Headers footers columns and templates

Introduction

To this point, the articles in the Web Standards Curriculum have focused on single topics, ranging from soft concepts like typography and colour, to hard technical instruction on subsets of CSS 2.1. This article takes on broader focus; its purpose is to show the reader how to take the material covered so far, and use it to build a complete site template.

The principal assumption of this material is that you are already familiar with the CSS float, display, and position properties.

Self directed learners who want to leap straight into the meat of the CSS are reluctantly invited to skip to section IV of this article, “Single column layout implementation” — but should note that in doing so, they will neglect discussion of how successful project planning leads to the layout and implementation of a Web site.

Those same impatient souls who disregard the caveats given in the preceding paragraph will also want to download the single, double, and triple column templates that are provided with this article, and will be linked to again at its conclusion.

Note: you can download all of the sample code in one convenient package, to experiment with it on your local machine.

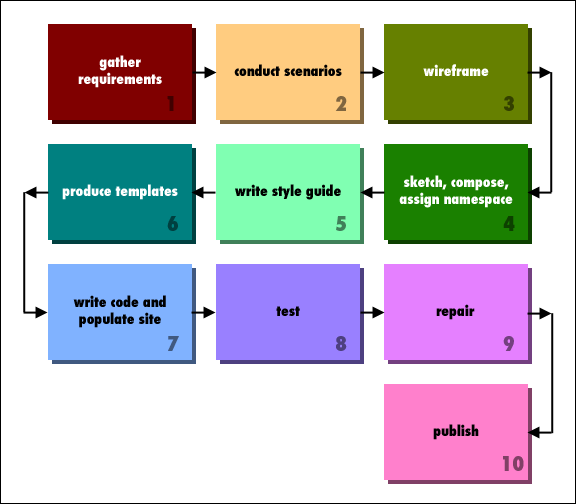

A properly built site typically results from a deliberate, mostly serial process, even if the site is built by one or two people rather than an entire team of specialists. A fairly elaborate rendition of such a process is outlined in Figure 1, and of the ten steps described there, this article focuses on four in particular:

- Gathering of requirements based upon business objectives and the consequent visitor objectives

- Content classification

- Collaborative sketching and composite creation

- Establish the structure of the documents to be used on the site

Once those four steps are completed, the stylist possesses most of the information he needs to build the site layouts, which will typically have one, two, or three columns. Regardless of the general form of the layout, there will be differences from one section of a site to the next, which will in turn influence how certain elements and style selectors are made part of the overall site design.

Even after the design and structural choices have been made, there remains the question of how production will be handled if the site is to be built atop a Content Management System (CMS) such as Wordpress or Drupal.

This article underscores the importance of the four steps mentioned above; provides a simple framework for content classification; and describes how to lay out a site with complete headers, footers, and columns.

The stylist’s critical process steps

The following two sections are provided as embellishment to other articles in this curriculum, with an an emphasis on planning and process rather than implementation. Their central message is “look before you leap” — in other words, form a clear understanding of what you are going to implement before you start on markup, stylesheets and code!

Figure 1: Ten common steps of the sitebuilding process. Those that are especially relevant to this article are presented in inverse.

Gathering objectives

Good CSS relies on a chain of dependencies:

- CSS relies on structure to work;

- Structure is informed by content;

- Content needs scope;

- Content scope is ultimately defined by likely visitor objectives; and

- In their turn, visitor objectives travel hand in hand with business objectives.

The point to this chain of requirements is that the needs of your visitors will point directly to the structure you need to create for your site, and thereby drive the selectors and techniques applied in your styles.

When the requirements gathering process is handled poorly, stylists can expect to face challenges that might include:

- Missing assets

- Lack of guidance as to the relationship between layout behavior and window geometry

- No definition of platform support tiers

- Frequent change requests, as requirements are cobbled together during the implementation process

- Lack of current tools

Content classification

Once you’ve determined the scope of your site content, you need to define its importance to the site as a whole, and decide what navigation aids you will provide for visitors to find it.

There is also the question of what to do with matter such as advertising, link lists, galleries, and comments.

