Mimicking Human Memory

- The Forgetting Curve

- The Spacing Effect

- Stochastic Recall

- Spreading Activation

- Memory Boosting Techniques

- Commentary

- Memory Tests

- Facts and Rules for clustering

- Footnote

This page uses Cognitive AI for a tutorial on modelling memory, learning and forgetting. You might ask why we would want to make computers forgetful, given how faithful they are at remembering. The answer is that in everyday situations you want to recall just what is most important based upon past experience. This is similar to web search engines which seek to provide the results that are most likely to be relevant given the words given in the search query.

There are different kinds of memory, e.g. current information you are working on (working memory), memories of past events (episodic memory), general knowledge about the world (semantic memory), memories of people's faces (visual memory), memories of people's voices (phonological memory), remembering how to dance the rumba (muscle memory). Memory can be considered in terms of stages: encoding, consolidation, storage and retrieval. Encoding and consolidation is about how you initially represent information and subsequently relate it to what you know already.

Different kinds of memories are stored in different parts of the brain, e.g. people's faces, the sound of their names, and facts about their lives. Memory retrieval involves the use of cues to selectively recall relevant memories, including the means to integrate information from different parts of the brain. When retrieving memories of past situations, we try to understand what happened, and to fill in the gaps in our recollection based upon what is likely.

Memory is associated with priming and interference. Priming occurs when the retrieval of one memory makes it easier to retrieve another. Conversely, interference occurs when a memory primes multiple other memories instead of just the ones that are useful or relevant to the current situation. Interference makes it harder to retrieve the correct memory, and can be modelled in terms of stochastic recall between competing memories.

See also further information on chunks and rules.

The Forgetting Curve

In 1885 Hermann Ebbinghaus published the results of experiments he had conducted on his own memory. This showed how our ability to recall memories drops over time in a matter of days or weeks unless the memories are consciously reviewed or reinforced through repetition. Further work showed that repetitions have less effect when they are closer together.

In 1885 Hermann Ebbinghaus published the results of experiments he had conducted on his own memory. This showed how our ability to recall memories drops over time in a matter of days or weeks unless the memories are consciously reviewed or reinforced through repetition. Further work showed that repetitions have less effect when they are closer together.

Work in neuroscience has shown that memories are held in the outer layer of the cortex, encoded in synaptic connections between nerve fibres. When activated, memories are represented as concurrent firing patterns of bundles of neurons in cortical columns, akin to vectors in noisy high-dimensional spaces. Memories are accessed associatively, allowing you to follow relationships between concepts at a symbolic level.

Rather than replicating the human brain with artificial neurons, human-like AI can make use of a functional model of memory in terms of chunk graphs where each chunk is set of properties whose values are literals or references to other chunks. The references form the graph edges, while the chunks form the graph nodes. Chunks combine a symbolic representation with sub-symbolic information that describe the strength of memories in terms of past experience and prior knowledge. Strong memories are easier to recall than weak ones.

The forgetting curve is modelled by associating chunks with:

- a positive number representing the chunk's strength

- a timestamp representing the time the chunk was created or last accessed

- a measure of how many times it has been accessed since it was created

The following graph is dynamically computed and shows how the strength of a single chunk decays like a leaky capacitor unless boosted by being re-added, updated or recalled. In this case, the initial decay rate has been set to drop by half every 3 days, however, that is somewhat arbitrary, and should be set to mimic data from memory tests with human subjects. As the strength decays, and approaches, and then falls below a system-wide threshold, the chunk becomes increasingly harder to recall.

The horizontal green line represents the threshold for recall. This shows that even when memories have been forgotten, further practice can recover them, as illustrated by the sudden jumps in the chunk's strength at 9, 10 and 23 days after it was created.

The effective rate of forgetting is effected by various factor's including:

- Meaningfulness of the information

- The way it is represented

- Physiological factors, e.g. stress and sleep

For human-like AI, we can mimic these factors (at least the first two) in terms of the initial strength of chunks when they are first added, the way that knowledge is modelled with chunk graphs, the way that related memories are boosted through spreading activation, and the effects of interference during stochastic recall. More details are given below.

