Transcript

My name's Alice Boxhall.

I work at Google on accessibility in Chrome and, as Dominique said, I am also on the Technical Architecture Group of W3C.

And I want to talk a bit about the relationship between accessibility and innovation.

So...

Okay.

How often have you heard we don't have time or we don't have the resources to implement accessibility.

Particularly when you're trying to push boundaries and innovate, accessibility is often portrayed as this kind of annoying set of check boxes that just gets in the way. Even when you're not really trying to do something, you not trying to innovate but you just trying to do something quickly.

Accessibility is often seen as this kind of a drag, this optional thing that you can cut for time.

So I'd like to read through the case for all of you that accessibility and innovation actually go hand in hand.

And that as an industry we are missing all kinds of opportunities when we don't consider accessibility to be a fundamental core part of building any user interface.

I also have kind of a hobby. I'm really fascinated by the way that solving problems experienced by people with disabilities has always created innovation through the history of technology.

These are real acute problems and as we all know necessity and invention go together.

So I'd like to go through a few examples from recent technology, recent history of technology of how accessibility has driven innovations that you're probably familiar with. And then talk a little about how we can innovate better on the web.

So the first example I'd like to talk about is the typewriter. And I apologize in advance to any Italians or Italian speakers for my attempts to pronounce Italian names.

So the Contessa Carolina Fantoni de Fivizzano inspired the development of the earliest working mechanical typewriter in Italy in the early 1800s after she began to lose her sight.

So there's a couple of different versions of this story. Conflicting accounts give credit to her brother, Agostino Fantoni de Fivizzano and her dear friend, Pellegrino Turri. So I am inclined to give credit to all three of them because I know who gets written out of history.

The machine gave the Contessa the ability, the agency to correspond with her dear friend Turri in private without assistance.

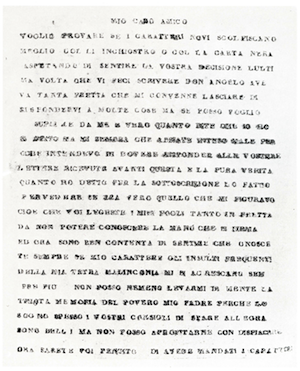

We don't really know what the machine looks like but there are some letters, some original letters from this device that survive like this one. And then you can see at the top it is addressed "Mio caro amico", "my dear friend".

So unfortunately for her they're not so private anymore but they are luckily for us a part of technological history.

This development also included the development of carbon paper which will be familiar if you've ever had a a handwritten receipt of CC'd someone on email.

The second example I'd like to talk about is Braille.

So interestingly enough the history of Braille actually began in the Napoleonic wars with the invention of night writing which was intended to be, to allow soldiers to be able to communicate silently and without any light so that they would not give away their position to the enemy.

It was this quite complex, unwieldy system with a matrix, a five by five matrix of sounds and then there was a two five dot columns and you were supposed to mark the column one on each column for the x and y position of the matrix and it was quite difficult to use. It didn't really catch on.

But it found sort of a new home in schools and institutes for the blind. It still wasn't really usable and the innovator who took this cumbersome system and turned it into the elegant simplified Braille scheme that we are familiar with today was a teenage kid who lost his sight as a young child.

So it was obviously Louis Braille and Louis had largely finished developing this six dot system by 1824 when he was only 15 years old. The critical insight that he had was that each glyph should be able to be read instantly via fingertip.

So this is were the night writing system fell down: it was quite slow to read. Louis's system was a lot more rapid.

It took a little while to catch on in part because there was a competing system based on written letter forms which was slower to read but was trying to be encouraged so that sighted people could read the same system.

Anyway by the time, I think, three years after Louis Braille passed away, the braille system became the absolute standard in schools for the blind.

And one sort of interesting tidbit is that one factor in the eventual widespread adoption of braille was this whole braille writer which was invented by Frank Haven Hall who worked at an institute for the blind in America.

He brought his experience working on this device particularly the lever action of the things that was punching out these braille cells to a collaboration with Christopher Latham Sholes and Samuel W. Soule to develop the first commercial typewriter which is the origin of the familiar QWERTY keyboard.

So I would like to briefly touch on teletype, SMS, and the deaf community.

Before the advent of electronic text messages deaf people were reliant on large teletype devices like this one.

So as well as being cumbersome these devices had another serious drawback which is the protocol they used to send and receive characters was a half duplex protocol meaning that if both ends tried to type at the same time the message would be garbled.

It also means that it was quite slow and it could only send 10 characters per second. When you type quickly it's not very many.