Once classified, content can then be associated with the site’s navigation and given weight. Content weighting will be discussed here in a primary/secondary/tertiary context, since a content block's importance should be reflected by its position in a document's source order.

Collaborative sketching and composite creation

If you are working on a project where graphic design and style implementation are roles assigned to different people — which is often the case in commercial projects — the graphic designer should rely on sitemap diagrams and wireframes (if available) to start creating the look and feel of the site. It can be valuable to start out with simple sketches, as a way of defining things like the site’s general motif, its consistent features, and the details that might complicate the markup or the class and id assignment.

With sketches agreed upon, the graphic designer can then move onto the finished composites, which should be similar to screen captures that might be generated in the development browser after the site is put into production.

Henceforth in this article graphic design will be getting short shrift, as it has already been discussed in the curriculum articles about wireframes and composites/mockups.

Establishment of inter- and intra-document structure

With the composites in hand, the stylist can start writing the markup and CSS. The first step of doing that work is to decide upon the content order, element nesting, classes, and ids that will be used on the production site — work that can only be done at its best if the stylist has a complete understanding of the content to be served on the site, and the manner in which it is to be laid out.

Requirements, classification, and element nesting in more detail

If one follows modern best practices and adopts the User Centered Design (UCD) paradigm for driving design and development decisions, then visitor objectives inform every step of the design process.

However, the objectives of the site’s sponsor (or publisher) actually take precedence from a design team’s perspective, because without knowledge of those goals, the design team has no way to anticipate visitor goals.

Defining business objectives

The “business” objectives of the site will fall under one or more of the following general definitions:

- Directly generate revenue (e-commerce)

- Provide publishing, messaging, and/or storage services via a Web interface (eg, Blogger, Flickr, Scribd, YouSendIt, Basecamp)

- Market a product or service

- Provide information

- Entertain the visitor

Once the general objectives have been established, there will be further refinement based upon any of a number of factors, like demographics, conversion goals, and design constraints imposed by the project’s budget or the nature of the content itself (as might be the case with something like Flash video).

Experience is by far the best teacher when it comes to guiding this part of the requirements gathering process.

Defining and meeting visitor objectives

With business objectives established — “this is what we want our visitors to see and do” — the next step is to attract and lead visitors to those destinations and types of functionality that best suit them.

The principal assumption of this part of the design process is “visitors hate obstacles.” The best ways to meet that assumption are:

- Define and design navigation that best suits the most likely visitor wayfinding strategies. These strategies can include fulltext search, traditional taxonomically-driven lists of links, or “tagging” (whether moderated or user-defined). Note that a site can cater to more than one wayfinding strategy.

- Always provide cues to indicate a visitor’s position within the site as a whole. Common means of doing so include “breadcrumb trails,” links to related content, and visual cues such as context-dependent navigation link design.

- Enforce visual and writing style as rigidly as you can, without hewing to a foolish consistency. This practice is closely tied to the need to give the visitor consistent cues about location; the difference is that where colour and navigation layout offer a user their bearings within an entire site, consistent presentation across pages is essential to providing bearings within a single page.

- Always indicate in plain language the consequences of following a link or making a form submission. Sometimes this is as simple as labelling a submit button with the word “Search” but sometimes you might need to provide a note to give site visitors more instruction.

- Provide a clear distinction between design elements that will respond to user interaction, and everything else. Styles that make links barely distinguishable from normal copy, inconsistent button design, and atypical

cursorstyles are all common, and all confusing. High contrast colours, thoughtful use ofpadding(to enlarge the footprints of interactive design elements), and informativetitles are typically more effective. - Minimize the amount of user interaction (especially the number of link or button clicks) required to achieve a common goal, such as a purchase, or serving of popular resources. In practice, this usually requires roleplaying and analysis of visitor choices. Unless and until those tasks can be completed, the shortcut to following this guidance is to obey the spirit of the KISS (Keep it simple, stupid) Principle.

