Figure 3. Multi-platform authoring tool based on UIML.

Submitted to W3C Workshop on Web Device Independent Authoring

Marc Abrams

Harmonia

(on leave from Computer Science Department, Virginia Tech)

abrams@uiml.org

This position paper addresses the workshop question of "whether content markup languages are adequate" for device-independent authoring. Harmonia is a company established in 1997 to develop a tool suite for the User Interface Markup Langauge (UIML). The tool suite consists of renderers for UIML documents to Java, HTML, WML (and later PalmOS and VoiceXML); a multi-platform authoring tool based on UIML; interface servlets to dynamically deliver UIML tailored to the user and device; and proxies to connect UIML to various data sources (e.g., CORBA, RMI, LDAP). Our purpose in participating in the workshop is to gauge how UIML meets the needs of other participants and areas for language refinement, as a prelude to submitting UIML to W3C as a proposed standard. The remainder of this position paper outlines the novel concepts contributed by UIML to markup langauges for building user interfaces.

The success of HTML by the mid 1990's in allowing non-programmers to design user interfaces with a rich user experience was a beacon of light to the team that designed the original UIML language: Could we start with a clean sheet of paper, and design a new declarative language powerful enough to describe user interfaces (UIs) that historically were built only in imperative programming languages and toolkits (e.g., C with X-windows, C++ with MFC, Java with AWT/Swing)? Doing so would bridge the gap between HTML, which allows easy design of UIs with limited interaction, and imperative languages, which allow design of rich UIs but only in the hands of experienced programmers. Because good programmers often know little about Human Computer Interaction methodologies, bridging the gap is important. This question lead to the first goal of UIML: to design a declarative language that could describe any UI that an imperative language could describe.

Three additional trends in 1997 influenced the UIML project. First, XML emerged as a standard representation for declarative languages. Second, the world was clearly on a trend to untether users from the desktop computer, allowing them to use a plethora of devices via growing wireless technologies. Therefore the second goal of UIML became one language to represent UIs for any device, using any language, any UI metaphor, and any operating system. Given the variety of new devices appearing on the market, UIML also had to be extensible to permit use with devices, languages, and UI metaphors not yet invented. The third trend influencing UIML was Cascading Style Sheets, which provided a mechanism to achieve a language description that was independent of the target device.

The result was the creation in January 1998 of the UIML1 language [UIML1] by Harmonia. A rendering engine for AWT/Swing was built by Harmonia and later released with source code. When the language was retired in late 1999, that renderer had be downloaded by people in over 40 countries. Also a prototype renderer for WindowsCE was built. These were demonstrated at WWW8 [ABRA99a].

As with most engineering endeavors, building the first version of something teaches you how the thing really should have been engineered. This was the case for UIML. Intensive work began in 1999 to design a second version of UIML, called UIML2 [PHAN00]. The work was done by Harmonia and in the Center for Human-Computer Interaction at Virginia Tech. The UIML2 specification was first released in Summer 1999 [UIML2], and can be freely implemented by anyone. The UIML2 specification has undergone changes in the course of implementing the language. Renderers for UIML2 have been or are being built by various organizations or people for Java AWT/Swing, HTML, WML, PalmOS, VoiceXML, the Linux QT widget set, and one embedded processor.

UIML seeks to create one canonical syntax which can represent the superset of all concepts represented by other languages for UI implementation. Doing so would simplify many things. Individuals that wanted to write UI code directly would just have to learn one syntax, UIML, and not the idiosyncrasies of N different target UI languages. Furthermore, UI implementers would be insulated from the frequent updates that are occurring to different target languages -- the tools to map UIML to target languages like HTML or Java would be updated to use features in the latest versions of those languages, and the implementers of those tools alone would be concerned with details of how to programmatically use new features in HTML or Java.

