1. Introduction

The web is a rich, distributed repository of interconnected

information. Until recently, it was organized primarily for

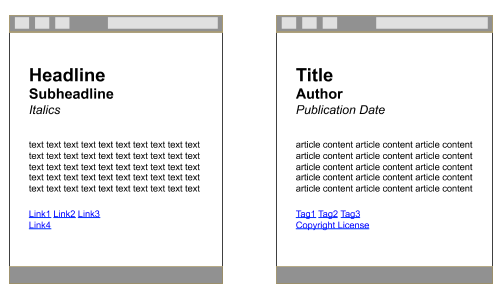

human consumption. On a typical web page, an HTML author might

specify a headline, then a smaller sub-headline, a block of

italicized text, a few paragraphs of average-size text, and,

finally, a few single-word links. Web browsers will follow these

presentation instructions faithfully. However, only the human

mind understands what the headline expresses—a blog post title.

The sub-headline indicates the author, the italicized text is

the article's publication date, and the single-word links are

subject categories. Computers do not understand the nuances

between the information; the gap between what programs and

humans understand is large.

What if the browser, or any machine consumer such as a Web

crawler, received information on the meaning of a web page’s

visual elements? A dinner party announced on a blog could be

easily copied to the user’s calendar, an author’s complete

contact information to the user’s address book. Users could

automatically recall previously browsed articles according to

categorization labels (i.e., tags). A photo copied and pasted

from a web site to a school report would carry with it a link

back to the photographer, giving him proper credit. A link

shared by a user to his social network contacts would

automatically carry additional data pulled from the original web

page: a thumbnail, an author, and a specific title. When web

data meant for humans is augmented with hints meant for computer

programs, these programs become significantly more helpful,

because they begin to understand the data’s structure.

RDFa allows HTML authors to do just that. Using a few simple

HTML attributes, authors can mark up human-readable data with

machine-readable indicators for browsers and other programs to

interpret. A web page can include markup for items as simple as

the title of an article, or as complex as a user's complete

social network.

RDFa benefits from the power of RDF [RDF-PRIMER], the W3C’s

standard for interoperable machine-readable data. However,

readers of this document are not expected to understand RDF,

only a basic level of HTML.

1.1 HTML vs. XHTML

Historically, RDFa 1.0 [RDFA-SYNTAX] was specified only

for XHTML. RDFa 1.1 [RDFA-CORE] is the newest version and

the one used in this document. RDFa 1.1 is specified for both

XHTML [XHTML-RDFA] and HTML5 [HTML-RDFA]. In fact, RDFa

1.1 also works for any XML-based languages like SVG [SVG12].

This document uses HTML in all of the examples; for

simplicity, we use the term “HTML” throughout this document to

refer to all of the HTML-family languages.

1.2 Validation

RDFa is based on attributes. While some of the HTML

attributes (e.g., href, rel) have

been re-used, other RDFa 1.1 attributes are new. This is

important because some of the (X)HTML validators may not

properly validate the HTML code until they are updated to

recognize the new RDFa 1.1 attributes. This is rarely a

problem in practice since browsers simply ignore attributes

that they do not recognize. None of the RDFa-specific

attributes have any effect on the visual display of the HTML

content. Authors do not have to worry about pages marked up

with RDFa looking any different to a human being from pages

not marked up with RDFa.

2. Adding Machine-Readable Hints to Web Pages

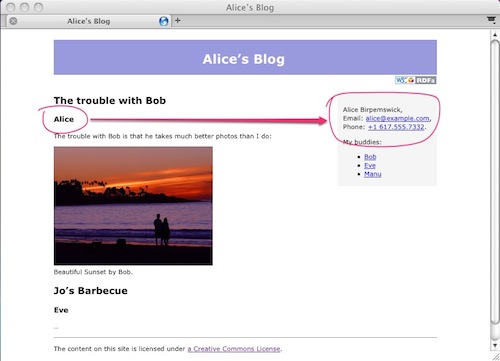

Consider Alice, a blogger who publishes a mix of professional

and personal articles at http://example.com/alice.

We will construct markup examples to illustrate how Alice can

use RDFa. The complete markup of these examples are available on a dedicated page.

2.1 Hints on Social Networking Sites

Alice publishes a blog and would like to provide extra

structural information on her pages like the publication date

or the subject. She would like to use the terms defined in the

Dublin Core vocabulary [DC11], a set of terms that are

widely used by, for example, the publishing industry or

libraries. She can do this easily by using RDFa:

<html>

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/created" content="2011-09-10" />

<meta property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject" content="photography" />

...

</head>

...

(Notice the markup colored in red: these are the RDFa

“hints”.)

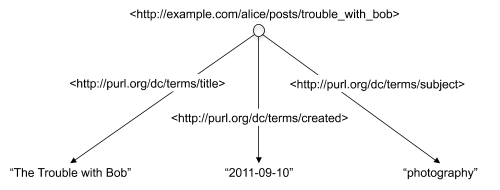

One useful way to visualize the structured data is:

It is worth emphasizing that RDFa uses URLs to identify just about everything.