The Spacing Effect

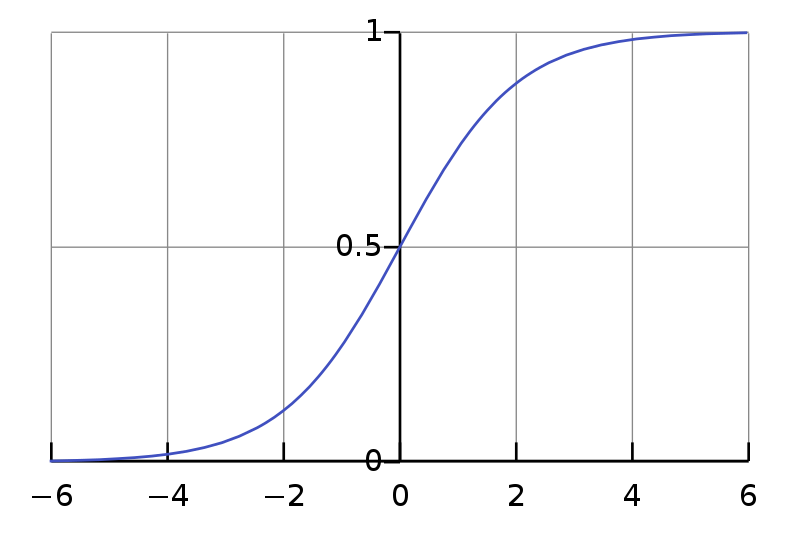

In the earlier graph of the forgetting curve, the rehearsal at 10 days has a reduced effect compared to the rehearsals at 9 and 23 days. The Spacing Effect describes how repetitions have less effect when they are closer together, as this lessens the likelihood that the memory will have continued value further out into the future. This is modelled using the Logistic Function applied to the logarithm of the time interval divided by a characteristic time period. For smaller intervals the effect of repetitions gradually drop off to zero, and for larger intervals the effect of repetitions gradually flatten out.

If memories have been frequently used in the past, then it is likely that they will be useful again in the future, even after a long interval of disuse. This can occur when a given skill isn't needed for a prolonged period due to environmental factors, e.g. different foraging tactics are appropriate during the winter vs during the summer. One way to model this is to make the decay rate inversely proportional to the number of times a memory has been updated or recalled, modulo the spacing effect. This would explain how you can recognise a popular song from your youth that you haven't heard for many years.

Stochastic Recall

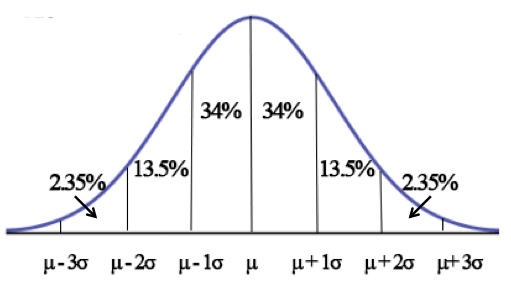

Memory recall is stochastic. This means that when recalling memories of equal strength, the probability of recalling anyone of them is the same. Sometimes, you will recall a weaker memory in preference to a stronger one. However, the likelihood of that rapidly drops off the greater the difference in strengths. This modelled using Gaussian noise where a random number is generated with an average value of zero, and a 95% chance of being within plus or minus twice the standard deviation. In the following figure, the mid-point μ is set to zero.

The chunk strength is multiplied by Euler's constant (e) raised to the power of the value returned by the noise generator. This means that on average the resulting value is close to the chunk strength, but on rare occasions, it will either be a lot smaller or a lot larger. The value is then compared to the minimum strength for successful recall. The standard deviation is reduced for time intervals small compared to the half-life for the forgetting curve. This ensures that recall is accurate for very recent memories.

Spreading Activation

Priming occurs when the retrieval of one memory makes it easier to retrieve another. This is useful in natural language understanding, where the meaning of earlier words influence the likely interpretation of later words. Priming can be modelled in terms of a decaying wave of activation that spreads out across chunk graphs, following references to other chunks, and vice versa. The following example provides an illustration:

cluster {items horse, dog, cat}

word horse {}

word dog {}

word cat {}

Activating the word horse will boost the chunk strength of the cluster it appears in, and in turn, other words in that cluster. This shows that activation needs to spread in both directions: from a chunk to the chunks that reference it, and from chunks to the chunks they reference. Spreading activation can explain why old dormant memories can become easy to recall given the appropriate priming.