When it comes to markup and stylesheets, there are a few simple techniques to follow that make these rules easy to follow:

- When drawing up your stylesheet, assign as many properties as possible in rules with simple element selectors.

ids by definition are unique, and to be usefulclasses are best reserved for uncommon cases (or presentation requirements that cannot be properly supported in legacy browsers without them). However, by moderating their use attentive stylists become alert to instances where the graphic designer is insisting upon potentially expensive levels of detail in their designs. - Assign an id to the body of every page. If individual documents (and not just sections of a site) are assigned stylesheet tokens, unique presentation cases become much easier to handle. Another benefit of putting an

idon thebodyof each page is that when used in tandem with similarly weighted navigation elements, the stylist can then provide visual cues in the primary navigation for things like the currently viewed section or site, without needing to resort to verbose server-side logic. - Avoid designs that place high demands on a visitor’s fine motor control. A harsher way to describe this guidance is “avoid flying menus like those created by use of Suckerfish techniques (see here for a different set of Suckerfish techniques), also known as drop down menus. There are clear use cases for such designs, and they all involve large sites that rely on one- and two-column layouts, but they are often avoidable. On the other hand, inexperienced and motor-control-impaired users often find drop down menus problematic:

- In order to be effective such elements often require the links they contain to be smaller than the default size for bodycopy type — a counterintuitive visual cue that makes the menu items seem less like links than other surrounding page elements.

- The extent of fine motor control required to use these elements easily frustrates inexperienced, casual, and impaired visitors.

- The range of possible destinations available within a given section of the site is hidden until the visitor interacts with such elements; this limits their ability to maintain a sense of location within the site until they’ve gained experience with using it.

Content classification

Once you’ve worked out the scope of the content to be served on the site, you can give it an architecture. A site’s architecture can be worked out in various ways (see an earlier article for some examples).

Generally, you’ll be able to assign priority to your content that will inform likely layouts:

- Primary content is the matter around which individual destination documents are built, such as articles, photo albums, or datasets.

- Secondary content includes human-readable metadata attached to the primary content, and sidebar content (e.g. expository copy; review excerpts; links to related articles on the site; lists of charts, maps, or tables).

- Tertiary content encompasses outgoing links to related material (such as a blogroll), persistent snapshots of content from other sources such as social networking sites or comment feeds, and advertising.

In addition to content, your layout will almost certainly include two other sections:

- The header will include the site title (which often links to the topmost page on the site), the primary navigation, links to user account metadata (in an application), and finally the main content search form (if deployed).

- The footer contains the copyright statement, at bare minimum. Links to documents composed of metadata (such as RSS feeds, sitemaps, and site meta-content part from contact info) also find their way into a site’s secondary navigation, which is typically made part of the footer.

A site’s primary navigation and title are nearly always part of (or flush to) its header in a visual context; it is left up to each implementer to decide if they should be made part of the site’s header at the markup level.

Source order: accessibility and other considerations

An early step of designing site templates is to decide upon the source order of its content, which should be consistent across the site as a whole.

Document source order that reads properly without the benefit of stylesheets is essential for reasons of accessibility and cross-media support. In the case of the former, vision-impaired users can use what are called screen readers: software suites that read content aloud to the visitor, content which makes little or no sense if it’s ordered willy-nilly for the sake of presentation.

And just as source arranged in the optimal order for screen display probably wants for clarity when read aloud, it might prove impossible to style in other media such as print or mobile displays. In that event the outcome is usually duplicate content, which offers a number of drawbacks:

- At minimum, additional View layer logic must be implemented to account for the fact that output from a single database record can be served in more than one fashion.

- In a worse case, content is duplicated not only in the visitor-facing environment, but also in the database or host filesystem. The result will be doubling of some upkeep requirements.

Thus, it’s most common to arrange the outermost sections in the following order:

- Header

- Title [preferably links back to top/home/landing page]

- Primary navigation

- Primary content

- Document title

- Body copy

- Secondary content

- Tertiary content

- Footer

- Secondary navigation

- Additional bits (eg, copyright notice)

The manner in which these sections are nested will depend upon any number of variable requirements, the most common of which is the number of static columns in the site layout.

Container element, class, and id assignment

Putting aside questions of taxonomy, we can assume that any given site will cover a range of related subjects within an understood scope — be it the operations and products of a company, specific types of events, or specific kinds of entertainment, to name a few examples that can usually be counted upon to arouse appeal in non-technical audiences.