This is why, instead of just using properties like title

and created, we use http://purl.org/dc/terms/title

and http://purl.org/dc/terms/created. The reason

behind this design decision is rooted in data portability,

consistency, and information sharing. Using URLs removes the

possibility for ambiguities in terminology. Without ensuring

that there is no ambiguity, the term “title” might mean “the

title of a work”, “a job title”, or “the deed for real-estate

property”. When each vocabulary term is a URL, a detailed

explanation for the vocabulary term is just one click away. It

allows anything, humans or machines, to follow the link to

find out what a particular vocabulary term means. By using a

URL to identify a particular type of title, for example http://purl.org/dc/terms/created,

both humans and machines can understand that the URL

unambiguously refers to the “Date of creation of the

resource”, such as a web page.

By using URLs as identifiers, RDFa provides a solid way of

disambiguating vocabulary terms. It becomes trivial to

determine whether or not vocabulary terms used in different

documents mean the same thing. If the URLs are the same, the

vocabulary terms mean the same thing. It also becomes very

easy to create new vocabulary terms and vocabulary documents.

If one can publish a document to the Web, one automatically

has the power to create a new vocabulary document containing

new vocabulary terms.

2.2 Indicating Title in the Text

As Alice adds her Dublin Core metadata, she notices that the

title of her page is already in the visible markup:

<div>

<h2>The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3>Alice</h3>

...

</div>

Alice can use the RDFa property attribute on

the h2 HTML element to indicate that this

existing rendered text should also be machine-readable text

indicating the page’s title:

<div>

<h2 property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3>Alice</h3>

...

</div>

Note that in the example above, Alice did not need to use

the content attribute, but could instead use the

text that already existed in the document. The property

attribute can be used on any element; by default, it

takes the text content of that element except if the content

attribute is present which then takes priority.

2.3 Links with Flavor

The previous example demonstrated how Alice can markup text

to make it machine readable. She would also like to mark up

the links in a machine-readable way, to express the type of

link being described. RDFa lets the publisher add a “flavor”

to an existing clickable link that machine processors can

understand. This makes the same markup help both humans and

machines.

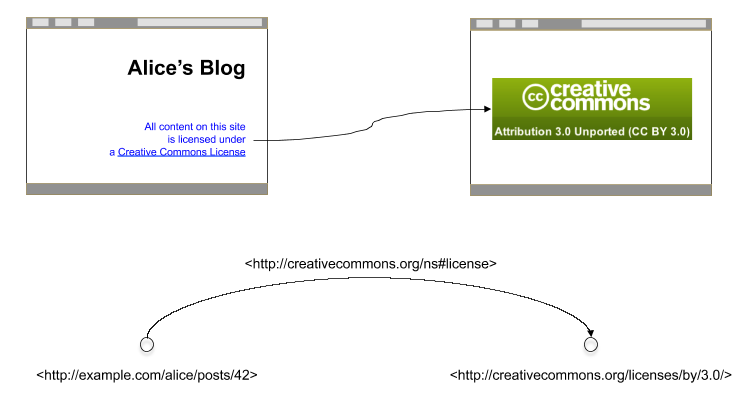

In her blog’s footer, Alice already declares her content to

be freely reusable, as long as she receives due credit when

her articles are cited. The HTML includes a link to a Creative

Commons [CC-ABOUT] license:

<p>All content on this site is licensed under

<a href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/">

a Creative Commons License</a>.</p>

A human clearly understands this sentence, in particular the

meaning of the link with respect to the current

document: it indicates the document’s license, the conditions

under which the page’s contents are distributed.

Unfortunately, when Bob visits Alice’s blog, his browser sees

only a plain link that could just as well point to one of

Alice’s friends or to her CV. For Bob’s browser to understand

that this link actually points to the document’s licensing

terms, Alice needs to add some flavor, some

indication of what kind of link this is.

She can add this flavor using again the property

attribute. Indeed, when the element contains the href attribute,

property is automatically associated with the value of this attribute

rather than the textual content of the a element. The value of the

attribute is the http://creativecommons.org/ns#license,

defined by the Creative Commons:

<p>All content on this site is licensed under

<a property="http://creativecommons.org/ns#license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/">

a Creative Commons License</a>.</p>

With this small update, Bob’s browser will now understand

that this link has a flavor: it indicates the blog’s license:

Alice is quite pleased that she was able to add only

structured-data hints via RDFa, never having to repeat the

content of her text or the URL of her clickable links.

2.4 Setting a Default Vocabulary

In a number of simple use cases, such as our example with

Alice’s blog, HTML authors will predominantly use a single

vocabulary. On the other hand, while generating full URLs via

a CMS system is not a particular problem, typing these by hand

may be error prone and tedious for humans. To alleviate this

problem RDFa introduces the vocab attribute to

let the author declare a single vocabulary for a chunk of

HTML. Thus, instead of:

<html>

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/created" content="2011-09-10" />

<meta property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject" content="photography" />

...

</head>

...

Alice can write:

<html vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="created" content="2011-09-10" />

<meta property="subject" content="photography" />

...

</head>

...

Note how the property values are single “terms” now; these

are simply concatenated to the URL defined via the vocab

attribute. The attribute can be placed on any HTML element

(i.e., not only on the html element like in the

example) and its effect is valid for all the elements below

that point.

Default vocabularies and full URIs can be mixed at any time.