Also, multi-platform authoring tools would just need to write one syntax (UIML), which in a separate step could be mapped to any target UI language. Moreover, if all interface building tools used this single syntax as the intermediate representation of a UI, then a design created with one tool could be imported into another tool. With converters written to go from any UI language into UIML, and from UIML to any UI language, one could create a UI with a Web page design tool, save it to UIML, then import the UIML into a Java interface builder. (As a practical matter, different UI languages use different sets of widgets and UI metaphors. Therefore the process of importing a UI may involve simulating a needed widget, or may prohibit use of a widget.)

The main concepts behind UIML are presented next.

Everyone recognizes that a UI language needs to describe the presentation (its appearance or, for voice, its sound). But our view is that an ideal UI language must provide one syntax to describe three items, regardless of the target device or language: (1) presentation, (2) user interaction with the UI, and (3) connection to the things outside the UI, namely data sources and application logic.

There have been a couple of dozen attempts in the past to use markup language to define UIs (e.g., XwingML, XUL, WML, VoiceXML, SpeechML). Common to these efforts is the recognition that one could use tags like <window> to represent a widget along with a set of attributes representing presentation properties (e.g., window size, color, layout). The problem with this approach is that the tags used implicitly assume a certain UI metaphor: for example, <window> is appropriate for a desktop GUI, less useful for PDAs (whose entire screen displays one window at a time), and meaningless for a voice UI. Therefore a multi-device langauge would either require an endless number of tags, or authors would live with illogical mappings (e.g., <button> in HTML can be mapped to speech with CSS). Instead UIML describes the presentation of a UI by drawing from two powerful concepts already in W3C standards: XML and CSS.

Consider XML first. After years of battles to standardize new versions of HTML, people quickly recognized the need for a meta-language, in which the tags are defined outside the specification. XML cannot be used by itself, but only in conjunction with a vocabulary of element and attribute names (from a DTD or XML schema). In this way XML could be standardized once, XML could be "extended" an infinite number of times through new vocabularies, and tools could be built once.

The XML lesson is applied in UIML. Rather than defining tags that are specific to a particular metaphor (e.g, <window>), UIML uses about two dozen generic tags. The most important are <part> and <property>. A UI is composed of a set of parts, hence the <part> tag. Every part in a UI has presentation properties, hence the <property> tag. One cannot use UIML by itself (just as XML cannot be used by itself); one must define a vocabulary of part classes and property names outside UIML. As a consequence, vocabularies have been developed for AWT, Swing, WML, HTML, PalmOS, VoiceXML, and QT. In addition, work is under way to define a generic set of widgets for deployment to multiple platforms [ALI01]. Thus with the Swing vocabulary one defines a UI consisting of a JButton inside as JFrame as show in Figure 1. The vocabulary is exposed to the UIML author as a set of class and property names. One could represent a desired metaphor by appropriate class names. Like XML, UIML is infinitely extendable as new devices, UI languages, and UI metaphors are developed through the definition of new vocabularies.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="ISO-8859-1" ?> |

In Figure 1, how do we know that class "JFrame" maps to a javax.swing.JFrame in Java? The work on CSS and auralizing web pages provides a mechanism: a tag in HTML (e.g., H1) can be mapped to certain properties appropriate for a printed page or GUI with one style sheet, but to a certain tone voice via another style sheet. This same idea was originally used in UIML1: a CSS stylesheet was used to map a class like "JFrame" to a javax.swing.JFrame if Java was used, but then to something entirely different (e.g., a <body> tag in HTML) for another target UI language.

However, using CSS was abandon in UIML2, because the mapping needed was more complex: a class name in UIML must be mapped to either a toolkit class along with set/get properties, or to a target language tag along with attributes. Consequently UIML's <presentation> element used above refers to a file containing Figure 2. Alternately, the JButton could be mapped to <input> in an HTML document by another <d-class> element: <d-class name="JButton" maps-type="tag" maps-to="html:input">...</d-class>.