Therefore, the stylist will likely find themselves associating stylesheet tokens with both structural elements of the site contents — eg navigation bits, header, bodycopy — and ranges of content, whether narrow or broad.

Practices vary, but the author usually assigns the following layout tokens to his templates, tokens that will see use in this article:

#maincontent canvash1(unique) site titleul#navsite navigation#breadcrumbbreadcrumb trail (if used)#bodyCopymain article#bodyCopy>h2(unique) primary document title#sidebarsecondary content#footerfooterul#secondaryNavsecondary navigation

In addition to — and more importantly — than these, an id is added to the body of each page (as mentioned above) that gives some indication of the scope of the primary content associated with the whole document. Some projects also generate a requirement for the assignment of classes to body elements, as well.

Single column layout implementation

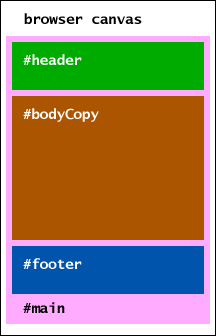

Figure 1: The elements of a single column layout; the markup will likely be nested as shown here.

Figure 1 shows that #main is immediately within body, and in turn contains all of #header, #bodyCopy, and #footer.

Centering the layout

Centering the content canvas is a matter of inserting (in this case) #main { width: 960px; margin: auto; } into your stylesheet. (The width value chosen is arbitary.)

Is a document-wide container strictly necessary?

In a site that relies entirely upon single column layouts, it is not an absolute requirement to include #main; one could as easily apply the same layout property/value pairs used above to #header, #bodyCopy, and #footer in combination. However, there’s nothing semantically wrong with including #main, and its inclusion offers the stylist more flexibility with respect to things like rules, gutters, background images, and building the prominence of certain elements into the structure of the template.

Double column layout implementation

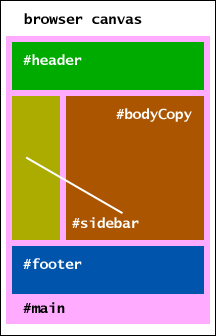

Figure 2: The elements of a double column layout; the markup will likely be nested as shown here, with the understanding that #sidebar will actually follow #bodyCopy in the source order.

The difference between single and double column layouts lies in the addition of a second container element for the secondary content (#sidebar, which actually follows #bodyCopy in the source order), and some changes to the stylesheet likely to be used for a single column layout.

Composition issues vis-a-vis single and double column layouts

The changes to the markup needed to convert a single column template into a double column template are straightforward, but in many circumstances the new style rules needed are not.

Placing #sidebar to the left in spite of its source order

There are two procedures for doing this; one will work regardless of the length of either column, while the other requires #bodyCopy to be longer than #sidebar.

The first and most common approach is to use float:

- Assign a

widthvalue to#bodyCopy. - Add to that rule a

floatvalue ofright. - Assign an appropriate

widthto#sidebar. - Assign

marginandpaddingvalues as needed to#bodyCopyand/or#footerby way of ensuring that the desired gutter exists between the two elements. - Assign

clear: both;to#footer.

Both columns have width values specified so that both will have consistent margins.

In the case where #sidebar instead lies at the right margin of the layout, the steps already described should still be followed, except that the float value of #bodyCopy should instead be set to left. The width value assigned to #sidebar should be replaced with an appropriate margin-left value.

It is also possible to assign a large margin-left or margin-right value (as needed) to the un-floated element, in lieu of width.

A second approach less likely to trigger bugs in Internet Explorer 6 is to assign a large margin-left or margin-right value to #bodyCopy as appropriate, and absolutely position #sidebar. However, this approach is less flexible, since cases in which #sidebar is longer than #bodyCopy will cause the former element to bleed into #footer.

Faux columns: using a background image to even up column lengths when the length of their content differs

Closer examination of column implementations using the float property reveals that when differing background colours or vertical rules between columns are desired, they cannot be counted upon to run down the length of the main content area when applied with background-color or border properties.