I.e., Alice could have written:

<html vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="created" content="2011-09-10" />

<meta property="http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject" content="photography" />

...

</head>

...

Perhaps a more interesting example is the combination of the

header with the licensing segment of her web page:

<html vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="created" content="2011-09-10" />

<meta property="subject" content="photography" />

...

</head>

<body>

...

<p>All content on this site is licensed under

<a property="http://creativecommons.org/ns#license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/">

a Creative Commons License</a>.</p>

</body>

</html>

The full URL for the license term is necessary to avoid

mixing vocabularies. Of course, Alice could have also written:

<html vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="created" content="2011-09-10" />

<meta property="subject" content="photography" />

...

</head>

<body>

...

<p vocab="http://creativecommons.org/ns#">All content on this site is licensed under

<a property="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/">

a Creative Commons License</a>.</p>

</body>

</html>

because the vocab in the license paragraph

overrides the definition inherited from the top of the

document.

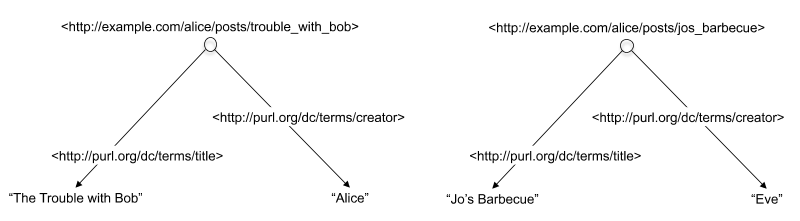

2.5 Multiple Items per Page

Alice’s blog contains, of course, multiple entries.

Sometimes, Alice’s sister Eve guest blogs, too. The front page

of the blog lists the 10 most recent entries, each with its

own title, author, and introductory paragraph. How, then,

should Alice mark up the title of each of these entries

individually even though they all appear within the same web

page? RDFa provides about, an attribute for

specifying the exact URL to which the contained RDFa markup

applies:

<div vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<div about="/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob">

<h2 property="title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 property="creator">Alice</h3>

...

</div>

<div about="/alice/posts/jos_barbecue">

<h2 property="title">Jo's Barbecue</h2>

<h3 property="creator">Eve</h3>

...

</div>

...

</div>

(Note that we used relative URLs in the example; the value of

about could have been any URLs,

relative or absolute.) We can represent this, once again, as a

diagram connecting URLs to properties:

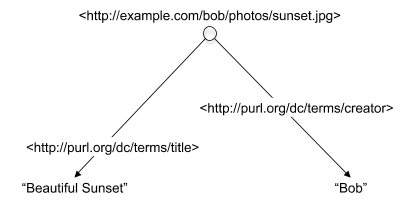

Alice can use the same technique to give her friend Bob

proper credit when she posts one of his photos:

<div about="/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob">

<h2 property="title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

The trouble with Bob is that he takes much better photos than I do:

<div about="http://example.com/bob/photos/sunset.jpg">

<img src="http://example.com/bob/photos/sunset.jpg" />

<span property="title">Beautiful Sunset</span>

by <span property="creator">Bob</span>.

</div>

</div>

Notice how the innermost about value, http://example.com/bob/photos/sunset.jpg,

“overrides” the outer value /alice/posts/trouble_with_bob

for all markup inside the innermost div. And,

once again, here is a diagram that abstractly represents the

underlying data of this new portion of markup:

3. Going Deeper

3.1 Contact Information

Alice would also like to make information about herself,

such as her email address, phone number, and other details,

easily available to her friends’ contact management software.

This time, instead of describing the properties of a web page,

she’s going to describe the properties of a person: herself.

To do this, she adds deeper structure, so that she can connect

multiple items that themselves have properties.

Alice already has contact information displayed on her blog.

<span>

Alice Birpemswick,

Email: <a href="mailto:alice@example.com">alice@example.com</a>,

Phone: <a href="tel:+1-617-555-7332">+1 617.555.7332</a>

</span>

The Dublin Core vocabulary does not provide property names

for describing contact information, but the Friend-of-a-Friend

[FOAF] vocabulary does. Alice decides to use the FOAF

vocabulary and declares a FOAF “Person”. For this purpose,

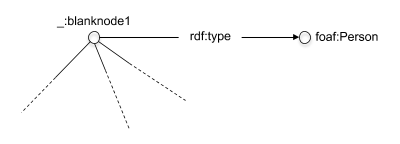

Alice uses typeof, an RDFa attribute that is

specifically meant to declare a new data item with a certain

type:

<span typeof="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person">

...

Alice realizes that she only intends to use the FOAF

vocabulary at this point, so she uses the vocab

attribute to further simplify her markup (and overriding the

effects of any vocab attributes that may have

been used in, for example, the html element at

the top).

<span vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" typeof="Person">

...

