iShare ~ Document Annotation and Version Control for the Internet

by

Jason Bryce Thomas

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

April 15, 1997

Copyright 1997 Jason Bryce Thomas. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce

and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part,

and to grant others the right to do so.

Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

April 15, 1997

James S. Miller

Thesis Supervisor

Frederic R. Morgenthaler

Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Theses

iShare ~ Document Annotation and Version Control for the Internet

by

Jason Bryce Thomas

jason@jasonthomas.com http://jasonthomas.com

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

April 15, 1997

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Abstract

iShare is a distributed versioning protocol that allows authors to create annotations asynchronously and in parallel with each other. These annotations are created solely on the authorís machine, and can be stored in any Internet addressable object. Authors donít need write access on the original document, donít need to communicate with each other, and donít need to communicate with a central server. The iShare protocol leverages existing Internet protocols and is implemented via an add-on the Microsoft Internet Explorer web browser.

Keywords:

Collaborative Editing, iShare, Platform for Internet Content Selection, Revision Control System, URN

Thesis Supervisor:

James S. MillerTitle:

Research Associate, World Wide Web Consortium

Acknowledgements

Many people deserve thanks for helping me through this thesis. However, since this is not an awards ceremony, I limit my gratitude to a finite number of people.

Jim Miller of MIT, who despite his many responsibilities, found the time to take me on as an advisee. Jim helped refine my ideas, correct zillions of grammatical errors, and introduced me to other people who were able to contribute.

Thomas Reardon of Microsoft, who encouraged me to expand and generalize my base idea into a general-purpose system. I also thank Thomas for his prompt email.

My family, for making sure I spent every waking moment working on this thesis.

My friends, for forcing me to hang out instead of working on this thesis.

1. Introduction

*1.1 Traditional Authoring Systems

*1.2 First Generation Web Authoring Systems

*1.3 Raison D'être

*2. Authoring Scenarios

*2.1 Cooperative Editing

*2.1.1 Group document creation

*2.1.2 Bulletin Board Systems

*2.2 Adversarial Editing

*2.2.1 Internet Rating Systems

*2.2.2 Help Systems

*2.2.3 Online Advertisements

*3. Annotation Format

*3.1 Version Numbering Scheme

*3.1.1 nHighestExistingVersion++

*3.1.2 iShare Label

*3.1.3 Constructed Parent Document

*3.2 Actual Format

*3.2.1 Standard PICS Attributes

*3.2.2 Mandatory PICS Extensions

*3.2.3 Optional PICS Extensions

*3.2.4 Assembly Instructions

*3.3 Uniform Resource Names

*3.4 Security Issues

*4. Discovery of Annotations

*4.1 PICS Based Solutions

*4.1.1 HTTP Header

*4.1.2 HTML META Tag

*4.1.2.1 Skeleton Document

*4.1.3 PICS Label Bureau

*4.2 HTTP Links

*4.2.1 Local Links

*4.2.2 Public Link Servers

*4.2.2.1 Search Engines

*4.2.2.2 Usenet

*4.2.3 Hyperlinks to Specific Versions

*4.3 Caching

*5. Implementation Issues

*5.1 Diff Tools

*5.2 Browser Component

*5.3 Editor Component

*6. Analysis of iShare Protocol

*6.1 Storage Requirements

*6.2 Performance Analysis

*7. Server Side Support

*7.1 WEBDAV

*7.2 Distribution of Load

*7.3 Non-HTML Source

*8. Comparisons with Existing Systems

*8.1 Word Processors

*8.1.1 Network Computer

*8.2 Revision Control Systems

*8.3 Usenet

*8.3.1 Storage Considerations

*8.3.2 Caching Bits

*8.4 Email Systems

*8.5 Groupware Systems

*8.6 Related Work

*9. Legal Issues

*9.1 Copyright

*9.2 Spoofing, Libel, and Slander

*9.3 Technical Solutions

*10. Conclusions

*10.1 Results

*10.2 Future Work

*10.2.1 Editing Groups

*10.2.2 Pattern Matching

*10.2.3 Embedded Data

*10.2.4 Terminal Featuritus

*11. Appendixes

*11.1 Appendix A: iShare Label BNF

*11.2 Appendix B: iShare Screen Files

*11.3 Appendix C: Example File

*11.4 Appendix D: Sample Usenet Post

*11.5 Appendix E: Contact Information

*12. References

*

List of Figures

Figure 1: Synchronous Authoring

*Figure 2: Merge Conflicts

*Figure 3: Unknown Version

*Figure 4: Numbers for Versions

*Figure 5: Distance to Root

*Figure 6: Skeleton Document

*Figure 7: Link Server Form

*Figure 8: iShare Screen 1

*Figure 9: iShare Screen 2

*Figure 10: Label Storage Requirements

*Figure 11: Disk Cluster Size

*Figure 12: Fetching and Construction

*Figure 13: Word Processor Collaboration Support

*Figure 14: Word Processor File Sizes

*

These and many other features have been grafted onto aging code bases for years. This has led to a market that judges products primarily on the sheer number of features they contain, not their size or speed. Programmers would love to stop and rewrite their code, but cannot do so because they will be passed by competitors who continue the tried and true processes of incremental improvements. This competition has also caused each vendor to re-invent the wheel rather than cooperate with each other. Consequently, software is slow, bloated, difficult to use, made from proprietary standards, and has minimal interoperability. It is crumbling under its own weight.

The Internet has blindsided developers of this old software. Thin clients, portability, open standards, and small file formats are the straws that will break its back. Developers can continue to graft features like "Save as HTML" onto their applications, but other Internet savvy are much more difficult and time consuming. The time has come where it is advantageous to rewrite systems that embrace these new standards. The first of the dinosaurs to become extinct are presentation software, and word processors; but others will follow.

Startup companies beat the big software houses to the Internet. Their software was written from the ground up to support the Internet standards such as HTML and HTTP. Although this software does not have feature parity with its traditional counterparts, it is better suited for Web development.

This does not mean that these new systems are without problems of their own, or that they have solved, or even attacked all the problems of the Internet. The first problem is that the authoring tools are not always the viewing tools. This means that while one may edit their document in Microsoft FrontPage, or AOL Press, one must tweak it to match the characteristics of the two web browsers used by 95% of the market. A shakedown is about to happen as Netscape and Microsoft introduce capable editors in version four of Navigator and Internet Explorer. As for the general spirit of Internet applications, developers are hard at work on interoperability and portability. Programs are just being introduced that allow authors to uniformly save documents to their local storage, their Intranet, or to the Internet.

The second generation of web authoring systems must capitalize on the new opportunities enabled by the Internet. These include better collaboration routines in terms of authoring and voting systems. They also include more advanced agent and filtering technologies to sort the abundance of data, not just stale bandwidth clogging push technologies.

The rapid improvement of Internet protocols combined with the progress of Web authoring systems make it clear that they will replace traditional authoring system. But alas, Microsoft need not worry about shrinking sales of its Office product for a couple of years; the time it will take to gain total feature parity. The areas in which Web programs most lag their traditional counterparts are collaboration and version control. Due to time constraints, this thesis is focused on the latter issue.