The easiest solution to this problem is to create and specify a background image (usually one pixel in height) on one of the columns’ ancestor elements which — because of its assignment to that ancestor element — will always repeat from the top to the bottom of the tallest related column. Thus:

#main {

background-image: url(images/bg_2column.gif);

background-repeat: repeat-y;

}

If bg_2column.gif is composed of two bands of highly contrasted colours that correspond more or less precisely to the widths assigned to your content columns, the result will be two columns that appear to have the same height… but actually don’t, as would be discovered if one then goes on to insert the following rules:

#bodyCopy {

background-color: #ccc;

}

#sidebar {

background-color: #999;

}

Taking this step does not necessarily remove the need to apply color or background-color properties to a given column; if the default text colour is unreadable against one or both columns, their background and foreground colours should be explicitly specified in the stylesheet as a fail-safe against the possibility of the browser failing to load background images.

Once a second column has been added to the layout, it will probably seem natural to place the primary site navigation at the top of that column… but how does one do so when that navigation rests in a different part of the template structure?

The answer to that question lies in positioning:

- If

overflow: hidden;is assigned to#header, Make#nava direct descendant of#main. In almost all cases, it will be possible to do this without mangling the desired source order. - Assign

position: relative;to the immediate ancestor of#nav, andposition: absolute;to#navitself. - Since the absolute position of

#navwill place it at the top left corner of its ancestor by default, adjust theleftandtopvalues of#navas desired under the circumstances. - Adjust the

margin-toporpadding-topvalue of#sidebar(as appropriate) to reflect the expected height of#nav. In cases where the height of#navchanges from one page or section to the next, it will be necessary to write multiple rules, perhaps with multiple selectors in each — thus the advice supplied above to assign a content-scope-referentid(and perhaps aclassalso) to thebodyof each document on the site.

Triple column layout implementation

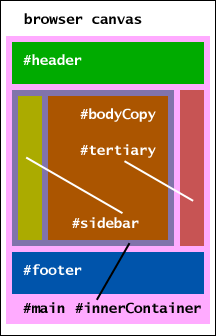

Figure 3: The elements of a triple column layout; note the two new container elements and the differing id assignment.

The principal markup differences imposed by the addition of a third column are:

- A container encloses two adjacent columns, usually the first and second; and

- The third column is placed within its own container.

Once the markup has been laid down, getting the desired layout is a question of ordering float values properly. Don’t forget that the non-floated containers require margin adjustment to line up properly.

Note that with respect to Figure 3, the dual column and tertiary container elements are best assigned ids that offer some clue of context, rather than the generic ids suggested in the diagram itself.

| Desired presentation | Container contents | Container | Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–1–3 | 1+2 | left

|

right

|

none

|

none

|

| 2–3–1 | 2+3 | left

|

none

|

left

|

none

|

| 3–1–2 | 1+2 | right

|

left

|

none

|

none

|

| 3–2–1 | 1+2 | right

|

left

|

none

|

none

|

| 1–2–3 | 1+2 | left

|

left

|

none

|

none

|

| 1–3–2 | 2+3 | right

|

none

|

right

|

none

|

Table 1: float values of the four container elements of a three column layout according to order of appearance from left to right.

The biggest pitfall of three-column designs, and its easy solution

The most flexible three column layout introduces a container element that’s semantically meaningless; the alternative is to enforce conventions of content length or source order that will create an onerous burden, placed either upon maintainers (in the case of content length requirements), or upon visitors (in the case of source order limitations).

The introduction of that “meaningless” container can also pose problems when it comes time to redesign a site. Consider the following scenario:

A site when first designed is laid out with its columns in a 2–3–1 order of presentation, but is later redesigned with its columns in a more traditional 2–1–3 order. The dual-column container element will need to be moved so that it encompasses different column containers. What then?

In such a case, the outcome is easy to achieve; if the site is truly template-driven, then there are (probably) few files to change. If — on the other hand — all of the documents on the site simply uses the same markup framework, search-and-replace must be used. However, this won't be difficult.

