In the real world, you don't want a program doing things without being careful. One of the more difficult things is figuring out what rules you really use for deciding what data to trust. The Semantic Web doesn't make that social problem much easier. When you have figured out a trust model, the Semantic Web allows you to write it down. Not only that -- if we introduce cryptographic built-in functions, we can actually make a system which will use public key cryptography to check the authenticity of data.

This can of course get very big, and as complicated as your social or business environment. However, we can give a taste with a simple example. The idea here is not to learn this particular cryptographic library, but to get the feel of what can be done.

Suppose we want to set up an access control system for the W3C Member site. (Yes, even though companies support W3C just because is a good thing, many quite reasonably need this "what's in it for me?" justification).

We will formalize the social arrangements and then we will write the rules which encapsulate those arrangements so that they can be followed by a machine. Let's just take the case of a web page which is only accessible to W3C members. What does that mean? Well, when a company or organization joins the W3C Advisory Committee representative is chosen as the liaison between everyone at the organization and everything happening at W3C. Currently (2003) when someone says they belong to a company and want to access the member site in that role, we check, by email, with the AC rep. Let's design a system to do it with digital signature.

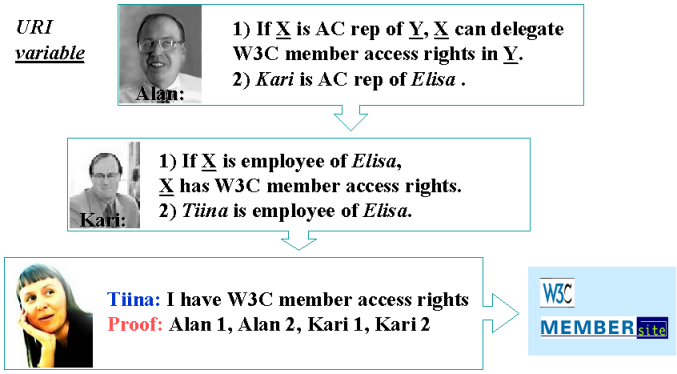

In this picture, Alan Kotok is the W3C associate chairman who deals with membership. In this case, Kari is the AC rep for W3C member Elisa Communications. Alan delegates to Kari the right to say who, as a employee of Elisa, get access to the W3C Member Site.

Alan's authority to define who is a W3C is represented by a digital key. he generates it using the command

cwm access-gen-master.n3 --think --purge > access-master.private

where the access-gen-master.n3 contains:

# Generate master key

@prefix : <#> .

@prefix log: <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/log#> .

@prefix crypto: <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/crypto#> .

@prefix string: <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/string#> .

@prefix acc: <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/test/crypto/acc.n3#>.

@forAll :x , :y.

{ :x crypto:keyLength "1024";

crypto:publicKey :y } log:implies {

:x a acc:MasterKeyPair; a acc:Secret. :y a acc:MasterKey } .

log:implies a log:Chaff.

The crypto:keyLength built-in generates :x, which a string

which actually contains both the private and the public keys. This is

convenient, as anyone who knows a private key needs to keep track of which

public key goes with it. This is not a very semantic web function, as it

isn't repeatable rule you can reuse - it is just a trick for generating a

key. (It will generate a different key each time, although the library at one

stage didn't do that to make debugging easier).

The crypto:publicKey builtin is a function which strips out

the private parts of a key :x, leaving only the public part :y. Note we have

class here :Secret which we just use for labelling things which

we don't want another person to know.

The log:Chaff part is to label those bits which are for deletion by the --purge command, just to leave the key file clean of stuff we don't want.

Kari also generates a key, which represents the authority has as Elisa's

representative. he does this in an identical fashion, using

access-gen-elisa.n3. The actual passing of authority happens

when Kari gives the public part of his key to Alan, in some way secure enough

for Alan to be sure enough it , and Alan then signs something to the effect

that it is indeed Kari's key as AC rep for Elisa.

cwm access-elisa.public access-master.private access-sign-member-cert.n3 \

--think --purge --with "Elisa" > access-eliza.cert

Here, Alan uses the private key which he (alone) has access to and the

public key which Kari gave him. access-sign-member-cert.n3 is a

rule file which does the signing. It contains, in essence:

{ :n is os:argv of "1".

:tk a acc:MemberKey.

{ :tk a acc:MemberKey;

acc:authorityName :n;

acc:junk "327462sjsdfjsakdhfkjsafd32164321"

} log:n3String :str.

:kp a acc:MasterKeyPair.

:k a acc:MasterKey.

([is crypto:md5 of :str] :kp) crypto:sign :z

} => {

:str acc:endorsement[acc:signature :z; acc:key :k

} .

:n resolves to be the name "Elisa", :tk resolves to be Elisa's public key. The string str is string form of the certificate formula, as the digital signatures work on strings. The MD5 checksum of the string is formed, and that is signed with the master key pair (:kp). All this happens as the left hand side of the rule is resolved, and when it has, then the conclusion is that that string has an endorsement which has a given signature and a given public key. This endorsement information is the certificate.

In exactly the same fashion, Tiina, the employee, makes a key, and gets a certificate from Kari about that key.

Then the time comes that Tiina wants to access the member site. She makes up a request for the web page, and signs it with her private key.

cwm access-tiina.private access-sign-request.n3 \

--think --purge --with http://www.w3.org/Member > access-1.request

The with command passes in the URI of the page she would like to access.

The crux of this whole system is the file access-rule.n3

which tells the web site how to trust a request. And the crux of that is its

first rule. It is a bit simple but you should get the idea. It says that:

if a request is supported by a key, and there is a certificate -- signed itself with k2 -- which says k is a good request key, and that there is some other certificate, signed with the master key, that says that k2 is a member key, then the request is a good request.

