Design Strategies

The Web application platform requires the availability of a vast array of functionality that can greatly vary in nature. As a result, not all APIs can look the same, and no single approach can be applied automatically across the board in order to take privacy into account during API design. This section therefore lists strategies that API designers are expected to adapt to the specific requirements of their work.

Action-Based Availability

We seldom pause to think about it, but the manner in which mouse events are provided to Web applications is a good example of privacy by design. When a page is loaded, the application has no way of knowing whether a mouse is attached, what type of mouse it is (let alone which make and model), what kind of capabilities it exposes, how many are attached, and so on. Only when the user decides to use the mouse — presumably because it is required for interaction — does some of this information become available. And even then, only the strict minimal is exposed: you could not know whether it is a trackpad for instance, and the fact that it may have a right button is only exposed if it is used.

This is an efficient way to prevent fingerprinting: only the minimal amount of information is provided, and even that only when it is required. Contrast it with a design approach that is more typical of the first proposals one sees to expose new interaction modalities:

var mice = navigator.getAllMice();

for (var i = 0, n = mice.length; i < n; i++) {

var mouse = mice[i];

// discover all sorts of unnecessary information about each mouse

// presumably do something to register event handlers on them

}

The “Action-Based Availability” design strategy is applicable beyond mouse events. For instance, the Gamepad API [[GAMEPAD]] makes use of it. It is impossible for a Web game to know if the user agent has access to gamepads, how many there are, what their capabilities are, etc. It is simply assumed that if the user wishes to interact with the game through the gamepad then she will know when to action it — and actioning it will provide the application with all the information that it needs to operate (but no more than that).

User Mediation

By default, the user agent should provide Web applications with an environment that is privacy-safe for the user in that it does not expose any of the user's information without her consent. But in order to be most useful, and properly constitute a user agent, it should be allowed to occasionally punch limited holes through this protection and access relevant data. This should never happen without the user's express consent and such access therefore needs to be mediated by the user.

At first sight this appears to conflict with the requirement that users be asked to make direct privacy decisions as little as possible, but there is a subtle distinction at play. Direct privacy decisions will prompt the user to provide access to information at the application's behest, usually through some form of permissions dialog. User-mediated access will afford a control for the user to provide the requisite information, and do so in a manner that contextualises the request and places it in the flow of the user's intended action.

A good and well-established example of user-mediated access to private data is the file upload form control. If we imagine a Web application that wishes to obtain a picture of the user to use on her profile, the direct privacy decision approach would, as soon as the page is loaded, prompt the user with a permissions dialog asking if the user wishes to share her picture, without any context as to why or for what purpose. Conversely, using a file upload form control the user will naturally go through the form, reach the picture field, activate the file picker dialog, and offer a picture of her choosing. The operative difference is that in the latter case the user need not specifically think about whether providing this picture is a good idea or not. All the context in which the picture is asked for is clearly available, and the decision to share is an inherent part of the action of sharing it. Naturally, the application could still be malicious but at least the user is in the driving seat and in a far better position to make the right call.

A counter-example to this strategy can be seen at work in the Geolocation API [[GEOLOCATION-API]]. If a user visits a mapping application in order to obtain the route between two addresses that she enters, she should not be prompted to provide her location since it is useless to the operation at hand. Nevertheless, with the Geolocation API as currently designed she will typically be asked right at load to provide it. A better design would be to require a user-mediated action to expose the user's location.

This approach is applicable well beyond file access and geolocation. Web Intents [[WEBINTENTS]] are currently being designed as a generic mechanism for user-mediated access to user-specific data and services and they are expected to apply to a broad range of features such as address book, calendar, messaging, sensors, and more.

Minimisation

Minimisation is a strategy that involves exposing as little information as is required for a given operation to complete. More specifically, it requires not providing access to more information than was apparent in the user-mediated access or allowing the user some control over which information exactly is provided.

For instance, if the user has provided access to a given file, the object representing that should not make it possible to obtain information about that file's parent directory and its contents as that is clearly not what is expected.

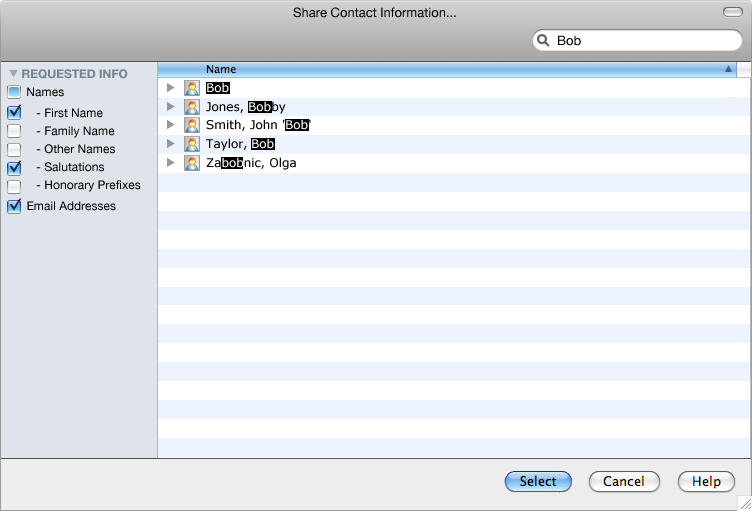

During user-mediated access, the user should also be in control of what is shared. For example, if the user is sharing a list of contacts from her address book it should be clear which fields of these contacts are being requested (e.g. name and email), and she should be able to choose whether those fields are actually going to be returned or not. An example dialog for this may look as follows:

In this case the application has clearly requested that the First Name, Salutations, and Email Addresses fields be returned. If it seems unnecessary to the user, she could unselect for instance First Name before providing the list of selected contacts and the application would not be made aware of this choice. Such a decision is made in the flow of user action.

The above requires the API to be designed not only in such a manner that the user can initiate the mediation process of access to her data, but also so that it can specify which fields it claims to need.