The overall markup arrangement of containers will take one of the two following forms:

<div id="#container"><div id="primary">…</div><div id="secondary">…</div></div><div id="tertiary">…</div><div id="primary">…</div><div id="#container"><div id="secondary">…</div><div id="tertiary">…</div></div>

In those two examples, the bits relevant to search-and-replace have been displayed in boldface. Since those ids will be unique in your document, and since the location of the double closing tags can be predicted (either adjacent to a third closing tag, or to #tertiary), writing a search-and-replace operation to alter them is a relatively light challenge.

Up to this point there’s been discussion of the matter that ought to go into headers and footers — logo/logotype, sitewide search, links to user account information, site metadata — but header/footer effectiveness and attractiveness has been little discussed outside the Curriculum articles about wireframes and composites/mockups.

Since it’s poor to immerse the reader in pontification, a better idea might be to take three sites that are notable — either for their popularity, or for the prominence of their publishers — and take a look at their various particulars of design.

Personal site: Cindy Li

Figure 4: There are two matters of note especially worthy of discussion here: identity and contrast.

Identity

“Identity” is a term that takes on special meaning in the realms of advertising and marketing, where it refers to trademarks and other design elements that are particular to the presentation of a commercial enterprise and its products. Cindy Li's site enforces this at a personal level by featuring a caricature of her facial profile into the site header, and a distinctive typeface to set her site title and primary navigation.

The manner in which identity is enforced on enterprise sites will be discussed in more detail below,

Contrast

On cindyli.com, it’s obvious to the visitor at first glance what things are: the identity, content canvas, and primary content are all placed within footprints made discrete through their background colours. In addition, the site title and navigation are given high contrast against their background.

Now for the site footer:

Figure 5: Cindy Li’s footer is somewhat sparse: there are a copyright statement, a link to the marketing site for the publishing platform she uses (which is probably required under the terms of its use license), and a link to a syndication feed of the articles she publishes.

Unlike the other sites presented in this article, Cindy's site doesn't offer fulltext search, probably for technical reasons. However, since the site is a blog, its design allows the assumption that most readers confine their interest to new content.

Social networking: Facebook

Figure 6: Facebook, like many social networking destinations, enforces its identity through its use of layout and colour, since the application itself is the destination.

Like many commercial sites, Facebook offers both fulltext search and a categorized approach to site navigation.

Figure 7: Like its header, Facebook’s footer is also small, even once the persistent application widget at the very bottom is taken into account. The one thing of interest seen here is next to the copyright statement: a widget for changing the user’s default language.

Another common practice exemplified by the Facebook footer is that while links of use to user wayfinding go into the header, the footer contains all of the links about the site operator, and the site itself.

Enterprise marketing and customer service: BNSF Railway

Figure 8: Like most “enterprise” sites, the highest contrast of the header features is enjoyed by the site publisher’s logo… and the only hue present is the same as that used in the logo.

Identity revisited

With respect to distinct logos, logotypes, and other design tropes that enforce commercial identity, consider the following, which are all ubiquitous marks of enterprises that do business with Opera Software:

- Nokia

- Samsung Group and Samsung Electronics

- IBM

Beyond these four, other similar examples of graphic design are well known: the Nike Swoosh (the name of which is actually registered with the authorities), the AT&T “Death Star” logo, the FedEx logotype (and the arrow in the whitespace enclosed by its last two letters), and “UPS Brown” are all examples of corporate identity that are almost universally known to the general public (at least in the USA).

Any site operator who takes the trouble to develop a distinctive visual identity is well served to integrate that identity into the design of their site, an action which has a strong impact on the nature of the stylist's work.

As for other elements in the BNSF site header apart from the logo, the most notable is the use of two wayfinding modes (as is the case at Facebook).

Figure 9: The BNSF site has the most “traditional” footer layout of these three sites, in that little effort is made to place the secondary navigation within a distinct visual plane with horizontal rules or a differing background colour.

In taking a broader view of header and footer design, the following commonalities become clear:

- Enterprise and application destinations tend to lay out their primary navigation in a row along the top margin of the browser canvas. This fact distinguishes them from news and e-commerce sites, which often use a more columnar approach to navigation layout.

- Just as horizontally oriented primary navigation is common, so is the use of discrete secondary navigation in the footer. Furthermore, the destination-versus-site-metainfo division described early in this article is pretty commonly enforced.

