More about the document head

Introduction

In The HTML <head> element article of this course we learned about the essential things that go inside the head of an HTML document. In this article of the Web Standards Curriculum we’ll expand on that information and talk about some other — lesser used — things that you can add to the head section of an HTML document; these are less essential, but still very useful nonetheless. By the end of this tutorial you’ll know how to collate several HTML documents into a larger multi-part collection, what a favicon is and how to use it, and what RSS is all about. Before you go any further, download this article’s accompanying zip file so you can follow along with the examples.

Document relationships — collating several HTML documents into a collection

One feature of HTML that stems from the origins of the web as a document repository are document relationships. These define how one document relates to another, for example if it is the previous or next document in a logical chain or if it is the index of a whole series of documents.

In a sense, you’ve already done this in The HTML <head> element article, when you applied a style sheet to a document to give it a different look and feel with the link element:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en-GB"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <title>Breeding Dogs - Tips about Alsatians</title> <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" media="screen" href="styles.css"> <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" media="print" href="printstyles.css"> </head> <body> </body> </html>

The relationship of the current document to others is defined in much the same way using the link element and the rel or rev attributes. The rel attribute (relationship) defines the relationship that the linked document has to the current one, and the rev attribute (reverse relationship) defines the relationship the current document has to the linked one.

Don’t worry about the rev attribute too much — it is a bit confusing, but you will need to use it rarely, if at all.

There are no mandatory prefixed values for the rel and rev attributes, but there is a taxonomy supported by browsers and indexing tools that you should consider following under most normal circumstances for rel:

- home: The home document of the current collection

- index: The index of the current collection

- contents: The contents list of the current collection

- search: The search page of the current collection

- glossary: The glossary of the current collection

- help: The help page of the current collection

- first: The first document in current collection

- previous: The previous document from this one in the logical order of the collection

- next: The document following this one in the logical order of the collection

- last: The last document of the current collection

- up: The document one level up in the hierarchy of the current collection

- copyright: The copyright information of the current collection

- author: The information page about the author of the current collection

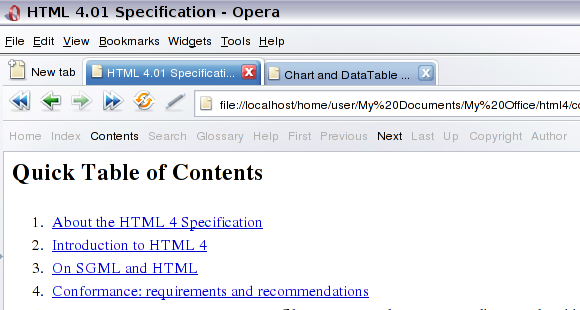

Most browsers don’t do anything with this information. Some however will follow the link and load the document in the background so that it shows up a lot faster for the reader. The real browser exception is Opera, which has an extra navigation toolbar you can turn on by selecting View > Toolbars > Navigation bar from the menu. Once turned on you get the link relationships defined in the document as an extra toolbar. Figure 1 shows the W3C HTML standards document in Opera:

Figure 1: Opera shows the link relationships of the current document in a special navigation toolbar

Even though they are not displayed in a visible sense, it is a good idea to provide a human-readable explanation of what the linked documents are about in a title attribute as the file names alone are not necessarily enough.

Now let’s move on to have a look at how link relationships can be used to collate several documents into a collection. For example, the start page of an online course spanning several documents could be the following (start.html):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Link relationship example</title>

<link rel="contents" title="table of contents" href="toc.html">

<link rel="next" title="next: chapter one" href="chapter1.html">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Course example</h1>

<p>This would be the cover page of an article series or course</p>

<ul>

<li><a href="chapter1.html" rel="next">Let's start with Chapter One</a></li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>

The first chapter would be the following (chapter1.html):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Chapter One - Link relationship example</title>

<link rel="contents" title="Table of Contents" href="toc.html">

<link rel="home" title="Home Page" href="start.html">

<link rel="prev" title="previous: Home Page" href="start.html">

<link rel="next" title="next: Second Chapter" href="chapter2.html">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Chapter One</h1>

<p>This would be the chapter one page of an article series or course</p>

<ul>

<li><a href="start.html" rel="prev">Back to Start</a></li>

<li><a href="toc.html" rel="contents">Table of contents</a></li>

<li><a href="chapter2.html" rel="next">Go on to Chapter Two</a></li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>

The second chapter (chapter2.html):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Link relationship example</title>

<link rel="contents" title="Table of Contents" href="toc.html">

<link rel="home" title="Home page" href="start.html">

<link rel="prev" title="previous: first chapter" href="chapter1.html">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Chapter Two</h1>

<p>This would be the second chapter page of an article series or course</p>

<ul>

<li><a href="chapter1.html" rel="prev">Back to chapter 1</a></li>

<li><a href="toc.html" rel="contents">Table of contents</a></li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>

And finally the table of contents (toc.html):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Table of contents - Link relationship example</title>

<link rel="home" title="home page" href="start.html">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Table of contents</h1>

<ul>

<li><a href="chapter1.html">Chapter One - about stuff</a></li>

<li><a href="chapter2.html">Chapter Two - about other stuff</a></li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li><a href="start.html" rel="home">Back to home</a></li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>

You can also use rel and rev attributes on the links in the document to tell browsers and assistive technology that these anchors correspond with the link relationships. And rel and rev are used for other purposes such as Microformats—check out this article for some uses of the XFN Microformat.