I have attacked this problem of version control for HTML documents on the Internet by creating a protocol called iShare. iShare is a revision control language, which works in conjunction with HTML, to allow authors to embed multiple versions of their document in either the original file, or elsewhere on the Internet. This protocol was designed with the idea that Web servers are overburdened, that some authors may have low bandwidth channels, or even be disconnected, and that authoring will continue to move towards GUI tools. Authors modify their file as normal, when complete, the iShare enabled tool will package their work in the form of a delta which can be posted to any web server, and viewed with the original document.

iShare is designed to work with the existing infrastructure of the Web. The only protocol I modified was the Platform for Internet Content Selection Label system, which was done via its built in extension system. Processor intensive tasks are done by the editors on their private machines, before the annotations are posted, and by the viewers, when they read the document. Other than serving the annotations, no extra processing is done on the server. Furthermore, iShare requires neither handshaking protocols among the authors, nor state (found in Web NFS, Common Internet File System, and WEBDAV), which can become inconsistent. This means people can work off-line and need only send a limited amount of information over low bandwidth connections.

I have written a Microsoft Internet Explorer extension to fetch and view iShare documents, and a command line utility to create iShare labels. See Appendix E: Contact Information, for availability of the source and executables for these programs.

Group document creation systems allow a connected group of people to edit a single document. At any time, any author should be able to view any version of a specific document, make changes, and then commit their changes so that the other authors can see their work. Indeed, traditional revision control systems (RCS) give us these capabilities by dedicating a server to preside over requests to read a specific version of a document and to update its contents. An example of this system is below.

After he is finished his draft, Ben sends the entire document to the RCS for storage then asks Alyssa to proofread it. Alyssa tells the RCS that she wants to read the latest version of this document. She reads it over, finds and corrects Benís fundamental reasoning errors, then submits the modified document to be stored. RCS then computes and saves the delta between the most recent stored version of the document and Alyssa's new version, then releases Alyssaís lock [].

This situation breeds a number of scenarios. The first is that after she has finished editing the document, Alyssa tells Ben she is finished. Ben then contacts the RCS for the new version of the document, checks it out, makes his final revisions, and sends the master to the printer (see Figure 1).

A second scenario is that since Ben waited until the last minute to start this presentation, he continues editing the document while Alyssa corrects mistakes from the first draft. When Alyssa commits her changes, she is notified by RCS that Ben is currently working on the document, then calls Ben. Ben asks RCS to merge the latest changes with his private uncommitted version. He grumbles about the fact that Alyssa had completely re-written the section he had just finished, fixes the conflicts, then continues his work. Alternatively, Ben could have committed his changes before Alyssa had finished, then Alyssa would have worried about fixing the conflicts (see Figure 2).

The third scenario is where Ben checks out the document while Alyssa is editing it. Alyssa commits her changes. Then Ben commits his without noticing that Alyssa had committed a version in the interim. Ben has now lost all the work Alyssa had done. A typical RCS system would notify Ben before he saved his version. However, had Ben missed that message and saved his changes, he would be able to reconstruct Alyssaís version later (see Figure 3).

All is great if neither the RCS system, nor the client systems freeze and lose state while a file is locked. Unfortunately, both occur today with closed networks, and are exaggerated when RCS is extended across the Internet. Nonetheless, work is being done to extend the HTTP protocol with file locking functions []. This solution has a number of flaws. First, it introduces state to an otherwise stateless protocol. It requires changes to both clients and servers. It only works with HTTP, meaning that we will have to re-invent a solution if we choose to move to potentially faster protocols such as Web NFS. Finally, it is impractical to require low bandwidth editors to send the entire document across the network for a few minor changes. The Distributed Authoring Scenario document proposes to solve this by sending only the delta across the network []. The server either stores this delta in the tree, or reconstructs the final document, and stores this. Unfortunately, changes to both client and servers are needed to support this new protocol, authors are required to have write access on the host server, and this protocol places a processing burden on the server.

Had Alyssa and Ben been forced to edit without an RCS, they would need to be extra careful to not to edit the document at the same time. There are no means to merge the changes, and they could blindly overwrite a version of the document of which they were not aware. Finally, they still have the bandwidth problem.

In designing iShare, I assume the authors have very limited opportunity for out of band communications, have no access to an RCS system, and may not have write access to the same file system. Therefore, the iShare protocol specifies that the delta and version numbers are created solely on the client machine, and the output posted to a standard web server.

Bulletin boards (the most popular of which is the Usenet) are systems that allow users to comment on and extend a central topic. To write a follow up message for the Usenet, Ben composes his message on his local machine then sends it to his local News Server. At regular intervals, his news server exchanges messages with other news servers, and Ben's message will eventually be copied to Alyssa's news server.

The iShare system is similar to Usenet in that both are distributed discussion groups where authors post messages to different machines without actively cooperating. iShare messages require less storage than do Usenet messages because iShare messages are not replicated across multiple servers. The delta nature of iShare messages improves the storage efficiency since most replies quote the parent message.

Adversarial editing is the ability to make changes to a document without modifying the original data. The original document is stored in a file on one server, and its annotation in another file, or on another server altogether. When given a reference to this annotation, the UA is responsible for fetching both the original document and the annotation, and then constructing the final version. This gives Alyssa the ability to annotate Benís document although she doesnít have write access on Benís server (unless sheís an expert hacker).

Internet Rating SystemsAn example of using adversarial editing occurs with the Platform for Internet Content Selection (PICS) Internet Rating System. The PICS specification allows independent groups to rate the content of web documents. Parents can then configure their web browser to contact the independent rating group of their choice, and filter the pages depending on constraints of the groups they have chosen. In some cases, the group might find a page very valuable for its target audience, but object to the page due to a small passage. iShare allows them to post their modifications along with a revised rating. The UA will display the amended document instead of blocking the original.

A second use of adversarial editing is to open and extend proprietary help formats. Windows Help is currently a proprietary hypertext help system that allows users to annotate help pages with personal comments. Microsoft has announced plans to move this to an HTML based system []. When this happens, one will be able to use adversarial editing not only to write personal comments, but also to store tips for all members of the group. For instance, after finding a bug in a Win32 API under Windows 95, a programmer could document this bug for the group to read. He could also use these facilities to document his groupís programming conventions in places like a Java programming guide.

A third example of adversarial editing is the elimination of online advertisements. One could conceive of a service that went to each major web site and created annotations that would prevent web browsers from requesting advertising banners or displaying blinking text. Indeed, a company called PrivNet produces a plug-in whose function is exactly that I described []. This application of the iShare technology introduces many legal questions relating to copyright violations. It's also dangerous to the web because it potentially reduces the amount of advertising money a site can collect, thereby making it more difficult for web site to sustain themselves [].

In order to leverage existing standards, iShare uses the PICS Label specification as a base for its annotation format. PICS Labels allow authors to specify personal information such as contact information, date of modification, and comments along with the rating. This specification also describes how to store PICS labels into HTML documents, HTTP headers, and inside external PICS Label Bureaus. Most importantly, this specification has an extensions system that gracefully degrades [].

