HTML structural elements

Introduction

Now we've gotten to grips with the very basics of HTML, what is contained inside the document <head>, and the different building blocks you'll most commonly use to structure different items of content inside the <body>, at this point in the Web Standards Curriculum we will start to look at the overall structure of the HTML content, and what distinct sections the page contains.

A typical page structure

Before you read any further, go and have a look at 5-10 of your favourite web sites. They will have vastly differing content, functionality, and look and feel, but they will all have common elements. There are very few sites that don't at least loosely follow the pattern of:

- Header (or masthead) at the top of the page, usually containing the top level heading of the page, and/or a company logo. This is the big bold statement at the top of the page that says what the web site is, and who it belongs to.

- Main content column, which holds the main content of functionality you are here to use.

- One of more sidebars, holding tributary content that is either related to that page's main content and changes as new pages are loaded (eg related links), or is always relevant and persists across the whole site (eg "your basket" information on an e-commerce site).

- Navigation menu going across the page or down the page in a column. This often put in a sidebar, or may form part of the header.

- A footer that goes across the bottom of the site and contains secondary information such as copyright information and contact details.

Lets visualise this a bit more with a specific example. The web site of Conquest of Steel (Chris Mills' band!) looks like so

Figure 1: A typical example web site.

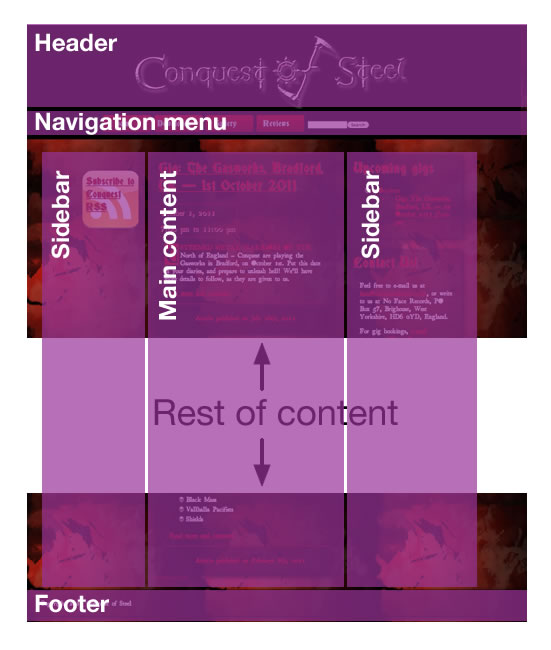

We could break this up into the sections we have just discussed, like so:

Figure 2: the example site, with distinct sections overlaid.

These sections could contain any number of different nested elements, for example a footer could include a list full of links, a couple of paragraphs and an image. But how do we mark up these distinct sections, and group them together as single entities that can be laid out later on using CSS? Lets have a look, in the next section.

Structuring a page with HTML 4

HTML4 contains two generic container elements:

- The

<div>is a block level container that you can use to group sections of block level content together. - The

<span>is an inline container that you can use to group sections of inline content together.

Note that <div> and <span> elements have no inherent content or dimensions, only that of their contents, until they are styled via CSS or manipulated by JavaScript. They also have no semantics, and the only way you can identify them is by giving them a class or id attribute.

You should only use these elements when there isn't a more appropriate, semantic element to use for marking up content. Marking up paragraphs and headings all with <div>s is a terrible thing to do, as although it might look ok, the page will be inaccessible to those using screen readers (screen readers need a good structure of headings to navigate by), plus it will be more bloated, harder to read, and less efficient to style with CSS. Try to cut down on the number of <div>s and <span>s used when possible: an abuse of these elements leads to what we call "divitis".

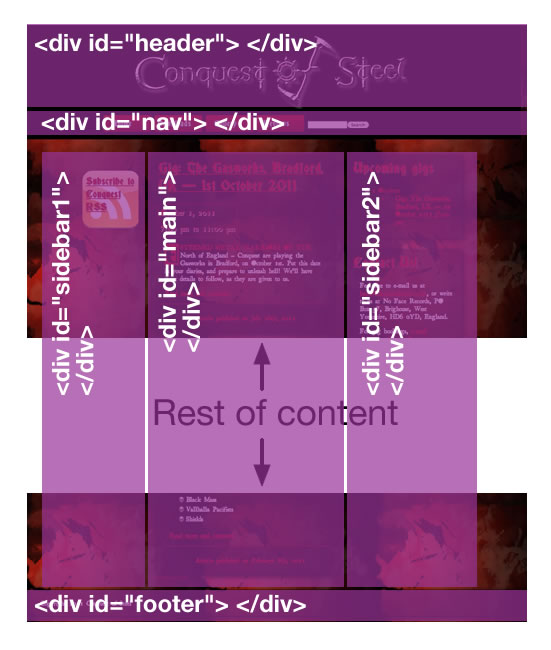

So, to mark up the example site, you could use the following elements:

Figure 3: The example site, with appropriate HTML4 elements indicated for different major structural sections.

