain some factual errors.

Introduction

XHTML2: all about extensibility.

HTML - a great success

But has become a sort of Garden of Eden, with lots of Thou Shalt Nots in the form of guidelines

- Accessibility guidelines

- Usability guidelines

- Internationalisation guidelines

- Metadata guidelines

- Device independence guidelines

etc, etc, etc

And these communities have all come to the XHTML2 working group to ask for new facilities.

XHTML2: The next generation in the XHTML family

In designing XHTML2, a number of design aims were kept in mind to help direct the design. These included:

- As generic XML as possible: if a facility exists in XML, try to use that rather than duplicating it. This means that it largely already works in existing browsers (main missing functionality XForms and XML Events).

- Less presentation, more structure: use stylesheets for defining presentation.

- More usability: within the constraints of XML, try to make the language easy to write, and make the resulting documents easy to use.

- More accessibility: 'designing for our future selves' – the design should be as inclusive as possible.

- Better internationalization .

- More device independence: new devices coming online, such as telephones, PDAs, tablets, televisions and so on mean that it is imperative to have a design that allows you to author once and render in different ways on different devices, rather than authoring new versions of the document for each type of device.

- Better forms: after a decade of experience, we now know how to make forms a better experience.

- Less scripting: achieving functionality through scripting is difficult for the author and restricts the type of user agent you can use to view the document. We have tried to identify current typical usage, and include those usages in markup.

- Better semantics: integrate XHTML into the Semantic Web.

Try to please as many people at once

Keep old communities happy

Keep new communities happy

Backwards compatibility

Earlier versions of HTML claimed to be backwards compatible with previous versions. For instance, HTML4

<meta name="author" content="Steven Pemberton"> puts the content in an attribute and not in the content of the element for this reason.

In fact, the only version of HTML that is in any sense backwards compatible is XHTML1 (others all added new functionality like forms and tables that would not work on older browsers).

XHTML2 takes advantage of CSS not to be element-wise backwards compatible, but architecturally backwards compatible.

For instance, much of XHTML2 works already in existing browsers.

A Simple Example

XHTML2 is recognisably a family member. In fact in the following simple example, there is no difference.

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en">

<head>

<title>Virtual Library</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Moved to <a href="http://example.org/">example.org</a>.</p>

</body>

</html>

XHTML2: "the one bright light"

"Is this a bright and shining star? I think so."

Structure and Presentation

Remove all presentation-oriented elements

Add more structuring elements

Use CSS for all presentation

The use of stylesheets

One single HTML file, with hundreds of beautiful, breathtaking stylesheets

Structure

One of the biggest problems for non-sighted people with many HTML pages is working out what the structure is. Often the only clue is the level of header used (h1, h2 etc), and often they are not used correctly.

To address this, in XHTML2 you can now make the structure of your documents more explicit, with the <section> and <h> elements.

<section>

<h>A heading</h>

...

<section>

<h>A lower-level heading</h>

...

</section>

</section>

Structuring advantages

Advantages include:

- easier to cut and paste and keep your heading levels consistent

- importing sections in PHP-like situations

- you are no longer restricted to 6 levels of header.

h1-h6 are currently still available.

<hr>

It is amazing how little issues can take so much effort.

A question that we often had to address was "is <hr> presentational?"

The Japanese community were also asking for a <vr>.

And then we had an aha moment...