So deaf users developed a lexicon of abbreviations to reduce the character count. Some of these might look familiar such as msg for message, letter u for you, letter r for are, cuz for because and so on.

So with the advent of SMS message servicing and particularly flip phones deaf people were some of the earliest adopters of text messaging and they brought these abbreviations over to and habits over with them to the new technology.

And since it was available in virtually every mobile device it opened up communication opportunities for a lot of people in the deaf community who didn't necessarily have access to these teletype devices.

Another tangent, speaking of hearing impairment, one very prominent figure in the early development of the internet was Vint Cerf who is hard of hearing, incidentally like I am, and he said that he found email, which predated the internet, very attractive because it replaced voice calls where he couldn't necessarily catch everything that was going on or he'd have to ask people to repeat themselves, with the clarity of text where he could just read it in his own time. And the development of the internet was undertaken in the context of the very heavy use of email.

Next I would like to talk a little bit about the link between Cerebral Palsy, Switch Devices and NASA.

This is Christopher Hills who is a young Australian man with severe cerebral Palsy.

Since he has extremely limited motor control he's highly proficient with these switch devices. You can see in the photo he is sitting in a chair. He has a headrest that I think he's covering a couple of switches but there is a green and a red one visible. So he can, he's very proficient at tapping those with his head. These allow compatible software interfaces to be driven by taps on a switch to bias like a sewing machine pedal.

He has consulted with a number of organizations but the one that makes me the most excited is that he, so he's not only a certified video producer he has his own YouTube channel.

He's actually being consulted by NASA. And this is a still from a video that Chris produced and is on his channel.

NASA consulted with him to advise on the design and use of interfaces that are going to be used by astronauts wearing bulky space suits to communicate and perform other tasks on a tablet while walking in space.

So I just though that was so awesome.

Lastly I would like to touch on video games accessibility.

So speaking of sort of innovation, video games is something that not only pushing the boundaries of user interfaces and sort of interactions, they are also, you might arguably, sort of designed to test, to test and rely on specific physical abilities.

So the field of video games is actually undergoing something of an accessibility innovation renaissance right now which is really exciting.

This is largely thanks to the highly effective advocacy of a group of disabled gamers called, the able gamers and investment from several game studios including Microsoft with their amazing assistive controller that they unveiled a while back.

So if you play video games and you've ever turned on subtitles you probably have this group to thank.

So one of my favorite examples of an accessible video game, which actually happened just sort of somewhat incidentally, but really, really cool, is the Street Fighter series.

So because the sound design of the game is so intricate and detailed, it provides almost as much information as the visual design, meaning that a blind gamer, Sven Van de Wege, is able to play professionally and compete in tournaments.

So to bring this back to the web I don't believe that innovation is ever the result of a lone individual but it tends to arise from the application of the right skills to the right problems.

I hope that the examples I've shown in this talk have shown that disability is a powerful driver for both of those factors.

I also believe that like any other form of diversity inclusion, making sure that we include people with disabilities and that development of web technology will inevitably lead to greater innovation.

However, as with many forms of diversity inclusion, we have a vicious cycle which perpetuates this exclusion.

Simply put, because our tools and frameworks aren't always accessible, we are implicitly excluding people with disabilities who would naturally be in the best position to improve the state of accessibility and drive innovation.

This systematic exclusion has also helped create the situation where it can be too much work.

It can be more than it really should be to make basic web applications accessible.

This is because the frameworks and user experience patterns that allow us to rapidly develop an application have not always been designed and built with accessibility in mind.

I think the way out of this vicious circle is for all of us to think of this as a kind of technical debt that we all need to work on together.

I would love to see a future where knowing the basics of accessibility is considered as core a part of front end work as something like progressive enhancement or responsive design.

I'm also really excited by the trend in web standards that seems to be bringing accessibility back into the core again.

And I'm excited to see Melanie's talk following mine talking about a new accessibility future for high contrast and CSS.

For the rest of you, for all the web developers in particular in the audience, I would love to encourage you all to make a little time to learn a bit more about accessibility on the web.

So this is where I promote my own work.

A few years back a colleague and I made a free accessibility course on Udacity which you can find bit.ly/web-a11y completely free, no ads. If you, via that link, if you end up on a page that tries to get you to pay that's something else. Go to that link bit.ly/web-a11y. It covers focus, semantics, ARIA, and styling for accessibility, as well as a look at how people with various disabilities interact with web content.

Thank you so much for listening and you can find me on Twitter as sundress.