The markup would look something like this:

<body>

<div id="header">

<!-- header content goes in here -->

</div>

<div id="nav">

<!-- navigation menu goes in here -->

</div>

<div id="sidebar1">

<!-- sidebar content goes in here -->

</div>

<div id="main">

<!-- main page content goes in here -->

</div>

<div id="sidebar2">

<!-- sidebar content goes in here -->

</div>

<div id="footer">

<!-- footer content goes in here -->

</div>

</body>

It's that simple really. Of course, it is not going to look like a properly laid out site until you apply CSS to the HTML: you will learn a lot more about this later on in the course. But it does give you the structural integrity you need to get the site laid out how you want.

Enter HTML5 structural elements

The HTML4 way of doing things is all well and good, but semantically it could be so much better:

- Humans can tell the different content apart, but machines can't — the browser doesn't see the different divs as header, footer, etc. It sees them as different divs. Wouldn't it be more useful if browsers and screen readers were able to explicitly identify say, the navigation menu so a visually impaired user could find it more easily, or the different news items on a bunch of blogs so they could be easily syndicated in an RSS feed without any extra programming?

- Even if you do use extra code to solve some of these problems, you can still only do it reliably for your web sites, as different web developers will use different class and ID names, especially when you consider the international audience — different web developers in different countries will use different languages to write their class and id names.

It therefore makes a lot of sense to define a consistent set of elements for everyone to use for the common structural blocks that appear on so many web sites, and this is exactly what is defined in HTML5.

The new HTML5 elements we will cover in this article are:

<header>: Used to contain the header content of a site.<footer>: Contains the footer content of a site.<nav>: Contains the navigation menu, or other navigation functionality for the page.<article>: Contains a standalone piece of content that would make sense if syndicated as an RSS item, for example a news item.<section>: Used to either group different articles into different purposes or subjects, or to define the different sections of a single article.<aside>: Defines a block of content that is related to the main content around it, but not central to the flow of it.

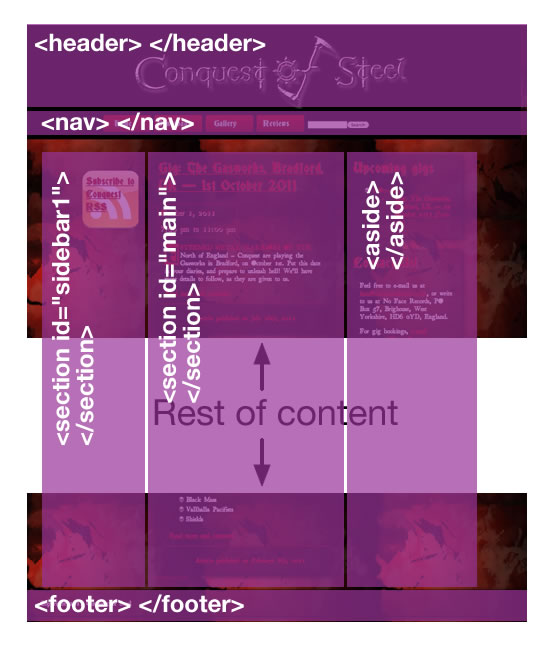

we will discuss these in more detail a little later on, but for now, let's look at how our example could look when structured using HTML5 elements:

Figure 4: The example site, with appropriate HTML5 elements indicated for different major structural sections.

In code, this looks like so:

<body>

<header>

<!-- header content goes in here -->

</header>

<nav>

<!-- navigation menu goes in here -->

</nav>

<section id="sidebar1">

<!-- sidebar content goes in here -->

</section>

<section id="main">

<!-- main page content goes in here -->

</section>

<aside>

<!-- aside content goes in here -->

</aside>

<footer>

<!-- footer content goes in here -->

</footer>

</body>

Let's explore some of the HTML5 elements in more detail.

<section>

The <section> element is for containing distinct different areas of functionality or subjects area, or breaking an article or story up into different sections. So in this case:

- "sidebar1" contains various useful links that will persist on every page of the site, such as "subscribe to RSS" and "Buy music from store".

- "main" contains the main content of this page, which is blog posts. On other pages of the site, this content will change.

It is a fairly generic element, but still has way more semantic meaning than the plain old <div>.

<article>

<article> is related to <section>, but is distinctly different. Whereas <section> is for grouping distinct sections of content or functionality, <article> is for containing related individual standalone pieces of content, such as individual blog posts, videos, images or news items. Think of it this way - if you have a number of items of content, each of which would be suitable for reading on their own, and would make sense to syndicate as separate items in an RSS feed, then <article> is suitable for marking them up.