Version Numbering Scheme

It is important to compare the difference between version numbers with connotations for humans, and those meant solely for machines. Version numbers for humans are frequently written in a dotted pair notation (i.e. version 3.1). The left side indicates the major version, and the right side, the minor number. A change in the major number indicates a large difference or even incompatibility with a resource containing a different major number, in terms of document annotation, a complete re-write. A change in the minor version number typically indicates a small change or spelling mistake.

iShare labels are meant to be read by computers, not humans, so we need not graft human connotations into the version number scheme. Since iShare indexes files with a byte offset from the start of the document, no matter how small the change, each iShare label must contain a distinct version number. Information containing reasons for the new version can be preserved through comment fields in the iShare label. Through use of these fields, iShare can present the user with recognizable version numbers. This information allows user directed crawlers to suppress notification of document changes for minor corrections.

nHighestExistingVersion++A first shot at making version numbers is to derive the correct number from the version number of existing annotations. If the parent document has no children, take its version number and append ".1." If it has children, find the one with the highest version number, and increase the last digit (see Figure 4). Unfortunately, this goes against the design criteria that labels can be created in isolation. If one went ahead and employed this scheme anyway, multiple annotations could share the same version number Ė a condition that makes it impossible for the UA to reconstruct the correct tree after annotations to these annotations have been created.

A safe method that an author could use to generate version numbers is to hash the parent annotation. In the case where the parent is the original document, this, not the label would be the hash. Now, clients who make the tree could easily organize it by computing the hash for each part, then sorting. The problem with this system is that it prohibits us from collapsing multiple annotations into a single annotation for administrative reasons when the tree becomes long or retrieval time too long.

The language used to describe the iShare system is a superset of the one used for PICS 1.1 Labels. Since iShare labels contain a new mandatory PICS extension, UAs that just support PICS will recognize these as unreadable, and proceed to the next label.

The guts of the extensions are the annotation commands insert and delete. In this version of the specification, all annotation commands operate on byte offsets from the start of the document. I also define filters one applies to the documents before computing the delta. These minimize unintended conflicts that could occur from the standard editing process. An example of this occurs when an author creates the original document using a text editor, and a subsequent one uses an HTML GUI editor. When saving the document, HTML editors typically insert, remove, reorder, or change the capitalization of HTML tags and attributes that don't affect the viewable output. If we use a filter to canonicalize the HTML document, many of these unintended conflicts can be avoided. The optional extensions are present to improve the efficiency of document construction.

Excluding the MD5 and Signature fields of a PICS label, neither of which are used in current implementations of the PICS specification, ordinary people can generate and decipher PICS labels. Indeed, this is the mantra of HTML, a text based standard. Unfortunately, this is not the case with iShare labels. Not only is it mandatory to include the version information in iShare documents, due to the PICS extension format, it is necessary to encode some characters of the inserted text. I have written a command line tool that generates iShare labels from an original and modified document. Besides, with the exception of a few holdouts who enjoy hand coding HTML, most authors will use GUI tools to do so in the near future.

Standard PICS AttributesThe PICS label grammar specifies that a

serviceID and the rating of a single attribute must be present in each non-error PICS label. Since many people won't take the trouble of rating a document, I define a NULL rating system. The serviceID for this system is "NULL" the transmit-name and transmit-number are both "0" without the quotes. iShare agents encountering this rating will treat the document as if it were not rated.

Other options such as comment, on, by, and the signature are encouraged, but not required. Authors of the master document who want this information can encode their master document in the form of an iShare annotation of a NULL document. Alternatively, if the base document is HTML, include this information in META tags in their HTML. Key features of the iShare Label syntax are listed below Ė a full description is found in Appendix A: iShare Label BNF.

The format required by the PICS Label syntax for mandatory extensions is

"

iShare 1.0 compatible clients are expected to support each mandatory extension that is described in this document, whether or not they are likely to be present. Clients are required to disregard both ill-formed labels and labels with unknown mandatory extensions. Custom applications extending iShare should store data using the standard PICS extension process, not the extra data fields in the iShare extension.

I define two different optional extensions for the PICS specification. The first contains information on the editing group and user defined flags. The editing group is a list of identifiers of people who are authorized to publish subsequent annotations. This means that the Webmaster of ESPNet site might allow each contributing editor to post new columns off the main page. The UA may have an option to display annotations from authorized editors as part of the original document. The section on flags allows one to include human readable names, and URLs for extended explanations for application specific flags.

In the second optional extension, I provide space for the authors to list possible locations of other annotations within the tree (this is especially important since this information is not given in the version). Since the parent annotation may move, it is important to update this field after the label has been produced. Unfortunately, doing so would break the label's signature. I will propose an addition to the upcoming PICS 1.2 specification that will let us get around this constraint. The new extension system would be as follows:

After collecting the original document and each annotation, construction is straightforward. For instance, to construct version 1.1 from Figure 4, open the root document, the 1.1 annotation, and create a new destination document. Query the annotation for the first amendment, noting the character position on which it operates. Copy the text of the root document from the current file pointer to the character position onto the destination. If the amend operation was a deletion, advance the file pointer of the root document the appropriate number of spaces. Otherwise the operation is an insertion, copy the inserted text from the annotation into the blank document. Repeat until there are no more operations to perform and the file pointer of the root document equals end of file.

The Network Working Group proposed criteria for a new Internet resource naming scheme called Uniform Resource Names (URN) []. These differ from Uniform Resource Locators (URL) in that URNs describe a unique name for each Internet resource that does not necessarily imply the location of the document. In fact, most proposed URN implementations rely on a service that will convert URNs into URLs. The point of this added layer of indirection is to allow authors to move a document without breaking existing hyperlinks that reference it.

iShare labels reference other labels via a version number, which is an encoded hash of that documentís contents computed by the labelís author. This satisfies the requirements for URNs: have global scope and uniqueness, are persistent and scaleable, have a single encoding, simple comparison, transcribable by humans, and parseable by machines. The mapping from a URN to a URL is based on a heuristic that checks the hint section and

for field of the iShare label, and external sites that may store the URL for a version. Except the for field, these can change after the label is created. This satisfies the resolution requirement of RFC 1737, and the premise that the mapping from an URN to a URL can change at any moment.

Although iShare seems to be a reasonable attempt at the creation of a URN system, this is purely coincidental. iShare employs URN capabilities to support external labels in general, and adversarial editing, where the annotation authors may need to replicate the original document after the label has been deployed. The essential function iShare lacks are a deterministic method for the mapping from URN to URL, and support for legacy systems.

Already it is required that the hash of the parent document be included in the iShare label. This ensures the viewer that the author of the label intended to create his label on the document he specified. If someone changes that document, his edits are not applicable. As previously stated, I encourage all authors to include information such as their name, and the time on which they created the annotation. But the most powerful technique is for the author to digitally sign the label with their public key. This means that one can detect if the label has been corrupted. The only part of the label that is not included in the signature is optional extensions containing the

nocrypto flag. It is valid for these to remain in the clear, as their presence does not affect the correctness of the system. Refer to the PICS Label document for further information relating to the signing of labels, as there are no tangible differences between iShare and PICS labels that are affected by a digital signature.

Microsoft Internet Explorer prioritizes ratings from four different sources. In order of precedence of reliability, these are: local exclusion list, PICS label server, HTTP header, and HTML META tag. The rating from the most reliable source is used, and operations to obtain information from lower sources in the list are canceled. If the UA downloads an iShare label, it would not understand the mandatory extension, and thus discard the label. iShare compliant UAs should search each PICS location for iShare labels.

HTTP HeaderThe PICS label specification says that a web server can transmit a PICS label to a browser by inserting the label into the HTTP header when transmitting the document. The syntax of this is "

PICS-Label : <labellist>" []. iShare labels transmitted in the HTTP header use an identical syntax.

If an author has control of their web server and all his pages are identically rated, he may consider embedding the rating inside the HTTP header. This allows him to store the ratings in a global database as opposed to storing identical ratings in each document. This transmission technique is efficient since ratings are not sent to UAs that do not request them. An Internet Service Provider (ISP) may choose this technique to rate his usersí pages that are a liability.