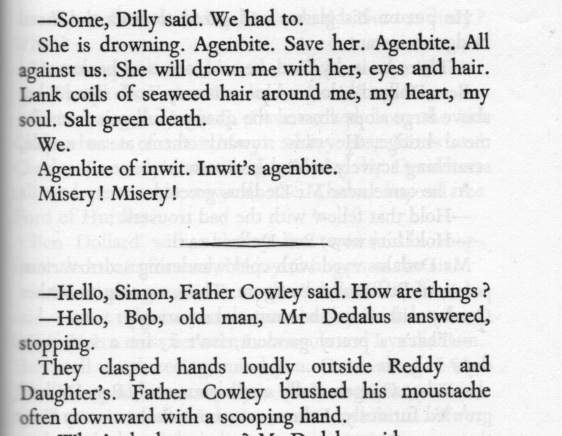

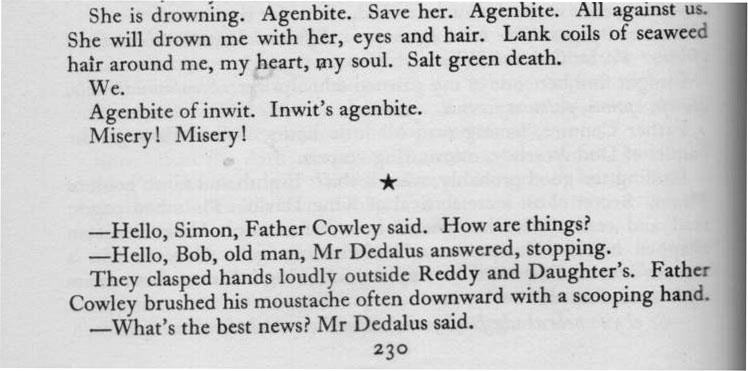

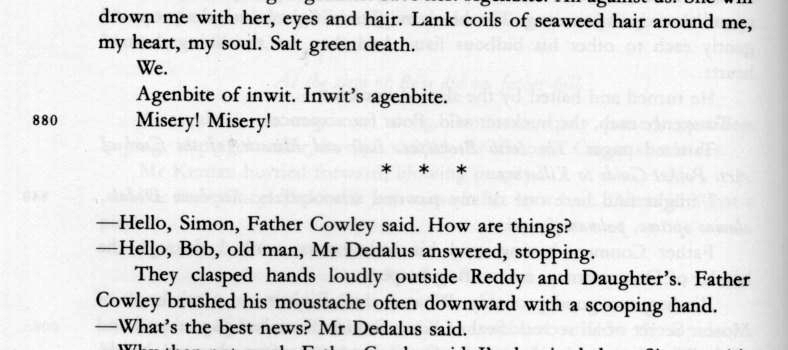

James Joyce Ulysses

Here are three examples of the same section from Ulysses in 3 different editions:

These are all <hr>s! <hr> is not presentational, but structural: a lightweight section separator.

The only thing wrong with <hr> is that it is not (necessarily) horizontal, and not (necessarily) a rule!

We already needed a separator element for navigation lists, so we just decided to do away with all the confusion and rename <hr> to <separator>.

Better paragraphs

A paragraph is now much closer to what people perceive as a paragraph. For instance, this is now allowed:

<p>Advantages include: <ul> <li>easier to cut and paste and keep your heading levels consistent.</li> <li>importing sections in PHP-like situations</li> <li>you are no longer restricted to 6 levels of header.</li> </ul> </p>

Images

You might be surprised to know that <img> was not in the original HTML.

<img> is actually badly designed:

- Not backwards compatible :-)

- No fallback except the alt text (this seriously impeded the acceptance of PNG images)

- The alt text can't be marked up

- Longdesc is hard to use, seldom implemented, and seldom used.

So what has been done is allow the src attribute on any element. The image replaces the element content, and the element content is fallback. Essentially we have added fallback, moved the longdesc into the document, merged it with alt, and allowed it to be marked up all in one go.

<p src="map.gif">Walk down the steps from the platform turn left, and walk on to the end of the street</p>

The <img> element is still available, but the alt text goes in the content:

<img src="w3c.png">W3C</img>

Image types

HTML4 has the 'type' attribute in a number of places as a hint to the browser as to what it could expect if it went and got a resource.

But it is pretty useless. Some browsers ignore it, some don't.

Now it is a specification of the type, and meshes with the HTTP accept: field. This means that

<p src="map" type="image/gif">...

will give you a GIF, or otherwise give you the fallback.

Similarly, you can write:

<p src="map" type="image/png, image/gif">... <p src="map" type="image/*">...

Leaving the type attribute off is equivalent to saying

type="*/*"

Whitespace and pre

In HTML the only method to retain whitespace in content is with

<pre>.

IN XHTML2, all elements can use the attribute

layout="relevant".

<p class="poem" layout="relevant"> ... </p>

This doesn't impose a fixed-width font on the output, just that spaces and newlines are preserved.

Lines

<br/> splits a paragraph into different parts, but they are unaddressable with CSS. So alongside a breaking element, XHTML2 also has a structuring element:

<p>Steven Pemberton<br/> CWI/W3C<br/> Amsterdam</p>

can now be expressed:

<p> <l>Steven Pemberton</l> <l>CWI/W3C</l> <l>Amsterdam</l> </p>

This gives you many more presentational possibilities, such as automatic

numbering of lines, or colouring of alternate lines, etc.

Hypertext

In a non-backwards compatible step, HTML4 allowed any element to become the

target of a link (with id on any element).