The amount of activation is divided evenly across the referenced chunks, thus if one chunk references a thousand others, each of the referenced chunks will receive a thousandth of the activation energy. This is referred to as the fan effect. To ensure that the wave decays in all cases, when a chunk is boosted by a wave, only a fraction of this is redistributed to other chunks. Spreading activation reflects the dynamic nature of recall in the cortex, in terms of stochastic waves of neural activity ringing out across the cortical columns. For more details, see e.g. Lerner, Bentin and Shriki.

Memory Boosting Techniques

People can learn to apply techniques to boost their recall of lists of items or long sequences of digits:

- Relate items to existing knowledge to make them more meaningful. Look for generalisations, e.g. to cluster items that belong to the same class or which are commonly found together. Focusing on learning generalisations first as this will speed learning of examples due to the priming effects of spreading activation.

- Mnemonic sentences: e.g. to help remember the names of the planets in sequence, you might associate this with the sentence: "my very educated mother just served us noodles", where the first letter for each word is a reminder of the corresponding planet's name: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

- Mental imagery, i.e. visualising images of verbal information. Abstract ideas are easier to remember if associated with different forms of non-abstract information, e.g. images, movement, sounds and smells. The memory palace technique involves mentally placing images of things in different rooms of a familiar imaginary palace or castle. You mentally walk through the rooms to recall the images.

- Chunking into groups: e.g. breaking digit sequences into smaller sequences of 3 or 4 digits, as in a phone number. This can be done hierarchically with categories to make the groups more meaningful.

- Rehearsal: consciously rehearsing information will help, but not if you cram everything into a short time, where the spacing effect will come into play.

These techniques show that learning is an active process that combines factual and procedural knowledge.

Commentary

The framework presented on this page was loosely inspired by the work of John R. Anderson, with simplifications intended for greater scalability when engineering human-like AI agents. The current work, for instance, makes no attempt to mimic human recall latency, furthermore, only the last access to each chunk is tracked rather than the full history of accesses.

The framework presented on this page was loosely inspired by the work of John R. Anderson, with simplifications intended for greater scalability when engineering human-like AI agents. The current work, for instance, makes no attempt to mimic human recall latency, furthermore, only the last access to each chunk is tracked rather than the full history of accesses.

ACT-R is a popular cognitive architecture developed by John R. Anderson at CMU. It features a more complex and more costly framework for chunk activation and retrieval than presented in this tutorial, see the introduction to ACT-R 6 by Frank Ritter and Mike Schoelles, as well as the analysis by Jacob Whitehill. Ultimately, any such framework needs to be explainable in terms of neural models of computation, and the demands on memory throughout an animal's life.

In part, this involves a balance between short term and long term needs. Some knowledge is transitory, dealing with the current situation, whilst other knowledge has lasting value. Seasonal knowledge allows animals to adapt their behaviour to match the changing seasons of the year. Such knowledge lies dormant for many months until that season comes again. The forgetting curve involves exponential decay, and a decay rate suitable for short term knowledge would make long term knowledge inaccessible, given extended periods of disuse.

This challenge can be met by adjusting the decay rate based upon an estimate of the long term utility of memories. A low cost mechanism for this is to make the half-life for decay linearly proportional to one plus the aggregate sum of the boost each chunk gets when it is updated or recalled. The boost takes the spacing effect into account, so that closely spaced accesses have less effect. From a neurological perspective, there are a number of different processes acting on different timescales, including synaptic neurotransmitters and neural plasticity.

The cortex implements an associative memory store that can be queried with cues for chunk identifiers and properties. When recalled, chunks correspond to the concurrent firing patterns of nerves in cortical columns. You can think of this in terms of vectors in noisy spaces with many dimensions. The vector for a concept like dog will differ from one person to the next. Human language maps these internal private vectors to vocabularies of words whose meaning is understood by language users. This can be contrasted with the Semantic Web, where web addresses (URIs) are used in place of words. RDF also has blank nodes which are local to each graph.