This method could be useful if the server is connected to robot that finds annotations stored on other servers. It could also be useful to store annotation in a central database rather than directly in a file system. For a client, sending labels this way is harmful since most browsers don't cache header information.

Most authors who rate their own content, do so by including the rating in the HTML document within a META tag, the definition for which is "

<META http-equiv="PICS-Label" content='labellist'>". These are expected to appear within the HEAD tag. Again, this is identical to that used with iShare labels. Occurrences of singe quote, ampersand, and greater than symbol that appear within labellist are encoded respectively as ', &, and >. As previously mentioned, one can store annotation within the base document after the document has been published. Skeleton DocumentOne can store an iShare label in an external HTML document. This is done by creating an empty HTML document and including the same META tag one would use if you included the annotation with the original file. Likewise, one can include multiple iShare labels as META tags inside any HTML document. Storing iShare labels inside of blank HTML documents makes them more accessible to search engines than if they were stored inside of a label bureau. To provide graceful degradation in case one without iShare inadvertently stumbles across such a document, I suggest you use the shim as in Figure 6, and use the file extension

.is.A more graceful solution is to provide a mechanism within a single file whereby non-iShare users can see the most recent version of a document, and iShare users are able to see a complete version history. This can be achieved by first converting the original document to an iShare label (the un-encoded version number is 0). Next, storing this label, as well as subsequent labels as META information inside of a document whose body is the final version.

The final technique to retrieve a PICS label is to do so by storing it inside of an external PICS label bureau. When the browser requests the userís page, simultaneously, it asks a PICS label bureau for the documentís rating.

When requesting a label from an external label bureau, the user can request a number of different formats for the label. The two base ones are minimal and full. As implied by the keyword, minimal labels contain only the base amount of information, like the rating and for field, whereas full labels contain information like the hash and digital signatures. The point of this differentiation was so that bandwidth constrained clients need only receive a small amount of data. Current rating bureaus do not sign labels anyway, so this measure was meant for the future, at which time everyone will have the bandwidth for the extra hundred or so bytes anyway.

Another option one can specify is to ask for generic labels. A generic label contains the rating for all labels beneath the desired branch. When using standard PICS labels, this is important because the UA can request a single generic label, and then would not need to request further labels for that site. This option is useless for iShare, which has no concept of generic labels.

The most meaningful option is tree, which allows the browser to request all the labels that apply to items in a site or subpart of a site. For large sites that have many annotations, transferring each annotation for every document is prohibitive. PICS label bureau masters should note this when honoring such requests if they store iShare labels too, for non-iShare browsers would get a slew of meaningless data (similar for the option

generic+tree). One solution to this problem is to have different service URL for iShare labels than PICS labels. The other is for the server not to return PICS labels containing mandatory extensions if the extension name is not specified in the query.

HTTP 1.1 includes a new protocol for linking two URLs and stating their relationship. One can embed a link inside of the source HTML file, or store it in an external HTML file. Likewise, HTTP 1.1 provides a naming convention for external link files and defines new methods used to query links. The value in a link is tied to a common understanding of relationship types. For instance, a UA may pre-fetch pages whose relationship to the current page is of type "next." I define the name "iShareA" to mean that URL A is in the annotation tree of URL B.

Local LinksAdministrators of servers that house all versions of a document can help iShare users by creating a link from the base document to the most recent annotation. This allows the administrator to store the most recent version of the document as a traditional HTML document accessible to all clients. The link will help iShare compatible clients locate the rest of the version tree.

A second use of links are to aid the UA in finding annotations that donít reside on the same servers as does the original document. A public link server is a robot that scours the Internet looking for these relationships. Alternatively, it can take record this information as standard user input. For instance, an author of an adversarial annotation might input this information to the link server via a form (see Figure 7). If the UA is set to query the public link server each time it fetches a URL, it can find the locations of these remote annotations and build a tree. Known as distributed link servers, these exist today [], but the interfaces vary between implementations.

Search Engines

It seems natural to extend search engines like Alta Vista, Lycos, and Infoseek to include the features of a public link server. The first change would be to embed the links in a link tag after the hyperlink to the found document. The second is to implement an industry standard interface that allows the UA to seamlessly query the search engine for this information. For this to be profitable, the UA might display a search engine advertisement in the index pane.

Even if search engines arenít retrofitted to provide aid in the discovery of labels, the proliferation of iShare labels will require modifications to search engines anyway. Search engines need the ability to construct a document from its iShare label so that it iShare labels can be searched and cataloged in the same manner as standard HTML documents.

One could create a Usenet newsgroup "

news:alt.ishare.labels" dedicated to the storage of these iShare links. The title of the message contains the URL of the source document, and that of the iShare annotation. The body of the message is empty. At startup, the UA downloads the index file for this newsgroup, reconciles it with a cached copy, then downloads the new links.

The first drawback to this system is that the message base could become swamped with new links, and the download time would become prohibitive. The second problem is that when the message expires, information about the link is lost.

The next step in defining the iShare system is to include a mechanism by which authors can create a hyperlink to a specific annotation as opposed to the original document. This is done by extending the HTML anchor element to include a new attribute called version. For example, if an author wishes to link to a specific version of a document, he writes the following HTML

To speed in the construction of the document, the author will also want to include the location of

Vn along with other versions that appear in the iShare tree. He does this by following the anchor with a number a link element for each iShare annotation in that tree. For example:Since it can be time consuming to search for annotations each time you read a document, the should UA cache the location of annotations as they are found. It would be easy to store these in the same file where Favorites or Bookmarks are kept. Browser vendors need to weigh the costs of storing this information for all HTML pages that are in the cache or history lists against the potential speed improvements.

Of course, users, especially those on the same local network, should be able to subscribe to each otherís list of Favorites, providing, of course they have permission to do so. When the browser starts up, it could scan the other Favorite files for the locations of the most recent annotations its user was monitoring. This process should be accessible without the need of a separate server application, as is described in []. Although the format of bookmark files varies across UAís today, the web collections proposal standardizes this file [].

While robust, my implementation of iShare is a proof of concept design that was built to iron out design issues and test key assumptions. Right now, the browser component is an executable file invoked through URL associations in the registry that communicates with the Microsoft Internet Explorer 3.0 web browser via DDE. The editing component is a command line application that constructs the iShare label. In this section, I will explain why it is important for these pieces to be integrated with the Web Browser and HTML Editor.

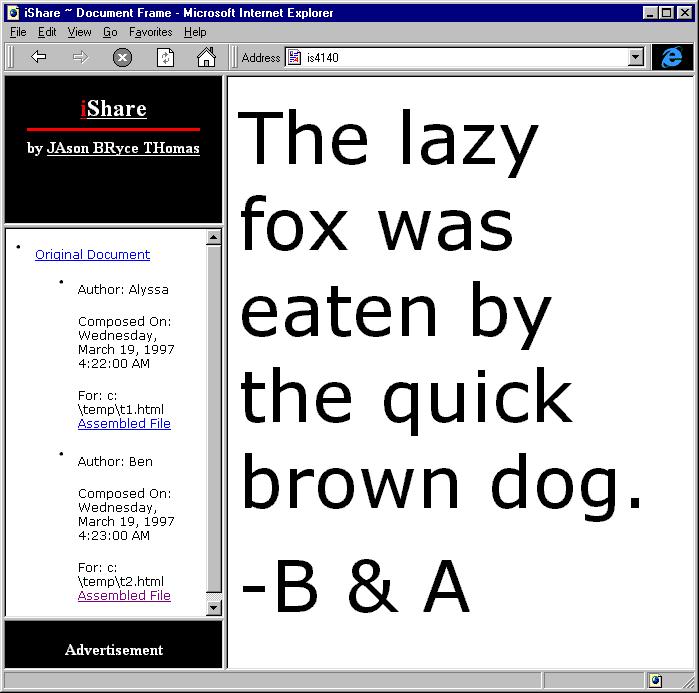

Screen shots of an iShare in action is shown in Figure 8 and in Figure 9. The sample files used to create these runs are found in Appendix B: iShare Screen Files.