<d-class name="JButton" maps-type="method" maps-to="javax.swing.JButton"> |

|

Figure 2. Portion of uiml.org/toolkits/JavaJFC2.uiml

from Figure 1.

|

All UI markup langauges describe what widgets are used in the UI; going beyond this is where many markup languages falter. How should user interaction with the UI be represented? How should the interconnection of the UI to external entities (e.g., business logic, databases, objects, remote procedures) be represented? The landscape of UI languages contains remarkably varied answer to these questions. Added to this is the variety of ways imperative languages answer these questions. For example, the behavior that results from a button click can be represented in these ways: in HTML forms, either an attribute (action) in a tag (form) or via scripting; in Java JFC, a method call (actionEvent) in an object implementing an interface (ActionListener); and in WML, nested tags (<go> nested in <do>).

In UIML, the <behavior> element provides a single syntax to represent events for any target UI language. Drawing from rule-based systems, the <behavior> element contains a set of rules, each with a condition and an action. When the condition holds, the action is performed. Actions can set properties or call external methods. Conditions are based on events, since an event model for behavior is the most general form from investigation in the User Interface Management Systems literature.

As was the case with UI <part>s, events also are treated as class names, and thus their vocabulary is defined outside UIML. The <d-class> element specifies the mapping of event classes to class or tags in the target UI language, similar to Figure 2. A "selection" event class might be defined, mapping to a java.awt.event.ActionEvent in Java, but to OnClick in HTML. This allows UIML to be used with various types of UI metaphors and devices.

Suppose one wants to create a UI that calls CORBA objects and queries LDAP servers to provide the UI content. Suppose further that the UI will be deployed to Java, HTML, and WML. Then item (3), the description of how to connect the UI to CORBA and LDAP, would be described one time, and the rendering engines for Java, HTML, and WML would figure out how to achieve this (e.g., by using HTTP POST along with a proxy to allow HTML to call CORBA or query LDAP). UIML provides a <call> element to describe the actual connection to the entity outside the UI, and another <d-class> element (like Figure 2) defines how to resolve the <call> by giving the declaration of an external object or service interface.

When authoring multi-platform UIs, it is important to recognize that one is designing a family of UIs. Each UI exposes a different subset of functionality to a user from all the available functions of an application. In describing the UI, time is saved if elements common to multiple devices can be "factored out" and described once in a UI language. Consequently, UIML itself presumes that a family of UIs can be represented by a tree, with the description of functions common to all elements at the root, and differences between different models of devices the leaves. The tree can have an arbitrary number of levels; for example there can be a level representing different categories of devices (e.g., cell phone vs. desktop vs. PDA). Syntactically, UIML represents a tree of UIs through an inclusion mechanism that generalizes cascading in CSS. A <template> element in UIML permits reuse of interface components.

For UIML to be device independent, it must distill the "essential" elements of any user interface down to a syntactic representation. After 3.5 years of work, our belief is that specifying a UI answers five questions (corresponding to five elements of UIML2): (1) What parts comprise the UI and what is their relationship? (2) What is the presentation style for each part (rendering, font size, color, …)? (3) What is the content for each part (text, sounds, image, …)? (4) What behavior do parts have? (5) How is the UI connected to outside world (business logic, target UI toolkit objects)?

To put this five-way dichotomy in perspective, HTML mixes (1) and (3) into a single document, separates (2) if style sheets are used, relies on scripting to do (4) (except for SUBMIT buttons), and limits (5) to just HTTP operations. Another comparison is to the Model-View-Controller paradigm: (3) is the model; (1), (2), and (5) are the view; and (4) is the controller.