Then, Alice indicates which content on the page represents

her full name, email address, and phone number:

<span vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Alice Birpemswick</span>,

Email: <a property="mbox" href="mailto:alice@example.com">alice@example.com</a>,

Phone: <a property="phone" href="tel:+1-617-555-7332">+1 617.555.7332</a>

</span>

Note how Alice did not specify about like she

did when adding blog entry metadata. If she is not declaring

what she is talking about, how does the RDFa Processor know

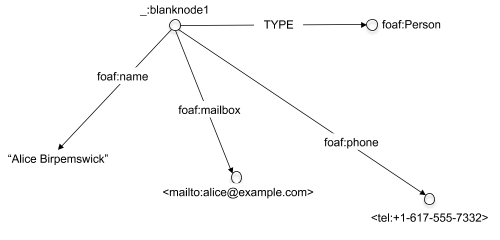

what she’s identifying? In RDFa, in the absence of an about attribute, the typeof

attribute on the enclosing div implicitly sets

the subject of the properties marked up within that div.

That is, the name, email address, and phone number are

associated with a new node of type Person. This

node has no URL to identify it, so it is called a blank

node as shown on the figure:

Of course, Alice could also decide to use a real URI for

herself instead of a blank node. Adding an about

attribute would do just that:

<span vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" about="#me" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Alice Birpemswick</span>,

Email: <a property="mbox" href="mailto:alice@example.com">alice@example.com</a>,

Phone: <a property="phone" href="tel:+1-617-555-7332">+1 617.555.7332</a>

</span>

It is considered as a good practice to use real URIs whenever possible, i.e., Alice’s second alternative

should be preferred. If a real URI is used, then it becomes possible to unambigously refer to that particular

node, whereas that becomes much more complicated with blank nodes.

The about="#me" markup is a FOAF

convention: the URL that represents the person Alice

is http://example.com/alice#me. It should not be

confused with Alice’s homepage, http://example.com/alice.

3.2 Describing Social Networks

Alice continues to mark up her page by adding information

about her friends, including at least their names and

homepages. She starts with plain old HTML:

<div>

<ul>

<li>

<a href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

First, Alice indicates that the friends she is describing are

people, as opposed to animals or imaginary friends, by using

the type Person in typeof

attributes.

<div vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<ul>

<li typeof="Person">

<a href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Beyond declaring the type of data we are dealing with, each typeof

creates a new blank node with its own distinct properties, all

without having to provide URL identifiers. Thus, Alice can

easily indicate each friend’s homepage:

<div vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<ul>

<li typeof="Person">

<a property="homepage" href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a property="homepage" href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a property="homepage" href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Alice would also like to improve the markup by expressing each person’s name using

RDFa, too. However, the property attribute cannot be used for this purpose; indeed,

property is automatically associated with href in this case. Instead,

Alice can use the rel attribute. This attribute will pick up the value of

href and, in the presence of rel, property will

use the textual content of the element instead. I.e., Alice can write:

<div vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<ul>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/bob/" property="name">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/eve/" property="name">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/manu/" property="name">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Using property, Alice has specified that the

linked text (“Bob”, “Eve”, and “Manu”) are her friends’ names; with rel;

with rel, she indicates that the clickable links

are her friends’ homepages. She could not have used rel

to be associated with the linked text; this attribute can be used

exclusively with links like the one in the href attribute.

Note that rel can be used at any time, not only in association with property.

It can also be used instead of property when used with href; i.e.,

the example above, without the linked texts, could have been written as:

<div vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<ul>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Alice is happy that, with so

little additional markup, she’s able to fully express both a

pleasant human-readable page and a machine-readable dataset.

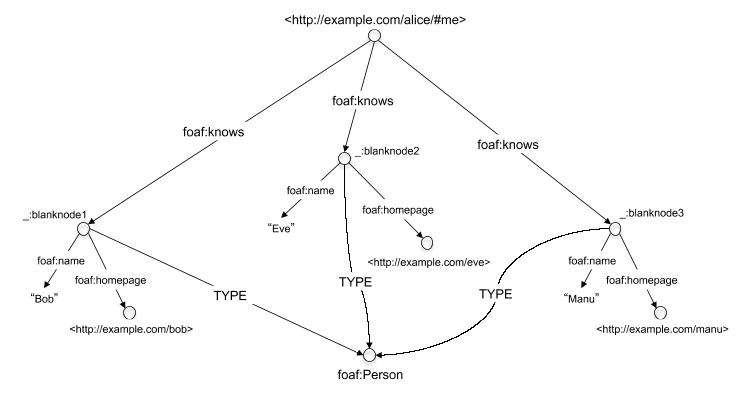

Alice is a member of 5 different social networking sites.

She is tired of repeatedly entering information about her

friends in each new social networking site, so she decides to

list her friends in one place—on her website. With RDFa, she

can indicate her friendships on her own web page and let

social networking sites read it automatically. So far, Alice

has listed three individuals but has not specified her

relationship with them; they might be her friends, or they

might be her favorite 17th century poets. To indicate that she

knows them, she uses the FOAF property foaf:knows:

<div vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" about="#me" >

<ul>

<li property="knows" typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/bob" property="name">Bob</a>

</li>

<li property="knows" typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/eve" property="name">Eve</a>

</li>

<li property="knows" typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/manu" property="name">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

With this, Alice could describe here social network:

Note that Alice had to repeat the property="knows". When there are only a few persons in her

social network, that may be fine, but it might become error prone in some other cases: she may forget to

add that attribute. An alternative is to use the rel attribute instead. In most of the

cases rel has a similar behavior to property, but it also has the concept of

chaining that can be used as follows:

<div vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" about="#me" rel="knows">

<ul>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/bob" property="name">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/eve" property="name">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="Person">

<a rel="homepage" href="http://example.com/manu" property="name">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Using rel="knows" once at the

top-most div is enough to connect Bob, Eve, and

Manu to Alice. This is achieved thanks

chaining: because the top-level rel is

without a corresponding href, it connects to any

contained node. In this case the three nodes defined by typeof.