In our example, <section id="main"> contains blog entries. Each blog entry would be suitable for syndicating as an item in an RSS feed, and would make sense when read on its own, out of context, therefore <article> is perfect for them:

<section id="main">

<article>

<!-- first blog post content goes here -->

</article>

<article>

<!-- second blog post content goes here -->

</article>

<article>

<!-- third blog post content goes here -->

</article>

</section>

Simple huh? Be aware though that you can also nest sections inside articles, where it makes sense to do so. For example, if each one of these blog posts has a consistent structure of distinct sections, then you could put sections inside your articles as well. It could look something like this:

<article> <section id="introduction"> </section> <section id="content"> </section> <section id="summary"> </section> </article>

as we already mentioned above, the purpose of the <header> and <footer> elements is to wrap header and footer content, respectively. In our particular example the <header> element contains a logo image, and the <footer> element contains a copyright notice, but you could add more elaborate content if you wished. Also note that you can have more than one header and footer on each page - as well as the top level header and footer we have just discussed, you could also have a <header> and <footer> element nested inside each <article>, in which case they would just apply to that particular article. Adding to our above example:

<article> <header> </header> <section id="introduction"> </section> <section id="content"> </section> <section id="summary"> </section> <footer> </footer> </article>

The <nav> element is for marking up the navigation links or other constructs (eg a search form) that will take you to different pages of the current site, or different areas of the current page. Other links, such as sponsored links, do not count. You can of course include headings and other structuring elements inside the <nav>, but it's not compulsory.

<aside>

you may have noticed that we used an <aside> element to markup the 2nd sidebar: the one containing latest gigs and contact details. This is perfectly appropriate, as <aside> is for marking up pieces of information that are related to the main flow, but don't fit in to it directly. And the main content in this case is all about the band!

Other good choices for an <aside> would be information about the author of the blog post(s), a band biography, or a band discography with links to buy their albums.

Where does that leave <div>?

So, with all these great new elements to use on our pages, the days of the humble <div> are numbered, surely? NO. In fact, the <div> still has a perfectly valid use. You should use it when there is no other more suitable element available for grouping an area of content, which will often be when you are purely using an element to group content together for styling/visual purposes. A common example is using a <div> to wrap all of the content on the page, and then using CSS to centre all the content in the browser window, or apply a specific background image to the whole content.

HTML5 element support

Ok, so at this point I should admit something. There is currently not much support for the HTML5 structural elements in todays' selection of web browsers. But before you go running for the hills screaming "why did he waste our time with all this rubbish??", just sit back and hear what I have to say. Yes, lack of support for these features across browsers is less than ideal, but in fact it doesn't really matter for our purposes very much.

The way that the elements work in general between HTML 4 and HTML 5 is exactly the same - it is just the element names that are different. As you have seen above, it is easy to easy to convert an HTML5 structure to an HTML 4-style structure: you just replace the HTML5 elements with <div>s with appropriate IDs to make them easily identifiable for styling purposes, etc.

And you can get HTML5 elements working across all browsers today with the minimum of effort:

First of all, if you put an element into a web page that the browser doesn't recognise, by default the browser will just treat it like a <span>, ie, an anonymous inline element. Most of the HTML5 elements we have looked at in this article are supposed to behave like block elements, therefore the easiest way to make them behave properly in older browsers is by setting them to display:block; in your CSS. You can do this by including the following CSS rule at the top of your CSS, whether it is contained in the head of your HTML file, or an external CSS file:

article, section, aside, hgroup, nav, header, footer, figure, figcaption {

display: block;

}

This solves all your problems for all browsers except one. Older versions of Internet Explorer refuse to allow styling of unknown elements, but this can be fixed by inserting a line of JavaScript into the head of your document for each element, like so:

<script>

document.createElement('article');

document.createElement('section');

document.createElement('aside');

document.createElement('hgroup');

document.createElement('nav');

document.createElement('header');

document.createElement('footer');

document.createElement('figure');

document.createElement('figcaption');

</script>

IE will now magically apply styles to those elements. It is a pain having to use JavaScript to make your CSS work, but hey, at least we have a way forward? Why does this work exactly? There is also a problem with these styles STILL not being carried through to the printer when you try to print HTML5 documents from IE. This print problem can be solved using the HTML5 Shiv JavaScript library, which also handles adding the document.createElement lines for you. You should wrap it up in Conditional comments for IE less than IE9, so modern browsers don't execute JS they don't need.

Don't worry if you don't understand this now - it will be come clearer as you progress through the web standards curriculum.

So, which one to choose?

You may be wondering which style of structural elements to choose, now you've had a tour of the two options. We'd advise that you learn both, and use the HTML5 elements where you can, falling back to the HTML 4 elements for projects where you are worried about the site's audience having JavaScript support (remember that the HTML5 fix discussed above requires JavaScript to work), or where you can't use HTML5 (eg because the brief specifies HTML4, or because you are using some kind of content management system that won't work with HTML5).

This way, you can work with whatever is thrown at you on different projects, plus your HTML5 sites will be nicely future proofed for when browsers do start to support HTML5 structural elements.

Summary

This brings us to the end of our tour through HTML structural elements. Again, don't worry if you don't understand this right now! I have provided a couple of templates containing all the code we looked at in the chapter.

Exercise questions

- Using my templates as a basis, create an outline HTML structure for one of the following sites. Think about what different things such pages might have on them, in terms of header, footer, navigation, main content, sidebars, etc. Look at existing examples if you need to.

- An e-commerce site product listing page (eg listing summaries of the different products available)

- A restaurant menu page

- A full story page for a news site (eg one news story, listed in full)

- What content would be appropriate for putting into the header and footer of a blog post contained in an article?

- What element should you use for the main content column, if JavaScript is turned off?