Diff ToolsThe core of the label generation portion of iShare relies on the Free Software Foundation version of diff. This tools takes two text files as input, and lists the changes necessary to convert one to another in terms of insert and delete commands that operate on entire lines. This means that a single character change will result in a new copy of the line, instead of the offending character. A smart implementation of the label constructor will perform post processing on this output to reduce the redundancy.

The current implementation of the label constructor invokes diff by spawning a process, blocking until the return, then operating on the result. Obviously this hack cannot be used in a commercial implementation that canít waste the time spawning a process and doesnít want separate applications on the userís system. Directly compiling the source into your program wastes space, (There is a bunch of unneeded command line options. Some however, make useful filters, such as white-space removal, tab expansion, and case sensitivity) and results in Copyleft problems of the GNU licensing agreement [].

Implementers should always be wary of the end of line compatibility problems between UNIX and DOS. UNIX systems demark the end of line with the character 0xD, while DOS uses the sequence 0xA 0XD. Problems occur when an author creates a document on a UNIX system then edits it on a Windows platform, or vice-versa.

I chose to implement the browser component of the iShare as an external application because it was the easiest way to create seamless integration with the browser. This application is invoked when the browser encounters any URL starting with "

istp:". The application receives the full URL, then returns the results to the browser via DDE. This integration technique is compatible with Microsoft Internet Explorer 3.0 via registry settings for URL handlers and with Netscape Navigator via a DDE server.

The first problem with this approach is that the web browser does not allow applications to take over the

http protocol, meaning iShare cannot find annotations for existing documents which may have external annotations. Had I implemented iShare as a proxy server, this problem would not exist.

A second, more serious problem relates to the performance of iShare. An implementation either as a proxy server or as a plug-in to URL moniker results in synchronous operation. The user must sit and watch a spinning globe while iShare downloads the requested page, looks for and downloads annotations, then constructs the index. I have tried to reduce this time by allowing HTML authors to include the locations of known iShare labels within the hyperlink. This allows the iShare program to begin downloading labels in parallel along with the original document. Instead, the original URL should appear in a frame as is done today, while the index is being constructed on another thread that updates a second frame as a background task. A hack to simulate this feature is to use either client pull or server push on the index frame.

The third problem deals with the redundancy of parsing label code. A PICS enabled web browser already scans through the HTTP headers, HTML code, and consults external label bureaus to find PICS information. This iShare implementation must repeat this work since the browser does not export code to do this. Obviously this bloats the iShare code and slows construction of the final document. External iShare implementations must also ensure that constructed pages that have improper ratings cannot be viewed by unauthorized viewers (this means deleting the temporary files after subsequent ones with proper access are created).

If Microsoft gets smart and decides to integrate URL moniker with the CreateFile API and standard file dialog boxes, loading from and saving to HTTP servers would become transparent to existing programs. Thus by integrating iShare into URL moniker, these applications could understand iShare documents as well. More important, since Microsoft is pushing structured storage for all documents in its file systems, it could develop a filter that understands iShare annotations.

I created a command line tool that helps one construct iShare labels. As input, this tool accepts the paths of a base and modified file, and the name of the author. It outputs two copies of the corresponding iShare label, one in a pure format, the other embedded in a META tag. One can extend this simple tool by adding command line switches to include the other optional parameters, and search external files like the system registry for the authorís private encryption key.

If the interface was extended to scan environment variables, a smart web browser could invoke this as a CGI script to return smaller information on-the-fly for low bandwidth users who have downloaded similar documents during the session. For this mechanism to work, the browser would need to add an "

ACCEPT: iShare" to its list of HTTP headers. Then again, any server wanting to do this would generate these labels (once and for all), on its own time.

While power users are probably happy with label generation as a command line tool, it is clearly not suited for the majority of users who code HTML with GUI tools. The base scenario is that the editor would give the user the option of saving their document as an iShare label or as an HTML document. It could also include a wizard that prompts them for PICS labels such as those from the RSAC system [].

The most important reason for integrating iShare into HTML editors is to solve the problem of relative hyperlink references. The editor can simply include a "

BASE" tag referencing the original web page after the "HTML" tag. Integration with an editor also provides a more meaningful delta, and can prompt the user for comments on each change, a function more difficult with command line tools.The storage requirement and performance of the iShare protocol is analyzed in the following sections. This analysis is based on an efficient ideal implementation of the iShare protocol, not a simulation based on the reference implementation.

Storage RequirementsWhat is the overhead in storing an annotation inside an iShare label? Should I have adopted a completely new binary format instead of one based on the PICS label specification? Is the overhead prohibitive for small documents, large ones, or ones that require many changes? The table in Figure 10 tries to answer some of these questions by comparing the size of an annotation stored inside of a minimal iShare label, and that of a purely binary format.

|

Format |

Deletions1 |

Insertions2 |

Version3 |

Extras4 |

Totals |

|

Binary |

d*9 |

i*9 + å dataI |

16 |

0 |

16+d*9+i*9+å datai |

|

iShare |

d*19 |

i*19 + å (datai + encodingi ) |

28 |

69 |

97+d*19+å (datai + encodingi ) |

|

Delta |

d*10 |

i*10 + å encodingi |

12 |

69 |

81+å encodingi |

1 - ('d',start,stop)

2 - ('i', start, len, data)

3 - (hash)

4 - "(PICS-1.1Ö)", "r (0 0) " "extension (mandatory "http://ishare.com/em.html" Ö)"

This table shows that we have an overhead of approximately 97 bytes each time we create an annotation. This number increases as we add identifying information like the author's name, date of the annotation, and comment of the changes. The order of growth of the size of these labels is linear in regard to the number of insertions and deletions, and is dominated by the number of insertions. This means that the only important overhead in choosing the PICS label format over a binary one is in the size of the encoding.

The Web Consortium released a brief study showing typical compression rates for compressing HTML documents []. The tested documents shrunk to about 30%. A small test puts the compression rate of iShare labels at about 50% (see Appendix B: iShare Screen Files). The study stressed the importance of printing HTML tags in lowercase, as this would shrink the size of the compression dictionary. This also reiterates the need to create a strong HTML canonicalization filter for use with iShare.