XHTML2 extends this by now allowing any element to become the source of a

link as well, by allowing href anywhere.

So, instead of

<li><a href="http://www.w3.org/">W3C</a></li>

you may now write

<li href="http://www.w3.org/">W3C</li>

though <a> is still available.

Navigation lists

One thing you see everywhere on the web are menus for navigation, implemented with script.

XHTML2 now supports these natively:

<nl> <label>Go</label> <li href="/">Home</li> <li href="/TR/">Technical reports</li> ... </nl>

Whether they are presented as menus, or in some other way, depends on the platform, the stylesheet, etc.

dir, edit

Certain things that used to be done with elements are now done with attributes: <ins> <del> <bdo>

<p edit="inserted">

and

<span dir="rlo">...

media

In certain places in HTML4/XHTML1 you can say that an element applies only to a specific media, like:

<style media="print" ...>...

This now applies across XHTML2, to any element.

<p media="screen">This text is only visible on a screen, not on the printed or projected version</p>

Metadata

Metadata is becoming one of the most important new features of the web. The Semantic Web community has been working for years to integrate metadata properly with XHTML.

Metadata is sprinkled across HTML in lots of places:

- The <title> element

- The <meta> element

- The <link> element

- The cite attribute

- The title attribute

etc etc.

XHTML2 creates a unified story about metadata, by relating it to RDF, however without confronting the HTML author with RDF.

RDF

RDF is a concept, with several possible external representations (or serialisations, as they are referred to).

Essentially, RDF consists of a collection of facts, or more properly assertions.

Each assertion is about some resource (identified by a URL), and gives a property that that resource has, and a value for that property.

The property is always identified by a URL.

The value of the property may be a URL, a string, or a piece of XML.

(By the way, you can also make assertions about things that haven't got

URLs, in which case they are referred to as blank nodes. For instance,

"There is a person that has an email address of steven@w3.org",

and he is called "Steven Pemberton".)

RDF Terminology

Unfortunately, the RDF community tends to use terminology that refers to the mechanics of RDF, rather than its purpose.

So they tend to call an assertion a triple, call the thing it is about the subject, the property a predicate, and the value of the property the object.

So be it.

Example

So when we say that the title of this document is "XHTML2 and XForms", and its author is called Steven Pemberton, we say

<http://www.w3.org/2006/...this document...> <http://.../title> "XHTML2 and XForms"

<http://www.w3.org/2006/...this document...> <http://.../creator> "Steven Pemberton"

So what?

RDF is the basis for the Semantic Web

It is a very simple, flexible mechanism for representing knowledge.

There are RDF databases and inference engines emerging that can represent the knowledge, and work out conclusions from it.

Improved searches

If a search engine or a browser can work out more about your document than just the text that is in it, searches and other interactions can become better.

For instance, if it can work out that in a page the text "the prime minister" refers to Tony Blair, then a search for Tony Blair could take you to that page, even if it doesn't mention him by name.

If the browser can work out that some text is an address, it can offer to add it to your address book, or find it on a map.

If a browser can work out that some text is for a conference, it could offer to add it to your calendar, or find flights and hotels.

RDF Serialisations

As mentioned, there are several RDF serialisations, such as 'triples' (above), and RDF/XML.

XHTML2 introduces a new representation for RDF assertions by leveraging the existing <meta> and <link> elements of HTML.

RDF/XML Example

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar">

<ex:editor>

<rdf:Description>

<ex:homePage rdf:resource="http://purl.org/net/dajobe/"/>

<ex:fullName>Dave Beckett</ex:fullName>

</rdf:Description>

</ex:editor>

<dc:title>RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised)</dc:title>

</rdf:Description>

This says that the document "http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar":

- has the title "RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised)"

- was edited by someone with the name "Dave Beckett"

- who has a homepage at "http://purl.org/net/dajobe/"

In XHTML2

@@

<p about="http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar">

<span property="ex:editor">

<a rel="ex:homePage" href="http://purl.org/net/dajobe/" property="ex:fullName">Dave Beckett</a>

</span>

<span property="dc:title">RDF/XML Syntax Specification (Revised)</span>

</p>

'about' gives the subject (defaults to the current document)

'property' gives the predicate for a string or XML fragment; the object is in the element content (or the 'content' attribute).

'rel' gives the predicate for a URL: the object is in the href.