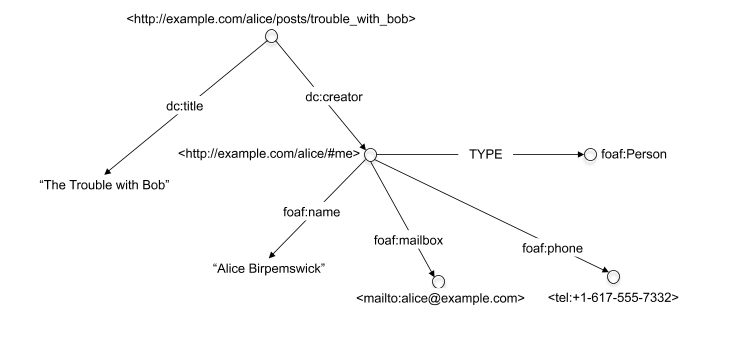

3.3 Internal References

Alice may want to add her personal data to her individual

blog items, too. She decides to combine her FOAF data with the

blog items, i.e.:

<div vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<div about="/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob">

<h2 property="title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 rel="creator">

<span vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" about="#me" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Alice Birpemswick</span>,

Email: <a rel="mbox" href="mailto:alice@example.com">alice@example.com</a>,

Phone: <a rel="phone" href="tel:+1-617-555-7332">+1 617.555.7332</a>

</span>

</h3>

...

</div>

...

</div>

Note the usage of the rel attribute instead of

property for the Dublin Core creator

term; this is because the data now involves more than just a

simple text. The structured data she generates looks like

this:

Unfortunately, this solution is not optimal. Indeed, Alice

would like to design her Web page so that her personal data

would not appear on the page in each individual blog item but,

rather, in one place like a footnote or a sidebar. What she

would like to see is something like:

If the FOAF data is included into each blog item, Alice would

have to create a complex set of CSS rules to achieve the

visual effect she wants. Instead, Alice decides to use another

RDFa attribute, namely resource:

<div vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<div about="/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob">

<h2 property="title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 rel="creator" resource="#me">Alice</h3>

...

</div>

</div>

...

<div class="sidebar">

...

<span vocab="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" about="#me" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Alice Birpemswick</span>,

Email: <a rel="mbox" href="mailto:alice@example.com">alice@example.com</a>,

Phone: <a rel="phone" href="tel:+1-617-555-7332">+1 617.555.7332</a>

</span>

</div>

The resource attribute plays exactly the same role as href

but does not provide a clickable link to the browser like href

does. Also, resource can be used on any

HTML element, in contrast to href. In this case,

usage of this attribute allows Alice to “distribute” the

various parts of the structured data on her page, although the

data itself is identical to the one on the previous example,

shown on Figure 8.

3.4 Using Multiple Vocabularies

The previous examples show that, for more complex cases,

multiple vocabularies have to be used to express the various

aspects of structured data. We have seen Alice using the

Dublin Core, as well as the FOAF and the Creative Commons

vocabularies, but there may be more. For example:

- She plans to install a plugin into her blog software so

that her social networking site’s “Like” button appears at

the bottom of each of her posts. In order to give her social

networking site information about her blog posts’ title,

thumbnail, and content type, she may want to use the Open

Graph Protocol [OGP] vocabulary to mark up her content.

- She may want to add more information on her blog, to make

use of specialized

engines that can process the SIOC

(Semantically-Interlinked Online Communities) vocabulary

[SIOC], a vocabulary that has been developed for the

Social Web.

Of course, Alice can use either full URLs for all the terms,

or can use the vocab attribute to abbreviate the

terms for the predominant vocabulary. But, in some cases, the

vocabularies cannot be separated easily, which means that vocab

may not solve all the problems. Here is, for example, the type

of HTML she might end up with:

<html vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="http://ogp.me/ns#title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="http://ogp.me/ns#type" content="text" />

<meta property="http://ogp.me/ns#image" content="http://example.com/alice/bob-ugly.jpg" />

<meta property="subject" content="photography" />

<meta property="created" content="2011-09-10" />

...

</head>

<body>

<div typeof="http://rdfs.org/sioc/ns#Post">

<h2 property="title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 property="creator">Alice</h3>

<p property="http://rdfs.org/sioc/ns#content">The trouble with Bob is that he takes much better photos than I do:</p>

...

</div>

...

</body>

</html>

Note that the SIOC and the Dublin Core terms are intertwined

for a specific blog, and it becomes an arbitrary choice to use

vocab for http://purl.org/dc/terms/

or for http://rdfs.org/sioc/ns#. The same holds

for the header, which contains both Dublin Core and Open Graph

Protocol terms.