Most file systems divide the disk into units called clusters. Files are written across multiple clusters, but each cluster can contain at most one file. This means half of the space in a file's final cluster is unused, which for advanced file systems is typically 2048 bytes. This means that for small modifications, it takes no extra space to house a few small changes, whereas if these changes were to be stored as a separate document, the storage would be doubled. Unfortunately, the cost comes in transfer time, as TCP/IP packets are of variable size.

|

Partition Size |

Cluster Size |

||

|

FAT |

FAT32 |

NTFS1 |

|

|

512-1023MB |

16KB |

4KB |

1KB |

|

1024-2047 |

32KB |

4KB |

2KB |

|

2048-8GB |

NA |

4KB |

4KB |

|

>8GB |

NA |

8KB Ė 32KB |

4KB |

1. Files under about 2K are stored in the directory entry.

Figure 12 shows a graph of the time-based dependencies that occur when constructing an iShare document. The four different bars are: a standard HTML document, an iShare document, an standard HTML document whose rating must be checked from an external label bureau, and a reverse iShare document. As can be seen, progressive rendering is nearly destroyed when requesting a rating from a label bureau, and is completely ruined when one hyperlinks to an iShare annotation.

It is common for web sites dependent on advertising money to tag their pages with the NO-CACHE option. This forces the UA to reload the page (which differs from the original by the URL to the banner ad) each time the page is visited; not just the first time. Instead of reloading the entire page, these sites could send the users an iShare label that details this change. Of course, for this to work, the UA would have to understand a new header specifying this behavior.

The Web Consortium also reported that using HTTP 1.1, PNG, and CSS increased performance by a factor of 2 to 8 []. Developers implementing a reverse iShare systems should refer to this study in terms of overlapping requests and should poll for the bandwidth of the connection. For low bandwidth connections it is beneficial to postpone the download of iShare labels for reverse iShare systems.

iShare has been described in a setting where the client was completely responsible for the storage and assembly of the document tree. Indeed, two goals of this project are that all processing is done on the client, and that existing web protocols are preserved. However, the presence of either an administrator or enhanced protocols on the server makes the iShare protocol more efficient and accurate.

While iShare might become popular on the Internet as a replacement to Web based threads, it should blossom in small companies as a groupware solution. These small companies are moving to construct Intranets but have yet to embrace groupware software like Lotus Notes or Microsoft Exchange, which are considered heavyweight, expensive, and difficult solutions. In contrast, although not necessarily valid, web servers are considered lightweight, cheap, and easy to manage. Intranet users should have write access to a common server and have strong out of band communication, something lacking of Internet users.

WEBDAVWorld Wide Web Distributive Authoring and Versioning (WEBDAV) is an IETF working group charged with extending the HTTP 1.1 protocol to include support for Distributive Authoring and Versioning []. The focus of this group is to add new methods and protocols in such a way that existing version control systems can be grafted onto the back end of web servers. Clients with authoring tools, like AOL Press, communicate with these new interfaces.

At the outset, the only similarities between iShare and WEBDAV are that both are concerned with distributive authoring and version control, and that both benefit from the Web Collections protocol. A typical scenario is that a client creates version 2 of a document then saves the resulting iShare label to the host server. Ideally, an administator will embed this label inside the original document. However, if both the client and server support WEBDAV, and the client supports iShare, the client can perform the administration himself by storing the label, executing a merge command, then deleting the label. When used in this form, the advantage of iShare is that it provides a consistent interface to the viewer, and that it reduces the amount of data thatís sent across the network.

In a departure from traditional web protocols, the current WEBDAV protocol includes little mention of support for syntax errors, stating that both the client and server should be capable of generating correct messages. This trend will help transform web protocols from a text to a binary standard.

With the cooperation of a web server, one can provide additional support for down-level clients, and make tradeoffs affecting the distribution of load. With a special server version of iShare, the server can construct and return the document index to clients immediately. The server can also return the fully constructed requested version of the document. This saves the user in fetching time, and caching, since the server can cache the document index. Depending on the current server load and state of the network, iShare capable browsers might prefer the server do this construction.

Not all data presented as HTML is actually stored in this format. Increasingly, data is coming from SQL databases and other sources that are converted to HTML when the user requests the document []. Even when itís possible to retrieve the complete data set in native form, iShare is not the best versioning protocol for this medium. Instead, routines constructed for this proprietary format should be used so that it can be manipulated within the host application. The advantage to using iShare is to present the viewer with a consistent interface.

Web browsers are quickly becoming the generic interface to view all files. As HTML is becoming more rich, and editing tools advance, it is apparent that HTML will replace proprietary file and viewing formats such as those used in: Word, Excel, Acrobat, email, and news. Indeed, Microsoft has vowed to make HTML its native file format. In order for this vision to succeed, HTML must gain tools such that programs which adopt it will be able to support all of their existing features while retaining comparable performance.

Modern Word Processors, Revision Control Systems, public message bases, email systems, and groupware products contain versioning capabilities and collaboration features. These systems are related in that they are either coming under attack from standard based systems, or their functionality is being merged with other systems. In the next few sections, I compare these systems with a hypothetical system one could create using iShare, WEBDAV, and HTML 3.2.

Word ProcessorsThe last generations of word processors added collaborative editing features. Add-ins have been developed, and subsequently incorporated into the main program that converts the native file formats into HTML for display on the Web. This new generation of word processors from Microsoft and Lotus have even more collaboration features and Web support.

These traditional programs are being attacked by graphical HTML editors. GNN Press, PageMill, and HotDog Pro, operate directly on HTML rather than a proprietary format, and have even more net-centric features than are found in standard word processors. Software like FrontPage and SiteMill are trying to create a separate niche market by bundling web site management functions as well as authoring ones.

In the end, I think itís apparent that these two markets will merge. This will leave standalone HTML editors like GNN Press, PageMill, and HotDog Pro in the dust. FrontPage and SiteMill will be relegated solely into web site management programs with hooks to Netscape Navigator Gold or Internet Explorer 4 for authoring. High-end word processors and desktop publishers will be relegated to construction of print material.

Before this happens, HTML must gain all the features available in current word processors. Despite reports to the contrary [], Figure 13 shows how one can incorporate all the collaboration features of modern word processors into HTML with iShare. The main advantage traditional word processors retain is the ability to perform version control on embedded data such as pictures. This, however, is a feature that needs to be added to HTML, and when done, would lend itself to versioning via the iShare protocol.

Then again, the file formats sported by word processors naturally do not lend themselves to the Web; or else, they would have become standard, especially during the stages of HTML 2.0. The main obstacles to their acceptance are their formats are proprietary, they are binary instead of text, and they are large. Obviously one could fix the first one by sending the format to a neutral standards body. The second is becoming moot as more and more authoring is done with GUI based tools. As seen in Figure 14, size is the killer problem.

|

Word Processor Feature |

Internet Equivalent |

|

Document Information (i.e. account number, contact information, client name, etc.) |

HTML META tag [] |

|

Comments |

DIV tag with a specific ID containing formatting information specific to an author. Embed a Java Applet that shows a tool-tip with the comment upon mouse-over. |

|

Fast Save Feature (appends changes to end of document to avoid re-writing clean document) |

iShare labels embedded into the master document. |

|

Version Control (saving multiple versions of a file into a single document) |

iShare labels embedded into the master document. |

|

Real time collaborative editing on a single document. |

Microsoft NetMeeting |

|

Access rights (i.e. Version management, editing control) |

Some of these are gained through the Group member extension to iShare. Otherís through HTTP 1.1. |

|

Version Control embedded data (i.e. pictures) |

N/A Ė HTML cannot embed such data. |

|

Routing features (send document to x, then y, then z, for successive approval) |

State information onto the signed optional extension in iShare labels or into META tags, and hooks from the UA to the mail client. |

|

Word 97 |

HTML w/iShare |

|||

|

V1 |

V2 |

V1 |

V2 |

|

|

Hello World |

11,776 |

26,112 |

134 |

134 + 274 = 408 |

The Network Computer (NC) is the name for the new breed of dumb terminals. These devices appear attractive since they promise to reduce total cost of ownership by easing the administration, maintenance, and continual replacement of computing devices. The most common proposal is for the NC to run new Java based applications that it fetches from application servers and stores output on external data servers. Although the press has attached itself to new $500 NC boxes, old DOS machines with a new Java Operating system will do just fine.