Generalising meta

The attributes on <meta> and <link> can be used on any element. For instance:

<body>

<h property="title">My Life and Times</h>

...

is a way of saying that "My Life and Times" is both the <title> of this document, as the top-level heading.

You could do the following in HTML already, but now we can extract it as RDF as well:

This work is licensed under the <a rel="dc:rights"

href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/">

Creative Commons Attribution License</a>.

There areş standard filters for extracting the RDF.

Why this solution is nice

You can explain it using HTML concepts.

If you don't care, you can just ignore it.

It doesn't require you to learn how to use RDF to be able to benefit from it.

The RDF community get their triples without RDF being imposed on the HTML community.

Problems solved

This approach solves a lot of outstanding problems.

For instance, the Internationalisation community needed a way of adding

markup to a title attribute. Now we can just say that

<p title="whatever">

is equivalent to:

<p> <meta property="title">whatever</meta>

And it solves the problem of everyone asking for new elements in XHTML: an element for <navigation>, an element for <note>s (in inline and block versions), an element for lengths, and numbers, and ...

But first a diversion...

role

The accessibility community needed a way to specify what a particular element was for.

Some examples: that a certain <div> was just a navbar, that another <div> was the main content, etc. So we introduced the 'role' attribute for this. You can now say:

<div role="navigation">...</div> ... <div role="main">...</div>

but once we had that mechanism, it allowed us to add any semantics we wanted, layering it on top of the structure. For example:

<p role="note">...

but also

<span role="note">...

<table role="note">...

role values

role is in a way like class but with meaningful

(semantic) values.

In fact, anyone can add their own role values, so that whole communities can agree on new semantics to overlay on to the content.

Apparently the mobile and device-independent communities (as well as accessibility) are very excited about the possibilities of using role.

In fact, you don't really need RSS anymore:

<h role="rss:title">... <p role="rss:description">...

Access key

To go with the role attribute, there is a new way of doing accesskey (which used to be spread through the document). Now in the head you can say things like:

<access targetrole="main" key="M"/>

An advantage of this is that you can have different access keys for different media.

(There is also a targetid for individual elements.)

Events

Events in HTML are very restrictive:

- the event name is hard-wired into the language, rather than being a

parameter, so that to be able to deal with a new sort of event you have to

add a new attribute, like

onflashif an event called flash were introduced. - the event name is usually very hardware specific, such as click, when in fact you don't care how the button is activated, only that is has been activated

- you can only use one scripting language (since you can't have two attributes called onclick, one for JavaScript and one for VB)

- event handling and markup are intertwined — there are no ways to separate the two.

So we invented a new markup for events.

XML Events

<input type="submit" onclick="validate(); return true;">

is now

<input type="submit">

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/javascript">

validate();

</handler>

</input>

We renamed <script> to <handler> because it is sufficiently

different to the HTML <script> to be confusing. In particular

document.write no longer works in XML.

This approach now allows you to specify handlers for different scripting languages:

<input type="submit">

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/javascript">

...

</handler>

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/vbs">

...

</handler>

</input>

and/or different events:

<input type="submit">

<handler ev:event="DOMActivate" type="text/javascript">

...

</handler>

<handler ev:event="DOMFocusIn" type="text/javascript">

...

</handler>

</input>

@@XFrames

HTML Frames created several usability problem that caused several commentators to advise Web site builders to avoid them at all costs. Examples are:

- The [back] button works unintuitively in many cases.

- You cannot bookmark a collection of documents in a frameset.

- If you do a [reload], the result may be different to what you had (and you usually can't reload just one frame).

- [page up] and [page down] are often hard to do.

- You can get trapped in a frameset.

- Searching finds HTML pages, not Framed pages, so search results usually give you pages without the navigation context that they were intended to be in.

- Since you can't content negotiatiate,

noframesmarkup is necessary for user agents that don't support frames. However, almost no one produces noframes content, and so it ruins Web searches, since search engines are examples of user agents that do not support frames. - There are security problems caused by the fact that it is not visible to the user when different frames come from different sources.

XFrames defines a separate XML application, not a part of XHTML2 per se, that allows similar functionality to HTML Frames, with fewer usability problems, principally by making the content of the frameset visible in its URI.