Linking to alternative versions of the document

The option to link to other documents that have a certain relationship to the document in question also includes different language versions of the same document, or different formats. You can do both by providing a link with a rel attribute value of alternate, indicating an alternative version.

Translations

Translations are a great candidate for document interlinking. It might for example be that one language version of a document is very successful and visitors who don’t speak that language would love to have that information available to them. By linking from the original to the alternative language version you’ll make it easier for readers of the alternative to understand and promote the content and possibly make the other language version as successful. The following example shows how you can define the other language versions (languageexample.html); note the syntax — it’s pretty intuitive:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Multiple Languages example</title>

<link rel="contents" title="table of contents" href="toc.html">

<link rel="next" title="next: chapter one" href="chapter1.html">

<link rel="alternate" title="The course in Dutch" type="text/html" hreflang="nl" href="../nl/start.html">

<link rel="alternate" title="The course in German" type="text/html" hreflang="de" href="../de/start.html">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Course example</h1>

<p>This would be the cover page of an article series or course</p>

<ul>

<li><a href="chapter1.html" rel="next">Let's start with Chapter One</a></li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li>Other languages:

<uL>

<li><a href="../de/start.html" lang="de" hreflang="de">Deutsch</a></li>

<li><a href="../de/start.html" lang="nl" hreflang="nl">Nederlands</a></li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>

As a recap, the hreflang attribute on links and anchors defines the human language of the linked document and the lang attribute defines the language of the text inside the element that has this attribute. This is very important for accessibility as text-to-speech software needs to switch the pronounciation voice from language to language.

Different languages have obviously been around since the Internet first existed (and thousands of years before that), but there is another type of alternative web page that you’ll see a lot as you trawl the web—feeds (eg RSS feeds). These are very popular, especially for documents that change constantly, such as news sites. We’ll look at these next.

Feeds

A feed is a document containing condensed information detailing the new additions to your site in chronological order. Users can subscribe to it and get to know what has changed on your site recently without having to visit it. They do this by using tools like feed readers, eg Google Reader, Netvibes or Bloglines. Some modern browsers (such as Opera and Firefox) and e-mail clients (such as Mac Mail, or Outlook on Windows) can also process and display feeds. You can recognize that a web site offers a feed by the RSS icon next to the location as shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Opera shows an orange RSS icon next to the location of web sites that offer a feed.

Feed pages are either structured using HTML or an XML format like RSS or Atom, and they are hardly ever generated by hand. Most of the time personal publishing systems will do that work for you and all you need to do to offer the world a feed of your site is link to the XML document with the correct meta element in the head of your document. The following is an excerpt from my blog at http://wait-till-i.com and points to the RSS feed (feedexample.html):

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en-GB"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <link rel="alternate" type="application/rss+xml" title="Wait till I come! RSS Feed" href="http://www.wait-till-i.com/feed/"> <title>Wait till I come!</title> </head> <body> <p>Example of an RSS feed</p> </body> </html>

Supplying a feed makes sense for content-heavy web sites that change very often (like blogs or photo sites), and by using a feed reading tool and subscribing to feeds you can cut down on a lot of your surfing and research time. If you don’t update your site that often but you have a lot of content and want people to have a visual reminder of your web site, then you might want to consider using a shortcut icon to stand out in people’s bookmark lists. This is what We’ll cover in the section below.

Making bookmarking more fun — using favicons

One last subject we’ll cover here is shortcut icons or favicons. These are small images with a file format of .ico — if you place one on your web server, you can use it to show a small icon next to the entry of your web site in a visitor’s bookmark list, as shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Icons next to a bookmark make it easier to remember the site. You can add one of these by using a shortcut-icon meta element.

Note that most browsers support formats other than .ico for favicons, but you should stick with .ico as IE doesn't support other favicon formats.

The biggest obstacle to adding your shortcut icon is actually creating it in the right format as not many graphics creation packages support the ico format. One option is to use the free online tool genfavicon. Once you have it, adding it to your document is as easy as adding another meta element with a rel value of “Shortcut Icon”, as shown in the following example (favicon-example.html):

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en-GB"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <title>Shortcut Icon example</title> <link rel="Shortcut Icon" href="favicon.ico" type="image/x-icon"> </head> <body> <h1>Example of a shortcut icon</h1> </body> </html>

If you open this document in a browser it should show the Opera icon next to the address in the location toolbar. If you bookmark it, the same icon will appear next to the bookmark.

Summary

That’s all for this article, and for the head section of an HTML document. There are other things we could cover, but they tend to be fairly advanced subjects, and often not a good idea — what we have covered here, and in The HTML <head> element article, should give you all you need to get on.

Exercise questions

- Why does it make sense to define link relationships when they are not displayed?

- How would you link to a search page?

- What use is offering a feed to your visitors? What

relvalue do you use to link to one? - What do you need to make sure of when you link to documents in other languages?

- If you open the example documents in a text editor you’ll find another

metaelement we haven’t discussed here with an attribute ofcontent-type, and something calledutf-8. What isutf-8?

Note: This material was originally published as part of the Opera Web Standards Curriculum, available as Supplementary: More about the document <head>, written by Christian Heilmann. Like the original, it is published under the Creative Commons Attribution, Non Commercial - Share Alike 2.5 license.

Next: The HTML body: Marking up textual content in HTML.