To alleviate this problem, RDFa offers the possibility of using prefixed

terms: a special prefix attribute can assign

prefixes to represent URLs and, using those prefixes, the

vocabulary elements themselves can be abbreviated. The prefix:reference

syntax is used: the URL associated with prefix

is simply concatenated to reference to create a

full URL. Here is how the HTML of the previous example looks

like when prefixes are used:

<html prefix="dc: http://purl.org/dc/terms/ sioc: http://rdfs.org/sioc/ns# og: http://ogp.me/ns#" >

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="og:title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="og:type" content="text" />

<meta property="og:image" content="http://example.com/alice/bob-ugly.jpg" />

<meta property="dc:subject" content="photography" />

<meta property="dc:created" content="2011-09-10" />

...

</head>

<body>

<div typeof="sioc:Post">

<h2 property="dc:title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 property="dc:creator">Alice</h3>

<p property="sioc:content">The trouble with Bob is that he takes much better photos than I do:</p>

...

</div>

</body>

</html>

The usage of prefixes can greatly reduce possible errors by

concentrating the vocabulary choices to one place in the code.

Just like vocab, the prefix

attribute can appear anywhere in the HTML file, only affecting

the elements below. prefix and vocab can also be mixed, for example:

<html vocab="http://purl.org/dc/terms/" prefix="sioc: http://rdfs.org/sioc/ns# og: http://ogp.me/ns#" >

<head>

<title>The Trouble with Bob</title>

<meta property="og:title" content="The Trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="og:type" content="text" />

<meta property="og:image" content="http://example.com/alice/bob-ugly.jpg" />

<meta property="subject" content="photography" />

<meta property="created" content="2011-09-10" />

...

</head>

<body>

<div typeof="sioc:Post">

<h2 property="dc:title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 property="creator">Alice</h3>

<p property="sioc:content">The trouble with Bob is that he takes much better photos than I do:</p>

...

</div>

</body>

</html>

An important issue may arise if the html

element contains a large number of prefix declarations. The

character encoding (i.e., UTF-8, UTF-16, ascii, etc.) used for an HTML5 file is declared using a meta

element in the header. In HTML5 this meta declaration must

fall within the first 512 bytes of the page, or the HTML5

processor (browser, parser, etc.) will try to detect the

encoding some using heuristics. A very “long” html

tag may therefore lead to problems. One way of avoiding the

issue is to place most of the prefix declarations on the body

element.

3.4.1 Default Prefixes (Initial Context)

A number of vocabularies

are very widely used by the Web community with well-known prefixes—the Dublin Core

vocabulary is a good example. These common vocabularies tend

to be defined over and over again, and sometimes Web page

authors forget to declare them altogether.

To alleviate this issue, RDFa 1.1 has the concept of an initial

context that defined a set of default prefixes.

These prefixes, whose list is maintained and regularly updated (i.e., new prefixes added) by the W3C,

provide a number of pre-defined prefixes that are known to

the RDFa processor. Prefix declarations in a document always

override declarations made through the defaults, but if a

web page author forgets to declare a common vocabulary such

as Dublin Core or FOAF, the RDFa Processor will fall back to

those. The list of default prefixes are, of course,

available on the Web for everyone to read.

For example, the following example does not

declare the dc: prefix using a prefix

attribute:

<html>

<head>

<meta property="dc:title" content="The trouble with Bob" />

<meta property="dc:created" content="2011-09-10" />

...

</head

...

</html>

However, an RDFa processor still recognizes the dc:title

and dc:creator short-hands and expands the

values to the corresponding URLs. The RDFa processor is able

to do this because the dc prefix is part of

the default prefixes in the initial

http://www.w3.org/2011/rdfa-context/rdfa-1.1

context.

Default prefixes are used as a mechanism to

correct RDFa documents where authors accidentally forgot to

declare common prefixes. While authors may rely on these

to be available for RDFa 1.1 documents, the

prefixes may change over the course of 5-10 years, although

the policy of W3C is that once a prefix is defined as part

of a default profile, that particular prefix will not

be changed or removed. Nevertheless, the best way to ensure

that the prefixes that document authors use always map to

the intent of the author is to use the prefix

attribute to declare these prefixes.

Since default prefixes are meant to be a last-resort

mechanism to help novice document authors, the markup above

is not recommended. The rest of this document will utilize

authoring best practices by declaring all prefixes in order

to make the document author’s intentions explicit.

5. Some More Advanced RDFa Examples

This section contains a set of more advanced RDFa examples.

They are provided to help the reader understand a few more RDFa

usage patterns. Many of these examples describe not only how to

encode data into RDF but also what an application might try to

do with the data. Note that the implementation of those examples

may require programmatic access to the RDFa content.

5.1 Importing Data

Amy has enriched her band’s web-site to include event

information. Google Rich Snippets are used to mark up

information for search engines to use when displaying enhanced

search results. Amy also uses some JavaScript code that automatically extracts the event

information from a page and adds an entry into a personal

calendar.

Brian finds Amy’s web-site through Google and opens the

band’s page. He decides that he wants to go to the next

concert. Brian is able to add the details to his calendar by

clicking on the link that is automatically generated by the

JavaScript tool. The JavaScript extracts the RDFa from the web

page using, and places the event into

Brian's personal calendaring software—Google Calendar. Amy

automatically extracts

the event information from a page and adds an entry into

her personal calendar using some JavaScript code.