There are already 2 implementations (XSmiles, DENG)

Example XFrames

<frames xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2002/06/xframes/">

<head>

<title>Home page</title>

<style type="text/css">

#banner {height: 10em }

#atoz, #nav {width: 20%}

#footer {height: 4em }

</style>

</head>

<group compose="vertical">

<frame id="banner" source="banner.xhtml"/>

<group compose="horizontal">

<frame id="atoz" source="atoz.xhtml"/>

<frame id="main" source="news.xhtml"/>

<frame id="nav" source="nav.xhtml"/>

</group>

<frame id="footer" source="copyright.xhtml"/>

</group>

</frames>

home.xframes#frames(main=a.xhtml,banner=b.xhtml)

XForms: the new Web Forms language

The major new functionality in XHTML2 is the forms language, XForms.

HTML Forms: a great success!

- Forms have been the basis of the e-commerce revolution

- You find them everywhere on the web

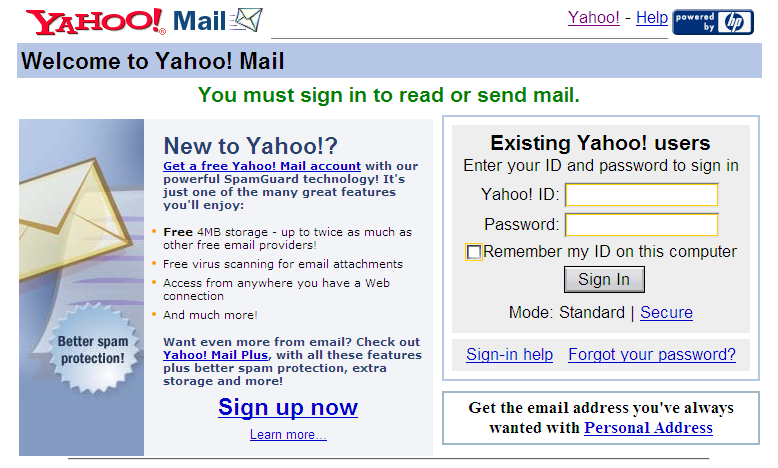

Searching

Buying

Logging in

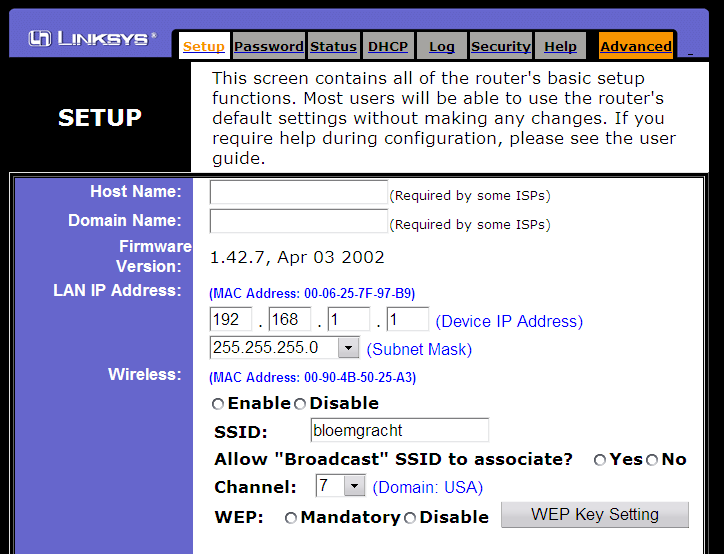

Configuring hardware

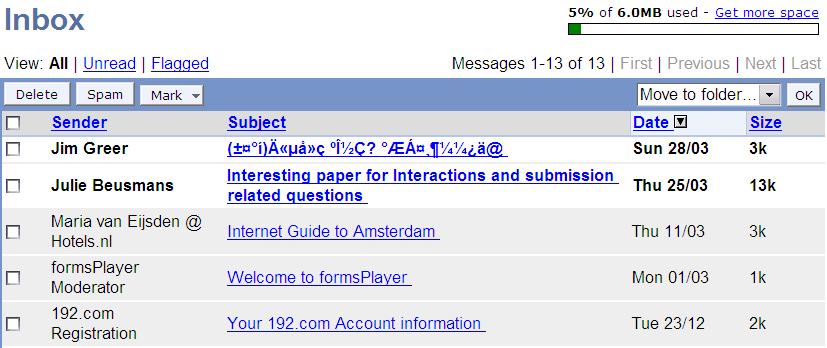

Reading mail

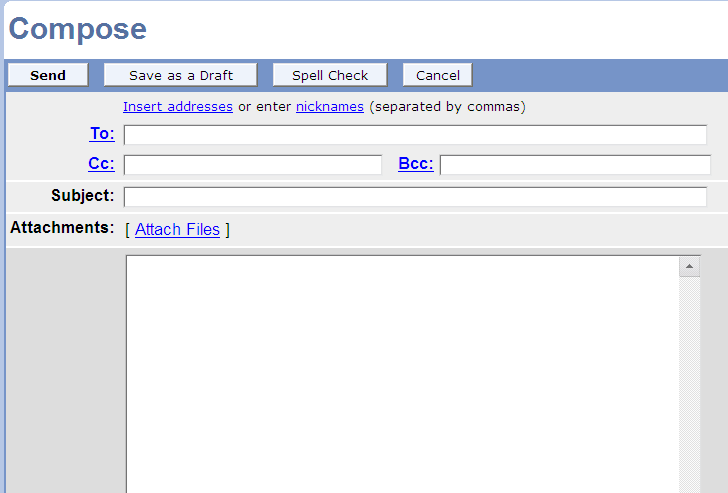

Composing email

Etc etc

- Tracking packages

- calculating currencies

- submitting taxes

- banking

- expenses

- calendars

- blogging

- wiki

- ...

So why XForms?

After a decade of experience with HTML Forms, we now know more about what we need and how to achieve it.

Problems with HTML Forms

- Presentation oriented, mixing data and presentation

- No types, Ping-ponging to the server

- Reliance on scripting

- Problems with non-Western characters

- Accessibility problems

- Hard to make cross-device for single authoring

- Impoverished data-model, no integration with existing streams

- Hard to manage, hard to see what is returned

- No support for wizards and shopping carts etc.

Soundbite: "Javascript accounts for 90% of our headaches in complex forms, and is extremely brittle and unmaintainable."

XForms, the Approach and the Advantages

XForms has been designed based on an analysis of HTML Forms, what they can do, and what they can't.

The Essence: Separation of Values from Controls

There are two parts to the essence of XForms. The first is to separate what

is being returned from how the values are filled in.

- The model specifies the values being collected (the

instance), and their related logic:

- Types, restrictions

- Initial values, Relations between values

- The body of the document then binds forms controls to values in the instance

The Essence: Intent-based Controls

The second part is that the form controls, rather than expressing how they should look (radio buttons, menu, etc), express their intent (this control selects one value from a list).