Working memory can be defined as a limited capacity store for retaining information whilst it is operated upon. Research (e.g. Baddeley & Hitch 1974) suggests that working memory is modular, including such components as the central executive, visuospatial sketchpad, phonological loop and the episodic buffer. That fits with the cognitive architecture proposed for human-like AI in which the cortex is modelled as a number of specialised associative datastores with associated graph algorithms. Perception places short-lived models in the cortex for access by different cortical circuits. Some memories are short term, whilst others have lasting value. Cognitive buffers provide dynamic access to the cortex as part of a model of sequential rule execution for the cortico-basal ganglia circuit.

Spreading activation is related to the encoding and consolidation of memories. The richer connections we can make, the easier it will be to recall memories when we need them. The effort needed during encoding and consolidation reflects the perceived importance of the information. This relates to the attention we give to things. Everyday things get little attention, and it is things that are out of the normal that catch our attention.

One area for further study is how memory works in respect to memories of individual things, memories of sets of things, and memories of ordered sequences. In the memory tests described below, where people or cognitive agents try to remember a set of items seen earlier, a question is whether items are recalled in the original sequence, or as an unordered set of items. This also relates to spreading activation. If you recall one item in a cluster, are you likely to recall all items in the cluster, or are you more likely to remember the following items in the sequence in which you originally learned the cluster?

The chunks library uses two passes through the set of chunks that match the query. The first pass iterates forward to ensure that later chunks can be recalled when sufficiently primed by earlier ones. The second pass iterates backward to ensure that earlier chunks can be recalled when sufficiently primed by later ones.

The approach implemented with the chunks library has several parameters:

- Initial chunk strength: 1.0

- Minimum strength threshold: 0.02

- Standard deviation for noise generation: 2.0

- Time constant for spacing effect: 24 hours

- Initial decay rate: 50% in 3 days

- Strength half-life proportionality: 1.0

These parameters will need to be adjusted to match the desired performance across a wide range of tasks. Humans vary in how good their memory is, and in their ability to learn, so the question is what do we want to achieve with cognitive agents that mimic human capabilities?

n.b. further work will explore approaches for dealing with statistical correlations at an early stage of concept formation for thematic knowledge, i.e. before chunk properties are created to represent relationships between concepts. This involves managing statistics across episodic memory for co-occurrence (which things are commonly found together) and for temporal sequences (which things commonly follow other things) suggestive of potential causal relationships.

Memory Tests

The following provides some tests of memory performance using different levels of encoding.

Imagine you are shown a tray with a set of cards each of which has a word. You are given some time to try to remember them. The tray is then taken away, and some time later, you are asked to write down all of the words that you can remember.

The first part of the test can be modelled by adding a set of chunks where each chunk corresponds to one of the cards on the tray, e.g.

# declare the tray and the words it has

tray tray3 {}

word horse {tray tray3}

word orange {tray tray3}

word table {tray tray3}

word teacher {tray tray3}

word apple {tray tray3}

Alternatively, information about the tray can be modelled as a chunk context, to ensure that the facts about the tray are held distinctly from general declarative knowledge, e.g. as in the following where context c1 represents episodic knowledge that is only true in a given context:

# this episode has a tray and a set of words

tray tray3 {@context c1}

word horse {@context c1}

word orange {@context c1}

word table {@context c1}

word teacher {@context c1}

word apple {@context c1}

For the second part of the test, we see how many chunks can be recalled after a given time interval. In the simplest case, the words are unrelated and spreading activation has little effect as it is divided across all of the cards on the tray.

Here is a table containing a random selection of words:

| Nine | Swap | Cell | Ring | Lust |

| Plugs | Lamp | Apple | Table | Sway |

| Army | Bank | Fire | Hold | Worm |

| Clock | Horse | Color | Baby | Sword |

| Desk | Grab | Find | Bird | Rock |

The following allows you to run the memory test with unrelated words from the above table. You can choose the time delay for applying the test after being shown the tray. The results are stochastic and likely to vary from one run to the next.

Run test1 with given time delay:

Test results:

Words recalled:

If the words are related, this allows you to group them into clusters of related words. This can be modelled in terms of chunks that represent the individual clusters. With fewer cards in each cluster, and a few clusters for the tray, spreading activation has a much greater impact, improving the probability of recall.