<div vocab="http://rdf.data-vocabulary.org/#" typeof="Event">

<a rel="url" href="http://amyandtheredfoxies.example.com/events"

property="summary">Tour Info: Amy And The Red Foxies</a>

<span property="location" typeof="Organization">

<a property="url" href="http://www.kammgarn.de/"><span property="name">Kammgarn</span></a>

</span>

<div><img property="photo" src="foxies.jpg"/></div>

<span property="summary">Hey K-Town, Amy And The Red Foxies will rock Kammgarn in October.</span>

When:

<span property="startDate" content="2009-10-15T19:00">15. Oct., 7:00 pm</span>-

<span property="endDate" content="2009-10-15T21:00">9:00 pm</span>

Category: <span property="eventType">concert</span>

</div>

Note that this example also uses the src

attribute; just href is recognized by RDFa, so

is src. The example relates, via a link with

“flavor” to the image whose URL is foxies.jpg. Note also that, when using rel and property

on the same element, property is used to generate a literal object, whereas the rel is used to add

the “flavor” to the link. Finally, the example makes use of the fact that property (or rel),

when used with typeof, creates a blank node that becomes the subject for the statements in the subtree.

5.2 Automatic Summaries

Mary is responsible for keeping the projects section of her

company’s home page up-to-date. She wants to display

info-boxes that summarize details about the members associated

with each project. The information should appear when hovering

the mouse over the link to each member's homepage. Since each

member’s homepage is annotated with RDFa, Mary writes a script

that requests the page’s content and extracts necessary

information via the RDFa API.

To use unique identification for the different interest

areas, Mary decides to use URLs rather than simple text. She

chooses to use the terms defined by DBpedia.

DBPedia is a dump of Wikipedia data that is expressed as a

vocabulary. It is widely used on the Semantic Web for

identifying concepts in the human world. The usage of the resource

allows her to add a reference to the human readable version of

the interest page on Wikipedia. Indeed, since both the resource

and the href attributes may appear on the same

element, the former takes precedence in RDFa while the latter

can be used to re-direct the person viewing the page to a

human-readable form of the DBPedia entry. Finally Mary uses

an RDFa script to extract this kind of information

from the HTML source in order to populate the infoboxes.

<div prefix="dc: http://purl.org/dc/terms/ foaf: http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/"

about="#me" typeof="foaf:Person">

<span property="foaf:name" content="Bob">My</span> interests are:

<ol about="#me" typeof="foaf:Person" rel="foaf:interest">

<li><a resource="http://dbpedia.org/resource/Semantic_Web"

href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantic_Web">

<span property="dc:title">Semantic Web</span>

</a>

</li>

<li><a resource="http://dbpedia.org/resource/Facebook"

href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Facebook">

<span property="dc:title">Facebook</span>

</a>

</li>

<li><a resource="http://dbpedia.org/resource/Twitter"

href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twitter">

<span property="dc:title">Twitter</span>

</a>

</li>

</ol>

</div>

Mary also uses the chaining, via the rel attribute, to avoid repeating that attribute on

all the entry on her interests and to set the right subject for the textual explanation of those.

5.3 Address Visualization

Richard has created a site that lists his favorite

restaurants and their locations. He doesn’t want to generate

code specific to the various mapping services on the Web.

Instead of creating specific markup for Yahoo Maps, Google

Maps, MapQuest, and Google Earth, he instead adds address

information via RDFa to each restaurant entry. This enables

him to build a general tool that extracts the address

information and access the mapping tool the user wishes.

<div vocab="http://www.w3.org/2006/vcard/ns#" typeof="VCard">

<span property="fn">Wong Kei</span>

<span property="street-address">41-43 Wardour Street</span>

<span property="locality">London</span>, <span property="country-name">United Kingdom</span>

<span property="tel">020 74373071</span>

</div>

5.4 Linked Data Mashups

Marie is a chemist, researching the effects of ethanol on

the spatial orientation of animals. She writes about her

research on her blog and often makes references to chemical

compounds. She would like any reference to these compounds to

automatically have a picture of the compound's structure shown

as a tooltip, and a link to the compound’s entry on the

National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] Web site.

Similarly, she would like visitors to be able to visualize the

chemical compound in the page using a new HTML5 canvas widget

she has found on the web that combines data from different

chemistry websites.

<div vocab="http://rdf.freebase.com/rdf/">

My latest study about the effects of

<span about="en.ethanol"

typeof="http://dbpedia.org/ontology/ChemicalCompound"

property="chemistry.chemical_compound.pubchem_id"

content="702">ethanol</span> on mice's spatial orientation show that ...

</div>

5.5 Enhanced Browser Interfaces

Dave is writing a browser plugin that filters product offers

in a web page and displays an icon to buy the product or save

it to a public wishlist. The plugin searches for any mention

of product names, thumbnails, and offered prices. The

information is listed in the URL bar as an icon, and upon

clicking the icon, displayed in a sidebar in the browser. He

can then add each item to a list that is managed by the

browser plugin and published on a wishlist website.

Because many of his pages make use of the Good Relation

ontology [GR], which is widely used to markup products, Dave

decides to make use of the vocab facility of

RDFa to simplify his code. He also forgets to declare the rdfs

prefix, but since it is defined by the RDFa default profile,

the data that he intended to express using the rdfs

prefix will still be extracted by all conforming RDFa

processors.