You then use styling to say how they should be represented, possibly with different styling for different devices (as a menu on a small screen, as radio buttons on a large screen).

Colour: red green blue

Overview of Advantages

XForms gives many advantages over classic HTML Forms:

XForms improves the user experience

XForms has been designed to allow much to be checked by the browser, such as

- types of fields being filled in

- that a particular field is required

- or that one date is later than another.

This reduces the need for round trips to the server or for extensive script-based solutions, and improves the user experience by giving immediate feedback on what is being filled in.

It is easier to author and maintain complicated forms

Because XForms uses declarative markup to declare properties of values, and to build relationships between values, it is much easier for the author to create complicated, adaptive forms, and doesn't rely on scripting.

An HTML Form converted to XForms looks pretty much the same, but when you start to build forms that HTML wasn't designed for, XForms becomes much simpler.

It is XML, and it can submit XML

XForms is properly integrated into XML: it is in XML, the data it collects in the form is XML, it can load external XML documents as initial data, and can submit the results as XML.

By including the user in the XML pipeline, it at last means you can have end-to-end XML, right up to the user's desktop.

However, it still supports 'legacy' servers.

XForms is also a part of XHTML2.

It combines existing technologies

Rather than reinventing the wheel, XForms uses a number of existing XML technologies, such as

- XPath for addressing and calculating values

- XML Schema for defining data types.

This has a dual benefit:

- ease of learning for people who already know these technologies

- the ability for implementors to use off-the-shelf components to build their systems.

It integrates into existing data streams

Data can be pre-loaded into a form from external sources.

Existing Schemas can be used.

It integrates with SOAP and XML RPC.

Doesn't require new server infrastructure.

It is device independent

Thanks to the intent-based controls, the same form can be delivered without change to a traditional browser, a PDA, a mobile phone, a voice browser, and even some more exotic emerging clients such as an Instant Messenger.

This greatly eases providing forms to a wide audience, since forms only need to be authored once.

It is internationalized

Thanks to using XML, there are no problems with loading and submitting non-Western data.

It is accessible

XForms has been designed so that it will work equally well with accessible technologies (for instance for blind users) and with traditional visual browsers.

It is rather easy to implement

XMLDOMCSSJavascriptXHTMLXPathXForms