The other details of what "supported" means are below.

@forAll :d, :F, :G, :k, :k2, :k3, :kp, :x, :request, :sig, :str, :y , :z , :q .

# The rule of access.

#

# acc:requestSupportedBy means that it correctly claimed to be

# signed by the given key.

{ :request a acc:GoodRequest } is log:implies of

{

:request acc:forDocument :d;

acc:requestSupportedBy :k.

[] acc:certSupportedBy :k2; # Certificate

log:includes { :k a acc:RequestKey }.

[] acc:certSupportedBy [a acc:MasterKey]; # Certificate

log:includes { :k2 a acc:MemberKey }.

}.

# What is a Master key?

#

# (we could just put in the text here)

{ <access-master.public> log:semantics [

log:includes {:x a acc:MasterKey}]

} log:implies {:x a acc:MasterKey}.

# What do we belive is a request?

# We trust the command line in defining what is a request.

{ "1"!os:argv!os:baseAbsolute^log:uri log:semantics :F.

:F log:includes { :str acc:endorsement[acc:signature :sig; acc:key :k]}.

:k crypto:verify ([is crypto:md5 of :str] :sig).

:str log:parsedAsN3:G } log:implies { :G acc:requestSupportedBy :k }.

# What do we believe from a signed request?

# - what it says it is asking for.

# - what it quotes as credentials

# It could actually enclose a copy of the credentials inline,

# but here we use the web. A credential is a document which

# provides evidence in support of the request.

{:G acc:requestSupportedBy :k; log:includes {:G acc:forDocument :d}} =>

{:G acc:forDocument :d}.

{:G acc:requestSupportedBy :k; log:includes {:G acc:credential :d}} =>

{:G acc:credential :d}.

# What do we belive from a signed credential.

#

# In this case, just note that a key supports the signed formula.

# The fact of this support is used in the access rule above.

# We don't actually beleive everything the certificate says.

{ [] acc:credential [ log:semantics :F ].

:F log:includes { :str acc:endorsement[acc:signature :sig; acc:key :k]}.

:k crypto:verify ([is crypto:md5 of :str] :sig).

:str log:parsedAsN3 :G } log:implies { :G acc:certSupportedBy :k }.

The important thing is that we are really trusting very specific information from different sources.

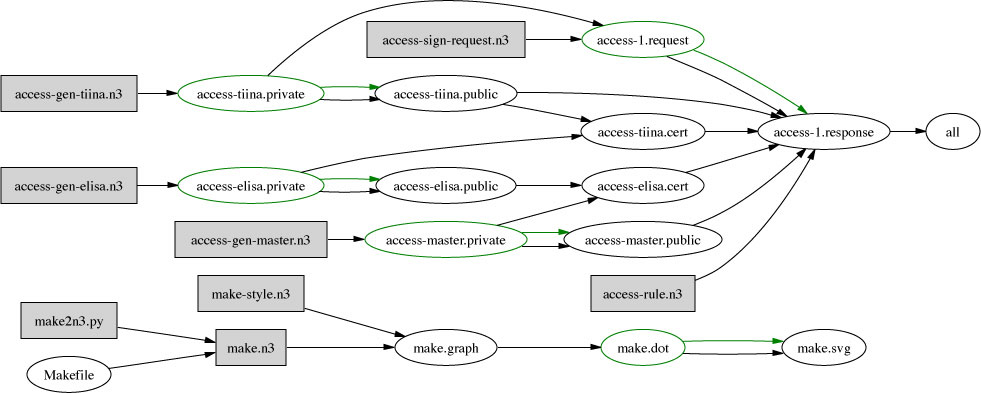

Here is the complete data flow in summary.

The bit at the bottom shows how the picture itself, make.svg,

was generated from the Makefile - via RDF of course. Some people have

actually started to use RDF just because of the diagram drawing facility, but

we hope by this stage that you will have a longer term and wider vision of

the value of Semantic Web!

You will notice that in this example we didn't use a PKI certificates looked up in a x.509 hierarchy. We could have. We would have used an RDF interface to PKI.

There are two interesting reasons not to. One is that in designing the system from scratch we defined exactly how it works. We defined what information Alan signed about Kari, without involving any other information actually identifying Kari as an individual person in the world. We don't need to know Kari's social security number with the Finnish government. The key represents Kari in the role he plays in this system. Because we are using RDF, we can put whatever information into the certificate we like. We don't have to worry about extending the certificate format. Because what we are doing concerns the relationships between the social entities involved without bringing in any superfluous external authority, it is more weblike in nature. We are freer to model the actual social trust system we use.

The other interesting point is that the amount of software for working out whether a request is valid is in fact quite small. The access rule is the secure part which is specific to this system. Apart from that the trusted code base is a general-purpose engine and a cryptographic library.

One can make the code base even smaller. Tiina can herself run the access rule herself, and generate a proof - an output of the bits of data used and rules used step by step. The web server then only has to check this proof. Although it wasn't very difficult, it did involve running a simple inference engine. Checking a proof is in fact simpler. (Cwm is being adapted to generate proofs, but it can't do it yet for this case) . We assumed that Tiina had a program to generate the request which know exactly how to do it. You could imagine a more difficult situation in which her access agent had to search for some connection between her and W3C, and find a way of justifying the request. In this case, finding the credentials could have taken a long time, or used special knowledge -- things which the web server itself wouldn't want to worry about. The proof sent would then contain just the essential information actually used to justify entry. The web server's trusted code base would be a proof checker and a digital signature validator. That's the sort of thing it every processor could have in ROM when it is made.

The ability to write rules about what document actually says what allows us to make systems which behave in predicatable and appropriate ways in the real world. Cryptography gives use the ability to build secure systems, which in a weblike way allow us to express what the real trust situation.