Here is a table where the entries can be easily clustered by category:

| Horse | Cat | Dog | Fish | Bird |

| Orange | Yellow | Blue | Green | Black |

| Table | Chair | Desk | Bookcase | Bed |

| Teacher | School | Student | Homework | Class |

| Apple | Banana | Kiwi | Grape | Mango |

How can a human-like AI agent create the clusters? In principle, an agent could try several different approaches to see which works best, and discarding the clusters that aren't useful. This involves heuristics for selecting an approach, the means to apply each approach, along with the means to evaluate their results, and to discard unwanted clusters. All of this could be implemented using a mix of facts, rules and graph algorithms.

The facts include background knowledge about the meaning of words, e.g. words for different kinds of animals, and words for things commonly associated with education:

# taxonomic relationships cat kindof animal fish kindof animal # thematic relationships teacher partof education school partof education student partof education

You might know the names of many different kinds of animals. This dilutes the effect of spreading activation, and explains why it is important to explicitly represent clusters of cards, e.g.

cluster cl {items horse, dog, cat, fish, bird}

cluster c2 {items orange, yellow, blue, green, black}

...

Clusters could be proposed based upon:

- chunk types

- relationships between chunk types

- chunk property names

- chunk property values

- richer taxonomic knowledge involving classes and properties

- thematic knowledge about co-occurence of related information

The following test uses clustered items using the following representation:

cluster cl {items horse, dog, cat, fish, bird}

cluster c2 {items orange, yellow, blue, green, black}

...

word horse {}

word orange {}

...

Run test2 with given time delay:

Test results:

Words recalled:

The following test makes the relationship between the clusters and the tray explicit:

tray tray1 {clusters c1, c2, c3, c4}

cluster cl {tray tray1; items horse, dog, cat, fish, bird}

cluster c2 {tray tray1; items orange, yellow, blue, green, black}

...

word horse {tray tray1}

word orange {tray tray1}

...

Run test3 with given time delay:

Test results:

Words recalled:

The following test recalls the clusters directly, i.e. using a query for chunks of type cluster rather than of type word:

Run test4 with given time delay:

Test results:

Clusters recalled:

Words recalled:

How do people decide how to form the different clusters? While this may be obvious for some lists, it will be less so for others.

- Hard Clustering: In the above example, something either is a fruit or it isn't, so it's easy to make the distinction. In hard clustering, you separate the items by distinct qualities. Think about what makes the items in the list distinct. You may have some leftovers that don't seem to have qualities in common.

- Hierarchical Clustering: Start with all of the objects in the group and begin to group them two by two for the ones that are the most similar. Then look at the pairs and group the closest pairs together so that you now have groups of four. For simple memorization, that's probably as far as you want to go.

This is an opportunity for a synergistic blend of cognitive rules and graph algorithms. Using rules alone would be complicated and slow, e.g. creating an index by properties and counting the number of entries. Graph algorithms will be a lot more efficient, but have limited flexibility on their own. This could be compensated for by using a suite of algorithms for different purposes under the control of rules, along with the means to control algorithms via parameters passed from the rules.

Further work is expected to explore the effects of different ways of organising knowledge on recall. Concepts can have two very different kinds of relations: similarity relations based on shared features (e.g., dog – wolf), which are called “taxonomic” relations, and contiguity relations based on co-occurrence in events or scenarios (e.g., dog – collar), which are called “thematic” relations. See the survey paper by Mirman, Landrigan & Britt, 2017.

In principle, thematic relations are learned first, based upon co-occurrence within individual episodes, whilst taxonomic relations are learned later, based upon generalising across different episodes. This points to future demos on learning from experience, the role of analogies, metacognition and hierarchical reinforcement learning. This will in turn drive work indexing facts and rules for scalable cognitive databases, mimicking the function of the anterior cingulate gyrus.

Facts and Rules for clustering

The button below triggers the start goal to initiate clustering based upon the kindof and partof relationships as given in the facts graph, and respectively representing taxonomic and thematic knowledge.

- the clusters are shown in the log below.

Log:

Facts graph:

Rules graph:

n.b. many thanks to verywellmind.com for the tables of words and the above account on clustering.

Dave Raggett <dsr@w3.org>

This work is supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 957406 for project TERMINET, which focuses on next generation IoT.

This work is supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 957406 for project TERMINET, which focuses on next generation IoT.