The main technical difference between NCs and standard personal computers (PC) stems from the distribution of load. Software and data for a PC is stored in its local hard disk. This information is stored in remote servers for NCs. Since this information is stored remotely, new issues concerning load distribution and client server interaction arise. One must pay more attention to network bandwidth and congestion.

iShare can operate in a mode that fits into the world of network computers. Authors using NCs can create and modify documents as normal. Instead of saving the document in a proprietary format, the HTML based word processor saves changes as an iShare label and sends this to the server for storage. Since the label is sent instead of the entire document, bandwidth is conserved. At the other end of the connection, the server stores this information in its database. The next time the document is requested, the server returns all the labels along the current branch. In its idle time, the server merges the versions into a single document, thus reducing the amount of information it returns to the client.

Revision Control Systems are software that ease the process of storing and recalling a document throughout its development. RCS first gained popularity among software developers to help archive and share their code. Since developers, even those on the same team, often use different editors, RCS are typically external command line tools. Modern RCS accommodate directory structures, binary files, hook into graphical front-ends, and are used by non-programmers.

The WEBDAV proposal aims to interface web clients and servers with traditional RCS backends. With this interface, people will be able to swap their old proprietary RCS backendís to ones that are iShare compatible. This will provide a dual interface for viewing the files, and a standardized front end for their storage.

Although the precise details of the backend storage facilities of common RCS are unimportant, a notable exception lies in the calculation of deltas. Some RCS store the most recent version of the document in full, then store deltas which are used to construct older versions. This eliminates construction time and minimizes the bandwidth when viewing the most recent version (the most common case).

The main problem with this scheme is that it requires the author to have write access to the original document store. This prohibits implementation of adversarial editing schemes. However, as previously noted, this is not a problem with Intranets. To use reverse deltas in iShare, one simply sets the direction flag in the mandatory extension. Information about the author (i.e. name, comment, signature, etc) is stored in the reverse iShare label (along with the base document, one should include an iShare label that reverts this to the NULL document).

A lesser problem with reverse deltas is that the author sends both the final document and the reverse iShare label to the server. If one does not sign the iShare label, and the server runs a special script, the author need only send a forward iShare label Ė the server can then construct the reverse iShare label and new final document.

The Usenet system is the most popular threaded message system in the world. People construct their message and send it to their Usenet server, which in turn forwards it to every other Usenet server. The result of this distribution is that every user has a loosely replicated view of the entire discussion on a server just a few hops away. Unfortunately only a small percentage of messages are actually read.

Storage ConsiderationsApart from the storage overhead that comes with the replication of Usenet messages across News servers and the duplication of cross-posted messages, storage of Usenet message is inefficient. A cursory examination of several messages shows the average message contains 14 text headers. While the functionality of some of these fields is duplicated by iShare fields (i.e. From, Subject, Date, Message-ID), others are useless artifacts of the system (i.e. Lines, Path, NNTP-Posting Host). While switching to iShare would reduce the size and number of these headers, the savings would be a small constant.

The storage problems of the Usenet are derived from the low signal to noise ratio (see Appendix D: Sample Usenet Post). Too many messages are one phrase replies like "I agree," "post the response to the entire group," or "Yeah, me." The problem is that these many of these posts include a carbon of the original message and attach a large signature. Simple message like these can be handled more efficiently with iShare by using a predefined comment flag. iShare news clients would intelligently display this information aside the original message with information like "number of people in agreement." Similarly, other voting systems could be introduced, as well as filters that use that data.

Another area primed for improvement is the attachment of binary files to News postings. Currently, these attachments are embedded into the mail message in an encoded format that usually expands the message by 33%. An HTML based iShare approach allows these files to remain in their original location in their native format.

The replication of Usenet messages came about at a time when the Internet backbone operated over a low bandwidth connection. This distribution conserved Internet bandwidth by caching the Usenet on local servers. While this increased the MTTF of the Usenet, the main benefit to users was that the messages are stored locally, thus reducing the latency and bandwidth to the characteristics of the local net.

Web users are demanding this speed up as well. The gateway machine between the Internet and corporate Intranets typically run caching Proxy servers. Quality ISPs run these as well. Backing up a step, Proxy servers and Usenet servers are similar beasts, each cache bits. There is no need for two disparate caching servers. If one were to convert the Usenet to an iShare based system, one could also convert News servers to general caching servers.

A second usage for the iShare system is to speed in the recovery and storage space associated with personal email. Imagine two people, Ben and Alyssa, that have an ongoing correspondence on the same topic. Instead of creating new messages, they keep replying to each other. By default, most users have the "include last email in reply" function turned on. Power users often find this setting and ax it to reduce transmission time. In exchange, they must now create a folder and archive each message if they wish to rebuild the conversation later.

Email clients can use iShare to reduce the bandwidth necessary to send and receive messages, and to ease the task of archiving a thread. Imagine the case where in their correspondence, both Ben and Alyssa simply create original text atop the last reply. The iShare annotation is simply one insertion at byte offset zero. It is sent through standard email as a new mime type (the plaintext message may be included as well for non-iShare mail clients). When downloaded, the email client decodes the iShare annotation and places it in a file with the other annotations on the same thread. A reference to this latest annotation appears in the recipientís inbox. To get rid of clutter, the email client includes a switch that allows the reader to toggle between a view with the index and the most recent message, or the entire thread.

A second use of iShare is to reduce server side storage associated with messages to large mailing lists. Suppose newbie@aol.com sends the "Good-Times Virus" warning to a mailing list consisting of 500 close friends. The AOL email server, recognizing that 499 of these recipients are also AOL members, the other a Prodigy member, wants to conserve bandwidth. The AOL email server packages this message into an iShare label, and fills the optional field with a new extension called "refcount." Each time one of newbieís friends downloads his email the mail server decrements the refcount and sends the decoded message. A new IMAP version of the mail server has even longer benefits from such a technique. Then again, this is a hack that can be applied to any mailing list message, regardless of iShare.

Microsoft Exchange, Lotus Notes, and Netscape Collabra boast a feature called Public Folders that is a marriage between the Usenet, email, and the Web[, ]. Public Folders are similar to the Usenet in that users are presented with a threaded view of the groupís conversation that is stored on remote servers. The messages can be searched, filtered, and even replicated to the local machine for offline viewing. Public Folders are similar to email in that people can post a single message to the "mailing list" and receive notification of new messages via their inbox. Finally, Public Folders are similar to the Internet solutions in that these systems can replicate content onto the Usenet, and support protocols like NNTP, SMTP, HTML and SSL.

This marriage between the Usenet and Email should result in the destruction of one of these messaging solutions. These proprietary products have shown that itís possible to integrate the privacy and security of email with the efficiency and convenience of remote storage and archival of messages. This trend is being advanced on with the email community with the IMAP protocol that provides remote manipulation of email boxes.