<div prefix="foaf: http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<div vocab="http://purl.org/goodrelations/v1#" about="#offering" typeof="Offering">

<div property="foaf:page" resource="http://www.amazon.com/Harry-Potter-Deathly-Hallows-Book/dp/0545139708"></div>

<div property="rdfs:label">Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows</div>

<div property="rdfs:comment">In this final, seventh installment of the Harry Potter series, J.K. Rowling

unveils in spectactular fashion the answers to the many questions that have been so eagerly

awaited. The spellbinding, richly woven narrative, which plunges, twists and turns at a

breathtaking pace, confirms the author as a mistress of storytelling, whose books will be read,

reread and read again.</div>

<div>

<img property="foaf:depiction" src="http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51ynI7I-qnL._SL500_AA300_.jpg" />

</div>

<div property="hasBusinessFunction" resource=http://purl.org/goodrelations/v1#Sell"></div>

<div property="hasPriceSpecification" typeof="UnitPriceSpecification">Buy for

<span property="hasCurrency" content="USD">$</span>

<span property="hasCurrencyValue">7.49</span>

</div> Pay via:

<span property="acceptedPaymentMethods" resource="http://purl.org/goodrelations/v1#PayPal">PayPal</span>

<span property="acceptedPaymentMethods" resource="http://purl.org/goodrelations/v1#MasterCard">MasterCard</span>

</div>

</div>

</div>

5.6 Publication lists

Mark wants to publish his publication list, which contains references to articles, books, book chapters, etc.

He can use the Bibliographic Ontology [BIBO] for that purpose. However, the problem he has is that many of his

publications have co-authors and, in the publication world, the order of the authors in a citation is

important.

Mark can use the inlist feature of RDFa. Using this feature guarantees that the order of the

resources, as they appear in the HTML text, is preserved in terms of structured data, too:

<p prefix="bibo: http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/ dc: http://purl.org/dc/terms/ typeof="bibo:Chapter">

“<span property="dc:title">Semantic Annotation and Retrieval</span>”, by

<span inlist property="dc:creator">Ben Adida</span>,

<span inlist property="dc:creator">Mark Birbeck</span>, and

<span inlist property="dc:creator">Ivan Herman</span>.

</p>

6. You Said Something about RDF?

RDF, the Resource Description Framework, is the abstract data

representation we have drawn out as graphs in the examples

above. Each arrow in the graph is represented as a

subject-property-object triple: the subject is the node at the

start of the arrow, the property is the arrow itself, and the

object is the node or literal at the end of the arrow. A set of

such RDF triples is often called an “RDF graph”, and is

typically stored in what is often called a “Triple Store” or a

“Graph Store”.

Consider the first example graph:

The three RDF triples for this graph are written, using the

Turtle syntax [TURTLE], as follows:

<http://www.example.com/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob>

<http://purl.org/dc/terms/title> "The Trouble with Bob" ;

<http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject> "photography" ;

<http://purl.org/dc/terms/created> "2011-09-10" .

Also, the TYPE arrows we drew are no

different from other arrows. The TYPE is just

another property that happens to be a core RDF property, namely

rdf:type. The rdf vocabulary is

located at http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns.

The contact information example from above should thus be

diagrammed as:

The point of RDF is to provide a universal language for

expressing data. A unit of data can have any number of

properties that are expressed as URLs. These URLs can be reused

by any publisher, much like any web publisher can link to any

web page, even ones they did not create themselves. Given data,

in the form of RDF triples, collected from various locations,

and using the RDF query language SPARQL [RDF-SPARQL-QUERY],

one can search for “friends of Alice’s who created items whose

title contains the word ‘Bob’,” whether those items are blog

posts, videos, calendar events, or other data types.

RDF is an abstract data model meant to maximize the reuse of

vocabularies. RDFa is a way to express RDF data within HTML, in

a way that is machine-readable, and by reusing the existing

human-readable data in the document.

6.1 Custom Vocabularies

As Alice marks up her page with RDFa, she may discover the

need to express data, such as her favorite photos, that is not

covered by existing vocabularies. If she needs to, Alice can

create a custom vocabulary suited for her needs. Once a

vocabulary is created, it can be used in RDFa markup like any

other vocabulary.

The instructions on how to create a vocabulary, also known

as an RDF Schema, are available in Section 5 of the RDF Primer

[RDF-SCHEMA]. At a high level, the creation of a vocabulary

for RDFa involves:

- Selecting a URL where the vocabulary will reside, for

example:

http://example.com/photos/vocab#.

- Publishing the vocabulary document at the specified

vocabulary URL. The vocabulary document defines the classes

and properties that make up the vocabulary. For example,

Alice may want to define the classes

Photo and

Camera, as well as the property takenWith

that relates a photo to the camera with which it was taken.

- Using the vocabulary in an HTML document either with the

vocab

attribute or with the prefix declaration mechanism. For

example: prefix="photo:

http://example.com/photos/vocab#" and typeof="photo:Camera".

It is worth noting that anyone who can publish a document on

the Web can publish a vocabulary and thus define new data

fields they may wish to express. RDF and RDFa allow fully

distributed extensibility of vocabularies.