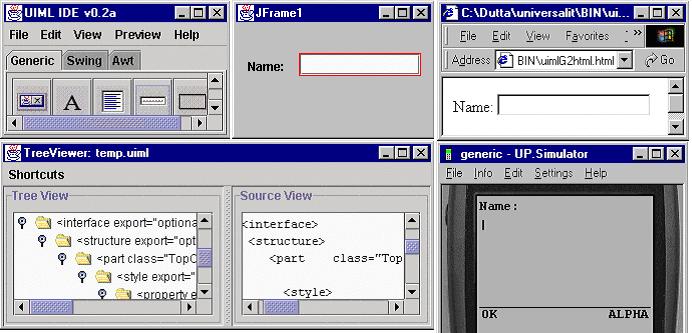

The most persuasive argument to use UIML is to facilitate multi-platform authoring tools. A vocabulary of generic UI components, properties, and behaviors for multi-platform editing has been defined [ALI01]. In addition, a multi-platform authoring tool is under development at Harmonia, based on a research project at Virginia Tech. Figure 3 illustrates the tool. The top left window shows a pallet of generic components (as well as platform-specific components from Swing an AWT), the top center window is an area to design the UI which is continually mapped to the UIML (see bottom left window), the top right is a preview of the HTML generated from the UIML in the bottom left window, and the bottom right window is a preview of the WML generated from the UIML.

Figure 3. Multi-platform authoring tool based on

UIML.

We conclude with two perspectives on UIML.

First, we view UIML as the next logical step in a progression of language development that has occurred since computing began. First people used machine language, and later assembly language, to program. Then came a miraculous day when the first high-level programming languages (ALGOL, FORTRAN, COBOL) were created. Suddenly one no longer needed to know details like the number of registers in one computer versus another to program algorithms. As time went on, scripting languages emerged to reduce the barrier for non-programmers to do a little programming. Then the device-dependent markup language HTML arrived. The ease with which UIs in the form of Web pages could be created increased the number of UI implementers in the world by one or more orders of magnitude over what had been possible with C or C++. The next logical step is to device independent markup, such as UIML. Just as high-level programming languages permitted people to author programs and leave to compilers the menial details of how to do translation to particular computer architectures, so does UIML permit people to author multi-platform UIs and leave to rendering programs menial details such as how buttons are coded in Java versus HTML 3.2 versus 4.0.

Second, a key impediment to the adoption of PCs in the late 1970's was the fact that various hardware architectures were being created, and each offered a different API to programmers. Developers could only author multi-architecture software with the emergence of operating systems (e.g., DOS, MacOS) and device drivers for PCs. Operating systems offered a common API to shield developers from hardware platforms; this produced both an explosion of software development and evolution of the hardware platform in a way that would otherwise be impossible. UIML provides a similar shield for UI implementers By analogy, today UI implementers face uncertainty and risk in adopting new devices, because of the variety of UI languages and OS APIs. To deploy a family of UIs for voice, a PDA, a desktop, and a phone, the development team would have to master perhaps VoiceXML, PDA APIs (e.g., for the Palm), Java AWT or Swing, and WML. We argue that this situation impedes rapid adoption of new devices. Just as OSs were critical to shied multi-architecture developers in the PC industry, we argue that a language like UIML is essential to speed adoption of new devices today.

[UIML1] M. Abrams, A. L. Batongbacal, C. Phanouriou, J.

E. Shuster, S. M. Williams, User

Interface Markup Language Specification, December 1997.

[UIML2] C. Phanouriou and M. Abrams, User

Interface Markup Language (UIML) Draft Specification, Document Version 17

January 2000.

[ABRA99a] M. Abrams, C. Phanouriou, A. L. Batongbacal,

S. M. Williams, J. E. Shuster, "UIML: An Appliance-independent User Interface

Language," Computer Networks 31, 1999, 1695-1708; also appeared

in Proc. 8th International World Wide Web Conference, Toronto, May 1999.

[ABRA99b] M. Abrams, C. Phanouriou, "UIML:

An XML Language for Building Device-Independent User Interfaces," Proc.

XML 99, Philadelphia," Dec. 1999.

[ALI01] M. F. Ali, M. Abrams, "Simplifying Construction

of Cross-Platform User Interfaces using UIML," submitted to UIML Europe

2000.

[PHAN00] C. Phanouriou, UIML:

A Device-Independent User Interface Markup Language, Ph.D. dissertation,

September 2000, Computer Science Dept., Virginia Tech.