- Where fulltext search is present, its input fields tend to be placed near the right margin of the header. This is due in no small part to the fact that well-implemented fulltext search is just as valid a way to navigate through a site as are traditional, taxonomically-driven navigation links — and likely to be abused by a subset of your site’s visitor population, likely to be among the least technically-inclined of your users.

Before there’s any dive into details, the reader should first consult the [1], an application hosted at Accessify.com that creates navigation elements with simple styling, ready for insertion into any page layout.

Beyond the matter of tools that do the work for you, there are two basic approaches to navigation layout:

- The navigation is made integral to the site header (visually if not literally) and oriented horizontally. In this case, the

displayvalue of the individual links will likely be changed toblock, and their containing list items will be assigned afloatvalue ofleft. - The navigation is oriented vertically and placed to the left of the primary content, either in its own column or just above non-primary content. In this case, you’re most likely to see some kind of non-

staticpositioning put to use.

Sites with varying numbers of columns: cheating with classes and display

Some sites might well have pages with one or two columns, others two or three; flexibility is one of the strengths of CSS, and one of the hobbyhorses that graphic designers unwittingly ride in their lustful quest for ironfisted control over the user experience.

Normally, such cases are handled in part with includes: site scripting that allows persistent bits to be added to a page programmatically, rather than being repeatedly copied.

However, even with includes stylists still encounter differences in layout; how best to handle these?

The most straightforward approach is to attach a class to the body of any page that might need it. These might take on an ordinal nature that corresponds to some series of layouts suggested in identity guidelines, or relate back to content and result in multiple-selector rules like the following:

.about #bodyCopy,

.contact #bodyCopy,

.privacy #bodyCopy {

float: none; width: auto;

}

.about #sidebar,

.contact #sidebar,

.privacy #sidebar {

display: none;

}

The one drawback to taking this approach without the benefit of include statements (a poor man’s way of making content disappear or reappear, if you will) is that search engine operator policies might well reduce the weight of those pages in results — or in the case of spectacularly clumsy implementations, delist sites that use them, altogether. For this reason (among too many others to count), any hosting arrangement you obtain should support some sort of include functionality.

Summary

While it’s tempting — particularly if you’re still a beginner — to just sit right down and get to writing markup and code, such a process does not lend itself to especially attractive, useful, or maintainable sites.

However, by taking into careful consideration the content that will go onto a site and the manner in which it ought to be arranged, you can pour any site into the framework that derives from its requirements.

Basic templates:

Exercise questions

- Given a list of possible links provided by your instructor, divide those into primary (header) and secondary (footer) links. Justify your assignments by relying on examples provided in this article.

- Take a composite created by a classmate and identify:

- the number of columns to be employed in the design;

- the widths of those columns; and

- the

float/width/margin - the

float/width/marginscheme, if any, that should be used to implement the presentation of those columns.

- Given a logotype, a list of requirements, and an architecture, design a site header.

- If you cannot prove the use of the Golden Section in the composition of the header designed in the previous exercise, alter its composition appropriately and subjectively evaluate the attractiveness of the result.

- Relying solely on search engine results, obtain the reason why lists are preferable to collections of

divs (or other elements) for structuring navigation elements. Reference the characteristics of screen reader software in your answer. - From memory, revise one of the provided template files so that it supports a different number of columns. Also alter significantly the composition of the primary navigation, in comparison to what was found in the original template file.

Bibliography

- BNSF Railroad. 2006. (last accessed 13 January 2009).

- Facebook. 2008. (last accessed 13 January 2009).

- Henick, Ben. 2006. Avoid edge cases by designing up front. A List Apart. (last accessed 13 January 2009).

- Li, Cindy. 2008. The Adventures of Cindy Li. (last accessed 13 January 2009).

- Morville, Peter, and Rosenfeld, Louis. 2006. Information architecture for the world wide web, 3rd edition. Cambridge, Mass.: O’Reilly Media.

Note: This material was originally published as part of the Opera Web Standards Curriculum, available as 38: Headers, footers, columns, and templates, written by Tommy Olsson. Like the original, it is published under the Creative Commons Attribution, Non Commercial - Share Alike 2.5 license.