1 Introduction

It is common to say things like "the title of http://example/hen is 'Trouvée'", or, in a machine-readable language such as Turtle,

<http://example/hen> dc:title "Trouvée".with the intent of saying something about what you get from dereferencing the URI 'http://example/hen'. This manner of speaking is mysterious in two ways. First, dereferencing this URI might yield different results at different times or at the same time to different clients. There may be differences in layout, format, or content as the host improves its site or adapts to client preferences. Because there is variability in what you get, it may be that some results may have that title, while others don't. Is this a problem? If not, why not?

Second, the statement suggests that there is something that has that title - a thing that the URI refers to. What is the nature of that thing and what can we say about it? Is it some particular dereference result, or some other kind of entity that is somehow related to all dereference results?

This note is a post hoc rational reconstruction of Web metadata intended to answer these questions. It proceeds in three stages. First, the idea of generic entities that have metadata is introduced, without any particular reference to the Web. Second, it is suggested that there are generic entities on the Web associated with URIs. Third, it is suggested that while these entities are fundamentally independent of their names, it is useful to name them using the URIs with which they're associated, as opposed to some other kind of name.

We are using "Web metadata" as a shorthand to describe a particular situation. There is much metadata on the Web for which attention to complications introduced by URI dereference is not relevant, including embedded metadata (e.g. XMP) and traditional bibliographic records. These other aspects of metadata on the Web will not be covered in this note.

2 Generic metadata

Metadata is data about data or information about information.[1] Typical metadata includes information about some information entity's content (title, word count, topic, format, language, etc.) and provenance (author, publisher, publication date, revision history, etc.).[2] Because metadata is information about information, it might be stated of any kind of information entity, such as a document, image, or audio recording.

The same metadata may apply to multiple information entities, as when an HTML document and a PDF document both have the same title, author, date, word count, topic, and so on as a consequence of having been generated from a common source. It will be useful to have a term to apply in the situation where metadata does not explicitly specify a particular subject, so define a "metadata predicate" to be metadata of this sort.[3] In this case we would have a metadata predicate that is true of documents that have a particular title, author, and so on (whatever is common to the HTML and PDF versions), while the metadata predicate "is an HTML document" would be true of one format but not the other.

The situation where collections of information entities are related to one another in some way (e.g. via revision, translation, or reformatting) is quite common. People often play a grammatical trick in this situation, where a class of related entities is treated as if it were a single generic entity. For a non-information example, we might say "the tapir has a prehensile snout" referring not to an individual tapir but to tapirs in general. If there were a tapir in front of us the statement would indeed be true of that specific tapir, but "the tapir" refers not to that tapir but to a "generic tapir". The generic tapir might be said to "generalize" the specific one.

Similarly, if we say "Elizabeth Bishop wrote that poem about a hen" then "that poem about a hen" refers not to some particular information entity with a definite length, layout, and format, but to a class of information entities that have in common, among other things, that they're by Elizabeth Bishop and are poems. The specific entity that I read and the one that you read may differ, but if so it will be in ways that are not important to what we're talking about. (See [GR].)

The reason we consider these generic entities to exist is so that we can say things about them as if they were specific - i.e. so that we can apply predicates to them - and avoid the need to express a universal quantification ("every tapir") explicitly. A metadata predicate therefore holds of a generic information entity when, and only when, it holds of the information entities that the generic entity generalizes.

Put formally, if M[] is a metadata predicate and G is a generic information entity,

-

M[G] if and only if {M[S] for all S such that G generalizes S}.

3 Web metadata

We now relate this idea to the Web. The Web works as follows: A set of governing specifications ([3986], etc.) and namespaces (e.g. DNS) "authorize" servers and APIs to yield certain "representations"[4] (specific information entities) in response to requests to dereference a given URI. Let's say that in this situation a representation is "authorized for" the URI. This formulation is neutral with regard to protocol, but HTTP is an important point of reference: With a properly functioning infrastructure, an HTTP request GET U will yield a 200 OK response carrying representation Z only when Z is authorized for U.

When only one representation is authorized for a URI, a server, cache, or API will yield that representation (or fail to yield any). The set of authorized representations may vary over time. Application scenarios in which multiple representations are authorized at one time for a single URI include content negotiation variants (such as versions in multiple language), representations that vary depending on user identity or session state, or overlapping cache lifetimes (Expires:) for different versions of a changing document.

We can say that "information resource" (the conventional term in Web architecture) is a near-synonym for "generic information entity" as above, with the possibility understood that in some cases an information resource will have only one specialization.[5] The following defines what it means for an information resource to be "on the Web" at a given URI:

-

G is "on the Web" at U means that U's authorized representations

are exactly those representations that G generalizes.[6]

We take as axiomatic that for any nonempty class of representations there is an information resource that generalizes those and only those representations. This lets us say:

-

For any URI U having authorized representations, there is an

information resource G such that G is on the Web at U.