The main reason for using iShare as a foundation for this new message system is to simplify the process of message archival and offline reading. In most cases, the Public Folder administrator will set a timeout rate on the messages in the Public Folder. Examples of rules dictating this timeout rate are that messages are deleted in the order they were received after 500 have been accumulated, or messages are deleted when they are older than 14 days. This contrasts with the practice of permanent archival of all email messages one receives. By using iShare, one gets automatic reconciliation between locally archived messages and those stored on remote servers. This feature is further enhanced if the local client can gain access to the serverís expiration rules.

Obviously, there are many research projects related to version control and collaboration. While iShare learns from these projects, it is most closely influenced by the VTML system []. Without an explicit comparison, I assert that iShare is the simplest system that: satisfies the "Functional Requirements and Framework for Versioning on the WWW" Internet Draft [], coexists current protocols, and has an easy adoption pathway.

Legal issues raised by the inception of the iShare system are those of copyright infringement, spoofing, libel, and slander. For the most part, these are the same issues raised with the presence of standard web pages. Nonetheless, there are subtle differences, some of which can be minimized with an effective user interface.

CopyrightContent authors cry "copyright infringement" when unauthorized web sites makes use of their original content. These complaints arise when the unauthorized site copies the original content onto his server (i.e. plagiarism, scanned photographs, copied sound files), and even when they link data from the original site (i.e. an image located on the copyright holderís website). Of course, not all of these are Copyright violations, as some uses fall with the limits of the Fair Use clause of the Copyright Act [].

Nonetheless, content authors are pressing forward with legal action [] and companies dedicated to combing the Web finding such violations for their clients are appearing. One particular case of note is the use of frames. Frames allow authors to create a web page that is a collage of other web pages. This makes it difficult for users to determine the origin of the page.

iShare exacerbates this problem as authors can create pages completely interwoven with the parts of the original page. Gone are content divisions by means of horizontal or vertical lines. Gone too are any portions of the original page that might divulge its origin.

A second issue occurs when an administrator merges multiple annotations down to a single document. Is this simply a compilation of existing information? Or is this stealing? A related issue when authors merge annotations is that of hit counting. If the merged document is stored on a server other than that of the original version, the author of the original document has no way to count the number of times his page was hit, thus adversely affecting advertising revenue. This issue is similar to that faced by proxy server vendors, but has a more complex solution since there is no central server to report total hits at the end of the day.

A common way to steal information from a user is to impersonate someone they trust. An example of this is to construct a website that looks similar to

http://espnet.sportszone.com and alter information (i.e. the address to which people send their passwords / credit card number, or present incorrect sports scores / betting lines). After constructing this site or even a proxy site, the spoofer then needs to attract customers (this can be done through a number of techniques ranging from IP spoofing to registering a similarly spelled domain name). iShare makes spoofing easier since the spoofer needs to change a small amount of information (such as the submission URL for forms) and since valid connections are still made.

iShare also makes it easier to get away with libel and slander. By creating a simple annotation, one can write a phrase like "Captain Crunch likes soggy cereal." Worse yet, blame would be associated with the creator of the original page.

While impossible to stop authors from creating legally questionable derived work, programmers can add a content advisor to the UA that alerts users who view suspect pages. This content advisor can be set to either block derived pages completely, flash a user-interface indicator when the page is displayed.

Options for standard web content is the ability to warn users when either inline or framed material (i.e. pictures, video, sound, entire web pages) is located at a different IP address or domain names. This control can have finer granularity for iShare content, as one has the ability to judge access based upon editing groups.

Cryptography, in the form of digital signatures helps provide accountability when legal actions become necessary. Digital signatures are already employed by Authenticode on Active-X controls, and will soon appear for Java applets []. Additionally, both Netscape and Microsoft have signed deals with VeriSign to issue free certificates to Navigator [] and Internet Explorer [] users. The content advisor would also include a generic checkbox to disallow non-signed pages. This will only become more powerful as legislation that gives digital signatures the same legal status as manual signatures [] is passed.

The computer software industry is going through a process of convergence. Web Browsers are becoming the universal viewer. HTML is becoming the standard layout language and file format. HTTP is becoming the generic transport. Consequently, applications coded to proprietary standards are being replaced by ones based on Internet standards. For this transformation to be successful, the feature set of these new applications must be a superset of the old ones.

iShare is a new system that leverages existing standards to add version control and annotation support to HTML and other Internet addressable objects. In terms of version support and annotation capabilities, it fills the void between the capabilities of HTML based systems and that of legacy applications. It helps reduce the bandwidth and communication required for distributed editing. It enables a new type of annotations whereby one doesnít need write access to the original document. It gives a standard annotation format with informative meta information that can be used to make smart, standardized versioning indexes for all types of resources.

The iShare system is currently in version 1, and thus has some flaws. The next section identifies some hidden assumption and problems with the current system. The final section lists some areas and problems that should be addressed in future versions of this specification.

ResultsThe first assumption of the iShare system is that authors have write access to a globally readable server. This service is available today at a nominal cost through ISPs and is free in a companyís Intranet. The problem is that management of this remote storage is more difficult than that of local storage. Until there is a free infrastructure that eases the storage, discovery, and expiration of annotations, construction of adversarial annotations will be limited to power users. This will cease to be problematic as operating systems ship with integrated web servers and people remain connected all day or if the NC becomes popular.

A related problem but more serious problem is that of dead links. When using forward deltas, the method necessary for adversarial annotations, a broken link will render the future versions unusable. This break results from down servers, moved or deleted resources, or changes to a prior version. Although this problem is lessened by the ability to merge or archive past versions, the overall reliability of this iShare system is less than that of the either the Web or the Usenet.

iShare is an efficient system in terms of storage requirements. Versions can be stored as compressed deltas. This makes it cheap and quick for authors especially those on cellular links to compose new versions of a document. Additionally, this format reduces the storage space required on the disk. This reduction in disk space is just a pleasant side effect of the iShare protocol. I realize that hard drive space is an abundant quantity, and that it is not worth the effort to adopt iShare if this is a sole consideration.

This version of the iShare protocol addresses many issues involved with version control and collaboration across the Internet. While it is currently ready for Web wide usage, I can already see over the horizon issues that must be solved in the next version.

Editing GroupsThe first, and most important addition, will be to define the format for editing groups. Groups, as you remember, are a collection of editors whom you trust to create subsequent versions. In typical browsing mode, the UA will present the most recent version that was authored by someone in the original editing group. If the original document was written in HTML as opposed to an iShare label, the UA displays the most recent annotation embedded inside that HTML. The UA must give the viewer a cue when they display documents authored by people outside of this group.

Groups were omitted from the first version of the draft due to questions over the validity of this field. Obviously, the field should be a list of public keys that belong to members of this group. The matching private key is obviously used to sign the iShare label. The first problem is how to handle revocation of these keys. The second, a reference to a database for extended information on the key (i.e. the name of the owner of the key, date of expiration, etc.). The third problem is that of storage space. Keys are typically 512 bits, and sites have many authors. These factors indicate that the size of the base label could explode. We need to define a way to externally reference author information Ė true especially for sites where this is redundant across many pages.

The next improvement is to add a pattern matching scheme for the insertion of data. This allows one to make general modifications to pages of a constant structure, whose underlying data keeps changing. To handle this, one must drastically change the format of the version numbers, perhaps even to a scheme such as the one in nHighestNumber++, so long as authors realize its limitations.