Now where does this get us? To say that any representation retrieved from "http://example/hen" has (or will have) "Trouvée" as its title, we can write (in Turtle [turtle])

[ir:onWebAt "http://example/hen"] dc:title "Trouvée".(where ir:onWebAt is the name for the "on the Web at" property in some yet-to-be-standardized vocabulary). This is a useful thing to say, since it is predictive: It tells someone that if they dereference that URI, they will get something with that dc:title. They may not see the exact same representation that the agent who wrote the metadata saw, but it will be close enough that the metadata still applies.

The agent that authorizes representations for a URI is in a good position to write metadata relating to that URI, since they can ensure that the metadata is true for any representation they authorize. On the other hand, other agents can be correct in writing metadata, if they know something about how the controlling agent manages its namespace (web site). Guaranteed correctness is not always necessary, however, and metadata may just express a reasonable or useful belief. One can be confident when there is a credible and irrevocable public commitment regarding authorized representations, as there is for, say, the data: URI scheme, but the representations authorized for http: scheme URIs, as the http: scheme is currently formulated, ultimately depend on those institutions such as ICANN that in practice control domain names, making such all statements of metadata contingent.[7]

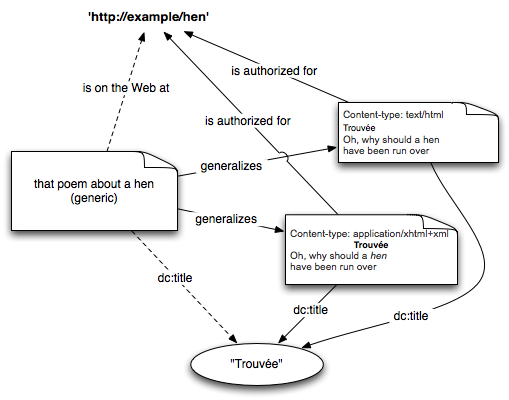

The following diagram illustrates the various entities involved and their relationships. Dashed lines indicate relationships that are equivalent to universally quantified statements.

4 Naming information resources

A common practice is to use an absolute URI as a name for an information resource that is on the Web at that URI. This practice is parsimonious: It would be more complicated than necessary for a single URI to be used on the Web in one way, and to name in another way. If this is done for the above example, we would write

<http://example/hen> dc:title "Trouvée".to give the title of the information resource on the Web at 'http://example/hen'. Because using URIs like this is common — some might say obvious — practice, such a statement is often understood, without further explanation, as saying something about representations retrieved using the given URI.

However, use of URIs in this way is not a foregone conclusion. Should there be any doubt as to whether the URI will be understood in this way, one might write

<http://example/hen> ir:onWebAt "http://example/hen".

<http://example/hen> dc:title "Trouvée".to be explicit about what one means.

In the event that the URI is unavailable to name the information resource because it is already used to name something else, then some other name can be used to refer to an information resource on the Web at that URI. In Turtle, this could be blank node notation such as [ir:onWebAt "http://example/hen"], or a different URI:

:poem ir:onWebAt "http://example/hen".

:poem dc:title "Trouvée".Whether we can expect in general that a dereferenceable URI will be understood as a name for an information resource on the Web at that URI is the essence of the heated httpRange-14 debate [issue-14], which is essentially a turf war over use of the URI namespace. Those who consider it important to write Web metadata have an interest in the manner described above, since it gives obvious names to entities on the Web and therefore an easy way to say things about them.[8] Those who don't care about talking about the Web in this way may see an opportunity to put the URIs in question to uses better suited to their applications. If the httpRange-14 rule is not generally respected, then the meaning of all dereferenceable URIs will be put in doubt, and new notational conventions for metadata similar to the above constructions using ir:onWebAt will have to be instituted for use in potentially all Web metadata.

5 References

- issue-57

- Issue-57: Mechanisms for obtaining information about the meaning of a given URI. W3C Technical Architecture Group, 2007-2011. (See http://www.w3.org/2001/tag/group/track/issues/57.)

- GR

- Tim Berners-Lee. Generic resources. Design note, 2006-2009. (See http://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/Generic.html.)

- 3986

- T. Berners-Lee, R. Fielding, L. Masinter. Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Generic Syntax. RFC 3986, IETF, 2005. (See http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3986.txt.)

- webarch

- Ian Jacobs and Norman Walsh, editors. Architecture of the World Wide Web, Volume One. W3C Recommendation, December 2004. (See http://www.w3.org/TR/webarch/.)

- turtle

- David Beckett and Tim Berners-Lee. Turtle - Terse RDF Triple Language. W3C Team Submission, 2011. (See http://www.w3.org/TeamSubmission/2011/SUBM-turtle-20110328/.)

- issue-14

- Issue-14: What is the range of the HTTP dereference function? W3C Technical Architecture Group, 2002-2005. (See http://www.w3.org/2001/tag/group/track/issues/14.)

- issue-14-resolved

- Roy Fielding. [httpRange-14] Resolved. Email to www-tag list, 2005. (See http://lists.w3.org/Archives/Public/www-tag/2005Jun/0039.html.)